USS Saginaw Bay

USS Saginaw Bay (CVE-82) was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. It was named after Saginaw Bay, located within Kuiu Island. The bay was in turn named after USS Saginaw, a U.S. Navy sloop-of-war that spent 1868 and 1869 charting and exploring the Alaskan coast. Launched in January 1944, and commissioned in March, she served in support of the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, the Philippines campaign, the Invasion of Iwo Jima, and the Battle of Okinawa. Postwar, she participated in Operation Magic Carpet. She was decommissioned in April 1946, when she was mothballed in the Atlantic Reserve Fleet. Ultimately, she was sold for scrapping in November 1959.

_underway_at_sea%252C_circa_1944.jpg.webp) USS Saginaw Bay underway, circa 1944 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Saginaw Bay |

| Namesake: | Saginaw Bay, Kuiu Island, Alaska |

| Ordered: | as a Type S4-S2-BB3 hull, MCE hull 1119[1] |

| Awarded: | 18 June 1942 |

| Builder: | Kaiser Shipyards |

| Laid down: | 1 November 1943 |

| Launched: | 19 January 1944 |

| Commissioned: | 2 March 1944 |

| Decommissioned: | 19 June 1946 |

| Stricken: | 1 March 1959 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol: CVE-82 |

| Honors and awards: | 5 Battle stars |

| Fate: | Sold for scrapping 27 November 1959 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Casablanca-class escort carrier |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | |

| Beam: |

|

| Draft: | 20 ft 9 in (6.32 m) (max) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Range: | 10,240 nmi (18,960 km; 11,780 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: | 27 |

| Aviation facilities: | |

| Service record | |

| Part of: |

|

| Operations: |

|

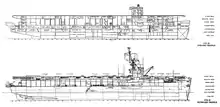

Design and description

Saginaw Bay was a Casablanca-class escort carrier, the most numerous type of aircraft carriers ever built,[2] and designed specifically to be mass-produced using prefabricated sections, in order to replace heavy early war losses. Standardized with her sister ships, she was 512 ft 3 in (156.13 m) long overall, had a beam of 65 ft 2 in (19.86 m), and a draft of 20 ft 9 in (6.32 m). She displaced 8,188 long tons (8,319 t) standard, 10,902 long tons (11,077 t) with a full load. She had a 257 ft (78 m) long hangar deck and a 477 ft (145 m) long flight deck. She was powered with two Uniflow reciprocating steam engines, which drove two shafts, providing 9,000 horsepower (6,700 kW), thus enabling her to make 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 10,240 nautical miles (18,960 km; 11,780 mi) at a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). Her compact size necessitated the installment of an aircraft catapult at her bow, and there were two aircraft elevators to facilitate movement of aircraft between the flight and hangar deck: one each fore and aft.[3][2][4]

One 5-inch (127 mm)/38 caliber dual-purpose gun was mounted on the stern. Anti-aircraft defense was provided by eight 40-millimeter (1.6 in) Bofors anti-aircraft guns in single mounts, as well as twelve 20-millimeter (0.79 in) Oerlikon cannons, which were mounted around the perimeter of the deck. By the end of the war, Casablanca-class carriers had been modified to carry thirty 20–mm cannons, and the amount of 40–mm guns had been doubled to sixteen, by putting them into twin mounts. These modifications were in response to increasing casualties due to kamikaze attacks. Casablanca-class escort carriers were designed to carry 27 aircraft, but Saginaw Bay sometimes went over or under this number. For example, during the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, she carried 18 FM-2 fighters, and 12 TBM-1C torpedo bombers, for a total of 30 aircraft.[5] However, during the Philippines campaign, she carried 20 FM-2 fighters and 12 TBM-3 torpedo bombers, for a total of 32 aircraft.[6] During the Invasion of Iwo Jima, she carried 20 FM-2 fighters and 12 TBM-3 torpedo bombers, for a total of 32 aircraft.[7] During the Battle of Okinawa, she carried 19 FM-2 fighters, 11 TBM-3 torpedo bombers, and a TBM-3P reconnaissance aircraft, for a total of 31 aircraft.[8][4]

Construction

A contract for fifty Casablanca-class escort carriers was made on 18 June 1942, with the construction being awarded to the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company, Vancouver, Washington. All fifty were commissioned in the span of a single year. Saginaw Bay was laid down on 1 November 1943 under a Maritime Commission contract, MC hull 1119, by Kaiser Shipbuilding Company, Vancouver, Washington. She was launched on 19 January 1944, and was sponsored by Mrs. Howard L. Vickery. After construction was completed, the ship was transferred to the United States Navy and commissioned on 2 March. Upon commissioning, Saginaw Bay was under the command of Captain Frank Carlin Sutton Jr.[1][9]

Service history

World War II

_on_14_June_1944_(80-G-334948).jpg.webp)

Upon being commissioned, she underwent a shakedown cruise off of San Diego. On 15 April 1944, Saginaw Bay loaded aircraft and their pilots from Terminal Island for transport to Hawaii. She arrived at Pearl Harbor on 21 April, where she unloaded her cargo in exchange for damaged planes, before returning to Alameda, California. She proceeded to conduct pilot qualifications off the coast of San Diego throughout May and early June, during which a FM-2 fighter crashed into the sea, killing its pilot. After completing her exercises, she underwent a second replenishment aircraft ferry mission, arriving at Pearl Harbor on 5 July.[9][10]

After taking on a load of aircraft, she proceeded westward to Enewetak Atoll and Majuro before returning to San Diego. On 13 August, she left, bound for the Solomon Islands, where she would act as the flagship for Carrier Division 28, commanded by Rear Admiral George R. Henderson.[11] There, she prepared for the invasion of the Palaus. From 15 September to 9 October, her task group provided air cover over Peleliu and Anguar.[9][12]

She retired to Seeadler Harbor, located within Manus Island, where plans were drawn for the landings on Leyte. She joined "Taffy 1", along with 12 other escort carriers, under the command of Rear Admiral Thomas L. Sprague. "Taffy 1" was assigned the task of guarding the southeast entrance into Leyte Gulf.[13] On 14 October, the task group departed, guarding troop transports along the way, arriving within Leyte Gulf by 20 October. As the Japanese Fleet closed in for a decisive engagement on 24 October, Saginaw Bay and Chenango transferred much of their aircraft contingent to other carriers.[14] She then retired to Morotai for replacement aircraft, missing the ensuing Battle off Samar. She rejoined her task unit on 28 October with a new aircraft contingent, just as it started to retire back to Manus.[9][15]

Saginaw Bay was anchored in Seeadler Harbor on 10 November when the ammunition ship Mount Hood underwent a catastrophic explosion. She suffered only minor damage from the blast and resulting tidal wave. During her layover, she was taken into dry dock for repairs. From 14 December to the 21st, she underwent exercises in preparation for amphibious landings at Lingayen. On 2 January 1945, her task group departed Manus, escorting transports, arriving at Lingayen Gulf just in time to support the landings on 9 January.[16] On 10 January, she came under attack from two Japanese bombers, who dropped bombs, which missed. On 14 January, a torpedo was spotted near her hull, which also missed. During this period of activity, Kitkun Bay was heavily damaged by a kamikaze, and Ommaney Bay was sunk by one, complicating the task group's efforts to provide air support. Efforts were also hampered by heavy seas, which made landings on her flight deck precarious. On 21 January, she retired from supporting the landings, steaming back to Ulithi, in preparation for the landings upon Iwo Jima.[9][17]

On 23 January, she participated in a rehearsal of the Iwo Jima landings in Ulithi. On 10 February, her task group departed Ulithi en route to Iwo Jima, making a stop at Saipan along the way. On 19 February, she supported the landings and provided air support until 11 March. During operations, the carrier task group was constantly harried by kamikazes. Her crew witnessed the escort carrier Bismarck Sea get hit by two kamikazes, before sinking from the resulting blaze.[18] On 11 March, she departed from Iwo Jima bound for Ulithi, with Japanese forces still entrenched within the northern half of the island.[9][19]

On 14 March, she arrived back at Ulithi, where Captain Robert Goldthwaite assumed command. Saginaw Bay was quickly returned into action, departing for Okinawa on 21 March, arriving on 24 March. There, she immediately began operations in preparation for the landings, which proceeded until 29 April. On 2 April, her anti-aircraft guns shot down a Japanese plane which dove towards her, while she was loading ammunition within Kerama Retto Harbor.[20] Throughout the battle, her aircraft claimed eleven Japanese planes. On 29 April, she was ordered back to the United States, making stops at Guam, Pearl Harbor, arriving at San Francisco on 22 May, where she underwent repairs. After repairs were finished, she then proceeded down to San Diego, where she delivered planes to Guam, returning on 20 August. En route, the surrender of Japan was announced.[9][21]

Post war

Following the end of the war, she steamed for Hawaii, where she underwent training operations before being incorporated into Operation Magic Carpet, which repatriated U.S. servicemen from throughout the Pacific. On 14 September, she departed Hawaii, making stops at Guiuan Roadstead, Samar, and San Pedro Bay, Leyte, where she took on servicemen. She then returned to San Francisco. She then made a second Magic Carpet run to Buckner Bay, Okinawa, before proceeding back for San Francisco.[9][22]

On 1 February 1946, she was discharged from the Magic Carpet fleet, and departed San Francisco for Boston Naval Shipyard, on the Eastern seaboard. She arrived on 23 February for inactivation, and she was subsequently decommissioned on 19 June. She was assigned to the Boston Group of the U.S. Atlantic Reserve Fleet. On 12 June 1955, she was reclassified as CVHE-82, but she was never converted. On 1 March 1959, she was struck from the navy list and sold to Louis Simmons on 27 November. In April 1960, she was broken up in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.[9][23]

References

- Kaiser Vancouver 2010.

- Chesneau & Gardiner 1980, p. 109.

- Y'Blood 2014, pp. 34–35.

- Hazegray 1998.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 109.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 277.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 322.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 349.

- DANFS 2016.

- McCarty, p. 1.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 120.

- McCarty, p. 2.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 128.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 142.

- McCarty, p. 3.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 309.

- McCarty, pp. 4–6.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 331.

- McCarty, p. 7.

- Y'Blood 2014, p. 356.

- McCarty, pp. 8–9.

- McCarty, p. 10.

- McCarty, p. 11.

Sources

Online sources

- "Saginaw Bay (CVE-82)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "Kaiser Vancouver, Vancouver WA". www.ShipbuildingHistory.com. 27 November 2010. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "World Aircraft Carriers List: US Escort Carriers, S4 Hulls". Hazegray.org. 14 December 1998. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- McCarty, Dennis B. "USS Saginaw Bay CVE 82 – Ships Movement History" (PDF). navsource.org. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

Bibliography

- Chesneau, Robert; Gardiner, Robert (1980), Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946, London, England: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 9780870219139

- Y'Blood, William T. (2014), The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers Against Japan (E-book), Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 9781612512471

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Saginaw Bay (CVE-82). |

- Photo gallery of USS Saginaw Bay (CVE-82) at NavSource Naval History