Tomb of the Roaring Lions

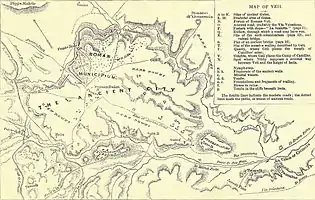

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is an archaeological site at the ancient city of Veii, Italy. It is best known for its well-preserved fresco paintings of four feline-like creatures, believed by archaeologists to depict lions. The tomb is believed to be one of the oldest painted tombs in the western Mediterranean, dating back to 690 BCE . The discovery of the Tomb allowed archaeologists a greater insight into funerary practices amongst the Etruscan people, while providing insight into art movements around this period of time. The fresco paintings on the wall of the tomb are a product of advances in trade that allowed artists in Veii to be exposed to art making practices and styles of drawing originating from different cultures, in particular geometric art movements in Greece.[1] The lions were originally assumed to be caricatures of lions – created by artists who had most likely never seen the real animal in flesh before.[1]

| Tomb of the Roaring Lions | |

|---|---|

| Location | Veii, Italy |

| Built | 690 BCE |

Background

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions was discovered in 2006 in Veii, Italy.[2] As well as the fresco paintings, the tomb was found to contain a number of significant artifacts including urns, brooches and decorated vases. Upon discovery, archaeologists hypothesised that the owner of the tomb was a warrior prince, while the presence of glass bead necklaces suggested the presence of a female occupant in the tomb, whose body has never been found. The notable fresco paintings are located on the rear wall of the tomb.[3] The fresco depicts four feline shapes – three of them are depicted left to right (this is heads facing left, tails facing right) while the fourth is turned towards the other three.[3]

Discovery

The tomb was discovered in 2006, after a tombarolo (illegal excavator) propositioned an Italian court. He was on trial for trafficking hundreds of illegally excavated antiquities. In exchange for a more lenient sentence the tombarolo offered to lead authorities to a previously undiscovered tomb.[2] The court agreed to the unusual offer and the tombarolo lead them to the necropolis of Grotta Gramiccia[3] where previous Etruscan archaeological sites had been unearthed. However, the tombarolo lead them to a unique site where the Tomb of the Roaring Lions was discovered. Archaeologist Alessandro Naso[3] describes the entrance to the tomb,

“The entrance is a long corridor and the door is arched, as is usually the case in Etruscan tomb architecture of the early 7th century BC. The door was still sealed by the original tufa blocks, even though a few on the top had been removed, indicating that the tomb was not intact”.

The tomb was found to be 3.5 metres long and 3.75 metres wide.[3] The entrance wall featured a badly preserved fresco painting of two water birds, however it was the rear wall, depicting the lions that was most notable. Each lion is around 40 cm long.[3] They are painted in black jagged outlines, with prominent, red mouths. Their mouths are open with sharp teeth, as if roaring. The heads are engorged in size in comparison to the rest of the body,[1] while they have large hindlegs and erect, pointed tales. They are depicted in a caricature-like way and are not a realistic portrayal of a lion. Above the lions are two rows of four aquatic birds. While all aquatic birds have been drawn with the same outline, some differences can be distinguished – for example one has wings, while another is depicted with a chequerboard pattern.[3]

Context

The Etruscans were a cultural group who inhabited central Italy from around the 8th to the 3rd century BCE.[4] Unlike other civilisations around the time they were not controlled by a single city or leader, but rather existed as a series of interacting cities[5] with Veii, the city located in close proximity to the Tomb of the Roaring Lions, considered a major hub. The Etruscans are most well known for their art including the wall frescos frequently found within tombs, as well as their terracotta pottery. They were also known for their intense respect for religion. They held strong religious beliefs and were known to practice divination as well as engage in elaborate rituals. The Etruscans were expelled from Rome in 509BCE, while the cities of Veii, Capena, Sutri and Nepet were absorbed by the Roman empire in around 300BCE.[4]

Etruscan Funerary Practices

.jpg.webp)

The Etruscans were highly religious cultural group that held a strong fascination with the afterlife.[5] Consequently, the Etruscans held an intense commitment to funerary traditions. Indeed, Etruscan tombs are so well decorated because of this intense fascination and they believed a notable offering would appease the dead and dissuade them from haunting the living. Burial sites were often located further away from the cities, which explains The Tomb of the Roaring Lions distance from the city of Veii. Like many Etruscan tombs the tomb was constructed from tufa, though often they were carved from natural bedrock. The tomb was also invisible from the surface, as is common amongst Etruscan tombs, however some tombs were marked by a tumulus.

Etruscans had two ways of preparing a body for the tomb. One was cremation, which was the method chosen in the Tomb of the Roaring Lions. In this practice the body is cremated and the ashes then placed into a decorated burial urn. Later on, around 500BCE and during the orientalizing period, inhumation[6] was a practice that the Etruscans used. Inhumation involved wrapping the deceased in a linen cloth and placing the body in a terracotta sarcophagus, before placing the sarcophagus in the tomb. Practices were localised[6] and the method of burial often came down to where the burial was taking place.Tombs were often frescoed with scenes depicting how the deceased lived their life, including particularly enjoyable moments such as banquets or great achievements. They often resembled miniature houses and were furnished and decorated to the extent that a house would be. Tombs were often elaborate and had different rooms, designed to resemble dining rooms and bedrooms. Some tombs, such as the Tomb of Shields and Chairs and the Tomb of the Reliefs, even included beds carved from tufa, stone chairs placed around the tomb and round shields.[6] Other tombs had carvings of household tools and cooking utensils.[6] This demonstrates the Etruscans intense respect for the dead.

Significance of the Paintings

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is particularly notable for its fresco paintings. The figures on the wall of the tomb infer clues as to the identity of the tomb’s occupant, while also demonstrates and reflects artistic movements and practices during this period in history. The tomb depicts four lions and eight aquatic birds – these animals are particularly symbolic when depicted in a burial chamber. Both were regarded by the Etruscan people as spiritual creatures, designed to protect departed souls as they made their journey into the afterlife.[1] Lions in particular were thought to represent a strong, protective force for the deceased, but also symbolised strength and bravery. Lions held particular significance in many ancient cultures. In ancient Greece and Crete lions were thought to be symbols of aristocracy – companions for deceased royalty.[1]

Identity of the deceased

The particular iconography present within the tomb at Veii suggests that the deceased was a child. Lions were known for their sudden fast and ferocious attacks, that often occurred without warning. This swiftness was interpreted by the Etruscan people to symbolise the often sudden and abrupt arrival of death.[1] A child’s death is often particularly sudden. Lions were also considered guardian like creatures, protecting the deceased as they moved into the afterlife.[1] The presence of the birds also suggests that the deceased was young – they were attributed by the Etruscans as mediators between life and the afterlife,[1] believed to symbolise the journey into the afterlife. The position of the birds above the lions in the tomb infers their position as companions to the deceased, designed to together protect and bring the deceased soul to the afterlife. Lions could also have inferred that the deceased was an aristocratic prince who had earned many medals and won many battles before being met by a sudden death.[1] Lions often signified aristocracy and were often symbolised heroes, suggesting that the deceased was successful in life. Koiner[1] notes that in Homer’s the Iliad, “the heroes are compared are compared with strong, savage and murderous animals” reflecting how during this period the strength of lions stood as a symbol of bravery.

Relation to Art Movements

It is highly improbable that the artist who painted the lions in the tomb ever saw a lion in the flesh – while lions were known to inhabit Greece in the Bronze and Iron ages,[1] there is no evidence that lions ever interacted with the Etruscan people. Thus, it is highly likely that the artist copied the depiction of the lion from Greek art. This idea is also supported by the way in which the lions are depicted – they are drawn with sharp lines, oversized heads that are disproportionate to the rest of their bodies and have a geometric, almost triangular shape.[1] This is a reflection of the time in which they were created. The period around 700BCE was known as an orientalizing period in art – trade amongst cultures had exposed artists to new movements and techniques.[1] Veii was in an ideal geographical location to be exposed to these movements - it was located close to the Lower Tiber Valley meaning it could be exposed to both Greek pottery as well as Eastern models,[7] as well as put them in close contact with a variety of other cultural groups. Late geometric attic and Boeotian models were the most likely inspiration for the lions[7] – they arrived around Veii from the trade routes that linked Greece, the Gulf of Naples and Southern Etruria.[7]

Identity of the Artist

Speculation has been made about the artist who painted the famous frescos, however the artist has never been definitively identified. A local artist in Veii around the period was known as the Narce Painter.[1] He painted one of the vases found in the tomb, however he is not believed to have created the famous fresco paintings. The Narce Painter draws his lions in a different way to the frescos – giving them thinner, less protruding tongues.[1] Similarly, images of aquatic birds attributed to the Narce Painter were rendered differently, depicted with ‘long, downwards curved tails.”[1] Thus, it is likely that the Narce Painter was not the creator of the frescos, but rather a contemporary of the man whose art may have mentored or served as inspiration for the fresco painter.

- Koiner, Gabriele (2019). "The Tomb of the Roaring Lions at Veii: Its Relation to Greek Geometric and Early Orientalizing Art". Greek Art in Motion: Studies in Honour of Sir John Boardman on the Occasion of His 90th Birthday: 362 – via JSTOR.

- McMahon, Barbara (18 June 2006). "Italian 'tomb raider' reveals burial chamber". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- Naso, Alessandro (2009). The Origin of Tomb Painting in Etruria. Oxford, United Kingdom. p. 72.

- "Etruscan People". Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Kozlowski, Jane. "Obsession with Death". The Etruscans. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Sheldon, Natasha. "Etruscan Tombs". Ancient History and Archaeology.com. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Tapolli, Jacobo (2019). Veii. University of Texas Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4773-1725-9.

References

- David, Ariel. "Police informant leads the way to 'Tomb of Roaring Lions.'" Associated Press. 17 June 2006.

- Encyclopedia Brittanica, "Etruscan People" Accessed 28 May 2020

- Honeycutt, Jessica “Funerary Practices throughout Civilisations” Ancient Art: University of Alabama https://ancientart.as.ua.edu/funerary-practices-throughout-civilizations/ (Accessed: 24 April 2020)

- Koiner, Gabriele “The Tomb of the Roaring Lions at Veii: Its Relation to Greek Geometric and Early Orientalizing Art” In Greek Art in Motion: Studies in honour of Sir John Boardman on the occasion of his 90th Birthday, edited by Rui Morais, Delfim Leão, Diana Rodríguez Pérez, Daniela Ferreira, (358 – 363), Archaeopress (2019)

- McMahon, Barbara “Italian ‘tomb raider’ reveals burial chamber” The Guardian Last modified: 18 June 2006 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/jun/18/italy.arts

- Merola, Marco “Flights of Fancy: In an early Etruscan tomb, an artist created an exotic bestiary” Archaeology Vol. 59, No. 5Archaeological Institute of America pp. 36–37, 2006

- Met Museum “Geometric Art in Ancient Greece” https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grge/hd_grge.htm (Accessed 24 April 2020)

- Naso, Alessandro Lecture on ‘The Origin of Tomb Painting in Etruria’, speech presented at Oxford, United Kingdom, June 2009

- Sheldon, Natasha, Etruscan Tombs, Ancient History and Archaeology Retrieved from: https://www.ancienthistoryarchaeology.com/etruscan-tombs

- Vermuele, Cornelius ‘Etruscan Leopards and Lions’ Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Vol. 59, No. 315 (13-21), 1961