Temple, London

The Temple refers to the area in the vicinity of Temple Church. It is one of the main legal districts in London and a notable centre for English law, both historically and in the present day. It consists of the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple, which are two of the four Inns of Court and act as local authorities in place of the City of London Corporation within their areas.

| Temple | |

|---|---|

Temple Church | |

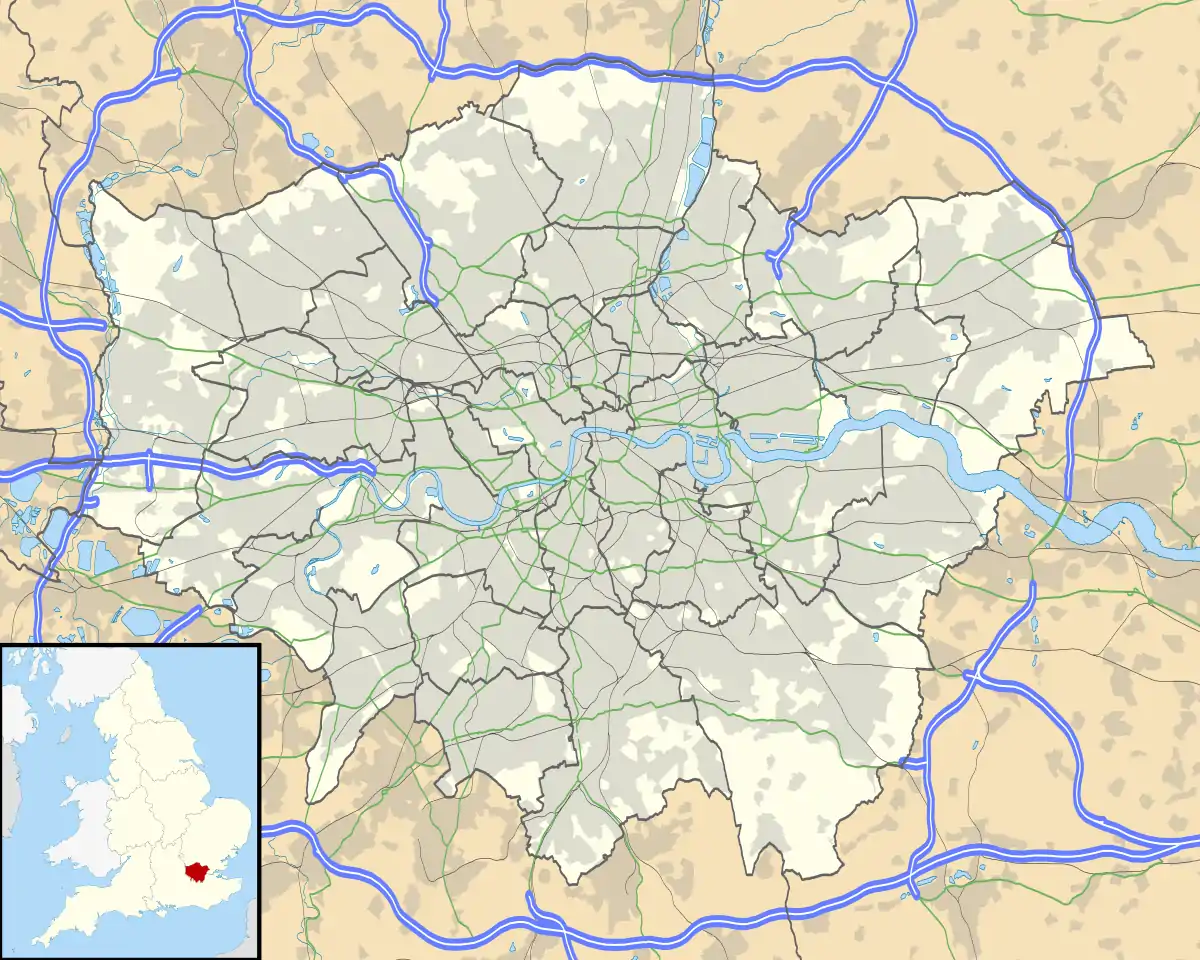

Temple Location within Greater London | |

| Sui generis | |

| Administrative area | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | EC4 |

| Postcode district | WC2 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | City of London |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

The Royal Courts of Justice are just to the north and Temple tube station is located to the west in the City of Westminster. The wider Temple area is roughly bounded by the River Thames (the Victoria Embankment) to the south, Surrey Street to the west, the Strand and Fleet Street to the north and Carmelite Street and Whitefriars Street to the east.

It contains many barristers' chambers and solicitors' offices, as well as some notable legal institutions such as the Employment Appeal Tribunal.[1] The International Institute for Strategic Studies has its headquarters at Arundel House.[2]

Toponymy

The name is recorded in the 12th century as Novum Templum, meaning 'New Temple'.[3] It is named after a 'new' church and related holdings once belonging to the Knights Templar. (The 'Old Temple' was located in Holborn, roughly where Lincoln's Inn now stands.[4]) The name is shared with Inner Temple, Middle Temple, Temple Church and the Temple Bar. After the Knights were suppressed, the area was divided into Inner Temple and Outer Temple (denoting what was within the City of London and what was without); while Inner Temple was later divided into Inner- and Middle-, Outer- generally fell into disuse.[3]

History

The Temple was originally the precinct of the Knights Templar whose Temple Church was named in honour of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. The Knights had two halls, whose modern successors are the Middle Temple Hall and the Inner Temple Hall. Only the Inner Temple Hall preserves elements of the medieval hall on the site, however (namely, the medieval buttery).

Upon the dissolution of the Knights Templar in 1312, the pope granted their possessions to the Knights Hospitaller. King Edward II ignored the claims of the Knights Hospitaller, and divided the Temple into the Inner Temple and the Outer Temple, being the parts of the Temple within and without the boundaries of the City of London respectively. Not until 1324, after the prior, Thomas L'Archer, paid a substantial bribe, was the claim of the Knights Hospitaller to the Inner Temple officially recognised in England; but even then Edward II still bestowed it on his favourite, Hugh le Despencer, in spite of the Knights' rights. On Hugh's death in 1326 the Inner Temple passed first to the mayor of London and then in 1333 to one William de Langford, the King's clerk, for a ten-year lease.[5]

In 1337 the Knights petitioned the king, now Edward III, to rectify the grant of consecrated land to a layman. As a result, the Inner Temple was divided between the consecrated land to the east and the unconsecrated land in the west, the eastern part continuing to be called Inner Temple and the western part becoming known as Middle Temple. Langford continued to hold Middle Temple at a reduced rent. In 1346, Langford's lease having by then expired, the Knights Hospitaller leased both Middle and Inner Temples to lawyers from St George's Inn and Thavie's Inn respectively.[6] However lawyers had already occupied the Temple since 1320, when it belonged to the Earl of Lancaster.[7]

When the Knights Hospitaller were dissolved by Henry VIII in the Reformation, the barristers remained as tenants of the Crown, for an annual rent of £10 for each society (of Inner and Middle Temple). Their current tenure dates from a charter granted to them by James I in 1608. Originally a grant of fee farm, the reversion was purchased from Charles II, finally giving the lawyers absolute title.[8] (In 2008 the 400th anniversary of the charter of James I was celebrated by Elizabeth II issuing new letters patent confirming the original grant.[9])

The Outer Temple area was granted to the Bishop of Exeter, and eventually purchased by the Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux, who gave his name to Essex Street and Devereux Court, as well as Essex Court in Middle Temple.[10]

The area of the Temple was increased when the River Thames was embanked by the Victoria Embankment, releasing land to the south which previously lay within the tidal reaches of the river. The original bank of the river can clearly be seen in a drop in ground level, for example in the Inner Temple Gardens or the stairs at the bottom of Essex Street.

The area suffered much damage due to enemy air raids in World War II and many of the buildings, especially in the Inner Temple and Middle Temple inns, had to be rebuilt. Temple Church itself was also badly damaged and had to be rebuilt. Nonetheless the Temple is rich with Grade I listed buildings.

Inner Temple and Middle Temple

The core of the district lies in the City of London and consists of two Inns of Court: Inner Temple (eastern part) and Middle Temple (western part). The Temple Church is roughly central to these two inns and is governed by both of them.

The Inns each have their own gardens, dining halls, libraries and administrative offices, all located in their part of the Temple. Most of the land is, however, taken up by buildings in which barristers practise from sets of rooms known as chambers.

There was a long-running dispute between the two inns concerning which one was the older and which ought to have precedence over the other accordingly. This was resolved in 1620 when a tribunal of four judges resolved that all four inns should be equal, "no one having right to precedence before the other."[11]

Until the twentieth century, many of the chambers in the Temple were also residential accommodation for barristers; however, shortage of space for professional purposes gradually limited the number of residential sets to the very top floors, which are largely occupied by senior barristers and judges, many of whom use them as pied-à-terres, having their family home outside London. (There are also a limited number of rooms reserved for new barristers undertaking the Bar Professional Training Course.) This, coupled with a general move of population out of the City of London, has made the Temple much quieter outside working hours than it appears, for example, in the novels of Charles Dickens, which frequently allude to the Temple. Today, approximately a quarter of the chambers buildings in the Inner Temple and Middle Temple include residential accommodation, and current planning policy is to retain this where possible, to retain the special "collegiate" character of the Temple Inns of Court.[12]

There is also a 19th-century building called "The Outer Temple", situated between Essex Court and Strand, just outside the Middle Temple boundary in the City of Westminster, but this is not part of the modern Inns of Court, has commercial landowners and is not directly related to the historic and long-defunct Outer Temple inn.

An area known as Serjeant's Inn was formerly outside the Temple, although at one time also occupied by lawyers (the Serjeants-at-Law). In 2001 it was acquired by the Inner Temple (it is adjacent and connected to King's Bench Walk in the Inner Temple) with a view to converting it into barristers' chambers. However it was instead converted into a hotel.

Liberty

Inner Temple and Middle Temple are two of the few remaining liberties, an old name for a geographic division. They are independent extra-parochial areas, historically not governed by the City of London Corporation[13] and are equally outside the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Bishop of London. They are today regarded as local authorities for most purposes,[14] but can delegate functions to the Common Council of the City of London, as provided in the Temples Order 1971.[14] They geographically fall within the boundaries and liberties of the City of London, but can be thought of as independent enclaves. They both are part of the City ward of Farringdon Without. The Parliamentary Boundaries Act 1832 included The Temple within City of London parliamentary constituency.[15]

The southern boundary of the Temple liberties was the natural bank of the River Thames until the Victoria Embankment was constructed (1865–1870). The boundary of the Temple liberties remained fixed despite this notable engineering work, which meant that the Inner and Middle Temple lost their frontage to the Thames replacing that amenity chiefly with gardens. (The boundaries of the Inner and Middle Temple liberties have not changed in centuries, although both now own properties just beyond their liberties' boundary.) The Victoria Embankment (which is a major thoroughfare with an Underground line running beneath) does not therefore form part of the Inner or Middle Temple – the southern boundary today runs along the boundary fence where the Temple gardens meets the Victoria Embankment road, more or less where the original bank of the Thames used to be. The City of London's southern boundary on the other hand runs along the centre of the Thames itself.

Temple Church

The Temple Church is a Royal Peculiar.[16] It was built by the Knights Templar and consecrated in 1185. It is jointly owned by the Middle Temple and Inner Temple inns.

Temple tube station and pier

Temple gives its name to Temple tube station, served by the District (green) and Circle (yellow) lines, which is situated in the southwest of the area, between Temple Place and the Victoria Embankment. There is also a Temple Pier on the Victoria Embankment, situated near the Tube station immediately upstream of the Westminster-City of London boundary; HQS Wellington is permanently moored there.

See also

General:

Further reading

- Bellot, Hugh H.L. (1902). The Inner and Middle Temple: Legal, Literary and Historical Associations. London: Methuen & Co.

References

- "Contact Us". Employment Appeal Tribunal.

- "How to Find Us". International Institute for Strategic Studies.

- Anthony David Mills (2001). Oxford Dictionary of London Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280106-6.

- Bellot 1902, p. 7

- Bellot 1902, pp. 19–24.

- Bellot 1902, pp. 20–25.

- Bellot 1902, p. 20.

- Bellot 1902, p. 25.

- "Royalty and the Inn'" Middle Temple website, June 2017 (retrieved 12 November 2017).

- Bellot 1902, pp. 19–20.

- Bellot 1902, pp. 268–269.

- "Housing study area profile 10: Temples" (PDF). City of London Corporation, Department of the Built Environment. 31 March 2015. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2016.

- City of London (Approved Premises for Marriage) Act 1996, 1996, c. iv, Preamble

- "The Inn as a Local Authority". The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple.

- "2 & 3 Will. 4 c. 64 Schedule O 22". The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 & 3 William IV. London: His Majesty's Statute and Law Printers. 1832. p. 351. Retrieved 2 August 2019.; Commissioners on Proposed Division of Counties and Boundaries of Boroughs (20 January 1832). "City of London". Parliamentary Representation: Further Return to an Address to His Majesty, Dated 12 December, 1831; for Copies of Instructions Given by the Secretary of State for the Home Department with Reference to Parliamentary Representation; Likewise Copies of Letters of Reports Received by the Secretary of State for the Home Department in Answer to Such Instructions. Reports from Commissioners on Proposed Division of Counties and Boundaries of Boroughs. Volume II Part I. Parliamentary Papers. 1831–32 HC 39 (141) 1. p. 117. Retrieved 2 August 2019.; also Metropolitan Boroughs Map included with the report.

- Inner Temple Library website (retrieved 10 August 2018)

External links

![]() Media related to Temple, London at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Temple, London at Wikimedia Commons