The Lotos-Eaters

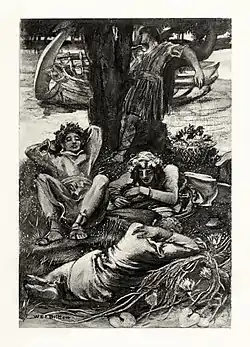

"The Lotos-Eaters" is a poem by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, published in Tennyson's 1832 poetry collection. It was inspired by his trip to Spain with his close friend Arthur Hallam, where they visited the Pyrenees mountains. The poem describes a group of mariners who, upon eating the lotos, are put into an altered state and isolated from the outside world. The title and concept derives from the lotus-eaters in Greek mythology.

Background

In the summer of 1829, Tennyson and Arthur Hallam made a trek into conflict-torn northern Spain. The scenery and experience influenced a few of his poems, including Oenone, The Lotos-Eaters and "Mariana in the South".[1]

These three poems, and some others, were later revised for Tennyson's 1842 collection.[2] In this revision Tennyson takes the opportunity to rewrite a section of The Lotos Eaters by inserting a new stanza before the final stanza. The new stanza describes how someone may have the feelings of wholeness even when there is great loss. It is alleged by some that the stanza refers to the sense of loss felt by Tennyson upon the death of Hallam in 1833.[3]

Poem

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The mariners are put into an altered state when they eat the lotos. During this time, they are isolated from the world:[4]

- Branches they bore of that enchanted stem,

- Laden with flower and fruit, whereof they gave

- To each, but whoso did receive of them

- And taste, to him the gushing of the wave

- Far far away did seem to mourn and rave

- On alien shores; and if his fellow spake,

- His voice was thin, as voices from the grave;

- And deep-asleep he seem’d, yet all awake,

- And music in his ears his beating heart did make. (lines 28–36)

The mariners explain that they want to leave reality and their worldly cares:[4]

- Why are we weigh’d upon with heaviness,

- And utterly consumed with sharp distress,

- While all things else have rest from weariness?

- All things have rest: why should we toil alone,

- We only toil, who are the first of things,

- And make perpetual moan,

- Still from one sorrow to another thrown;

- Nor ever fold our wings,

- And cease from wanderings,

- Nor steep our brows in slumber’s holy balm;

- Nor harken what the inner spirit sings,

- 'There is no joy but calm!"—

- Why should we only toil, the roof and crown of things? (lines 57–69)

The mariners demonstrate that they realise what actions they are committing and the potential results that will follow, but they believe that their destruction will bring about peace:[5]

- Let us alone. Time driveth onward fast,

- And in a little while our lips are dumb.

- Let us alone. What is it that will last?

- All things are taken from us, and become

- Portions and parcels of the dreadful past.

- Let us alone. What pleasure can we have

- To war with evil? Is there any peace

- In ever climbing up the climbing wave?

- All things have rest, and ripen toward the grave

- In silence—ripen, fall, and cease:

- Give us long rest or death, dark death, or dreamful ease. (lines 88–98)

Although the mariners are isolated from the world, they are connected in that they act in unison. This relationship continues until the very end when the narrator describes their brotherhood as they abandon the world:[6]

- Let us swear an oath, and keep it with an equal mind,

- In the hollow Lotos-land to live and lie reclined

- On the hills like Gods together, careless of mankind.

- For they lie beside their nectar, and the bolts are hurl’d

- Far below them in the valleys, and the clouds are lightly curl’d

- Round their golden houses, girdled with the gleaming world;

- Where they smile in secret, looking over wasted lands,

- Blight and famine, plague and earthquake, roaring deeps and fiery sands,

- Clanging fights, and flaming towns, and sinking ships, and praying hands.

- But they smile, they find a music centred in a doleful song

- Steaming up, a lamentation and an ancient tale of wrong,

- Like a tale of little meaning tho’ the words are strong;

- Chanted from an ill-used race of men that cleave the soil,

- Sow the seed, and reap the harvest with enduring toil,

- Storing yearly little dues of wheat, and wine and oil;

- Till they perish and they suffer—some, ’tis whisper’d—down in hell

- Suffer endless anguish, others in Elysian valleys dwell,

- Resting weary limbs at last on beds of asphodel.

- Surely, surely, slumber is more sweet than toil, the shore

- Than labour in the deep mid-ocean, wind and wave and oar;

- O, rest ye, brother mariners, we will not wander more. (lines 154–173)

Themes

The form of the poem contains a dramatic monologue, which connects it to Ulysses, St. Simeon Stylites, and Rizpah. However, Tennyson changes the monologue format to allow for ironies to be revealed.[7] The story of The Lotos-Eaters comes from Homer's The Odyssey. However, the story of the mariners in Homer's work has a different effect from Tennyson's since the latter's mariners are able to recognize morality. Their arguments are also connected to the words spoken by Despair in Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, Book One. With the connection to Spenser, Tennyson's story depicts the mariners as going against Christianity. However, the reader is the one who is in the true dilemma, as literary critic James R. Kincaid argues, "The final irony is that both the courageous Ulysses and the mariners who eat the lotos have an easier time of it than the reader; they, at least, can make choices and dissolve the tension."[5]

Tennyson ironically invokes "The Lover's Tale" line 118, "A portion of the pleasant yesterday", in line 92 of The Lotos-Eaters: "Portions and parcels of the dreadful past". In the reversal, the idea of time as a protector of an individual is reversed to depict time as the destroyer of the individual. There is also a twist of the traditionally comic use of repetition within the refrain "Let us alone", which is instead used in a desperate and negative manner. The use of irony within The Lotos-Eaters is different from Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott" since "the Lady" lacks control over her life. The mariners within The Lotos-Eaters are able to make an argument, and they argue that death is a completion of life. With this argument, they push for a release of tension that serves only to create more tension. Thus, the mariners are appealing yet unappealing at the same time.[8]

In structure, The Lotos-Eaters is somewhere between the form of Oenone and The Hesperides. In terms of story, The Lotos-Eaters is not obscure like The Hesperides nor as all-encompassing as Oenone but it still relies on a frame like the other two. The frame is like The Hesperides as it connects two different types of reality, one of separation and one of being connected to the world. Like Oenone, the frame outlines the song within the poem, and it allows the existence of two different perspectives that can be mixed at various points within the poem. The perspective of the mariners is connected to the perspective of the reader in a similar way found in The Hesperides, and the reader is called to follow that point of view to enjoy the poem. As such, the reader is a participant within the work but they are not guided by Tennyson to a specific answer. As James Kincaid argues, "in this poem the reader takes over the role of voyager the mariners renounce, using sympathy for a sail and judgment for a rudder. And if, as many have argued, the poem is 'about' the conflict between isolation and communality, this meaning emerges in the process of reading."[9]

The poem discusses the tension between isolation and being a member of a community, which also involves the reader of the poem. In the song, there are many images that are supposed to appeal to the reader. This allows for a sympathy with the mariners. When the mariners ask why everything else besides them are allowed peace, it is uncertain as to whether they are asking about humanity in general or only about their own state of being. The reader is disconnected at that moment from the mariner, especially when the reader is not able to escape into the world of bliss that comes from eating lotos. As such, the questioning is transformed into an expression of self-pity. The reader is able to return to being sympathetic with the mariners when they seek to be united with the world. They describe a system of completion, life unto death, similar to Keats's "To Autumn", but then they reject the system altogether. Instead, they merely want death without having to experience growth and completion before death.[10]

Critical response

Tennyson's 1832 collection of poems was received negatively by the Quarterly Review. In particular, the April 1833 review by John Croker claimed that The Lotos-Eaters was "a kind of classical opium-eaters" and "Our readers will, we think, agree that this is admirable characteristic; and that the singers of this song must have made pretty free with the intoxicating fruit. How they got home you must read in Homer: — Mr Tennyson — himself, we presume, a dreamy lotos-eater, a delicious lotus-eater — leaves them in full song."[11]

In music

The British romantic composer Edward Elgar set to music the first stanza of the "Choric Song" portion of the poem for a cappella choir in 1907-8. The work, "There is Sweet Music" (op. 53, no. 1), is a quasi double choir work, in which the female choir responds the male choir in a different tonality. Another British romantic composer Hubert Parry wrote a half-hour-long choral setting of Tennyson's poem for soprano, choir, and orchestra.[12] In the song "Blown Away" by Youth Brigade, lines from the poem are used, such as "Death is the end of life; ah, why/Should life all labour be?/Let us alone. Time driveth onward fast" and "let us alone; what pleasure can we have to war with evil? is their any peace"

The poem inspired, in part, the R.E.M. song "Lotus". "There’s the great English poem about the lotus eaters, who sit by the river and — I guess it’s supposed to be about opium — never are involved in life. Maybe there’s a bit of that in there," said Peter Buck.[13]

See also

Notes

- Thorn 1992 p. 67

- Kincaid 1975 p. 17

- Hughes 1988 p. 91

- Kincaid 1975 p. 40

- Kincaid 1975 p. 39

- Kincaid 1975 pp. 40–41

- Hughes 1988 pp. 7, 12

- Kincaid 1975 pp. 3, 12, 31, 39

- Hughes 1988 pp. 87–89

- Hughes 1988 pp. 89–90

- Thorn 1992 qtd. pp. 106–107

- BBC Radio 3's The Choir program, broadcast 22 January 2012

- Q magazine, June 1999

References

- Hughes, Linda. The Manyfacèd Glass. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1988.

- Kincaid, James. Tennyson's Major Poems. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975.

- Thorn, Michael. Tennyson. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992.

The Lotos-Eaters public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Lotos-Eaters public domain audiobook at LibriVox