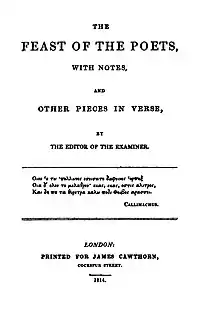

The Feast of the Poets

The Feast of the Poets is a poem by Leigh Hunt that was originally published in 1811 in the Reflector. It was published in an expanded form in 1814, and revised and expanded throughout his life (see 1811 in poetry, 1814 in poetry). The work describes Hunt's contemporary poets, and either praises or mocks them by allowing only the best to dine with Apollo. The work also provided commentary on William Wordsworth and Romantic poetry. Critics praised or attacked the work on the basis of their sympathies towards Hunt's political views.

Background

In 1811, Hunt began a magazine called the Reflector, which carried poetry and other literature. One of the works that he submitted was The Feast of the Poets. The work was intended as an update of the 17th century tradition of "Sessions of the Poets", a satirical portrayal of contemporary poets both good and bad. In 1813, James Cawthorn, a publisher, asked Hunt to complete a full length edition of the poem that would include both an introduction and notes to the work. Hunt began to work on the poem and the work was soon expanded.[1]

In January 1814, the work was published and well received by Hunt's friends. The new edition was dedicated to Thomas Mitchell and it ended with a sonnet that was dedicated to Thomas Barnes, both friends of Hunt.[2] The poem would be revised throughout Hunt's life, including an edition in 1815.[3]

Poem

The poem satirically describes many of Hunt's contemporaries: Wordsworth is experiencing a "second childhood", Coleridge "muddles" in writing, and William Gifford is a "sour little gentleman".[4] Four great poets, Thomas Moore, Walter Scott, Robert Southey, and Thomas Campbell are allowed to dine with Apollo while Samuel Rogers is only allowed to have tea.[5]

In the rewrite, Hunt says that was not included because "I haven't the brains".[6] His view of Wordsworth changed to praising Wordsworth as a great poet but also one that "substitute[s] one set of diseased perceptions for another:

he says to us, "Your complexion is diseased your blood fevered you endeavour to keep up your pleasurable sensations by stimulants too violent to last, which must be succeeded by others of still greater violence:- this will not do: your mind wants air and exercise, – fresh thoughts and natural excitements:- up, my friend; come out with me among the beauties of nature and the simplicities of life, and feel the breath of heaven about you". – No advice can be better: we feel the call instinctively; we get up, accompany the poet into his walks, and acknowledge them to be the best and the most beautiful; but what do we meet there? Idiot boys, Mad Mothers, Wandering Jews...[7]

Regardless of the problems, Hunt admits to a connection with Wordsworth, especially in their use of poetry to deal with complex psychological issues.[8]

Themes

The purpose of the notes was to describe, in Hunt's view, what would happen to the reputation of various poets. He placed a particular emphasis on the British Romantic poetry, including Lyrical Ballads, that sought to overcome the standards of neoclassical poetry with emphasis on the problems inherent in the French standards created by those like Nicholas Despreaux-Boileau. As such, Hunt praises Wordsworth as the leader of a new type of poetry.[9] Although Byron is not fully discussed in early editions of the poem, he is discussed in the notes as an individual who would become an important person who had already "taken his place, beyond a doubt, in the list of English Poets".[10] By the 1815 edition, Byron was introduced and was praised by Apollo, which reflected a friendship between the two.[11]

The work influenced how critics viewed Romantic poetry. Hunt's interpretation of Wordsworth and Wordsworth's poetry was later picked up and developed by William Hazlitt in a review of Wordsworth's Excursion. Hazlitt emphasised the egotistical aspects of Wordsworth's regular contemplation in his works. Hazlitt also relied on Hunt's criticism of Wordsworth preferring common people as his heroes. Hazlitt's review, grounded in Hunt's ideas, influenced John Keats's view of the "wordsworthian or egotistical sublime". Coleridge, in Biographia Literaria, relied on Hunt's claim that Wordsworth focused on the morbid aspects of life or dwelled too much on abstract concepts.[12]

Critical response

Hunt received favourable responses from many of his friends and from Byron and Byron's friend Thomas Moore. However, the magazines were divided on the basis of their political views as they matched with Hunt's own. Many claimed that Hunt's poem was seditious, including the British Critic, New Monthly Magazine and The Satirist. To the contrary, the Champion, with a review by John Scott, along with the Eclectic and the Monthly Review, praised the work. The Critical Review believed that Hunt should have stressed society when discussing Wordsworth's poetry.[13]

Notes

- Roe 2005 pp. 125–126, 201

- Roe 2005 p. 203

- Holden 2005 pp. 53, 79

- Roe 2005 p. 126

- Holden 2005 p. 85

- Roe 2005 p. 126

- Roe 2009 qtd. pp. 202–203

- Roe 2009 p. 203

- Roe 2005 pp. 201–202

- Roe 2005 qtd p. 202

- Holden 2005 p. 79

- Roe 2009 pp. 212–213

- Roe 2009 pp. 203–204

References

- Blainey, Ann. Immortal Boy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985.

- Blunden, Edmund. Leigh Hunt and His Circle. London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1930.

- Edgecombe, Rodney. Leigh Hunt and the Poetry of Fancy. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1994.

- Holden, Anthony. The Wit in the Dungeon. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2005.

- Roe, Nicholas. Fiery Heart. London: Pimlico, 2005.