The Prowler (1981 film)

The Prowler (also known as Rosemary's Killer and The Pitchfork of Death internationally) is a 1981 American slasher film directed by Joseph Zito, written by Neal Barbera and Glenn Leopold, and starring Vicky Dawson, Farley Granger, Lawrence Tierney, and Christopher Goutman. The film follows a group of college students who are stalked and murdered during their graduation party by someone wearing a G.I. uniform.

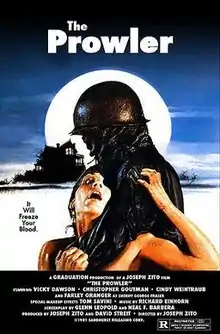

| The Prowler | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Joseph Zito |

| Produced by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Richard Einhorn |

| Cinematography | João Fernandes (as Raoul Lomas) |

| Edited by | Joel Goodman |

Production company | Graduation Films[1] |

| Distributed by | Sandhurst |

Release date |

|

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[2] |

| Box office | < $1 million[3] |

Filmed in late 1980 in Cape May, New Jersey, The Prowler premiered the following fall, and was independently distributed by Sandhurst Films. It was not a major commercial success, ranking 135th overall that year at the U.S. box office, and grossing less than $1 million.

Though it has received mixed reviews from critics, The Prowler developed a cult following in the years after its release, and has been noted for its hard-edged violence—showcasing special effects by Tom Savini—as well as its dreamlike atmosphere. It has been named one of the greatest slasher films of all time by several publications, including Complex[4] and Paste magazine.[5]

The Prowler is often compared to another slasher film of the same year with a similar plot, My Bloody Valentine.

Plot

On March 12, 1945 in Avalon, California, during World War II, a woman named Rosemary writes a letter to her boyfriend, breaking up with him. Three months later, Rosemary is attending a graduation dance with her new boyfriend Roy, who suggests they go out to lovers lane. While there, they are attacked by a mysterious prowler in an army combat uniform, who impales them both with a pitchfork and leaves behind a rose.

35 years later, college senior Pam MacDonald is making last-minute arrangements for that night's graduation ball, the first to be held since the 1945 murders. Helping Pam are her friends Lisa, Sherry and Sherry's love interest Carl. Later while visiting her boyfriend and the town's deputy, Mark London, Pam overhears a report of a prowler. She expresses her concern about Mark's safety because the sheriff is leaving town for a fishing trip. Mark reassures her and promises to meet her at the dance. Pam then heads back to the dorm to get ready and eventually leaves with her friends. Sherry stays behind to shower and receives a surprise visit from Carl. While undressing, he is attacked and killed with a bayonet. The killer then impales Sherry with a pitchfork in the shower.

At the dance, Pam spots Mark and motions him over. As he walks towards her, Lisa asks him to dance. Mark agrees, which upsets Pam. Mark then walks over to Pam and the two share a brief but tense exchange. A moment later, Lisa walks up and bumps Mark, which causes him to spill his drink on her dress. She returns to the dorm to change and is chased by the same prowler, but escapes. She runs outside into the wheelchair-bound Major Chatham who grabs her arm. Pam escapes his grasp and soon reunites with Mark. She tells him about the prowler so he investigates. After checking the dorm, Mark only finds bootprints and wheelchair tracks outside. The two then go investigate the Major's home. Pam realizes that his daughter was Rosemary and that her killer was never caught. Convinced the prowler from earlier is the same killer, Mark and Pam head back to the dance and warn the chaperone, Allison, about the possible danger.

Meanwhile, Lisa goes out to a nearby pool to cool off and encounters the killer, who slits her throat. Paul, Lisa's boyfriend, is arrested by Mark for public intoxication. Allison goes to find Lisa but is stabbed and killed also. Mark and Pam go to investigate the cemetery and discover an opened grave with Lisa's body in it. Mark tries to call the cabin that the sheriff went to, but is ignored by the site worker. Mark next calls the state police for help. He informs Pam that the state police told him that the reported prowler had been caught three hours earlier, and could not have killed Lisa.

Pam suspects that Lisa's killer is the same killer who murdered Rosemary and her boyfriend in 1945. They go to investigate Major Chatham's house again. Mark is attacked as the prowler chases Pam through the house. Otto appears and shoots the prowler, but he recovers and shoots Otto dead with a shotgun before again attacking Pam. While pinned to the ground, Pam manages to unmask the prowler, revealed to be Sheriff Fraser. Pam wrestles with the shotgun from his hands, then eventually puts it under his chin and pulls the trigger, killing Fraser.

The next day, Mark returns Pam to her dorm and she goes up alone. Discovering Sherry and Carl's bodies in the shower, she screams as Carl seems to come to life. She realizes Carl is dead and that him grabbing at her was a hallucination.

Cast

- Vicky Dawson as Pam MacDonald

- Christopher Goutman as Deputy Mark London

- Lawrence Tierney as Major Chatham

- Farley Granger as Sheriff George Fraser

- Cindy Weintraub as Lisa

- Lisa Dunsheath as Sherry

- David Sederholm as Carl

- Bill Nunnery as Hotel Clerk

- Thom Bray as Ben

- Diane Rode as Sally

- Bryan Englund as Paul

- Donna Davis as Miss Allison

- Carleton Carpenter as 1945 M.C

- Joy Glaccum as Francis Rosemary Chatham

- Timothy Wahrer as Roy

- John Seitz as Pat Kingsley

- Bill Hugh Collins as Otto

- Dan Lounsbery as Jimmy Turner

- Douglas Stevenson as Young Pat Kingsley

- Susan Monts as Young Pat Kingsley's Date

Themes

Critic Stephen Deusner of The Washington Post has interpreted The Prowler as a "a sly, strange statement about the stakes of war."[6] Deusner cites the film as transgressive in the genre due to its portrayal of a war veteran as its villain: "Not every movie could get away with casting a spurned veteran as its villain, especially not a WWII vet. Even in 1981, that generation was lionized for the austere morality of that conflict, set in sharp relief by the more controversial Vietnam War."[6] Scholar James Kendrick notes The Prowler as thematically linked to such slasher films as The Burning (1981), in which psychological trauma plays an integral role in the acts of murder committed, and where a present event provides the traumatized, maddened villain an "opportunity to take revenge on the guilty parties or their symbolic substitutes."[7]

Production

The Prowler was co-written by Glenn Leopold and Neal Barbera, son of Joseph Barbera.[2] Director Joseph Zito read the screenplay and was drawn to its "misty quality": "It had this strange, dreamlike mood in it. It wasn't trying to be real, it was trying to be surreal in a way."[2]

Initially, Zito had wanted to shoot The Prowler in Avalon, California, where it is set.[2] However, it was decided by Zito to shoot the film in Cape May, New Jersey instead, which he felt had a "ghost town quality."[2] The film was shot over a period of six weeks, which each consisted of six days' work,[8] beginning in October 1980.[9] Contemporaneous newspaper reports cite a budget of between $400,000 and $500,000,[9] though Zito has stated that the film ultimately cost $1 million to produce.[8] During production, the film had the working title Graduation.[10]

Because the film's death sequences were so special effects-intensive, the shooting schedule was crafted to prioritize the filming of them specifically, with whole days dedicated to one death scene.[11] The Inn at Cape May served as the building that appears in the dance sequences.[12] The Emlen Physick Estate served as the Chatham house, where the film's last act takes place.[13]

Release

Box office

Initially, Avco Embassy Pictures, who had previously released the slasher Prom Night (1980), expressed interest in distributing The Prowler.[14] The film was ultimately distributed independently in the United States by Sandhurst Films,[14] opening in the fall of 1981.[1] Overall, it ranked 135th at the U.S. box office for the year of 1981, earning less than $1 million during its theatrical run.[3]

Censorship

The Prowler was released under the alternate title Rosemary's Killer[15] in Australia and Europe in a cut that is missing almost a minute of Tom Savini's gore effects.[16] The German version omits all of the gore scenes (including the revelation of the killer's identity) and replaced the soundtrack with bird sounds for daytime scenes, cricket sounds for the night scenes, and Richard Enhorn's score with synthesizer music by an uncredited musician. This version goes by the title Die Forke des Todes (The Pitchfork of Death).[17]

The Encyclopedia of Horror reports that "Savini's particularly graphic special effects resulted in most of the murders being trimmed in the British release print."[18]

Critical response

Linda Gross of the Los Angeles Times panned the film for its violent content, adding that "Director Joseph Zito prowls around aimlessly without creating an authentic sense of locale. Instead, he delivers a spaced-out nightmare in which the characters act like zombies."[19] Stephen Deusner of The Washington Post described the film as "bloody, terrifying, [and] often sadistic... The Prowler is a war movie re-imagined as a slasher flick. And its message is clear: Take your military heroes for granted and they will come back and kill you."[6] Deusner also noted that the film is "gorgeously shot," but conceded that it "is never entirely satisfying. There are too many missed opportunities to transcend the genre’s schlock, too many passages where nothing happens, too many scares that fall flat."[6]

In a review for Slant Magazine, Chris Cabin compared the film to both John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) and William Lustig's Maniac (1980), writing: "These films remain popular due mostly to the films that are made proficiently as far as gore theatrics, tone, and mood are concerned, and in these terms The Prowler is certainly deserving of its modest fan base. What the film lacks in narrative drive, coherence, and performance, it makes up with thoughtful lighting, strong cinematography from Raoul Lomas and an uncredited João Fernandes, and, of course, Savini’s lovingly overblown and impossible splatter effects."[20] Film scholar John Kenneth Muir similarly praised the film, writing that it transcends many of its peers because of its "blunt-faced approach to violence" and Zito's "directorial virtuosity."[21]

The Encyclopedia of Horror notes that like My Bloody Valentine the film moves away from the genre's usual Midwestern setting, but that it does little with the new location, nor with its potentially interesting returning G.I. motif. Like Valentine, the film is judged as being certainly polished, atmospheric, and suspenseful, though hardly original."[18] Leonard Maltin gave the film a negative 1 1/2 out of a possible 4 stars, criticizing the film's plot calling it "illogical."[22] The Time Out film guide noted the film as "cravenly conformist in every department."[23]

AllMovie called it a "run-of-the-mill entry in the early '80s slasher film cycle" that "benefits from an unexpected amount of technical gloss, but has little else to offer."[24] In a retrospective, Dave Wilson of Dread Central noted the film's violent special effects and "sombre atmosphere" as strengths, though conceded that the film's characterization was bland.[25]

As of 2019, on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 67% approval rating with an average of 5.1/10 based on 6 reviews.[26] In the years since its release, the film has developed a cult following.[27] In 2017, Complex magazine named The Prowler the 24th-best slasher film of all time.[4] The following year, Paste included it in their list of "The 50 Best Slasher Movies of All Time,"[5] while the film's killer was ranked the 11th-greatest slasher villain of all time by LA Weekly.[28]

Home media

Blue Underground released the fully uncut version of The Prowler on DVD in 2002[29] and on Blu-ray in 2010. The extras include a trailer, a still and poster gallery, behind the scenes gore footage with Tom Savini, and an audio commentary with Joseph Zito and Tom Savini.[20]

In January 2019, Waxwork Records released the film's original score on vinyl as a double LP.[30]

References

- "The Prowler". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Los Angeles, California: American Film Institute. Archived from the original on January 18, 2018.

- Rockoff 2011, p. 131.

- Nowell 2010, p. 234.

- Barone, Matt (October 23, 2017). "The Best Slasher Films of All Time". Complex. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Vorel, Jim (August 8, 2018). "The Best Slasher Movies of All Time". Paste. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019.

- Deusner, Stephen M. (July 26, 2010). "The Goriest Generation: 'The Prowler,' on DVD". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016.

- Kendrick 2017, p. 319.

- Rockoff 2011, p. 132.

- Curran, Karen (November 4, 1980). "Cameras focus in Cape May". Courier-Post. Cape May, New Jersey. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Cape Eyed By Movie Makers". Cape May County Herald. Cape May, New Jersey. March 17, 1982. p. 17.

- Navarro, Meagan (October 10, 2018). "Brutal Slasher 'The Prowler' is a Showcase of Tom Savini's Best Work". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019.

- Reil, Maxwell. "These horror films have ties to South Jersey". Press of Atlantic City. Atlantic City, New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 9, 2018.

- "A South Jersey History Tour". Icona Resorts. January 7, 2019. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019.

- Rockoff 2011, p. 133.

- Rockoff 2011, p. 4.

- "Prowler, The (aka Rosemary's Killer)". Movie-Censorship.com. Retrieved December 23, 2017.

- "The Prowler". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016.

- Milne, Willemin & Hardy 1986, p. 370.

- Gross, Linda (October 14, 1981). "'The Prowler': Murder Once Again". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 95 – via Newspapers.com.

- Cabin, Chris (July 30, 2010). "Blu-ray Review: The Prowler". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019.

- Muir 2011, pp. 201–202.

- Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. New York, New York: Penguin Group. p. 1129. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- "The Prowler (1981)". Time Out. London. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019.

- Guarisco, Donald. "The Prowler (1981)". AllMovie. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014.

- Wilson, Dave J. (December 8, 2016). "Retrospective: The Prowler (1981) – 35 Years Later". Dread Central. Archived from the original on December 9, 2016.

- "The Prowler (1981)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Harper 2004, p. 143.

- Byrnes, Chad (October 22, 2018). "A Killer List: The Greatest Movie Slashers of All Time". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019.

- Long, Mike (August 13, 2002). "The Prowler". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017.

- Roffman, Michael (January 9, 2019). "Original score to cult slasher The Prowler has a date with vinyl". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019.

Sources

- Harper, Jim (2004). Legacy of Blood: A Comprehensive Guide to Slasher Movies. Manchester, United Kingdom: Critical Vision. ISBN 978-1-900-48639-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kendrick, James (2017). "Slasher Films and Gore in the 1980s". In Benshoff, Harry M. (ed.). A Companion to the Horror Film. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-33501-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milne, Tom; Willemin, Paul; Hardy, Phil (1986). Encyclopedia of Horror. London, England: Octopus Books. ISBN 0-7064-2771-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muir, John Kenneth (2011). Horror Films of the 1980s. 1. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-45501-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nowell, Richard (2010). Blood Money: A History of the First Teen Slasher Film Cycle. London, England: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-441-12496-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rockoff, Adam (2011). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film, 1978–1986. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-786-46932-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)