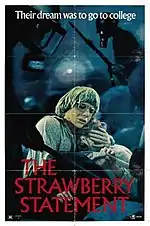

The Strawberry Statement (film)

The Strawberry Statement is a 1970 American drama film about the counterculture and student revolts of the 1960s, loosely based on the non-fiction book by James Simon Kunen (who has a cameo appearance in the film) about the Columbia University protests of 1968.

| The Strawberry Statement | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Stuart Hagmann |

| Produced by | Robert Chartoff Irwin Winkler |

| Written by | Israel Horovitz |

| Based on | the novel by James S. Kunen |

| Starring | Bruce Davison Kim Darby Bud Cort Andrew Parks Kristin Van Buren Kristina Holland Bob Balaban |

| Music by | Ian Freebairn-Smith |

| Cinematography | Ralph Woolsey |

| Edited by | Marje Fowler Roger J. Roth Fredric Steinkamp |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date | June 15, 1970 |

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million[1] |

Premise

The film details the life of one student. Its setting is not Columbia University in New York City but a fictional university in Stockton, California, which is based on San Francisco State College (later San Francisco State University). Thunderclap Newman's "Something in the Air" and numerous other rock songs are used on the soundtrack.

Plot

Simon, a student at a fictional university in San Francisco is indifferent to the student protests around him, until walking in on a naked woman in his dormitory roommate's bed. While she quickly runs over to the toilets to dress, Simon protests to his roommate that their time should only be devoted to studying, so they can get good jobs and much money.

Coming back clothed, the woman refuses setting another date with the roommate because she'll be busy protesting. She explains the university's plan to construct a gymnasium in an African-American neighborhood, thus causing conflict with the local African American population. She tells him that she and others plan to take over one of the university's buildings.

Simon later experiences love at first sight with a female student and uses his photographer position in the college's journal to photograph her. Following her into the university building the students are taking over, he joins the takeover just by being there. She approaches him while he boringly fools around in the toilets. She says her name is Linda and asks him to rob a food store with her so the striking students can eat.

In a later student protest, Simon is arrested. He then tells Linda he is not a radical like her. He does not want to "blow up the college building" after doing his best to be accepted into the school in the first place. Linda later claims she can't see someone who is not likewise dedicated to the movement. Nevertheless, she announces temporarily leaving college to decide for sure.

In the showers, right-wing jock George beats up Simon, who decides to take advantage of the situation and use his injuries from George to fake police brutality. Gaining fame, his friend tells him "a white version of page 43" of Simon's National Geographic looks like him.

Alone in a filing room, a large breasted redhead with a tight sweater smiles at Simon. Seeing his injured lip, she puts his hands on her right breast and asks if it feels better now. She then takes off her sweater telling Simon "did you know Lenin loved women with big breasts?" After quick flashes of her breasts, Simon confirms liking them, but asks her if she saw The Graduate. Replying no, she takes him between some filing cabinets and takes off his belt. To her surprise, Simon does not want people to see whatever it is she plans to do to with him. When asking her if she at least locked the door, she confirms unconvincingly and immediately opens up some filing cabinets to hide them. Simon is worried, but she promises him no one will know. She then says she will give him something a "hero" like him deserves, ducks down and gives him an off-screen blowjob, zooming up on Che Guevara's famous poster staring in the air in its implacable expression.

After Linda returns, she announces her decision to be with Simon. They spend the rest of that day together – and implicitly the night. The following day, they make out in a park when a group of African-Americans approaches them. The anti-racism Caucasian rebels fear for their lives. One African-American drops Simon's camera to the ground and stomps on it, but the group then simply leaves. A furious Simon meets the strikers, saying those they help are no different than the cops and the establishment and questioning why they should help those who disrespect and even threaten him.

Simon re-thinks his comparison, though, after visiting none other than George the – now leftist – jock in the hospital. George's leg is in a cast after right-wing jocks beat him up while cops watched. Simon goes to personally warn the dean's secretary to call off the construction of the gymnasium or risk a war. A group of African American students then show up, proving Simon's previous generalization wrong.

Eventually, a SWAT team crushes the university building takeover in seconds with tear gas. With the strikers all lying choking, the SWAT members pull out African Americans from the crowd and beat them up with police clubs. When the others protest, they get the same treatment.

With Linda being carried away kicking and screaming, Simon takes on a group of cops all by himself and segments of his happier times in college flash before the viewers' eyes.

Cast

- Bruce Davison: Simon

- Kim Darby: Linda

- Bud Cort: Elliott

- Murray MacLeod: George

- Tom Foral: The Coach

- Bob Balaban: Elliott

- Greta Pope: Song Leader

Production

Clay Felker, editor of New York magazine, showed producer Irwin Winkler a column James Kunen had written and told him it was going to be a book (it would be published in 1969). He read it and bought the film rights with partner Bob Chartoff. "We thought it could create understanding – the schism was so great between the generations then", said Winkler. "It was an important subject. These youths who are looked upon as anarchists are really just American kids reacting to problems in our society. Here was a story about an ordinary guy becoming an anarchist." [2]

Winkler had seen The Indian Wants the Bronx and It's the Called the Sugar Plum by Israel Horovitz and asked if he had an idea how to adapt the book. Horovitz pitched the movie to MGM saying it should be shot at Columbia. "At the time, there was a student group that had shot a lot of black and white documentary footage of the strikes at Columbia", he said. "I wanted to intercut this documentary footage with the fiction that I planned to write. "[3]

The pitch was successful as MGM announced they would make it in May 1969.[4] MGM's president at the time was "Bo" Polk and the head of production was Herb Solow.[5]

Israel Horovitz was signed to do the screenplay.[6] He said he wrote ten drafts over two years.[7]

François Truffaut was offered the film to direct but turned it down. The job eventually went to Stuart Hagmann who had worked in television and advertising.[8][9]

Horovitz says he struggled to write the film after MGM wanted to shift it to the west coast. He talked to Kunen for a few days then asked himself, "Who is this movie for really? What's the point of this? If it's to preach to the learned already--then it will have no worth"."[3]

Horovitz says "I took the approach that Michael Moore must take with his documentaries. Moore doesn't talk to the people who are already in the know--he's talking to those who don't know. So I started to head in that direction with the re-write of the script."[3]

Irwin Winkler later wrote in his memoirs that Hagman's directorial style, which involved "a great deal of camera movement" meant "the actors sometimes suffered from the crew's allocation of production time versus acting time. But they were game and young, though they required a lot of on-set communication."[10]

"The scenario was cut by the director", said Horovitz, "but not by MGM. It was diluted by cutting – it should have been much stronger than it is. But then it would have lost most of its audience straight away."[11]

The film was shot in Stockton.

Kim Darby says the director "was very kind. He was lenient. He was a lot of fun too. He had done many commercials before, and there was the air of freedom around us."[12]

Music

Thunderclap Newman's Something in the Air is featured on the soundtrack, along with The Circle Game (written by Joni Mitchell) performed by Buffy Sainte-Marie. Plastic Ono Band performs Give Peace A Chance; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young contributed Helpless, Our House, The Loner and Down By The River. Crosby, Stills and Nash perform Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.

Reception

The film was a commercial and critical flop. "The critics attacked the style instead of the substance", said Winkler. "Most disappointing was the dismissal by audiences."[2]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that the film "only lacks an occasional, superimposed written message ... to look like a giant, 103-minute commercial, not for peace, or student activism, or community responsibility, but for the director himself."[13] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and called it "a movie with its heart, if not always its intelligence, in the right place ... The major problem with the film is that during the period before Simon James, a 20-year old student at Western Pacific university, is radicalized, neither his life style as a member of the college crew, nor the political movement on campus is very interesting. Director Stuart Hagman [sic], in his first feature effort, substitutes overly enthusiastic camera techniques and popular music played against the San Francisco scenery for a more complete character definition."[14] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "I found 'The Strawberry Statement' inconsistent and uneven, all too glossy and yet suddenly all too real and populated with children I have no trouble recognizing as my own. And it's the true measure of the film that we are all likely to remember its best moments: The moments when we are made to see the terrible and ironic costs of innocence and idealism."[15] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post stated that the violent climax "would be absurd even if it were well staged, because Hagmann and Horowitz haven't earned their catharsis. There is something howlingly inappropriate about a movie that turns 'angry' after an hour-and-a-half of puppy love, puppy protest and the confectionery audio-visual style pioneered by 'A Man and a Woman' and 'The Graduate.' It's difficult to forget that the script has been fundamentally negligible and incompetent."[16] David Pirie of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "The Strawberry Statement is certain to be attacked for its patchiness and for hollow commercial opportunism; but while students are being killed on university campuses in America, one can't help preferring its highly emotional, if faltering and uneven, tone to the slick reportage of a film like Medium Cool."[17]

Horovitz says when he saw the film "I was really upset with it. I thought it was too cute and Californian and too pretty."[3]

Brian De Palma said "big studio revolutionary movies" like Strawberry were "such a joke. You can't stage that stuff. We've seen it all on television."[18]

"Bad timing", said Davison. "Everyone had enough of the country tearing apart."[19]

Horovitz now says he came to accept the film "for what it is, what it was, and what it represented in the time in which it was made. I'm glad I got to write it."[3]

As a snapshot of its time, the film has collected many present-day fans, as David Sterritt writes for Turner Classic Movies:

Leonard Quart expressed a more measured view in Cineaste, writing that while The Strawberry Statement is basically a "shallow, pop version of the Sixties", it still provides "a taste of the period's dreams and volatility." That's a reasonable take on the film, which is more accurate than it may seem at first glance, depicting an uncertain time when many aspiring rebels were motivated as much by romance and excitement as by principles and ideologies. The Strawberry Statement is a terrific time machine that's also fun to watch.[20]

Awards

The film won the Jury Prize at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, tying with Magasiskola.[21]

In 1971, Bruce Davison was nominated for his performance for the Laurel Awards "Male Star of Tomorrow".

See also

References

- Warga, Wayne (Aug 31, 1969). "Movies: Herbert Solow Strives to Leave His Mark at MGM Herbert Solow and MGM". Los Angeles Times. p. j20.

- Warga, Wayne (May 23, 1971). "Chartoff and Winkler: Interchangeable Producing Partners". Los Angeles Times. p. q1.

- "Interview with Israel Hororvitz". TV Store Online. November 2014.

- A. H. WEILER (May 25, 1969). "And Now the Strawberries of Wrath". New York Times. p. D27.

- Welles, Chris (Aug 3, 1969). "BO POLK AND B SCHOOL MOVIEMAKING". Los Angeles Times. p. l6.

- LEWIS FUNKE (Feb 23, 1969). "Langella -- Shakespeare To Hamlet". New York Times. p. D1.

- ISRAEL HOROVITZ (Aug 16, 1970). "I Didn't Write It for Radicals!". New York Times. p. 89.

- GUY FLATLEY (Sep 27, 1970). "So Truffaut Decided to Work His Own Miracle: So Truffaut Decided to Work His Own Miracle". New York Times. p. X13.

- Kimmis Hendrick (Jan 12, 1970). "Filming a 'couple-week odyssey'". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 6.

- Winkler, Irwin (2019). A Life in Movies: Stories from Fifty Years in Hollywood (Kindle ed.). Abrams Press. p. 488/3917.

- David Sterritt (22 July 1970). "Israel Horovitz: 'I feel a violent revolution coming'". The Christian Science Monitor. p. 11.

- "INTERVIEW SERIES: KIM DARBY talks with TV STORE ONLINE about THE STRAWBERRY STATEMENT". TV Store Online. May 21, 2015.

- Canby, Vincent (June 16, 1970). "Screen: 'Strawberry Statement' Rash of Techniques". The New York Times. 54.

- Siskel, Gene (June 30, 1970). "Strawberry". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 5.

- Champlin, Charles (July 16, 1970). "'Strawberry' Looks at Truth". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 14.

- Arnold, Gary (June 26, 1970). "Strawberry Statement". The Washington Post. D7.

- Pirie, David (July 1970). "The Strawberry Statement". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 37 (438): 142.

- DICK ADLER (Dec 27, 1970). "Hi, Mom, Greetings, It's Brian In Hollywood!". New York Times. p. 64.

- MARTIN KASINDORF (Dec 4, 1977). "I'm Thought of More As an Actor Now Than As a Weirdo'". New York Times. p. 111.

- Sterritt, David. "The Strawberry Statement (1970)". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies (TCM). Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Festival de Cannes: The Strawberry Statement". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-04-11.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Strawberry Statement |