The Shepherd King

The Shepherd King is a 1923 American silent biblical epic film directed by J. Gordon Edwards and starring Violet Mersereau, Nerio Bernardi, and Guido Trento. It is a film adaptation of a 1904 Broadway play by Wright Lorimer and Arnold Reeves. The film depicts the biblical story of David (Bernardi), a shepherd prophesied to replace Saul (Trento) as king. David is invited into Saul's court, but eventually betrayed. He assembles an army that defeats the Philistines, becomes king after Saul's death in battle, and marries Saul's daughter Michal (Mersereau).

| The Shepherd King | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | J. Gordon Edwards |

| Produced by | William Fox |

| Screenplay by | Virginia Tracy |

| Based on | The Shepherd King ... a Romantic Drama in Four Acts and Five Scenes by Wright Lorimer and Arnold Reeves |

| Starring | Violet Mersereau |

| Cinematography | Benny Miggins |

| Distributed by | Fox Film Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 9 reels |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent (English intertitles) |

Advertising for the film tried to take advantage of the popular interest in Egypt following the discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb, despite only an introductory scene in the film taking place in Egypt. The film opened to mixed reviews from contemporary critics. In part due to direct competition from another biblical epic, Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments, The Shepherd King was not considered successful. Like many of Fox Film's early works, it was likely lost in the 1937 Fox vault fire.

Plot

Moses leads the Israelites past the Giza pyramids and the Great Sphinx on their way out of Egypt toward the Promised Land.[1] Generations later, King Saul of Judea defies prophecy by making a burnt offering to prepare for an attack against the Philistines without waiting for the arrival of the prophet Samuel. In response, Samuel tells Saul that he will lose the throne. Samuel searches for someone worthy to be the next king, and selects the young shepherd David, secretly informing the boy that he will become king at some future time.

Saul is depressed and has his son Jonathan befriend David and bring him to the palace. David's music improves the king's mood. While at court, the shepherd meets Princess Michal, Saul's daughter, and they begin to fall in love with each other. After he uses a sling to kill a lion that was threatening Michal's life, he is permitted to face the Philistine champion, Goliath, in combat. David kills Goliath with the same sling used to kill the lion.

Saul offers David the opportunity to marry the princess if he can defeat the Philistine army and claim one hundred of the enemy banners as proof of their defeat. However, Saul has become convinced that the defeat of Goliath is evidence that David is the man Samuel prophesied would replace him as king. David prepares to face the Philistines with only a small military force, while Doeg, a member of Saul's court, warns them of the impending attack. An escaped prisoner meets with David and informs him that the Philistines are preparing an ambush; David uses this knowledge to defeat the enemy forces. Returning victorious to the court, Saul attempts to kill David, then banishes him.

David begins to gather an army of his own. Doeg, assisting the Philistines, attacks Saul's palace. Both Saul and Jonathan die during the battle, but David's forces intercede and destroy the attacking army. David saves Michal from the invaders, is crowned king by popular acclamation, and marries the princess.[2][3][4][5]

Cast

- Violet Mersereau as Michal

- Edy Darclea as Herab

- Virginia Lucchetti as Adora

- Nerio Bernardi as David

- Guido Trento as Saul

- Ferruccio Biancini as Jonathan

- Sandro Salvini as Doeg (credited as Alessandro Salvini)

- Mariano Bottino as Adriel

- Samuel Balestra as Goliath

- Adriano Bocanera as Samuel

- Enzo Di Felice as Ozem

- Eduardo Balsamo as Abimelech

- Americo Di Giorgio as Omah

- Ernesto Tranquili as Jesse[2]

Edwards's son Jack McEdward, credited here as Gordon McEdward, appears as an Egyptian prisoner.[2][6]

Production

Wright Lorimer and Arnold Reeves wrote a play based on the biblical story of David, titled The Shepherd King ... a Romantic Drama in Four Acts and Five Scenes.[2] It debuted on Broadway on April 5, 1904 at the Knickerbocker Theatre, where it ran for 27 engagements.[7] The play was well-received by critics, especially the performance of Margaret Hayward as the Witch of Endor.[8][9] Following this initial success, it was revived twice: at the New York Theatre for 48 performances beginning February 20, 1905;[10] and for 32 performances at the Academy of Music beginning December 3, 1906.[11] From 1908 to 1910, Lorimer contracted with theater producer William A. Brady to have the play staged at other venues in the United States and Canada; this relationship broke down and Lorimer sued Brady over the handling of the production and its proceeds.[12] In December 1911, with the suit still pending, Lorimer committed suicide. Brady permitted all rights to The Shepherd King to pass to Lorimer's widow.[13]

The first film based on the Lorimer and Reeves play was directed by J. Stuart Blackton for Vitagraph Studios in 1909. This one-reel short film, titled Saul and David, was an unauthorized adaptation that did not credit its source.[14] Following the success of biblical epics Salomé (1918) and The Queen of Sheba (1921),[15] and a history of successful adaptations of theatrical works, Fox obtained the rights to The Shepherd King, in part to ensure that the well-regarded play could be mentioned freely in advertising.[16]

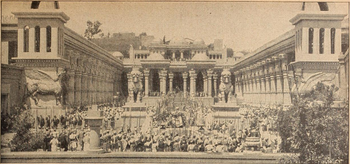

As with many historical films produced by Hollywood studios in the 1920s, including Edwards's earlier Nero (1922), an Italian crew was used;[17] actor Henry Armetta accompanied the production as an interpreter.[18] For The Shepherd King, most of the cast were also Italian.[19] Some scenes were filmed in Rome; Saul's palace was a constructed set, built with the assistance of the Capitoline and Vatican Museums.[4] This structure, measuring 540 by 180 by 60 feet (165 m × 55 m × 18 m), was among the largest built for a film's production at that time.[20] Most exterior scenes, however, were filmed on location in Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan,[4][19] including staging in both Jericho and Jerusalem.[20]

Howard Carter's discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 had sparked a wave of Egyptomania.[15] Seeking to capitalize on this trend, Fox had Edwards add an opening sequence to the film based on the Exodus.[21] This introduction was filmed in Egypt, with the Sphinx and pyramids in the background.[19] Because it was produced largely for promotional purposes, it is unrelated to the rest of the film, although Edwards did provide intertitles that attempted to frame it as a background for the story of David.[21]

Unlike either the stage production or Saul and David,[22] the battle between David and Goliath was featured on screen.[23] A chariot race was also included in an effort to capitalize on the success of a similar scene in The Queen of Sheba.[15] Some scenes required large numbers of extras. Photoplay reported that Edwards's crew avoided potential religious conflict while filming in Jerusalem by having British troops costumed as Arabs.[20] The largest battle scene used fifteen thousand horsemen, who were members of Transjordan's military provided by Emir Abdullah.[4][24]

Several scenes were hand-colored for release,[24] including images of a red lantern hung above Saul's throne.[4]

Release and reception

The Shepherd King was scheduled for a November 25, 1923 release;[1] modern sources, including the American Film Institute, report that the film was released on that date.[2][25] Its New York premiere, on December 10 at the Central Theatre, was met with initially positive reviews in the local newspapers; the New York Evening Journal labelled it the best of Edwards's films.[26] Moving Picture World's C. S. Sewell also reviewed the film favorably, praising the battle scenes and Bernardi's role as David.[3] Many reviewers held more mixed opinions. The New York Times found the film beautiful, but faulted its slow pacing and the number of close-up shots.[4] Laurence Reid, writing for Motion Picture News, also considered the film too slow and complained that too much of the plotline was conveyed in intertitles rather than action.[27] At the Los Angeles Times, Helen Klumph was scathing, declaring the film "simply incredibly bad".[28] Agnes Smith of Picture-Play Magazine compared The Shepherd King to a "third-rate" Italian opera and deemed it inferior to Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments (1923).[29]

The Shepherd King performed poorly at the box office, primarily due to competition with The Ten Commandments,[30] however other factors contributed to its commercial failure. Mersereau lacked the appeal of Theda Bara or Betty Blythe, who had starred in Edwards's earlier, more successful works.[31] The rest of the cast were primarily unknown to the American audience.[32] Additionally, Fox's advertising strategies for The Shepherd King were sometimes counterproductive. Promotional material for the film, including the film poster,[15] primarily focused on Egyptian imagery. However, the film itself had very little to do with Egypt or the Exodus story; 1,220 shots were registered for copyright in association with the film, but only eight of those were filmed in Egypt.[19] The Shepherd King was also marketed as "the World's greatest romance", a tagline recycled from The Queen of Sheba, but the biblical relationship between David and Michal is not overall a romantic one.[31] A 1924 advertising campaign encouraged Odd Fellows to see the film by focusing on the relationship between David and Jonathan, which is an important part of Odd Fellows ritual.[33][34]

The Shepherd King is believed to be lost. The 1937 Fox vault fire destroyed most of Fox's silent films,[35] and the Library of Congress is not aware of any extant copies.[36]

References

- "Fox releases for November 25 week". Moving Picture World. 65 (4): 418. November 24, 1923.

- "The Shepherd King". AFI Catalogue of Feature Films: The First 100 Years 1893–1993. American Film Institute. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- Sewell, C. S. (December 22, 1923). "The Shepherd King". Moving Picture World. 65 (8): 707.

- "The screen". The New York Times. 73 (24062): 26. December 11, 1923.

- Barrett, E.E. (March 1925). "The Shepherd King". Pictures and the Picturegoer. 9 (51): 12–13.

- "J. Gordon Edwards back from Europe". Motion Picture News. 28 (18): 2111. November 3, 1923.

- "The Shepherd King". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- Grant, Percy Stickney (May 7, 1904). "A Biblical story on the stage". Harper's Weekly. 48 (2472): 736.

- Lowrey, Carolyn (May 19, 1904). "Margaret Hayward, a young character actress". Broadway Weekly. 3 (66): 3.

- "The Shepherd King". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "The Shepherd King". Internet Broadway Database. The Broadway League. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- "Wright Lorimer sues Brady". The New York Times. 60 (19577): 7. August 31, 1911.

- "Despondent actor a suicide by gas". The New York Times. 61 (19691): 6. December 23, 1911.

- Shepherd 2013, pp. 66–68.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 148.

- Shepherd 2013, p. 205.

- Muscio 2013, p. 163.

- Mallory, Mary (December 16, 2013). "Henry Armetta, excitable support". L.A. Daily Mirror. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- Shepherd 2013, p. 208.

- Howe, Herbert (August 1922). "When in Rome do as the Caesars did". Photoplay. 22 (3): 75–76, 120.

- Shepherd 2013, pp. 208–209.

- Shepherd 2013, pp. 206–207.

- "'Shepherd King' an exceptional spectacle". Motion Picture News. 28 (20): 2381. November 17, 1923.

- Solomon 2001, p. 166.

- Solomon 2011, p. 285.

- "Fox's newest makes hit". Moving Picture World. 65 (9): 798. December 29, 1923.

- Reid, Laurence (December 22, 1923). "The Shepherd King". Motion Picture News. 28 (25): 2900.

- Klumph, Helen (December 16, 1923). "'Anna' rated great in East / New York sees some big hits". Los Angeles Times. 43: III.27, III.32.

- Smith, Agnes (March 1924). "The screen in review". Picture-Play Magazine. 20 (1): 56–60.

- Page 2016, p. 104.

- Shepherd 2013, p. 207.

- Shepherd 2013, pp. 207–208.

- "Odd Fellows as tieup for 'Shepherd King'". Motion Picture News. 29 (3): 252. January 19, 1924.

- Grosh 1860, pp. 126–128.

- Slide 2000, p. 13.

- "The Shepherd King / Violet Mersereau [motion picture]". American Silent Feature Film Database. Library of Congress. January 5, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

Sources

- Grosh, Aaron B. (1860). The Odd-Fellow's Manual. H. C. Peck & T. Bliss. OCLC 15802306.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muscio, Giuliana (2013). "In hoc signo vinces: historical films". In Bertellini, Giorgio (ed.). Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader. John Libbey Publishing. pp. 161–170. ISBN 978-0-86196-670-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Page, Matthew (2016). "There might be giants: King David on the big (and small) screens". In Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda (ed.). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 101–118. ISBN 978-1-61451-561-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shepherd, David J. (2013). The Bible on Silent Film: Spectacle, Story, and Scripture in the Early Cinema. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-04260-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shepherd, David J. (2016). "Scripture on silent film". In Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda (ed.). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 139–160. ISBN 978-1-61451-561-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Slide, Anthony (2000). Nitrate Won't Wait: A History of Film Preservation in the United States. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0836-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Solomon, Aubrey (2011). The Fox Film Corporation, 1915–1935: A History and Filmography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6286-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Solomon, Jon (2001). The Ancient World in the Cinema (revised ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08337-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Shepherd King. |