Temple of Caesar

The Temple of Caesar or Temple of Divus Iulius (Latin: Templum Divi Iuli; Italian: Tempio del Divo Giulio), also known as Temple of the Deified Julius Caesar, delubrum, heroon or Temple of the Comet Star,[1] is an ancient structure in the Roman Forum of Rome, Italy, located near the Regia and the Temple of Vesta.

| Temple of Divus Iulius | |

|---|---|

Plan of the Temple of Divus Iulius | |

| Location | Regione VIII Forum Romanum |

| Built in | Inauguration 18 August 29 BC |

| Built by/for | Emperor Augustus |

| Type of structure | Temple with, probably, a podium rostra in the frontal part |

| Related | Julius Caesar, Assassination of Julius Caesar, Pontifex Maximus, Emperor Augustus |

Temple of Divus Iulius | |

History

The temple was begun by Augustus in 42 BC after the senate deified Julius Caesar posthumously. Augustus dedicated the prostyle temple (it is still unknown whether its order was Ionic, Corinthian or composite) to Caesar, his adoptive father, on 18 August 29 BC, after the Battle of Actium. It stands on the east side of the main square of the Roman Forum, between the Regia, Temple of Castor and Pollux, and the Basilica Aemilia, on the site of Caesar's cremation and where Caesar's testament was read aloud at the funeral by Mark Antony.

Caesar was the first resident of Rome to be deified and so honored with a temple.[2] A fourth flamen maior was dedicated to him after 44 BC, and Mark Antony was the first to serve as Flamen Divi Julii, priest of the cult of Caesar.

The high platform on which the temple was built served as a rostra (Rostra ad divi Iuli) and, like the rostra at the opposite end of the Forum, was decorated with the beaks of ships taken at the battle of Actium.

The Temple of Caesar was the only temple to be entirely dedicated to the cult of a comet (referred to as a 'comet star')[1] The comet, appearing some time after Caesar's murder (44 BC), was considered to be the soul of the deified Julius Caesar and the symbol of the "new birth" of Augustus as a unique Roman ruler and Emperor.[3] In Greek and Roman culture, comet is an adjective describing the distinctive characteristic of a special star. "Comet star" means "long-haired star", and it was so represented on coins and monuments. Here is an excerpt of an account by Pliny, with parts of a public speech delivered by Augustus about the comet, his father Caesar,[4] and his own destiny:

The only place in the whole world where a comet is the object of worship is a temple at Rome. ... His late Majesty Augustus had deemed this comet very propitious to himself; as it had appeared not ... long after the decease of his father Caesar. ... People believed that this star signified the soul of Caesar received among the spirits of the immortal gods.[1]

The "Divine Star" was represented on coins, and probably worshiped in the temple itself either as a "comet star" or as a "simple star". The simple star had been used as a general symbol of divinity since 44 BC, as can be seen on the 44 BC coin series; after the appearance of the comet, the simple star was transformed into a comet by adding a tail to one of the rays of the simple star, as is shown on the 37–34 BC, 19–18 BC and 17 BC coin series.

According to Appian[5] the place near the Regia and probably part of the main square of the Roman Forum was a second choice, because the first intention of the Roman people was to bury Caesar on the Capitoline Hill among the other Gods of Rome. However, the Roman priests prevented them from doing so (allegedly because the cremation was considered unsafe due to the many wooden structures there) and the corpse of Caesar was carried back to the Forum near the Regia, which had been the personal headquarters of Caesar as Pontifex Maximus. After a violent quarrel about the funeral pyre and the final destiny of Caesar's ashes, the Roman people, the men of Caesar's party, and the men of Caesar's family decided to build the pyre at that location. It seems that in that very place there was a tribunal praetoris sub divo with gradus known as the tribunal Aurelium, a structure built by C. Aurelius Cotta around 80 BC near the so-called Puteal Libonis, a bidental used for sacred oaths before trials.[6] After the funeral of Caesar and the building of the temple, this tribunal was then moved in front of the Temple of Caesar, probably to the location of the so-called Rostra Diocletiani.

Caesar's corpse was carried to the Roman Forum on an ivory couch and set up on the Rostra in a gilded shrine modelled on the Temple of Venus Genetrix, the goddess from whom the family of the Iulii claimed to have originated. Mark Antony delivered his famous speech followed by a public reading of Caesar's will, while a mechanical device, positioned above the bier itself, rotated a wax image of Caesar so that people were able to clearly see the 23 wounds in all parts of the body and on the face. The crowd, moved by the words of Mark Antony, Caesar's will, and the sight of the wax image, attempted but failed to carry the corpse to the Capitol to rest among the gods. In the end the corpse was placed on a funeral pile created near the Regia by making use of any wooden objects available in the Forum, such as wooden benches, and a great cremation fire lasted all the night long. It seems that an ordinary funeral had been prepared for Caesar at the Campus Martius.

An altar and a column were briefly erected at the cremation site for the cult of the murdered pontifex maximus, a sacred man, against whom it was strictly prohibited to use cutting weapons and objects. The column was of Numidian yellow stone and had the inscription Parenti Patriae, i.e., to the founder of the nation. But this first monument was almost immediately taken down and removed by the anti-Caesarian party. In 42 BC Octavian, Lepidus and Mark Antony decreed the building of a temple to Caesar.

Some time after the death of Caesar a comet appeared in the sky of Rome and remained clearly visible every day for seven days, starting one hour before sunset. This comet appeared for the first time during the ritual games in front of the Temple of Venus Genetrix, the supposed ancestor of the Julii family in the Forum of Julius Caesar, and many in Rome thought it was the soul of deified Caesar called to join the other gods. After the appearance of this sign, Augustus delivered a public speech giving an explanation of the appearance of the comet. The speech is partially known since a partial transcription by Pliny the Elder has been handed down. After the public speech Augustus caused a few series of coins devoted to the comet star and to the deified Caesar, "Divus Iulius", to be struck and widely distributed, so it is possible to have an idea of the representation of the comet star of the deified Julius Caesar.

During his public speech about the appearance of the comet, Augustus specified that he himself, the new ruler of the world, was born politically at the very time his father Julius Caesar appeared as a comet in the sky of Rome. His father was announcing the political birth of his adoptive son; he was the one born under the comet and whom the appearance of the comet was announcing. Other messianic prophecies about Augustus are related by Suetonius, including the story of the massacre of the innocents conceived in order to kill the young Octavius soon after his own birth. Augustus wanted to be considered the real subject of any kind of Messianic prophecies and accounts. Later during his reign, he ordered that all other books of prophecies and Messianic accounts be gathered and destroyed. The temple therefore ended up as representing both Julius Caesar as a deified being and Augustus himself as the newborn under the comet. The comet star itself was an object of public worship.

The consecration of the temple lasted many days, during which there were reconstructions of the siege of Troy, gladiatorial games, hunting scenes, and banquets. On this occasion a hippopotamus and a rhinoceros were displayed in Rome for the first time. It seems that the doors of the Temple were left opened so that it was possible to see the statue of the deified pontifex maximus Julius Caesar from the main square of the Roman Forum. If this is true, the new interpretation about the location of the Rostra Diocletiani and Rostra ad Divi Iuli cannot be correct.

Augustus used to dedicate the spoils of war in this temple.[7] The altar and the shrine conferred the right of asylum.[8] Every four years a festival was held in front of the Rostra ad Divi Iuli in honour of Augustus.[8] The Rostra were used to deliver funeral speeches by succeeding emperors. Drusus and Tiberius delivered a double speech in the Forum; Drusus read his speech from the Rostra Augusti and Tiberius read his from the Rostra ad Divi Iuli, one in front of the other. The emperor Hadrian delivered what was perhaps a funeral speech from the Rostra ad Divi Iuli in 125 AD, as can be seen on the coin series struck for the occasion.

Architecture

The temple remained largely intact until the late 15th century, when its marble and stones were reused to construct new churches and palaces. Only parts of the cement core of the platform have been preserved.

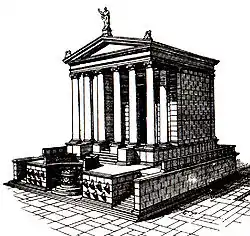

The plan of this temple is missing in the Imperial Forma Urbis. The remaining fragments for this area of the Roman Forum are on slabs V-11, VII-11, VI-6[9] and show plans of the Regia, the Temple of Castor and Pollux, the Fons and Lacus Iuturnae, the Basilica Iulia and the Basilica Aemilia. Vitruvius[10] wrote that the temple was an example of a pycnostyle front porch, with six closely spaced columns on the front. However, the arrangement of the columns is uncertain, as it could be either prostyle[11] or peripteral.[12]

The column order originally used for this temple is uncertain. Ancient coins with representations of the Temple of Divus Iulius suggest the columns were either Ionic or composite, but fragments of Corinthian pilastre capitals have been found on the site by archaeologists. Some scholars hypothesize that the temple had an Ionic pronaos combined with Corinthian pilasters on the cella walls, i.e., at the corners of the cella; other scholars consider the temple to have been entirely Corinthian and the coin evidence as bad representations of Corinthian columns. The distinction between Corinthian and composite columns is a Renaissance one and not an Ancient Roman one. In Ancient Rome Corinthian and composite were part of the same order. It seems that the composite style was common on civil buildings and Triumphal arch exteriors and less common on temple exteriors. Many temples and religious buildings of the Augustan Age were Corinthian, such as the Temple of Mars Ultor, the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, and others.[13][14][15][16]

The temple was destroyed by fire during the reign of Septimius Severus and then restored. Comparisons with coins from the times of Augustus and Hadrian suggest the possibility that the order of the temple was changed during the restoration by Septimius Severus. The entablature and the cornice found on the site have a modillions and roses structure typical of the Corinthian order.

The original position of the staircase of the podium remains uncertain. It may have been at the front and sides of the podium,[17] or at the rear and sides of the podium .[18] The position at the rear is a reconstruction model based on a hypothesized similarity between this temple and the Temple of Venus Genetrix in the Forum of Caesar. This similarity is not proved and merely based on the fact that during the public funeral and Mark Antony's speech the body of Julius Caesar was set on an ivory couch and in a gilded shrine modelled on the Temple of Venus Genetrix. The front position is based on some evidence from 19th century excavations and on an overall impression of the actual site, and on the depictions on ancient coins.

Rostra

Dio Cassius reports the attachment of a rostra from the battle of Actium to the podium. The so-called Rostra ad Divi Iuli was a podium used by orators for official and civil speeches and especially for Imperial funeral orations. The podium is clearly visible on coins from the Hadrian period and in the Anaglypha Traiani, but the connection between the rostra podium and the temple structure is not evident.

Also in this case there are many different hypothetical reconstructions of the general arrangement of the buildings of this part of the Roman Forum. According to one, the Rostra podium was attached to the Temple of Divus Iulius and is actually the podium of the Temple of Divus Iulius with the rostra (the prow of a warship) attached in a frontal position.[19] According to other reconstructions, the Rostra podium was a separate platform built west of the temple of Divus Iulius and directly in front of it, so the podium of the Temple of Divus Iulius is not the platform used by the orators for their speeches and not the platform used to attach the prows of ships taken at Actium. This separate and independent podium or platform, known as Rostra ad Divi Iuli, is also called Rostra Diocletiani, due to the final arrangement of the building.[20]

Upper decoration of the frontal pediment

From an analysis of ancient coins it is possible to determine two different series of decorations for the upper part of the frontal pediment of the temple. Fire tongues (their identification is uncertain) decorated the pediment, as in Etruscan decorated antefixes, similar to the decoration of the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill. The fire tongues perhaps recalled the flames of the comet (star) on Augustan period coins. With a star as the main decoration of the tympanum, as can be seen on the Augustan coins, the whole temple had the function to represent the comet (star) that announced the deification of Julius Caesar and the reign of Augustus, as reported by Pliny the Elder.

A statue at the vertex of the frontal pediment and two statues at the end corners of the pediment, the classical decoration for the pediments of the Roman temples, date to Hadrian's reign.

Other Augustan era buildings with that particular type of Etruscan-style decoration appear on coins, as well as on representation of the frontal section of the Curia.

The niche and the altar

The niche and the altar in front of the temple podium are also a problem of interpretation based on scarce data. They were visible in 29 BC when the temple was dedicated and when Augustus' coin series with the temple of Divus Iulius was struck from 37 BC to 34 BC. For the period after the coinage of that series there is no clear evidence. It is known that at some time the altar was removed and the niche filled in and closed with stones to create a continuous wall at the podium of the temple. According to various hypotheses this was done either in 14 BC,[21] or probably before the 4th century AD,[22] or after Constantine I or Theodosius I, due to religious concerns about the pagan cult of the emperor.[17]

Richardson and other scholars hypothesize that the filled in niche may have not been the altar of Julius Caesar, but the Puteal Libonis, the old bidental used during trials at the Tribunal Aurelium for public oaths. According to C. Hülsen the circular structure visible under the Arch of Augustus is not the Puteal Libonis, and other circular elements covered in travertine near the Temple of Caesar and the Arcus Augusti are too recent to belong to the Augustan era.

Measurements

The temple measured 26.97 metres (88.5 ft) in width and 30 metres (98 ft) in length, corresponding to 91 by 102 Roman feet. The podium or platform area was at least 5.5 m high (18 Roman feet) but only 3.5 m at the front. The columns, if Corinthian, were probably 11.8 to 12.4 m high, corresponding to 40 or 42 Roman feet.

Materials

- Tuff (inner parts of the building)

- Opus caementicium (inner parts of the building)

- Travertine (walls of the podium and the cella)

- Marble (podium revetement, columns, entablature and pediment of the temple; probably marble from Luni, i.e., Carrara marble)

Decoration and position of the remains

The frieze was a repetitive scroll pattern with female heads, gorgons and winged figures. The tympanum, at least during the first years, probably showed a colossal star, as can be seen on the Augustan coins.

The cornice had dentils and beam type modillions (one of the first examples ever in Roman temple architecture) and undersides decorated with narrow rectangular panels carrying flowers, roses, disks, laurel crowns and pine-cones. Remnants of the decorations, including elements of a Victory representation and floral ornaments, are visible on site or in the Forum Museum (Antiquarium Forense).

Interior

Augustus used the temple to dedicate offerings of the spoils of war. It contained a colossal statue of Julius Caesar, veiled as Pontifex Maximus, with a star on his head and bearing the lituus augural staff in his right hand. When the doors of the temple were left open, it was possible to see the statue from the Roman Forum's main square. In the cella of the temple there was a famous painting by Apelles of Venus Anadyomene. During the reign of Nero Apelles' painting deteriorated and could not be restored, so the emperor substituted for it another one by Dorotheus. There is also another painting by Apelles, depicting the Dioscuri with Victoria.

See also

References

- Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 2.93–94

- The existing Temple of Romulus near the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina is dedicated not to the founder of Rome, but to a deified son of the emperor Maxentius

- Cf. Star of Bethlehem

- Augustus was legally adopted by Caesar in 44 BC

- The Civil Wars, II, 148

- Mario Torelli, Typology and structure of Roman Historical reliefs

- Monumentum Ancyranum: Res Gestae

- Dio Cassius

- Stanford University #17, #18a, #18bc, #18d, #18e, #18fg, #19

- De Architectura, 3.3.2

- C. Hülsen, Bretschneider und Regenberg, 1904; J. W. Stamper, Cambridge University Press, 2005; B. Frischer, D. Favro and D. Abernathy, University of California Los Angeles, 2005

- Oxford Archaeological Guide; based on Hadrian coins from 125–128 AD

- C. Hülsen, Bretschneider und Regenberg, 1904

- J. W. Stamper, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- B. Frischer, D. Favro and D. Abernathy, University of California Los Angeles, 2005

- C.F. Giuliani, P. Verduchi, L'Area Centrale del Foro Romano. Florence 1987

- C. Hülsen, Bretschneider und Regenberg, 1904

- J. W. Stamper, Cambridge University Press, 2005; B. Frischer, D. Favro and D. Abernathy, University of California Los Angeles, 2005; Oxford Archaeological Guide

- C. Hülsen, Bretschneider und Regenberg, 1904)

- J. W. Stamper, Cambridge University Press, 2005; B. Frischer, D. Favro and D. Abernathy, University of California Los Angeles, 2005

- J. W. Stamper, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- Oxford Archaeological Guide

Further reading

- Claridge, Amanda. 2010. Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. 2nd ed., revised and expanded. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gorski, Gilbert, and James E. Packer. 2015. The Roman Forum: A Reconstruction and Architectural Guide. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Koortbojian, Michael. 2008. “The Double Identity of Roman Portrait Statues: Costumes and their Symbolism at Rome.” In Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture, Edited by Jonathan C. Edmondson and Alison M. Keith. Phoenix. Supplementary Volume; 46, 71-93. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Phillips, Darryl Alexander. 2011. “The Temple of Divus Iulius and the Restoration of Legislative Assemblies under Augustus.” Phoenix 65.3-4: 371-388.

- Wardle, David. 2002. “« Deus » or « divus » : The Genesis of Roman Terminology for Deified Emperors and a Philosopher's Contribution.” In Philosophy and Power in the Graeco-Roman World: Essays in honour of Miriam Griffin, Edited by Clark, Gillian and Rajak, Tessa, 181-191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

| Library resources about Temple of Caesar |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Iulius Caesar (Rome). |

- Temple of Caesar (General Description and Photo Gallery)

- UCLA Digital Roman Forum page for the "Iulius Divus, Aedes" Archaeological discussion and 3D reconstruction

- UCLA Digital Roman Forum page for the "Rostra Diocletiani" i.e. "Rostra ad Divi Iuli" Archaeological discussion and 3D reconstruction

- Stanford University Forma Urbis Romae: slabs of the Forum Area with Temple of Divus Iulius (the Temple of Divus Iulius is a missing part visible only as a simple plan out of the slabs)

- Temple of Caesar at digitales Forum Romanum by Humboldt University of Berlin

- Situated simulation of the Temple of Caesar for mobile phones and tablets