Treatment of the enslaved in the United States

The treatment of enslaved people in the United States varied by time and place, but was generally brutal, especially on plantations. Whipping and rape were routine, but usually not in front of white outsiders, or even the plantation owner's family. ("When I whip niggers, I take them out of the sight and hearing of the house, and no one in my family knows it."[1]:36) An enslaved person could not be a witness against a white; enslaved people were sometimes required to whip other enslaved people, even family members.[2]:54 There were also businesses to which a slave owner could turn over the whipping.[2]:24[3]:53 Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.[4] There were some relatively enlightened slave owners—Nat Turner said his master was kind[5]—but not on large plantations. Only a small minority of enslaved people received anything resembling decent treatment; one contemporary estimate was 10%, not without noting that the ones well treated desired freedom just as much as those poorly treated.[3]:16, 31 Good treatment could vanish upon the death of an owner. As put by William T. Allan, a slaveowner's abolitionist son who could not safely return to Alabama, "cruelty was the rule, and kindness the exception".[6][7]

| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

There is no known instance in which an enslaved person, having escaped to freedom, returned happily to slavery, or even stated that they were sorry they had fled, because they had been better off enslaved. The United Daughters of the Confederacy, seeking to find a "faithful slave" to erect a monument to, could find no one better than Heyward Shepherd, who was not enslaved, may never have been enslaved, and certainly showed no commitment to or support of slavery.

According to Angelina Grimké, who could not endure the treatment of the enslaved owned by other members of her wealthy family, left Charleston, South Carolina, to become a Quaker abolitionist based in Philadelphia:

I have never seen a happy slave. I have seen him dance in his chains, it is true; but he was not happy. There is a wide difference between happiness and mirth. Man cannot enjoy the former while his manhood is destroyed, and that part of the being which is necessary to the making, and to the enjoyment of happiness, is completely blotted out. The slaves, however, may be, and sometimes are, mirthful. When hope is extinguished, they say, "let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die."[8]

Here is how it was put in 1834 by James Bradley, a formerly enslaved person who, after years of extra work and little sleep, was able to purchase his freedom:

How strange it is that anybody should believe any human being could be a slave, and yet be contented! I do not believe that there ever was a slave, who did not long for liberty. I know very well that slave-owners take a great deal of pains to make the people in the free states believe that the slaves are happy; but I know, likewise, that I was never acquainted with a slave, however well he was treated, who did not long to be free. There is one thing about this, that people in the free states do not understand. When they ask slaves whether they wish for liberty, they answer, "No"; and very likely they will go as far as to say they would not leave their masters for the world. But at the same time, they desire liberty more than anything else, and have perhaps all along been laying plans to get free. The truth is, if a slave shows any discontent, he is sure to be treated worse, and worked harder for it; and every slave knows this. This is why they are careful not to show any uneasiness when white men ask them about freedom. When they are alone by themselves, all their talk is about liberty – liberty! It is the great thought and feeling that fills the minds full all the time.[9]

The same was said by ex-slave Isabella Gibbons, in words engraved on the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers at the University of Virginia.

What is well documented is the eagerness of formerly enslaved men to take up arms against their former owners, first in the British Ethiopian Regiment and Corps of Colonial Marines, then in the United States Colored Troops, even though the Confederacy announced that the latter were traitors and would be immediately shot if captured. There is no instance in which any of these latter soldiers, having obtained arms, used them against Union troops, rather they performed well as Union soldiers.

The Southern picture of slave treatment

In the Antebellum period, the South "claimed before the world" that chattel slavery "was a highly benignant, elevating, and humanizing institution, and as having Divine approbation."[10] The general, quasi-official Southern view of their enslaved was that they were much better off than Northern employed workers, whom Southerners called "wage slaves". Certainly they were much better off than if they were still in Africa, where they did not have Christianity and (allegedly for physiological reasons) their languages had no "abstract terms" like government, vote, or legislature. Slaves loved their masters.[11] Only mental illness could make an enslaved person want to run away, and this supposed malady was given a name, drapetomania.

On occasion of the arrival of "the seditious and insurrectionary proceedings of a Fanatical Society at New-York [the American Anti-Slavery Society], who have presumed to address some of their superstitious, stupid and vile publications to the post office of Frederica" (Georgia), "at a respectable meeting of the Inhabitants" the following statement was prepared:

[O]ur slaves are enjoying the most perfect security and freedom from excessive labor, the most lawless riots and violence, so frequently inflicted on the Blacks of the North....

It is a fact, known to every planter in the South, that our slaves, at some seasons of the year, do not labor half the day to accomplish the work required, while it is a matter of record before the Committee on Ways and Means in Congress, that the laborers in Northern Manufactures are required to work from the earliest dawn of day, to 9 o'clock at night.

The condition of our slaves are [sic] therefore implicitly more independent, comfortable and free, than those over-worked and oppressed laborers, as they are clothed and fed—have as much land as they can cultivate—raise an abundance of poultry, to exchange for the comforts and some of the luxuries of life; and when sick, or the infi[r]mities of a faithful old age secures to them such a freedom as the hypocrits [sic] and fanatics of this abol[i]tion mania will never afford them, their wants are supplied and they are carefully attended in a comfortable Hospital on most plantations; because it is the interest of a master to relieve the sufferings of his slave. It is his pleasure to see them contented. Such are the relations between master and servant, and these vile Abolitionists, these Disunionists and Anarchists would sever [sic], and such are the happy people they wish to cast unprovided for upon a wide and pitiless world!![12]

In a similar statement, "the sufferings of the southern slave dwindle into comparative nothingness" when compared with "the squalid wretchedness, the inhuman oppressions of a large proportion of the white population in the manufacturing districts."[13]

Slavery in the American South was claimed to be the best slavery that had ever existed anywhere:

[W]e...deny that slavery is sinful or inexpedient. We deny that it is wrong in the abstract. We assert that it is the natural condition of man; that there ever has been, and there ever will be slavery; and we not only claim for ourselves the right to determine for ourselves the relations between master and slave, but we insist that the slavery of the Southern States is the best regulation of slavery, whether we take into consideration the interests of the master or of the slave, that has ever been devised.[14]

Southern newspapers regularly ran brief notices of occasional voluntary returnees to slavery, individual cases, although these notes were usually vague anecdotes, second-hand at best; rarely do they mention a name, much less contact the person returning. ("I could cite numerous instances...of slaves returning from the North, from Canada, even from Liberia, voluntarily, into a state of Slavery."[15]) There were some who remained enslaved because manumission would have meant separation from loved ones. Others found such severe and completely legal anti-Black discrimination in employment in the North that they could not earn enough money to live and support a family, so it was slavery or starvation.

Sources on American treatment of slaves

Rankin's Letters on Slavery (1826)

Religion is at the center of American abolitionism. Just as Quakers had been early leaders against slavery, it was now Presbyterians, at the time one of the largest denominations in the country, who felt called to do God's will: to end the sin of enslaving another human being. There was considerable writing on the question of whether the Bible does or does not approve of slavery.[16]

Starting with Presbyterian minister John Rankin's 1826 Letters on Slavery, which began as letters to his brother who had acquired slaves, readers began to hear about slavery as the slaves experienced it. Rankin lived in Ripley, Ohio, on the Ohio River. There were many fugitive slaves crossing the river separating slave Kentucky from free Ohio; they provided Rankin plenty of information. "His home became one of the busiest stations on the underground railroad in the Ohio Valley."[17]:161 His "house atop the hill in Ripley has remained the Underground Railroad's most famous landmark."[18]:4 There is a lot of confusion about the "real" Eliza of Uncle Tom's Cabin, but she passed through Rankin's house.[18] Harriet Beecher Stowe, living nearby in Cincinnati, and Rankin knew each other. One source says that Stowe met the "real" Eliza in Rankin's house.[19]

- Rankin first pointed out that blacks were not "racially" inferior. "The organization of their mental powers is equal to that of the rest of mankind."[20]:14 "Many of the Africans possess the finest powers of mind, and...in this respect, they are naturally equal to the rest of mankind."[20]:29

- Rankin went on to present the depressing conditions of life as a slave: "As the making of grain is the main object of their emancipation, masters will sacrifice as little as possible in giving them food. It often happens that what will barely keep them alive, is all that a cruel avarice will allow them. Hence, in some instances, their allowance has been reduced to a single pint of corn each during the day and night. And some have no better allowance than a small portion of cotton seed!! And in some places the best allowance is a peck of corn each during the week, while perhaps they are not permitted to taste meat so much as once in the course of seven years, except what little they may be able to steal! Thousands of them are pressed with the gnawings of cruel hunger during their whole lives — an insatiable avarice will not grant them a single comfortable meal to satisfy the cravings of nature! Such cruelty far exceeds the powers of description! ...Thousands of them are really starving in a state of slavery, and are under the direful necessity of stealing whatever they can find, that will satisfy the cravings of hunger; and I have little doubt but many actually starve to death."[20]:37–38

- "[I]n some parts of Alabama, you may see slaves in the cotton fields without so much as even a single rag upon them, shivering before the chilling blasts of mid-winter. ...Indeed in every slaveholding state many slaves suffer extremely, both while they labor and while they sleep, for want of clothing to keep them warm. Often they are driven through frost and snow without either stocking or shoe until the path they tread is dyed with the blood that issues from their frost-worn limbs! And when they return to their miserable huts at night they find not there the means of comfortable rest; but on the cold ground they must lie without covering, and shiver, while they slumber."[20]:36–37

- "The slaveholder has it in his power, to violate the chastity of his slaves. And not a few are beastly enough to exercise such power. Hence it happens that, in some families, it is difficult to distinguish the free children from the slaves. It is sometimes the case, that the largest part of the master's own children are born, not of his wife, but of the wives and daughters of his slaves, whom he has basely prostituted as well as enslaved."[20]:38 (See Children of the plantation.)

- "Among the rest was an ill grown boy about seventeen, who having just returned from a skulking spell, was sent to the spring for water, and in returning let fall an elegant pitcher. It was dashed to shivers upon the rocks. This was the occasion. It was night, and the slaves all at home. The master had them collected into the most roomy negrohouse, and a rousing fire made. When the door was secured, that none might escape, either through fear of him or sympathy with George, he opened the design of the interview, namely, that they might be effectually taught to stay at home and obey his orders. All things being now in train, he called up George, who approached his master with the most unreserved submission. He bound him with cords, and by the assistance of his younger brother, laid him on a broad bench, or meat block. He now proceeded to whang [small capitals in the original] off George by the ancles!!! It was with the broad ax! — In vain did the unhappy victim scream and roar! He was completely in his master's power. Not a hand amongst so many durst interfere. Casting the feet into the fire, he lectured them at some length. He whacked him off below the knees! George roaring out, and praying his master to begin at the other end! He admonished them again, throwing the legs into the fire! Then above the knees, tossing the joints into the fire! He again lectured them at leisure. The next stroke severed the thighs from the body. These were also committed to the flames. And so off the arms, head and trunk, until all was in the fire! Still protracting the intervals with lectures, and threatenings of like punishment, in case of disobedience, or running away. ...He said that he had never enjoyed himself at a ball so well as he had enjoyed himself that evening."[20]:63–64

There was only one edition of these letters before 1833 (and the warehouse with unsold copies "was set on fire and burned to the ground"[20]:161). Wm. Lloyd Garrison, who was America's leading abolitionist in the 1830s, spoke of the influence of Rankin's Letters on him. He reprinted the then-obscure book in full in his newspaper The Liberator starting on August 25, 1832. He and his collaborator Isaac Knapp promptly issued it in book form as Letters on American Slavery (1833), reprinted in 1836 and 1838, becoming common reading for abolitionists.

Slavery...in the United States (1834)

Another collection of incidents of mistreatment of slaves appeared in 1834, from an otherwise unknown E. Thomas, under the title A concise view of the slavery of the people of color in the United States; exhibiting some of the most affecting cases of cruel and barbarous treatment of the slaves by their most inhuman and brutal masters; not heretofore published: and also showing the absolute necessity for the most speedy abolition of slavery, with an endeavor to point out the best means of effecting it. To which is added, A short address to the free people of color. With a selection of hymns, &c. &c.

In his preface, Thomas explains: "[M]y principal design at present, is, to record some striking cases of cruelty of more recent date, not heretofore published, and which have been related to me during my travels through the different states, for three years past: in order to excite in the mind of every individual a love of liberty, and an inveterate abhorrence of slavery, that each may endeavor by throwing in his mite, to contribute towards its total abolition. ...Those facts or accounts of cruelty have been communicated to me by different persons of undoubted veracity, and in whom I place the most entire confidence."[21]

Chapter titles in this collection include:

- The infant whipped to death with a cow-skin, . 8 [cow skins were a frequent whipping tool[3]:60[22]:4]

- The aged woman starved to death, . . 9

- The man that had his teeth knocked out, . . 11

- The slave shot by her master, . . 18

- The slave that was shot for going out to preach, 20

- The slave whipped for hard riding, . . 22

- Slaves eating out of a hog-trough, . . 23

- The slave whipped to death for killing a sheep, 24

- The slave slowly dissected and burnt, . . 25

- The slave whipped to death for telling his vision, 27

- The man and wife yoked like oxen, . . 29

- The slave whipped for going to see his wife, . 38

- The slave flogged and robbed, . . .39

The publications of the anti-slavery societies

Starting in the early 1830s there were dozens of lecturers, many of them trained as ministers, criss-crossing the free states, speaking and giving lectures in churches, meeting-houses, and any other venue that would have them, on how slaves were treated in the American South. There was even training for these lecturers, in Ohio, by Theodore Dwight Weld, employed by an anti-slavery society. Hundreds of local anti-slavery societies were formed. What little publicity these lectures got was mostly negative, but in the publications of the larger anti-slavery societies we have considerable information on what they were saying, across the North, about the treatment of American slaves.

A female slave was sent on an errand, and was gone longer than her master wished. She was ordered to be flogged, and was tied up and nearly beaten to death. While the overseer was whipping her, in the presence of her master, she said that she had been prevented returning sooner by sickness on the way. Her enraged master ordered her to be whipped again for daring to speak, and the lash was again applied, until she expired under the operation. Nor was her life alone sacrificed. An unborn infant died with her, which had been the cause of her delay on her master's errand. Another case occurred, where a black boy was whipped for stealing a piece of leather, and because he persisted in denying it, he was whipped till he died. After he was dead, his master's son acknowledged that he took the piece of leather. A Georgian bought five slaves and set them a task in the field, which they could not or would not do. The next day he added another task, with orders that they should do that and the work of the preceding day, or be whipped until they accomplished it. The third day more work was added and additional whipping ordered. The work was now beyond the strength of the slaves. They tried in vain to accomplish it, and at last left it in despair, and went into the woods. They were missed, and pursuit made after them, and were all found hanging dead. They had committed suicide to escape the cruelty of their master. A hole was dug, and they were thrown into it, amid the curses of their owner at the loss he had met with in his property.[23]:58

A slave, who was a husband and father, was made to strip his wife and daughter, and whip them.[24]

A similar report was published by Garrison in the July 3, 1862 issue of The Liberator.[25]

American Slavery As It Is (1839)

Although there were a variety of books in which travelers in the South reported what they saw and heard about the enslaved,[3][1] the encyclopedia of the cruelty with which American slaves were treated was American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, by Theodore Dwight Weld, his wife Angelina Grimké, and her sister Sarah Grimké, which was published in 1839 by the American Anti-Slavery Society. Well organized, by informant and by topic (Food, Labor, Dwellings, Clothing, Treatment of the Sick, Privations, Punishments, Tortures), it states at the outset that most of the stories are taken from Southern newspapers, most of which are available at the office of the publisher, the American Anti-Slavery Society, 143 Nassau St., New York, and invites the public to call and see their sources. Over 6 to 24 months, Weld had purchased in bulk thousands of issues of papers being discarded by a reading room at the New York Stock Exchange (open to white men only), then taken them home to Fort Lee, New Jersey, where the Grimké sisters analyzed them.[26]:97 The names of informants are given, but "a number of them still reside in slave states; — to publish their names would be, in most cases, to make them the victims of popular fury."[2]

Here is a statement by Theodore Weld about what the book contains:

Reader, you are impaneled as a juror to try a plain case and bring in an honest verdict. The question at issue is not one of law, but of fact — "What is the actual condition of the slaves in the United States? ...As slaveholders and their apologists are volunteer witnesses in their own cause, and are flooding the world with testimony that their slaves are kindly treated; that they are well fed, well clothed, well housed, well lodged, moderately worked, and bountifully provided with all things needful for their comfort, we propose — first, to disprove their assertions by the testimony of a multitude of impartial witnesses.... We will prove that the slaves in the United States are treated with barbarous inhumanity; that they are overworked, underfed, wretchedly clad and lodged, and have insufficient sleep; that they are often made to wear round their necks iron collars armed with prongs, to drag heavy chains and weights at their feet while working in the field, and to wear yokes, and bells, and iron horns; that they are often kept confined in the stocks day and night for weeks together, made to wear gags in their mouths for hours or days, have some of their front teeth torn out or broken off, that they may be easily detected when they run away; that they are frequently flogged with terrible severity, have red pepper rubbed into their lacerated flesh, and hot brine, spirits of turpentine, &c., poured over the gashes to increase the torture; that they are often stripped naked, their backs and limbs cut with knives, bruised and mangled by scores and hundreds of blows with the paddle, and terribly torn by the claws of cats, drawn over them by their tormentors; that they are often hunted with blood hounds and shot down like beasts, or torn in pieces by dogs; that they are often suspended by the arms and whipped and beaten till they faint, and when revived by restoratives, beaten again till they faint, and sometimes till they die; that their ears are often cut off, their eyes knocked out, their bones broken, their flesh branded with red hot irons; that they are maimed, mutilated and burned to death over slow fires. All these things, and more, and worse, we shall prove. Reader, we know whereof we affirm, we have weighed it well; more and worse WE WILL PROVE. Mark these words, and read on; we will establish all these facts by the testimony of scores and hundreds of eyewitnesses, by the testimony of slaveholders in all parts of the slave states, by slaveholding members of Congress and of state legislatures, by ambassadors to foreign courts, by judges, by doctors of divinity, and clergymen of all denominations, by merchants, mechanics, lawyers and physicians, by presidents and professors in colleges and professional seminaries, by planters, overseers and drivers. We shall show, not merely that such deeds are committed, but that they are frequent; not done in corners, but before the sun; not in one of the slave states, but in all of them; not perpetrated by brutal overseers and drivers merely, but by magistrates, by legislators, by professors of religion, by preachers of the gospel, by governors of states, by "gentlemen of property and standing," and by delicate females moving in the "highest circles of society."[2]:9

In a measure unusual at the time, the book concluded with an index, allowing the reader to quickly locate information by person or newspaper, and by type of treatment.

Slave narratives and lectures

As there began to be a significant number of literate ex-slaves (freedmen or fugitives), some wrote of their earlier experiences as slaves, reporting mistreatment they witnessed and suffered themselves. Shortly after, a growing number of former slaves were able to speak in public, sometimes eloquently, about what they had experienced and seen. Starting with James Bradley, in Ohio, then William G. Allen, so well-educated that he taught Greek at New-York Central College, in Massachusetts and upstate New York, Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth across the free states, and the list could be extended. Both the slave narratives and the lectures were for free state audiences, who were mostly naware of the reality of enslaved peole's lives.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass published in 1845 his autobiography, which became a bestseller. The following is from that work:

His cruelty and meanness were especially displayed in his treatment of my unfortunate cousin Henny, whose lameness made her a burden to him. I have seen him tie up this lame and maimed woman and whip her in a manner most brutal and shocking; and then with blood-chilling blasphemy he would quote the passage of scripture, 'That servant which knew his lord's will and prepared not himself, neither did according to his will, shall be beaten with many stripes.' He would keep this lacerated woman tied up by her wrists to a bolt in the joist, three, four, and five hours at a time. He would tie her up early in the morning, whip her with a cowskin before breakfast, leave her tied up, go to his store, and returning to dinner repeat the castigation, laying on the rugged lash on flesh already raw by repeated blows. He seemed desirous to get the poor girl out of existence, or at any rate off his hands. ...Finally, upon a pretense that he could do nothing for her (I use his own words), he 'set her adrift to take care of herself' ...turning loose the only cripple among [his slaves] virtually to starve and die."[27]

At an earlier autobiography, he describes the cowskin whip:

The cowskin is a kind of whip seldom seen in the northern states. It is made entirely of untanned, but dried, ox hide, and is about as hard as a piece of well-seasoned live oak. It is made of various sizes, but the usual length is about three feet. The part held in the hand is nearly an inch in thickness; and, from the extreme end of the butt or handle, the cowskin tapers its whole length to a point. This makes it quite elastic and springy. A blow with it, on the hardest back, will gash the flesh, and make the blood start. Cowskins are painted red, blue and green, and are the favorite slave whip. I think this whip worse than the "cat-o'nine-tails." It condenses the whole strength of the arm to a single point, and comes with a spring that makes the air whistle. It is a terrible instrument, and is so handy, that the overseer can always have it on his person, and ready for use. The temptation to use it is ever strong; and an overseer can, if disposed, always have cause for using it. With him, it is literally a word and a blow, and, in most cases, the blow comes first.[28]

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth, to whose narrative the above statement by Douglas was appended, relates the following scene she witnessed:

...one Hasbrouck. — He had a sick slave-woman, who was lingering with a slow consumption [tuberculosis] whom he made to spin, regardless of her weakness and suffering; and this woman had a child, that was unable to walk or talk, at the age of five years, neither could it cry like other children, but made a constant, piteous, moaning sound. This exhibition of helplessness and imbecility, instead of exciting the master's pity, stung his cupidity, and so enraged him, that he would kick the poor thing about like a foot-ball. Isabella's informant had seen this brute of a man, when the child was curled up under a chair, innocently amusing itself with a few sticks, drag it thence, that he might have the pleasure of tormenting it. She had seen him, with one blow of his foot, send it rolling quite across the room, and down the steps at the door. Oh, how she wished it might instantly die! "But," she said, "it seemed as tough as a moccasin." Though it did die at last, and made glad the heart of its friends; and its persecutor, no doubt, rejoiced with them, but from very different motives.[29]:83

Teaching slaves to read was discouraged or (depending upon the state) prohibited, so as to hinder aspirations for escape or rebellion. In response to slave rebellions such as the Haitian Revolution, the 1811 German Coast Uprising, a failed uprising in 1822 organized by Denmark Vesey, and Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831, some states prohibited slaves from holding religious gatherings, or any other kind of gathering, without a white person present, for fear that such meetings could facilitate communication and lead to rebellion and escapes.

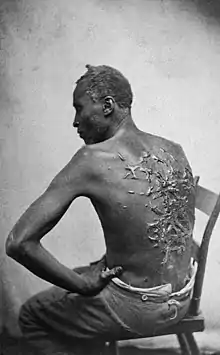

Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, beating, mutilation, branding, and/or imprisonment. Punishment was most often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but masters or overseers sometimes abused slaves to assert dominance. Pregnancy was not a barrier to punishment; methods were devised to administer lashings without harming the baby. Slave masters would dig a hole big enough for the woman's stomach to lie in and proceed with the lashings.[30] But such "protective" steps gave neither expectant slave mothers nor their unborn infants much real protection against grave injury or death from excess zeal or number of lashes inflicted, as one quote by ex-captive Moses Grandy took note:

One of my sisters was so severely punished in this way, that labour was brought on, and the child born in the field. This very overseer, Mr. Brooks, killed in this manner a girl named Mary: her [parents] were in the field at the time. He also killed a boy about twelve years old. He had no punishment, or even trial, for either [murder].[31]

The mistreatment of slaves frequently included rape and the sexual abuse of women. The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in historical Southern culture and its view of the enslaved as property.[32] After 1662, when Virginia adopted the legal doctrine partus sequitur ventrem, sexual relations between white men and black women were regulated by classifying children of slave mothers as slaves regardless of their father's race or status. Particularly in the Upper South, a population developed of mixed-race (mulatto) offspring of such unions (see children of the plantation), although white Southern society claimed to abhor miscegenation and punished sexual relations between white women and black men as damaging to racial purity.

Frederick Law Olmsted visited Mississippi in 1853 and wrote:

A cast mass of the slaves pass their lives, from the moment they are able to go afield in the picking season till they drop worn out in the grave, in incessant labor, in all sorts of weather, at all seasons of the year, without any other change or relaxation than is furnished by sickness, without the smallest hope of any improvement either in their condition, in their food, or in their clothing, which are of the plainest and coarsest kind, and indebted solely to the forbearance or good temper of the overseer for exception from terrible physical suffering.[33]

Living conditions

Compiling a variety of historical sources, historian Kenneth M. Stampp identified in his classic work The Peculiar Institution reoccurring themes in slavemasters’ efforts to produce the "ideal slave":

- Maintain strict discipline and unconditional submission.

- Create a sense of personal inferiority, so that slaves "know their place."

- Instill fear.

- Teach servants to take interest in their master's enterprise.

- Prevent access to education and recreation, to ensure that slaves remain uneducated, helpless, and dependent.[34][35]

Brutality

According to historians David Brion Davis and Eugene Genovese, treatment of slaves was harsh and inhumane. During work and outside of it, slaves suffered physical abuse, since the government allowed it. Treatment was usually harsher on large plantations, which were often managed by overseers and owned by absentee slaveholders. Small slaveholders worked together with their slaves and sometimes treated them more humanely.[36]

Besides slaves' being vastly overworked, they suffered brandings, shootings, "floggings," and much worse punishments. Flogging was a term often used to describe the average lashing or whipping a slave would receive for misbehaving. Many times a slave would also simply be put through "wanton cruelties" or unprovoked violent beatings or punishments.[37]

Inhumane treatment

After 1820,[38] in response to the inability to legally import new slaves from Africa following prohibition of the international slave trade, some slaveholders improved the living conditions of their slaves, to influence them not to attempt escape.[39]

Some slavery advocates asserted that many slaves were content with their situation. African-American abolitionist J. Sella Martin countered that apparent "contentment" was in fact a psychological defense to dehumanizing brutality of having to bear witness to their spouses being sold at auction and daughters raped.[40] Likewise, Elizabeth Keckley, who grew up a slave in Virginia and became Mary Todd Lincoln's personal modiste, gave an account of what she had witnessed as a child to explain the folly of any claim that the slave was jolly or content. Little Joe, son of the cook, was sold to pay his owner's bad debt:

Joe’s mother was ordered to dress him in his best Sunday clothes and send him to the house, where he was sold, like the hogs, at so much per pound. When her son started for Petersburgh, ... she pleaded piteously that her boy not be taken from her; but master quieted her by telling that he was going to town with the wagon, and would be back in the morning. Morning came, but little Joe did not return to his mother. Morning after morning passed, and the mother went down to the grave without ever seeing her child again. One day she was whipped for grieving for her lost boy.... Burwell never liked to see his slaves wear a sorrowful face, and those who offended in this way were always punished. Alas! the sunny face of the slave is not always an indication of sunshine in the heart.[41]

William Dunway notes that slaves were often punished for their failure to demonstrate due deference and submission to whites. Demonstrating politeness and humility showed the slave was submitting to the established racial and social order, while failure to follow them demonstrated insolence and a threat to the social hierarchy. Dunway observes that slaves were punished almost as often for symbolic violations of the social order as they were for physical failures; in Appalachia, two-thirds of whippings were done for social offences versus one-third for physical offences such as low productivity or property losses.[42]

Education and access to information

Slave owners, even though they proclaimed American slavery to be benevolent, greatly feared slave rebellions.[43] Most of them sought to minimize slaves' exposure to the outside world to reduce the risk. The desired result was to eliminate slaves' dreams and aspirations, restrict access to information about escaped slaves and rebellions, and stifle their mental faculties.[39]

Education of slaves, then, was at least discouraged, and usually prohibited altogether. (See Education during the slave period.) It was seen by slaveowners as something the enslaved, like other farm animals, did not need to do their jobs. They believed slaves with knowledge would become morose, if not insolent and "uppity". They might learn of the Underground Railroad: that escape was possible, that many would help, and that there were sizeable communities of formerly enslaved Blacks in Northern cities.[44]

In 1841, Virginia punished violations of this law by 20 lashes to the slave and a $100 fine to the teacher, and North Carolina by 39 lashes to the slave and a $250 fine to the teacher.[44] In Kentucky, education of slaves was legal but almost nonexistent.[44] Some Missouri slaveholders educated their slaves or permitted them to do so themselves.[45] In Utah, slave owners were required to send black slaves to school for eighteen months between the ages of six and twenty years[46] and Indian slaves for three months every year.[47]

Working conditions

In 1740, following the Stono Rebellion, Maryland limited slaves' working hours to 15 per day in the summer and 14 in the winter, with no work permitted on Sunday. Historian Charles Johnson writes that such laws were not only motivated by compassion, but also by the desire to pacify slaves and prevent future revolts. Slave working conditions were often made worse by the plantation's need for them to work overtime to sustain themselves in regards to food and shelter.[48][49] In Utah, slaves were required to work "reasonable" hours.[46]

Child workers

Children, who of course could not go to school, were, like adults, usually expected to work to their physical limits. It was completely legal to exploit children, to work them brutally, to whip them, and to use them sexually. Even very young children could be given tasks such as guarding flocks or carrying water to the field hands.

Medical treatment

The quality of medical care to slaves is uncertain; some historians conclude that because slaveholders wished to preserve the value of their slaves, they received the same care as whites did. Others conclude that medical care was poor. A majority of plantation owners and doctors balanced a plantation need to coerce as much labor as possible from a slave without causing death, infertility, or a reduction in productivity; the effort by planters and doctors to provide sufficient living resources that enabled their slaves to remain productive and bear many children; the impact of diseases and injury on the social stability of slave communities; the extent to which illness and mortality of sub-populations in slave society reflected their different environmental exposures and living circumstances rather than their alleged racial characteristics.[50] Slaves may have also provided adequate medical care to each other.[51] Previous studies show that a slave-owner would care for his slaves through only "prudence and humanity." Although conditions were harsh for most slaves, many slave-owners saw that it was in their best interest financially to see that each slave stayed healthy enough to maintain an active presence on the plantation, and if female, to reproduce. (In the northern states of Maryland and Virginia, children were openly spoken of as a "product" exported to the Deep South.) An ill slave meant less work done, and that motivated some plantation owners to have medical doctors monitor their slaves in an attempt to keep them healthy. (J. Marion Sims was for some years a "plantation doctor".) Other slave-owners wishing to save money would rely on their own self-taught remedies, combined with any helpful knowledge of their wives to help treat the sickly. Older slaves and oftentimes grandparents of slave communities would pass down useful medical skills and remedies as well. Also, large enough plantations with owners willing to spend the money would often have primitive infirmaries built to deal with the problems of slaves' health.[52]

According to Michael W. Byrd, a dual system of medical care provided poorer care for slaves throughout the South, and slaves were excluded from proper, formal medical training.[53] This meant that slaves were mainly responsible for their own care, a "health subsystem" that persisted long after slavery was abolished.[54] Slaves took such an active role in the health care of their community. In 1748, Virginia prohibited them from advertising certain treatments.[55]

Medical care was usually provided by fellow slaves or by slaveholders and their families, and only rarely by physicians.[56] Care for sick household members was mostly provided by women. Some slaves possessed medical skills, such as knowledge of herbal remedies and midwifery and often treated both slaves and non-slaves.[57] Covey suggests that because slaveholders offered poor treatment, slaves relied on African remedies and adapted them to North American plants.[55] Other examples of improvised health care methods included folk healers, grandmother midwives, and social networks such as churches, and, for pregnant slaves, female networks. Slave-owners would sometimes also seek healing from such methods in times of ill health.[58] In Missouri, slaveholders generally provided adequate health care to their slaves, and were motivated by humanitarian concerns, maintenance of slaves' productivity, and protection of the owners' investment.[57]

Researchers performed medical experiments on slaves, who could not refuse, if their owners permitted it. They frequently displayed slaves to illustrate medical conditions.[59] Southern medical schools advertised the ready supply of corpses of the enslaved, for dissection in anatomy classes, as an incentive to enroll.[60]:183–184

Religion

During the early 17th century, some colonies permitted slaves who converted to Christianity to become free, but this possibility was eliminated by the mid 17th century.[61]

In 1725, Virginia granted slaves the right to establish a church, leading to the establishment of the First Church of Colored Baptists.[62] In many cases throughout the American South, slaves created hybrid forms of Christianity, mixing elements of traditional African religions with traditional as well as new interpretations of Christianity.[63]

South Carolina permitted law enforcement to disband any religious meeting where more than half the participants were black.[64]

Earnings and possessions

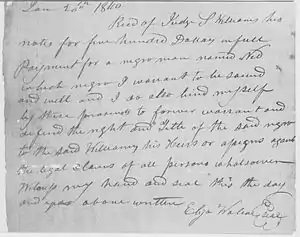

Owners usually provided the enslaved with low-quality clothing, made from rough cloth and shoes from old leather.[65] Masters commonly paid slaves small bonuses at Christmas, and some slaveholders permitted them to keep earnings and gambling profits. One slave, Denmark Vesey, bought his freedom with a lottery prize;[66] James Bradley worked extra hours and was allowed to save enough to purchase his.

In comparison to non-slaves

Robert Fogel argued that the material conditions of slaves were better than those of free industrial workers. However, 58% of historians and 42% of economists surveyed disagreed with Fogel's proposition.[67] Fogel's view was that, while slaves' living conditions were poor by modern standards, all workers during the first half of the 19th century were subject to hardship. He further stated that over the course of their lifetime, a typical slave field hand "received" about 90% of the income he produced.[67]

Slaves were legally considered non-persons unless they committed a crime. An Alabama court ruled that slaves "are rational beings, they are capable of committing crimes; and in reference to acts which are crimes, are regarded as persons. Because they are slaves, they are incapable of performing civil acts, and, in reference to all such, they are things, not persons."[68]

Punishment and abuse

Slaves were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding, rape, and imprisonment. Punishment was often meted out in response to disobedience or perceived infractions, but sometimes abuse was performed to re-assert the dominance of the master (or overseer) over the slave.[69] They were punished with knives, guns, field tools and nearby objects. The whip was the most common instrument used against a slave; one said "The only punishment that I ever heard or knew of being administered slaves was whipping", although he knew several who were beaten to death for offenses such as "sassing" a white person, hitting another "negro", "fussing" or fighting in quarters.[70]

Slaves who worked and lived on plantations were the most frequently punished. Punishment could be administered by the plantation owner or master, his wife, children, or (most often) the overseer or driver.

Slave overseers were authorized to whip and punish slaves. One overseer told a visitor, "Some Negroes are determined never to let a white man whip them and will resist you, when you attempt it; of course you must kill them in that case."[71] A former slave describes witnessing females being whipped: "They usually screamed and prayed, though a few never made a sound."[72] If the woman was pregnant, workers might dig a hole for her to rest her belly while being whipped. After slaves were whipped, overseers might order their wounds be burst and rubbed with turpentine and red pepper. An overseer reportedly took a brick, ground it into a powder, mixed it with lard and rubbed it all over a slave.[70]

A metal collar could be put on a slave. Such collars were thick and heavy; they often had protruding spikes which made fieldwork difficult and prevented the slave from sleeping when lying down. Louis Cain, a former slave, describes seeing another slave punished: "One nigger run to the woods to be a jungle nigger, but massa cotched him with the dog and took a hot iron and brands him. Then he put a bell on him, in a wooden frame what slip over the shoulders and under the arms. He made that nigger wear the bell a year and took it off on Christmas for a present to him. It sho' did make a good nigger out of him."[70]

Slaves were punished for a number of reasons: working too slowly, breaking a law (for example, running away), leaving the plantation without permission, insubordination, impudence as defined by the owner or overseer, or for no reason, to underscore a threat or to assert the owner's dominance and masculinity. Myers and Massy describe the practices: "The punishment of deviant slaves was decentralized, based on plantations, and crafted so as not to impede their value as laborers."[73] Whites punished slaves publicly to set an example. A man named Harding describes an incident in which a woman assisted several men in a minor rebellion: "The women he hoisted up by the thumbs, whipp'd and slashed her [sic] with knives before the other slaves till she died."[74] Men and women were sometimes punished differently; according to the 1789 report of the Virginia Committee of the Privy Council, males were often shackled but women and girls were left free.[74]

The branding of slaves for identification was common during the colonial era; however, by the nineteenth century it was used primarily as punishment. Mutilation of slaves, such as castration of males, removing a front tooth or teeth, and amputation of ears was a relatively common punishment during the colonial era, still used in 1830: it facilitated their identification if they ran away. Any punishment was permitted for runaway slaves, and many bore wounds from shotgun blasts or dog bites used by their captors.[75]

In 1717, Maryland law provided that slaves were not entitled to a jury trial for a misdemeanor and empowered county judges to impose a punishment of up to 40 lashes.[76] In 1729, the colony passed a law permitting punishment for slaves including hanging, decapitation, and cutting the body into four quarters for public display.[62]

In 1740, South Carolina passed a law prohibiting cruelty to slaves; however, slaves could still be killed under some circumstances. The anti-cruelty law prohibited cutting out the tongue, putting out the eye, castration, scalding, burning, and amputating limbs, but permitted whipping, beating, putting in irons, and imprisonment.[77] There was almost no enforcement of the prohibitions, as a slave could not be a witness nor give testimony against a white.[78]

In 1852, Utah passed the Act in Relation to Service, which provided several protections for slaves. They were freed if the slave owner was found guilty of cruelty or abuse, or neglect to feed, clothe, or shelter the slave, or if there were any sexual intercourse between the master and the slave.[79] The definition of cruelty was vague and hard to enforce, and in practice, slaves received similar treatment to those in the South.[80]

Laws governing treatment

By law, slaveholders could be fined for not punishing recaptured runaway slaves. Slave codes authorized, indemnified or required violence, and were denounced by abolitionists for their brutality.[81][82] Both slaves and free blacks were regulated by the Black Codes, and their movements were monitored by slave patrols conscripted from the white population. The patrols were authorized to use summary punishment against escapees; in the process, they sometimes maimed or killed the escapees.

.jpg.webp)

Historian Nell Irvin Painter and others have documented that Southern history went "across the color line." Contemporary accounts by Mary Chesnut and Fanny Kemble (both married in the Deep South planter class) and accounts by former slaves gathered by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) attested to the abuse of women slaves by white owners and overseers.

Slave codes

The slave-owning colonies had laws governing the control and punishment of slaves which were known as slave codes.[83] South Carolina established its slave code in 1712, based on the 1688 Barbadian slave code. The South Carolina slave code was a model for other North American colonies. In 1770, Georgia adopted the South Carolina slave code and Florida adopted the Georgia code.[83] The 1712 South Carolina slave code included the following provisions:[83]

- Slaves were forbidden to leave the owner's property unless accompanied by a white person, or with permission. If a slave left the owner's property without permission, "every white person" was required to chastise them.

- Any slave attempting to run away and leave the colony (later, the state) received the death penalty.

- Any slave who evaded capture for 20 days or more was to be publicly whipped for the first offense; branded with an "R" on the right cheek on the second offense; lose one ear if absent for thirty days on the third offense, and castrated on the fourth offense.

- Owners refusing to abide by the slave code were fined and forfeited their slaves.

- Slave homes were searched every two weeks for weapons or stolen goods. Punishment escalated from loss of an ear, branding and nose-slitting to death on the fourth offense.

- No slave could work for pay; plant corn, peas or rice; keep hogs, cattle, or horses; own or operate a boat; buy or sell, or wear clothes finer than "Negro cloth".

The South Carolina slave code was revised in 1739, with the following amendments:[83]

- No slave could be taught to write, work on Sunday, or work more than 15 hours per day in summer and 14 hours in winter.

- The willful killing of a slave was fined £700, and "passion" killing £350.

- The fine for concealing runaway slaves was $1,000 and a prison sentence up to one year.

- A fine of $100 and six months in prison were imposed for employing a freeman or slave as a clerk.

- A fine of $100 and six months in prison were imposed for selling (or giving) alcoholic beverages to slaves.

- A fine of $100 and six months in prison were imposed for teaching a slave to read and write; the death penalty was imposed for circulating incendiary literature.

- Freeing a slave was forbidden except by deed (after 1820, only by permission of the legislature; Georgia required legislative approval after 1801).

The slave codes in the tobacco colonies (Delaware, Maryland, North Carolina and Virginia) were modeled on the Virginia code, established in 1667.[83] The 1682 Virginia code included the following provisions:[84]:19

- Slaves were prohibited from possessing weapons.

- Slaves were prohibited from leaving their owner's plantation without permission.

- Slaves were prohibited from attacking a white person, even in self-defense.

- A runaway slave, refusing to surrender, could be killed without penalty.

Owners convicted of crimes

In 1811, Arthur William Hodge was the first slaveholder executed for the murder of a slave in the British West Indies. However, he was not (as some have claimed) the first white person to have been executed for killing a slave.[85] Records indicate at least two earlier incidents. On November 23, 1739, in Williamsburg, Virginia, two white men (Charles Quin and David White) were hanged for the murder of another white man's slave. On April 21, 1775, the Virginia Gazette in Fredericksburg reported that a white man (William Pitman) was hanged for the murder of his own slave.[86]

Laws punishing whites for punishing their slaves were weakly enforced or easily avoided. In Smith v. Hancock, the defendant justified punishing his slave to a white jury; the slave was attending an unlawful meeting, discussed rebellion, refused to surrender and resisted the arresting officer by force.[87]

Sexual relations and rape

Rape and sexual abuse

Owners of slaves could legally use them as sexual objects. Therefore, slavery in the United States encompassed wide-ranging rape and sexual abuse, including many unwanted pregnancies.[32] Many slaves fought back against sexual attacks, and some died resisting them; others were left with psychological and physical scars.[88] "Soul murder, the feeling of anger, depression and low self-esteem" is how historian Nell Irvin Painter describes the effects of this abuse, linking it to slavery. Slaves regularly suppressed anger before their masters to avoid showing weakness.

Harriet Jacobs said in her narrative that she believed her mistress did not try to protect her because she was jealous of her master's sexual interest in her. Victims of abuse during slavery may have blamed themselves for the incidents, due to their isolation.{[89]}

Rape laws in the South embodied a race-based double standard. Black men accused of rape during the colonial period were often punished with castration, and the penalty was increased to death during the Antebellum Period;[90] however, white men could legally rape their female slaves.[90] Men and boys were also sexually abused by slaveholders.[91] Thomas Foster says that although historians have begun to cover sexual abuse during slavery, few focus on sexual abuse of men and boys because of the assumption that only enslaved women were victimized. Foster suggests that men and boys may have also been forced into unwanted sexual activity; one problem in documenting such abuse is that they, of course, did not bear mixed-race children.[92]:448–449 Both masters and mistresses were thought to have abused male slaves.[92]:459

Angela Davis contends that the systematic rape of female slaves is analogous to the supposed medieval concept of droit du seigneur, believing that the rapes were a deliberate effort by slaveholders to extinguish resistance in women and reduce them to the status of animals.[93]

The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in a patriarchal Southern culture which treated all women, black and white, as property.[32] Although Southern mores regarded white women as dependent and submissive, black women were often consigned to a life of sexual exploitation.[32] Racial purity was the driving force behind the Southern culture's prohibition of sexual relations between white women and black men; however, the same culture protected sexual relations between white men and black women. The result was a number of mixed-race offspring.[32] Many women were raped, and had little control over their families. Children, free women, indentured servants, and men were not immune from abuse by masters and owners. Nell Irvin Painter also explains that the psychological outcome of such treatment often had the same result of "soul murder". (See Children of the plantation.) Children, especially young girls, were often subjected to sexual abuse by their masters, their masters' children, and relatives.[94] Similarly, indentured servants and slave women were often abused. Since these women had no control over where they went or what they did, their masters could manipulate them into situations of high risk, i.e. forcing them into a dark field or making them sleep in their master's bedroom to be available for service.[95] Free or white women could charge their perpetrators with rape, but slave women had no legal recourse; their bodies legally belonged to their owners.[96] This record has also given historians the opportunity to explore sexual abuse during slavery in populations other than enslaved women.

In 1662, the Southern colonies adopted into law the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, by which the children of enslaved women took the status of their mothers regardless of the ethnicity of their fathers. This was a departure from common law, which held that children took the status of their father. Some fathers freed their children, but many did not. The law relieved men of responsibility to support their children, and restricted the open secret of miscegenation to the slave quarters. However, Europeans and other visitors to the South noted the number of mixed-race slaves. During the 19th century Mary Chesnut and Fanny Kemble, whose husbands were planters, chronicled the disgrace of white men taking sexual advantage of slave women.

Resisting reproduction

Some women resisted reproduction in order to resist slavery. They found medicine or herbs to terminate pregnancies (abortifacients) or practiced abstinence. For example, chewing on cotton root was one of the more popular methods to end a pregnancy. This method was often used as the plant was readily available, especially for the women who worked in cotton fields.[97] Gossypol was one of the many substances found in all parts of the cotton plant, and it was described by scientists as 'poisonous pigment'. It appears to inhibit the development of sperm or restrict the mobility of the sperm.[97] Also, it is thought to interfere with the menstrual cycle by restricting the release of certain hormones. Women's knowledge of different forms of contraception helped them control some factors in their life.[97]

By resisting reproduction, enslaved women took control over their bodies and their lives. Richard Follet says:

by consciously avoiding pregnancy or through gynecological resistance, black women reclaimed their own bodies, frustrated the planters' pro-natalist policies, and in turn defied white male constructions of their sexuality. Whether swallowing abortifacients such as calomel and turpentine or chewing on natural contraceptives like cotton roots or okra, slave women wove contraception and miscarriages through the dark fabric of slave oppositional culture.[98]

By using various ways to resist reproduction, some women convinced their masters they could not bear children. Deborah Gray White cites several cases of women who were considered by their masters to be infertile during slavery. These women went on to have several healthy children after they were freed.[99]

Other slave women used abstinence. "Slave men and women appear to have practiced abstinence, often with the intention of denying their master any more human capital." It was not just women who resisted reproduction, in some instances men did also. An ex-slave, Virginia Yarbrough, explained how one slave woman persuaded the man that her master told her to live with to practice abstinence. After three months, the master realized that the couple were not going to produce any children, so he let her live with the man of her choice, and they had children. "By abstaining from sexual intercourse, she was able to resist her master's wishes and live and have children with the man she loved."[97]

Women resisted reproduction to avoid bringing children into slavery, and to deprive their owners of future property and profit. "In addition to the labor they provided, slaves were a profitable investment: Their prices rose steadily throughout the antebellum era, as did the return that slave owners could expect when slaves reproduced."[99] Liese M. Perrin writes, "In avoiding direct confrontation, slave women had the potential to resist in a way which pierced the very heart of slavery- by defying white slave owners the labor and profits that their children would one day provide."[97] Women knew that slave children were forced to start working at a very young age.[100] Life was harsh under slavery, with little time for a mother and child to bond. Enslaved women and their children could be separated at any time.[100] Women were forced to do heavy work even if pregnant. Sometimes this caused miscarriage or difficulties in childbirth. Richard Follett explains that "heavy physical work undermines reproductive fitness, specifically ovarian function, and thus limits success in procreation."[98] An enslaved woman carried her infant with her to field work, nursing it during brief breaks. For instance, in Freedom on My Mind', it is said that "as an infant, he rode on his mother's back while she worked in the fields to nurse."[99] Women's use of contraception was resistance and a form of strike, since slave women were expected to reproduce.[97]

Despite acts of resistance, many slave women had numerous children. Peter Kolchin notes that some historians estimate a birthrate of 7 children per slave woman during the antebellum era, which was an era of large families among free women as well.[101]

Effects on womanhood

Slave women were unable to maintain African traditions, although some were carried on. African women were born and raised to give birth;[102] there were no rituals or cultural customs in America. "Under extreme conditions the desire and ability of women to have children is reduced". Slavery removed everything that made them feel womanly, motherly, and African. A "normal" African family life was impossible; women were in the field most of the day and fathers were almost non-existent. In Africa, "Motherhood was the fulfillment of female adulthood and fertility the African women's greatest gift".[103]

Slave breeding

Slave breeding was the attempt by a slave-owner to influence the reproduction of his slaves for profit.[104] It included forced sexual relations between male and female slaves, encouraging slave pregnancies, sexual relations between master and slave to produce slave children and favoring female slaves who had many children.[105]

Nobel economist Robert Fogel disagreed in his controversial 1970s work that slave-breeding and sexual exploitation destroyed black families. Fogel argued that since the family was the basic unit of social organization under slavery, it was in the economic interest of slaveholders to encourage the stability of slave families and most did so. Most slave sales were either of entire families, or of individuals at an age when it would have been normal for them to leave home.[67] However, testimony from former slaves does not support Fogel's view. For instance, Frederick Douglass (who grew up as a slave in Maryland) reported the systematic separation of slave families and widespread rape of slave women to boost slave numbers.[106] With the development of cotton plantations in the Deep South, planters in the Upper South frequently broke up families to sell "surplus" male slaves to other markets. In addition, court cases such as those of Margaret Garner in Ohio or Celia, a slave in 19th-century Missouri, dealt with women slaves who had been sexually abused by their masters.[107]

Families

Slaves were predominantly male during the early colonial era, but the ratio of male to female slaves became more equal in later years. Under slavery, planters and other slaveholders owned, controlled, and sold entire families of slaves.[32] The slave population increased in the southern United States as native-born slaves produced large families. Slave women were at high risk for sexual abuse from slave owners and their sons, overseers, or other white men in power, as well as from male slaves.

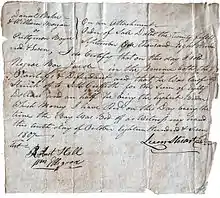

Slaves were at a continual risk of losing family members if their owners decided to sell them for profit, punishment or to pay debts. Slaveholders also made gifts of slaves to grown children (or other family members) as wedding settlements. They considered slave children to be adults, ready to work in the fields or leave home (by sale) as young as age 12 or 14. However, slave children, who of course did not go to school, were routinely given work: carrying water to the field hands, for example. A few slaves retaliated by murdering their owners and overseers, burning barns, and killing horses. But work slowdowns were the most frequent form of resistance and hard to control. Slaves also "walked away," going to the woods or a neighboring plantation for a while.[108] Slave narratives by escaped slaves published during the 19th century often included accounts of families broken up and women sexually abused.

During the early 1930s, members of the Federal Writers' Project interviewed former slaves and also made recordings of the talks (the only such records made). In 2007, the interviews were remastered, reproduced on CDs, and published in book form in conjunction with the Library of Congress, Smithsonian Productions, and a National Public Radio project. In the introduction to the oral history project (Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation), the editors wrote:

As masters applied their stamp to the domestic life of the slave quarter, slaves struggled to maintain the integrity of their families. Slaveholders had no legal obligation to respect the sanctity of the slave's marriage bed, and slave women— married or single – had no formal protection against their owners' sexual advances. ...Without legal protection and subject to the master's whim, the slave family was always at risk.[109]

The book includes a number of examples of enslaved families who were torn apart when family members were sold out of state, and accounts of sexual violation of enslaved women by men in power.

Female slave stereotypes

The evidence of white men raping slave women was obvious in the many mixed-race children who were born into slavery and part of many households. In some areas, such mixed-race families became the core of domestic and household servants, as at Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Both his father-in-law and he took mixed-race enslaved women as concubines after being widowed; each man had six children by those enslaved women. Jefferson's young concubine, Sally Hemings, was 3/4 white, the daughter of his father-in-law John Wayles, making her the half-sister of his late wife.

By the 19th century, popular Southern literature characterized female slaves as lustful and promiscuous "Jezebels" who shamelessly tempted white owners into sexual relations. This stereotype of the promiscuous slave was partially motivated by the need to rationalize the obvious sexual relations that took place between female slaves and white males, as evidenced by the children.[90] The stereotype was reinforced by female slaves' working partially clothed, due to the hot climate. During slave auctions, females were sometimes displayed nude or only partially clothed.[90] Edward Ball, in his Slaves in the Family (1995), noted that it was more often the planters' sons who took advantage of slave women before their legal marriages to white women, than did the senior planters.

Concubines and sexual slaves

Many female slaves (known as "fancy maids") were sold at auction into concubinage or prostitution, which was called the "fancy trade".[90] Concubine slaves were the only female slaves who commanded a higher price than skilled male slaves.[110]

During the early Louisiana colonial period, French men took wives and mistresses from the slaves; they often freed their children and, sometimes, their mistresses. A sizable class of free people of color developed in New Orleans, Mobile, and outlying areas. By the late 18th century white creole men of New Orleans, known as French Creoles, had a relatively formal system of plaçage among free women of color, which continued under Spanish rule. Plaçage was a public and well known system. This was evident by the fact that the largest annual ball was the "Quadroon Ball." It was an event equivalent to the white debutant ball, where young Quadroon women were paraded out for selection by their would-be Creole benefactors.[111] Mothers negotiated settlements or dowries for their daughters to be mistresses to white men. In some cases, young men took such mistresses before their marriages to white women; in others, they continued the relationship after marriage. They were known to pay for the education of their children, especially their sons, whom they sometimes sent to France for schooling and military service. These Quadroon mistresses were housed in cottages along Rampart Street the northern border of the Quarter. After the Civil War most were destitute and this area became the center of prostitution and later was chosen as the site to confine prostitution in the city and became known as Storyville.[111]

Anti-miscegenation sentiment

There was a growing feeling among whites that miscegenation was damaging to racial purity. Some segments of society began to disapprove of any sexual relationships between blacks and whites, whether slave or free, but particularly between white women and black men. In Utah, sexual relationships with a slave resulted in the slave being freed.[46]

Mixed-race children

The children of white fathers and slave mothers were mixed-race slaves, whose appearance was generally classified as mulatto. This term originally meant a person with white and black parents, but then encompassed any mixed-race person.

In New Orleans, where the Code Noir (Black Code) held sway under French and Spanish rule, people of mixed race were defined as mulatto: one half white, one half black; quadroon: three quarters white, one quarter black; octoroon: seven-eights white, one eighth black. The Code Noir prohibited marriage between those of mixed race and full-blooded, or "slave", blacks.[111] This undoubtedly formed the base of the well-known color discrimination within the black community, known as colorism.[112] In the Black community, lighter-skinned black women are preferred by black men over darker skinned black women.<Documentary Dark Girls: Bill Duke> In the Quarter, lighter-skinned blacks had a higher social position and constituted a higher percentage of the free black population.

By the turn of the 19th century many mixed-race families in Virginia dated to Colonial times; white women (generally indentured servants) had unions with slave and free African-descended men. Because of the mother's status, those children were born free and often married other free people of color.[113]

Given the generations of interaction, an increasing number of slaves in the United States during the 19th century were of mixed race. In the United States, children of mulatto and black slaves were also generally classified as mulatto. With each generation, the number of mixed-race slaves increased. The 1850, census identified 245,000 slaves as mulatto; by 1860, there were 411,000 slaves classified as mulatto out of a total slave population of 3,900,000.[88] As noted above, some mixed-race people won freedom from slavery or were born as free blacks.

If free, depending on state law, some mulattoes were legally classified as white because they had more than one-half to seven-eighths white ancestry. Questions of social status were often settled in court, but a person's acceptance by neighbors, fulfillment of citizen obligations, and other aspects of social status were more important than lineage in determining "whiteness".

Notable examples of mostly-white children born into slavery were the children of Thomas Jefferson by his mixed-race slave Sally Hemings, who was three-quarters white by ancestry. Since 2000 historians have widely accepted Jefferson's paternity, the change in scholarship has been reflected in exhibits at Monticello and in recent books about Jefferson and his era. Some historians, however, continue to disagree with this conclusion.

Speculation exists on the reasons George Washington freed his slaves in his will. One theory posits that the slaves included two half-sisters of his wife, Martha Custis. Those mixed-race slaves were born to slave women owned by Martha's father, and were regarded within the family as having been sired by him. Washington became the owner of Martha Custis' slaves under Virginia law when he married her and faced the ethical conundrum of owning his wife's sisters.[114]

Relationship of skin color to treatment

As in Thomas Jefferson's household, the use of lighter-skinned slaves as household servants was not simply a choice related to skin color. Sometimes planters used mixed-race slaves as house servants or favored artisans because they were their children or other relatives. Six of Jefferson's later household slaves were the grown children of his father-in-law John Wayles and his slave mistress Betty Hemings.[115][116] Half-siblings of Jefferson's wife Martha, she inherited them, along with Betty Hemings and other slaves, a year after her marriage to Jefferson following the death of her father. At that time some of the Hemings-Wayles children were very young; Sally Hemings was an infant. They were trained as domestic and skilled servants and headed the slave hierarchy at Monticello.[117]

Since 2000, historians have widely accepted that the widowed Jefferson had a nearly four-decade relationship with Sally Hemings, the youngest daughter of Wayles and Betty.[116] It was believed to have begun when he was US minister in Paris, and she was part of his household. Sally was nearly 25 years younger than his late wife; Jefferson had six children of record with her, four of whom survived. Jefferson had his three mixed-race sons by Hemings trained as carpenters - a skilled occupation - so they could earn a living after he freed them when they came of age. Three of his four children by Hemings, including his daughter Harriet, the only slave woman he freed, "passed" into white society as adults because of their appearance.[117][118] Some historians disagree with these conclusions about the paternity; see Jefferson-Hemings controversy.

Planters with mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their education (occasionally in northern schools) or apprenticeship in skilled trades and crafts. Others settled property on them, or otherwise passed on social capital by freeing the children and their mothers. While fewer in number than in the Upper South, free blacks in the Deep South were often mixed-race children of wealthy planters and sometimes benefited from transfers of property and social capital. Wilberforce University, founded by Methodist and African Methodist Episcopal (AME) representatives in Ohio in 1856, for the education of African-American youth, was during its early history largely supported by wealthy southern planters who paid for the education of their mixed-race children. When the American Civil War broke out, the majority of the school's 200 students were of mixed race and from such wealthy Southern families.[119] The college closed for several years before the AME Church bought and operated it.

See also

References

- Dresser, Amos (1836). "Slavery in Florida. Letters dated May 11 and June 6, 1835, from the Ohio Atlas". The narrative of Amos Dresser: with Stone's letters from Natchez, an obituary notice of the writer, and two letters from Tallahassee, relating to the treatment of slaves.

- Weld, Theodore Dwight; American Anti-Slavery Society (1839). American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society. p. iii.

- Redpath, James (1859). The roving editor: or, Talks with Slaves in the Southern States. New York: A. B. Burdick.

- Rosenwald, Mark (December 20, 2019). "Last Seen Ads". Washington Post. Retropod. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- Turner, Nat (1831). Gray, Thomas R. (ed.). Confessions. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- Allan, William T. (1834). "Facts communicated by Mr. Augustus Wattles, of Lane Seminary, to the Editor of the Western Recorder". First Annual Report of the American Anti-slavery Society; with the Speeches Delivered at the Anniversary Meeting, Held in Chatham-Street Chapel, in the City of New-York, on the 6th of May, 1834, and by Adjournment on the 8th, in the Rev. Dr. Lansing's Church; and the Minutes of the Meetings of the Society for Business. [Ron Gorman identifies the person Wattles is quoting.] New York: Dorr & Butterfield. p. 64.

- Allan, William T. (January 1837). "Testimony of Rev. William Allan". Anti-Slavery Record. Vol. 3 no. 1. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- Browne, Stephen H. (1999). Angelina Grimké: rhetoric, identity, and the radical imagination. Michigan State University Press. p. 156. ISBN 0870135309. Archived from the original on 2019-10-24. Retrieved 2019-10-21 – via Project MUSE.

- Bradley, James (June 1834), Brief Account of an Emancipated Slave Written by Himself, archived from the original on June 29, 2016, retrieved October 31, 2019

- Doolitle, J[ames] R. (June 15, 1860). "Views of the minority". Report [of] the Select committee of the Senate appointed to inquire into the late invasion and seizure of the public property at Harper's Ferry. United States Senate. p. 25.

- Cartwright, Samuel A. "Report on the Diseases of and Physical Peculiarities of the Negro Race". In Finkelman, Paul (ed.). Defending Slavery. Proslavery thought in the Old South. A Brief History with Documents. pp. 157–173, at pp. 160–161.

- "Communicated". Savannah Republican (Savannah, Georgia). August 28, 1835. p. 3. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019 – via newspaperarchive.com.

- "The Anti-Slavery Agitators". Richmond Enquirer. Reprinted from the New Hampshire Patriot. June 24, 1834. p. 4. Archived from the original on 2020-09-11. Retrieved 2020-02-07.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "The Excitement — The Fanatics". The Liberator. Reprinted from the Washington Telegraph. August 29, 1835. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 26, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via newspapers.com.CS1 maint: others (link)