The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea

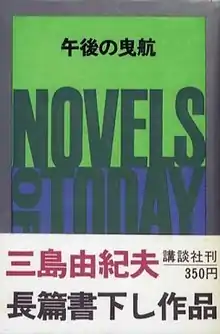

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (Japanese: 午後の曳航, meaning The Afternoon Towing) is a novel written by Yukio Mishima, published in Japanese in 1963 and translated into English by John Nathan in 1965.

First edition | |

| Author | Yukio Mishima |

|---|---|

| Original title | 午後の曳航 (Gogo no Eiko — Eng trans. Afternoon Shiptowing) |

| Translator | John Nathan |

| Cover artist | Susan Mitchell |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Philosophical fiction |

| Publisher | Kodansha Alfred A. Knopf (U.S.) |

Publication date | 1963 |

Published in English | 1965 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 181 pp |

| OCLC | 29389499 |

| 895.6/35 20 | |

| LC Class | PL833.I7 G613 1994 |

Plot

Much of the story is told following the actions of Noboru Kuroda, an adolescent boy living in Yokohama, Japan. He and his group of friends are good students but they are secretly a gang. They believe in conventional morality and are led by their schoolmate, the "chief". Noboru discovers in his chest of drawers a secret peephole into his widowed mother's bedroom and uses it to spy on her. Since Noboru has a keen interest in ships, his upper-class mother Fusako, who owns Rex, a European-style haute fashion clothing store, takes him to visit one near the end of the summer. There they meet Ryuji Tsukazaki, a sailor and second mate aboard the commercial steamer Rakuyo who has vague notions of a special honor awaiting him at sea. Ryuji has always remained distant from the land, but he has no real ties with the sea or other sailors. Ryuji and Fusako develop a romantic relationship, and their first night of sex is spied upon by Noboru, who watches through the peephole. As Noboru is watching his mother and the sailor, a ships horn sounds, which Ryuji turns towards. Noboru is elated, and believes he has witnessed the true order of the universe because Ryuji turns away from feeling and is drawn to the sea. He describes this as an “ineluctable circle of life”, (p. 13) in which Noboru sees himself unified with Fusako and Ryuji. However, the couple's second night together takes place at a hotel to Noboru's disappointment. The relationship continues even when Ryuji returns to sea.

At first Noboru reveres Ryuji, and sees him as a connection to one of the only meaningful things in the world- the sea. Noboru even tells the gang about his hero, insisting that “He’s different. He’s really going to do something.” (p. 50) Noboru is overjoyed when Ryuji returns to the Rayuko, leaving Fusako behind, because he sees this as “the perfection of the adults.” (p. 87) However, Ryuji eventually begins losing Noboru's respect, beginning when Ryuji meets Noboru and his gang at the park one day. Ryuji had just drenched himself in the water fountain, which Noboru is extremely embarrassed by, because he feels this is a childish action. Noboru takes issue with what he perceives as an undignified appearance and greeting by Ryuji. Noboru's frustration with Ryuji culminates when Fusako reveals that she and Ryuji are engaged.

While Ryuji is sailing, he and Fusako exchange letters, and they fall deeply in love. Returning to Yokohama days before the New Year, he moves into their house and gets engaged to Fusako. Ryuji then lets the Rakuyo sail without him as the New Year begins. This distances him from Noboru, whose group resents fathers as a terrible manifestation of a dreadful position. Fusako has lunch with one of her clients, Yoriko, a famous actress who is described as stolid and only trusts her fans. After Fusako breaks the news of her engagement to Ryuji, the lonely actress advises Fusako to have a private investigation done on Ryuji, sharing her disappointing experience with her ex-fiancé. Fusako ultimately decides to go forth with this idea in order to prove to Yoriko that Ryuji is the man he says he is. After they depart, the investigation is done and Ryuji passes the test. Fusako then plans to put him in a managing position at Rex. Noboru's secret of the peephole is discovered, but Ryuji does not punish him severely in order to fulfill his role of a lovable father, despite being asked to by Fusako.

As Ryuji and Fusako's wedding draws near, Noboru begins to grow more angry and calls an “emergency meeting” of the gang. Due to the philosophy of the gang they decide that the only way to make Ryuji a “hero” again is to kill and dissect him, yielding a preferably honorable death. The chief reassures the gang by quoting a Japanese law, which says, “Acts of juveniles under the age of 14 are not punishable by law.” He sees this as their last chance to fill the emptiness of the world and have witness over the life of men. Their plan is that Noboru (number 3 in the gang) will lure Ryuji to the dry dock in Sugita. The members of the gang each bring an item to assist in drugging of Ryuji and his dissection. The items include a strong hemp rope, a thermos for the teaspoons, cups, sugar, a blindfold, pills to drug the tea, and a scalpel. Their plan works perfectly; as he drinks the tea, Ryuji muses on the life he has given up at sea, and the no-longer-possible heroic life of love and death he has abandoned. The novel ends when Ryuji sees the chief putting on his gloves and, giving no attention to it, drinks his tea while lost in his thoughts.

Title

Translator John Nathan, in his memoir Living Carelessly in Tokyo and Elsewhere writes:

My completed translation was due on January 1, 1965, and I was still struggling to contrive an English title for the book. Mishima’s title was an untranslatable pivot on the word “tugging,” as in tugboat. Literally it meant “tugging in the afternoon,” Gogo no Eiko. The Japanese word for “glory,” written with different Chinese characters, is a homonym for “tugging” that every Japanese could be counted on to register upon reading the title. In the closing line, as the sailor drinks the drugged tea that will deliver him into the murderous hands of the children who plan to “tug” him back to the glory he has renounced, the narrator sardonically evokes the double entendre: “Glory, as anyone knows, is bitter stuff.”

All I had to show for months of worrying this was “Drag-out” or, more cleverly, as I thought, “Glory Is a Drag.” I sent my solutions off to Strauss, who responded in a comic note dated December 2, 1964:

I think you are on the right track with your proposed title, DRAG OUT, but not quite in that form. It lends itself to cheap jokes. Why does Mishima drag out the story? I wouldn’t be surprised if the key word were “drag” and something could be worked out with it. Using one word from the original title, what would you think of AFTERNOON DRAG? Come to think of it, a lot of homosexuals might be misled into buying the book.

There isn’t any reason we have to stick to the original, which is untranslatable. The word “Peep-hole” comes to mind, if the implications are not too sensational. I think in any case whatever we decide on ought to be discussed with Mishima.

I went to see Mishima, who seemed to relish the challenge. “Let’s come up with a long title, like Proust,” he said. Then he astonished me by rattling off half a dozen such titles in Japanese. I wrote them down as he spoke them. One seemed to translate itself: Umi no megumi wo ushinawarete shimatta madorosu—The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea. I conveyed this “authorized” title to Strauss and he was delighted.[1]

Themes

- Glory and honour

The themes of glory and honour are central to the story, and Mishima explores these ideas mainly through the character Ryuji Tsukazaki.

When Ryuji is first introduced, he is strongly associated with gold, a colour which often has positive connotations of triumph, achievement, and royalty. Gold is often highly regarded and respected, and can symbolise higher ideals. This therefore casts Ryuji as a representation of ultimate glory and honour. Furthermore, it is emphasised that this is "authentic gold", hence removing negative connotations of artificiality and pretentiousness, as well as establishing that Ryuji exists in the real world, and is not simply an illusory dream. Gold could also be a symbol of masculine energy and power, which highlights Ryuji's manliness. This masculinity is a point of pride and honour – Ryuji reflected later in the novel on how the sailor's life "impelled (him) toward the pinnacle of manliness", and agonised over whether he could "give it up". This aligns with the author's ideals as well – Mishima had been obsessed with hyper-masculinity and had strived to attain it himself, as exemplified by his endeavours in bodybuilding.

Ryuji's pursuit of glory deeply affects Noboru. For the thirteen-year-old Noboru, Ryuji is a hero, a "luminous evidence of the internal order of life". Noboru is therefore determined to protect the glorious image of Ryuji after he witnesses Ryuji making love with his mother ""If this is ever destroyed, it'll mean the end of the world." Noboru murmured, barely conscious. I guess I'd do anything to stop that, no matter how awful!" Noboru's obsession with Ryuji and the idea of glory he represents ultimately lead to Ryuji's murder.

Death is strongly associated with glory in Mishima's text. Mishima had said in one of his interviews: “It is natural for me to find it obscene that human beings live only for themselves. You might call this the boredom of living ... they get bored living just for themselves ... always think of living for some kind of ideal. Because of this, the need to die for something arises. That need is the “great cause” people talked about in the past. Dying for a great cause was considered the most glorious heroic or brilliant way of dying”[2] Thus in a certain way Mishima hereby personifies his ideology in Ryuji's character. When Ryuji was first introduced as an almost god-like figure, attention was drawn to his "dangerous, glittering gaze", hence firmly linking glory with danger, and by extension, death. Glory in the text is also found in the turbulence and uncertainty of the sea and in the danger of death that the sea may bring about: "They were consubstantial: glory and the capsized world. He longed for a storm".

Glory is presented as inherently dangerous in the novel, as evident in how Ryuji felt "glory knifing toward him like a shark from some great distance". The sharp violence and peril associated with knives, as well as the predatory nature of sharks, illustrates the great risks that came with the pursuit of glory.

When Ryuji gives up his Grand Cause and settles onto the land, he loses his life. Before his death, his thoughts drift back to the glory that he has longed to pursue: " Emperor palms. Wine palms. Surging out of the splendor of the sea, death had swept down on him like a stormy bank of clouds. A vision of death now eternally beyond his reach, majestic, acclaimed, heroic death unfurled its rapture across his brain. And if the world had been provided for just this radiant death, then why shouldn't the world also perish for it!"

- Alienation

The theme of alienation is shown through the isolation of the characters Noboru and Ryuji Tsukazaki. The character Noboru is portrayed as isolated in the book as he seems to not understand all that going around him. The idea of westernisation is also brought into play as Noboru is seen as very traditional yet his mother is westernised, which is seen through a physical description of her room. In the physical description of Fusako's (Noboru's Mother) room, Mishima constantly refers back to where a certain element is imported from. Written through Noboru's perspective we can see that because he is not westernised and is still very much traditional to his culture he notices these elements- where the item is from. Through this separation due to westernisation the idea of Noboru being alienated is brought up as he is detached from even the closest person to him- his mother. In the book Mishima describes "Noboru couldn’t believe he was looking at his mother’s bedroom; it might have belonged to a stranger." Through this quote we can see that not only is he not close to his mother but that he feels as though his mother is a stranger which reinforces the idea of alienation.

The theme of alienation is highlighted also by the character Ryuji Tuskazaki due to his detachment to society. Mishima describes ‘’He grew indifferent to the lure of exotic lands. He found himself in the strange predicament all sailors share: essentially he belonged neither to the land nor to the sea. Possible a man who hates the land should dwell on shore forever." The phrase "belonged neither to the land nor to the sea" implicates the idea of alienation as there is only land and sea, but Tsukazaki belongs to neither which questions the reader where does he belong?

In conclusion, both Ryuji and Noboru feel detached from society, and in various degrees and for different reasons, they both try to relieve their isolation. In Fusako, Ryuji finds the anchor for which he has been searching, and moves quickly into the comfortable life of lover and father. Noboru has chosen to turn his loneliness to hatred and seek for strength using murder. The prevalence of alienation and loneliness as a theme can be linked back to Mishima's own background. Not unlike Noboru and The chief, Mishima dreamt that Japan was restored to its original power and glory. Mishima's dislike towards Japan's westernization is reflected through “Chief’s contempt of adult nature.

- Gender roles

The role of females in the novel seems sparse – the main female character is Fusako, who is the love interest of Ryuji and the mother of Noboru. In some ways, she is one of the most important characters in the novel as her relationship with Ryuji is the unbecoming of him in some ways. The balance of their relationship seems quite equal and Fusako is portrayed to be the perfect partner and housewife. She is also portrayed to be an independent woman who is doing better in her business than Ryuji is with his work. She is also seen to be diplomatic with her clients in her business. Male characters dominate the book, but most seem dependent or obsessed with some sort of notion – Ryuji with his quest for glory, Noboru and his need to conform to his ‘gang’s’ ideology, and the chief and his obsession with his ideas surrounding life. Males in the book also seem to be the characters who are pursuing a specific goal, unlike Fusako, who seems to be a static character throughout the novel.

- Dehumanization

Within the novel, Mishima uses the gang to portray his belief in the futility of human life and society.[1] He uses the gang to show how the process of dehumanization works and affects society. All six members of the gang are alienated from the society in which they live. The gang believes emotions impede them from living authentically in a corrupt and controlling society, so the chief conditions them to feel numb through overstimulation, such as by viewing pornography and—most graphically—killing and dissecting a cat. The chief believes that suppression of one's excitement or disgust in such situations will erode emotions and allow the gang to live “real” are authentic lives outside of the confines and control of adults and conventional society. Another way that Mishima shows the alienation of the gang is by having the chief assign them numbers in place of their given names, thereby erasing identity given to them by their parents. Even the main character, Noboru, is known in the gang as number three. Despite Noboru's efforts to achieve an emotionless state, however, he maintains a belief that meaning might be found in the sea. His attempt to find meaning is evident in his love for ships and his initial reverence and respect for Ryuji Tsukazaki, a merchant sailor whose commitment to sea is illustrated when Tsukazaki turns toward the sound of a ship's horn in the bedroom scene early in the novel (12). Eventually, however, even Tsukazaki fails to live up to Noboru's expectations, and Noboru begins keeping a tally of the sail crimes Tsukazaki commits as the sailor falls in love with Noboru's mother, moves in, and gets engaged to be married. Noboru's alienation and disappointment in Tsukazaki and his mother's appropriation of western fashion aligns with Mishima's own feelings of dehumanization and marginalization due to his assumed homosexuality and conflicting feelings about Japanese society in a post-war world.

- Post-WWII Japan

The entire novel is an allegory for the situation following Japan's defeat after World War II.[2] This can be seen by the characters and their representation of the different components of Japan that surfaced following the war. Noboru and his ‘gang’ represent Mishima's values and ideals. Noboru's mother, Fusako, represents post-war westernization of Japanese culture. Ryuji represents old Japan, and he is attracted to the sea, something that represents glory and a special destiny for him. Mishima himself was a Japanese nationalist who hated seeing Japan influenced by the Western world after World War II. This is comparable to Ryuji's eventual “fall from grace with the sea” by marrying Fusako. In effect, their marriage represents Ryuji capitulating to post-war westernization. Noboru's killing of Ryuji for marrying Fusako can be seen as a foreshadowing for Mishima's own attempted coup d'état of the Japanese government, an attempt to regain some of Japan's heritage and tradition lost because of post-war westernization. At the end of the novel, Mishima explores the choices that Ryuji has made. Ryuji seems to regret his decision to give up the sea and ‘majestic, acclaimed, heroic death,’ which is likened to glory. Instead, he has been ‘abandoned,’ condemned to ‘a life bereft of motion.’ The ‘life bereft of motion’ refers to the surrender of Japan to western values, and the ‘majestic, acclaimed, heroic death’ refers to sticking by Japanese traditions and values.

Characters

- Ryuji Tsukazaki

Ryuji Tsukazaki is a sailor and Fusako Kuroda's lover. Throughout the book it is shown that Ryuji (also known as the sailor) sees himself destined for glory though at that point he is not sure as to what kind of glory he will receive. Ryuji falls in love with Fusako and later he marries her, becoming a father-figure to her son Noboru. This new love and the failure to achieve glory in the presence of the sea lead him to determine to retire from the sea, thus outraging Noboru and causing him to take action.

- Noboru Kuroda

Noboru is a thirteen-year boy and the son of Fusako. He is the protagonist of this novel. He is influenced by his friends, especially the chief who thinks “..society is basically meaningless, a Roman mixed bath.” They have nihilistic view of the world and Noboru, after killing the innocent cat thinks murder would “fill those gaping caves” and he and his gang can achieve “real power over existence.”

Although he thinks there is little meaning in life, he is fascinated with the strength and vastness of the sea as he thinks it has “internal order of life.” Chief also explains him that the sea is “more permissible than any of the few other permissible things.” Therefore, he idealises Ryuji who lives and works in the ship. He is delighted when he sees his mother and the sailor are in love, saying “...Ryuji was perfect. So was his mother.”

However, he becomes extremely disappointed when he found out that the sailor was different from what he thought, “...But he hadn’t said anything of the kind. Instead he had offered his ridiculous explanation.” Eventually when Ryuji gives up his life as a sailor for Fusako and Noboru and destroyed the heroic image that Noboru had, Noboru and his gang punish him for giving up his glory.

- Fusako Kuroda

Noboru's mother. Fusako is a widowed woman who runs a luxury goods import store called Rex within the town of Yokohama, Japan. After meeting Ryuji Tsukazaki during a ship tour, Fusako falls in love. Eventually Ryuji leaves once again for sea, and Fusako vows that she will not be a “harbor whore” and does her best to not let Ryuji's departure affect her. In December of the same year, Ryuji returns from sea and proposes to Fusako. Fusako accepts and fully invites Ryuji into her and Noboru's life. Fusako strives towards elegance, as is demonstrated by her stocking of luxury goods. Her stocking of luxury goods is also representative of her western leanings, because all of the goods she stocks are of western origin. In addition to only stocking western goods, Fusako partakes in very few Japanese traditions. She offers coffee instead of tea, goes to restaurants that serve non traditional food, and only celebrates old traditions on special occasions such as New Years.

- Mr. Shibuya

The manager of Rex. He is an older man who is described as having “devoted his life to elegance in dress,” (p. 25). Mr. Shibuya is shown as having more concern over the needs of others than his own. He especially feels a sense of responsibility for Fusako, because he has been helping her since her husband died five years previous to the opening of the novel. Mr. Shibuya echoes the traits of the goods he sells. He is elegant, refined, and exists for the sole purpose of bettering someone else's life.

While he is only present for a small portion of the novel, his role is rather substantial. Mr. Shibuya, by aiding Fusako with the store, is a catalyst for Fusako's turn away from traditions, which then helps Noboru cement himself in the chief's ideology.

- Yoriko Kasuga

A famous movie actress who is obsessed with public acclaim and her image. However, Yoriko has a dark side. She's a woman who has experienced much struggle in her life. She only finds happiness and satisfaction within the praise of others. This happiness is difficult for Yoriko to achieve, because she feels she only has two friends; her fans and Fusako. The one time she finds the praise and satisfaction she desires, it is in the arms of a man. Naturally, Yoriko becomes engaged to this “savior” and she thrives. Later it is revealed that he has been cheating on her and is the father of several children, all of whom were born out of wedlock. The breaking of her engagement drives Yoriko to attempt suicide. However, none of the public ever know anything about it because her public image is still the most important part of her.

- Numbers 1, 2, 4, and 5

These numbers are the only identifiers given to the other boys in the chief's gang. All of these boys come from wealthy families and are top students in their class. The amount of “perfection” in their lives is what drives the boys into the open arms of the chief's teachings. As is typical of wealthy families, the boys’ parents are rarely home and the large houses in which they live are cold and empty. The only attention they get from adults is from teachers praising their work and adults who love kids. Neither of these interactions come off as genuine, leading the boys to believe that there is no meaning in the world. Believing there is no meaning causes the boys to become cold and harsh. This then allows them to find atrocities, such as the murder of the kitten and Ryuji, beautiful. In addition to not believing there is meaning in the world, the chief is the first person in a position of authority that actually pays attention to the boys, which then makes it easier for them to accept his teachings.

- The Chief

A thirteen-year-old boy, known only as “The Chief” to his gang, which Noboru is part of, leads an investigation to understand existence through analysis and criticism of human nature, social structure and life. “The Chief” is arrogant and dispassionate, but is also precocious. His hatred towards the normality of life has led him to committing extreme acts, namely his butchering and subsequent dissection of a kitten.

Context

The entire novel is an allegory for the situation following Japan's defeat after World War II. This can be seen by the characters and their representation of the different components of Japan that had surfaced following the war. Noboru and his ‘gang’ represent old Japanese traditions and values. Noboru's mother, Fusako, represents westernisation of the Japanese culture. The sea represented glory, and Ryuji's attraction towards this notion was in itself a metaphor for Japan's quest in the war. Some of the gang's inhumane actions symbolise how some of the decisions made by the Japanese in the war were also inhumane. Thirteen year old boys killing a baby cat goes against usual human nature, and in the war there were kamikaze bombings, where a person would kill themselves for a desperate offensive attack and a glorious death. At the end of the novel, Mishima explores the choices that Ryuji has made. Ryuji seems to regret his decision to give up the sea and ‘majestic, acclaimed, heroic death’, which is likened to glory. Instead, he has been ‘abandoned’, condemned to ‘a life bereft of motion’. The ‘life bereft of motion’ refers to the surrender of Japan to western values, and the ‘majestic, acclaimed, heroic death’ refers to sticking by Japanese traditions and values. Through these melancholy destinies that Ryuji has chosen from, Mishima expresses his thoughts on how the Japanese seem to be condemned to a glorified death or bottomless limbo.

Adaptations

The novel was adapted into the film The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea starring Kris Kristofferson and Sarah Miles in 1976 by Lewis John Carlino. The setting was changed from Japan to England.

An opera by Hans Werner Henze, Das verratene Meer, is based on the novel; it was premiered in Berlin in 1990. The reception was not good. A revised version, entitled Goko no Eiko written by Henze under the initiative of the maestro conductor Gerd Albrecht, was adapted to a Japanese libretto close to Mishima's original. The world premiere of this Japanese version was given at the Salzburger Festspiele in 2005 and released on the label Orfeo, without any libretto included.

References

- 1940-, Nathan, John (2016-08-06). Living carelessly in Tokyo and elsewhere : a memoir. New York. ISBN 978-1416553465. OCLC 951936590.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Interview with Mishima with English Subtitles".

Mishima, Y., & Nathan, J. (1972). The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea: Yukio Mishima.

Aydoğdu, M. (May 2012). Is There a Way Out?: The Inhuman Politics of Noboru and His Gang in Yukio Mishima's The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea. Çankaya University Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Volume 9: Issue 1, pp. 157–164. http://cujhss.cankaya.edu.tr/tr/9-1/14%20Aydogdu.pdf

JoV (September 7, 2010). Yukio Mishima: The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea. Retrieved from https://bibliojunkie.wordpress.com/2010/09/07/yukio-mishima-the-sailor-who-fell-from-grace-with-the-sea/