Tuskahoma, Oklahoma

Tuskahoma is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in northern Pushmataha County, Oklahoma, United States, four miles east of Clayton. It was the former seat of the Choctaw Nation government prior to Oklahoma statehood. The population at the 2010 census was 151.[1]

Tuskahoma | |

|---|---|

Choctaw Capitol Building in Tuskahoma, Oklahoma, September 22, 2009 | |

| Motto(s): The Red Warrior | |

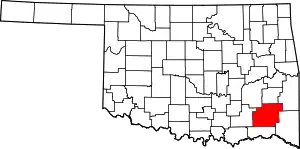

Tuskahoma Location in the state of Oklahoma  Tuskahoma Tuskahoma (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 34°37′4″N 95°16′36″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oklahoma |

| County | Pushmataha |

| Elevation | 600 ft (200 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 151 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 74574 |

History

A United States Post Office was established at Tushka Homma, Indian Territory on February 27, 1885. On October 28, 1891, the spelling changed to Tushkahomma. On December 6, 1910 the official spelling changed to its present rendering, Tuskahoma. The community has also been served by post office locations at nearby Council House (1872–1880) and Lyceum (1896–1900). Council House was located at the Choctaw Capitol Building and Lyceum was located at the former Choctaw Female Academy.[2]

Tuskahoma is a compound word meaning “red warrior” in the Choctaw language.[3] The spelling was originally rendered as "Tvshka Homma" in an 1852 Choctaw-English dictionary published by a missionary, the Rev. Cyrus Byington. The apparent lower-case "v" is actually a Greek letter, upsilon, which represents what Byington described as a "u short" sound.[4] In recent years, the Choctaw Nation's official publications have switched to this spelling.[5]

Tuskahoma was designated as (political) capital of the Choctaw Nation in 1882 when an Act of the Choctaw Nation dated October 20, 1882, established the community as the permanent seat of government. The Nation's first capital after the Trail of Tears was at Nanih [Nunih] Waiyah, two miles east of Tuskahoma. [It was named after "Nunih Waiyah," a sacred mound in Mississippi where the Choctaw brought the bones of their ancestors to rest and established the tribe. The mound was built by an earlier people, but it became sacred to the Choctaw as well.] Afterward, during a time of constitutional experimentation, the Choctaw shifted their capital from Nanih Waiyah to Doaksville, Skullyville, Fort Towson and Boggy Depot. The Choctaw wartime capital during the Civil War was located at Armstrong Academy, also known as Chahta Tamaha.[6]

After the Choctaw Nation decided to make Tuskahoma the permanent capital, it decided to construct an appropriate building to house the government. A spacious Choctaw Capitol Building was completed in the fall of 1884. It was two stories, brick, with a garret under its French mansard roof. Many called it the finest building in the Indian Territory. It included large rooms for the Senate, House of Representatives, and Supreme Court. Also included were an Executive Office for the Principal Chief, or Governor, of the Choctaw Nation, five smaller rooms for the national officers, and five committee rooms. It was heated by numerous fireplaces.[3]

Almost immediately, a bustling town sprang up by the Capitol building. Several hotels, boarding houses, barber shops, stores, blacksmith shop, photographer's tent, and homes were built. But when the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway built its tracks through the Kiamichi River valley in the mid-1880s, they ran two miles to the south of the Capitol. Business flocked to the vicinity of the new Tuskahoma railroad station and the Capitol precinct was abandoned, except during sessions of the government.[7]

This twist of history altered Tuskahoma's prominence. The Choctaw Nation constitution directed the constitutional officers, such as Principal Chief, National Secretary, National Treasurer, National Auditor and National Attorney to reside “at or near the seat of government”, but this provision was never enforced. During the National Council's first session in its new Capitol, the principal chief of the day, J.F. McCurtain, proposed building five homes on the site to accommodate the national officers, but this was never done.[7]

In addition to serving as a government center, Tuskahoma was also intended to be a cultural center and was the location of the Choctaw Nation's national girls' school. Tuskahoma Female Academy [or Institute] opened in 1892 at nearby Lyceum, with Peter J. Hudson serving as superintendent. The academy, also known as the Choctaw Female Academy, occupied a classical-style two-story colonnaded building. It burned in 1925 and was not rebuilt. [Noted Choctaw educator Anna Lewis, who had attended the school, bought the site and used materials from the ruins to build her family home, which she called Nunih Waiyah.[8]] From that time forward, Tuskahoma's role as a center of education ceased.[9]

Tuskahoma's new site along the railroad prospered, and became a vibrant community and trading center. Banks, hotels, stores, churches, a school, and numerous homes lined its commercial district and residential streets. Its importance began to wane during the middle and later years of the 20th century, as commerce shifted to nearby Clayton or elsewhere, following the construction of highways and shifting of transport off the railroads.[10]

Prior to Oklahoma's statehood, Tuskahoma and the Choctaw Capitol Building were located in Wade County, Choctaw Nation.[11] More information on Tuskahoma may be found in the Pushmataha County Historical Society.

Geography

Local transportation was revolutionized during the 1950s by the construction of U.S. Highway 271, which provided paved all-weather highway connections to Clayton and the county seat at Antlers to the east and south, and Talihina, Wilburton and Poteau to the northeast.

The Kiamichi River, important as a source of water, is not navigable at Tuskahoma and has never played a role in local transportation. It did, however, cause the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway to place its station at Tuskahoma's present location, due to the trains’ need for a reliable water supply, rather than its original location at the Capitol.

The Kiamichi Mountains define life in the Tuskahoma region, which is one of Oklahoma's most scenic areas. The Kiamichi River valley stretches to the east and west of the community. To the north lie the unusually serrated Potato Hills, with peaks topping out at approximately 1,000 feet in elevation. To the south is a scenic but imposing mountain wilderness, with summits topping off at approximately 1,600 feet in elevation. Here, roads do not penetrate and all transportation is via unimproved—but marked and fairly well maintained—timber company roads, including Clayton Trail, Hurd Creek Trail, K Trail, Cripple Mountain Trail and Black Fork Trail.

Unusual and striking geological features abound in the Tuskahoma region. Its valley—one of the prettiest in Oklahoma—is of special note. The Potato Hills, a group of tall outcroppings eroded from prehistoric mountains, are a regional landmark. To the north of Tuskahoma lies McKinley Rocks, a series of massive white boulders seemingly strewn across the top of a mountain. Access is difficult, causing a WPA survey crew to recommend during the 1930s that the site, while abounding in scenic beauty, should not become a state park due to lack of roads. The rocks, which afford views for miles in any direction, were first noted by a Choctaw survey party during the late 1890s. They are named in honor of the 26th President of the United States, William McKinley.[12]

Choctaw Nation Labor Day Festival

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma holds its annual Labor Day Festival (pow-wow) in Tuskahoma on the grounds of the Capitol building. Attendance ranges from 50,000 - 100,000 over the course of the festival, people coming from all corners of the United States. The festival features various events from country and gospel music concerts to softball games, and pow-wows, arts and crafts, basketball games, strength contests, a carnival, animal shows, horseshoe games, bison tours, volleyball games, a swimming pool, tent and RV grounds, a 5K run, playgrounds, a museum, and numerous other events.

During recent years the Choctaw Capitol Building has been recognized as an architecturally and historically significant structure, and has been added to the National Register of Historic Places. It hosts the Choctaw Nation Labor Day Festival and provides the centerpiece for the festivities.

Climate

| Climate data for Tuskahoma, Oklahoma. (Elevation 600ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

97 (36) |

107 (42) |

112 (44) |

114 (46) |

112 (44) |

101 (38) |

87 (31) |

80 (27) |

114 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53.1 (11.7) |

58.2 (14.6) |

67.2 (19.6) |

75.2 (24.0) |

81.3 (27.4) |

88.7 (31.5) |

94.6 (34.8) |

95.0 (35.0) |

87.3 (30.7) |

77.0 (25.0) |

64.4 (18.0) |

55.0 (12.8) |

74.8 (23.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 29.1 (−1.6) |

33.1 (0.6) |

41.7 (5.4) |

49.7 (9.8) |

58.5 (14.7) |

66.5 (19.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

69.1 (20.6) |

61.9 (16.6) |

50.5 (10.3) |

40.7 (4.8) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

50.2 (10.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −13 (−25) |

−4 (−20) |

5 (−15) |

21 (−6) |

32 (0) |

40 (4) |

47 (8) |

47 (8) |

32 (0) |

18 (−8) |

7 (−14) |

−10 (−23) |

−13 (−25) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.94 (75) |

2.97 (75) |

3.68 (93) |

5.10 (130) |

5.95 (151) |

4.89 (124) |

3.38 (86) |

2.92 (74) |

4.40 (112) |

4.45 (113) |

4.02 (102) |

3.32 (84) |

48.02 (1,220) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.7 (4.3) |

1.3 (3.3) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.4 (1.0) |

4.0 (10) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[13] | |||||||||||||

References

- CensusViewer:Tuskahoma, Oklahoma Population

- George H. Shirk, Oklahoma Place Names, pp. 55, 130, 209-210; Post Office Site Location Reports, Record Group 28, National Archives.

- Angie Debo, Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, pp. 158-159.

- Cyrus Byington, An English and Choctaw Definer: for the Choctaw Academies and Schools (New York: S.W. Benedict, 1852), p. 3.

- The federal government adopted the spelling, "Tuskahoma," as early as 1910. Its official arbiter of place names, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, continues using this spelling.

- Debo, pp. 75-76, 158-159.

- Debo, p. 159.

- Linda Reese, "Dr. Anna Lewis: Historian at Oklahoma College for Women," Chronicles of Oklahoma 82.4 (2004) pp. 428-449

- Debo, p. 239.

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps on microfilm, Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries.

- Morris, John W. Historical Atlas of Oklahoma (Norman: University of Oklahoma, 1986), plate 38.

- WPA Papers, Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries.

- "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 4, 2013.