United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS),[3] or State Department,[4] is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the nation's foreign policy and international relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nations, its primary duties are advising the U.S. president, administering diplomatic missions, negotiating international treaties and agreements, and representing the U.S. at the United Nations.[5] The department is headquartered in the Harry S Truman Building, a few blocks away from the White House, in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C.; "Foggy Bottom" is thus sometimes used as a metonym.

Seal of the Department of State | |

Flag of the Department of State | |

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | July 27, 1789 |

| Preceding agency |

|

| Type | Executive department |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Harry S Truman Building 2201 C Street Northwest, Washington, D.C., U.S. 38°53′39″N 77°2′54″W |

| Employees | 13,000 Foreign Service employees 11,000 Civil Service employees 45,000 local employees[1] |

| Annual budget | $52.505 billion (FY 2020)[2] |

| Agency executives | |

| Website | State.gov |

Established in 1789 as the first administrative arm of the U.S. executive branch, the State Department is considered one of the most powerful and prestigious executive agencies.[6] It is led by the secretary of state, a member of the Cabinet who is nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Analogous to a foreign minister, the secretary of state serves as the federal government's chief diplomat and representative abroad, and is the first Cabinet official in the order of precedence and in the presidential line of succession. The position is currently held by Antony Blinken who was appointed by President Joe Biden and confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 26th, 2021 by a vote of 78-22. [7]

As of 2019, the State Department maintains 273 diplomatic posts worldwide, second only to China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.[8] It also manages the U.S. Foreign Service, provides diplomatic training to U.S. officials and military personnel, exercises partial jurisdiction over immigration, and provides various services to Americans, such as issuing passports and visas, posting foreign travel advisories, and advancing commercial ties abroad. The department administers the oldest U.S. civilian intelligence agency, the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, and maintains a law enforcement arm, the Diplomatic Security Service.

History

Origin and early history

The U.S. Constitution, drafted September 1787 and ratified the following year, gave the President responsibility for conducting the federal government's affairs with foreign states.

To that end, on July 21, 1789, the First Congress approved legislation to establish a Department of Foreign Affairs, which President George Washington signed into law on July 27, making the Department the first federal agency to be created under the new Constitution.[9] This legislation remains the basic law of the Department of State.[10]

In September 1789, additional legislation changed the name of the agency to the Department of State and assigned it a variety of domestic duties, including managing the United States Mint, keeping the Great Seal of the United States, and administering the census. President Washington signed the new legislation on September 15.[11] Most of these domestic duties were gradually transferred to various federal departments and agencies established during the 19th century. However, the Secretary of State still retains a few domestic responsibilities, such as serving as keeper of the Great Seal and being the officer to whom a President or Vice President wishing to resign must deliver an instrument in writing declaring the decision.

On September 29, 1789, Washington appointed Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, then Minister to France, as the first U.S. Secretary of State.[12] John Jay had been serving as Secretary of Foreign Affairs as a holdover from the Confederation since before Washington took office; he would continue in that capacity until Jefferson returned from Europe many months later. Reflecting the fledgling status of the U.S. at the time, Jefferson's department comprised only six personnel, two diplomatic posts (in London and Paris), and 10 consular posts.[13]

Eighteenth to nineteenth centuries

For much of its history, the State Department was composed of two primary administrative units: the diplomatic service, which staffed U.S. legations and embassies, and the consular service, which was primarily responsible for promoting American commerce abroad and assisting distressed American sailors.[14] Each service developed separately, but both lacked sufficient funding to provide for a career; consequently, appointments to either service fell on those with the financial means to sustain their work abroad. Combined with the common practice of appointing individuals based on politics or patronage, rather than merit, this led the Department to largely favor those with political networks and wealth, rather than skill and knowledge.[15]

Twentieth century reforms and growth

The Department of State underwent its first major overhaul with the Rogers Act of 1924, which merged the diplomatic and consular services into the Foreign Service, a professionalized personnel system under which the Secretary of State is authorized to assign diplomats abroad. An extremely difficult Foreign Service examination was also implemented to ensure highly qualified recruits, along with a merit-based system of promotions. The Rogers Act also created the Board of the Foreign Service, which advises the Secretary of State on managing the Foreign Service, and the Board of Examiners of the Foreign Service, which administers the examination process.

The post-Second World War period saw an unprecedented increase in funding and staff commensurate with the U.S.' emergence as a superpower and its competition with the Soviet Union in the subsequent Cold War.[16] Consequently, the number of domestic and overseas employees grew from roughly 2,000 in 1940 to over 13,000 in 1960.[16]

In 1997, Madeleine Albright became the first woman appointed Secretary of State and the first foreign-born woman to serve in the Cabinet.

Twenty-first century

The 21st century saw the Department reinvent itself in response to the rapid digitization of society and the global economy. In 2007, it launched an official blog, Dipnote, as well as a Twitter account of the same name, to engage with a global audience. Internally, it launched a wiki, Diplopedia; a suggestion forum called the Sounding Board;[17] and a professional networking software, "Corridor".[18][19] In May 2009, the Virtual Student Federal Service (VSFS) was created to provide remote internships to students.[20] The same year, the Department of State was the fourth most desired employer for undergraduates according to BusinessWeek.[21]

From 2009 to 2017, the State Department launched 21st Century Statecraft, with the official goal of "complementing traditional foreign policy tools with newly innovated and adapted instruments of statecraft that fully leverage the technologies of our interconnected world."[22] The initiative was designed to utilize digital technology and the Internet to promote foreign policy goals; examples include promoting an SMS campaign to provide disaster relief to Pakistan,[23] and sending DOS personnel to Libya to assist in developining Internet infrastructure and e-government.[24]

Colin Powell, who led the department from 2001 to 2005, became the first African-American to hold the post; his immediate successor, Condoleezza Rice, was the second female Secretary of State and the second African-American. Hillary Clinton became the third female Secretary of State when she was appointed in 2009.

In 2014, the State Department began expanding into the Navy Hill Complex across 23rd Street NW from the Truman Building.[25] A joint venture consisting of the architectural firms of Goody, Clancy and the Louis Berger Group won a $2.5 million contract in January 2014 to begin planning the renovation of the buildings on the 11.8 acres (4.8 ha) Navy Hill campus, which housed the World War II headquarters of the Office of Strategic Services and was the first headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency.[26]

Duties and responsibilities

The Executive Branch and the Congress have constitutional responsibilities for U.S. foreign policy. Within the Executive Branch, the Department of State is the lead U.S. foreign affairs agency, and its head, the Secretary of State, is the President's principal foreign policy advisor. The Department advances U.S. objectives and interests in the world through its primary role in developing and implementing the President's foreign policy. It also provides an array of important services to U.S. citizens and to foreigners seeking to visit or immigrate to the United States.

All foreign affairs activities—U.S. representation abroad, foreign assistance programs, countering international crime, foreign military training programs, the services the Department provides, and more—are paid for by the foreign affairs budget, which represents little more than 1% of the total federal budget.[27]

The Department's core activities and purpose include:

- Protecting and assisting U.S. citizens living or traveling abroad;

- Assisting American businesses in the international marketplace;

- Coordinating and providing support for international activities of other U.S. agencies (local, state, or federal government), official visits overseas and at home, and other diplomatic efforts.

- Keeping the public informed about U.S. foreign policy and relations with other countries and providing feedback from the public to administration officials.

- Providing automobile registration for non-diplomatic staff vehicles and the vehicles of diplomats of foreign countries having diplomatic immunity in the United States.[28]

The Department of State conducts these activities with a civilian workforce, and normally uses the Foreign Service personnel system for positions that require service abroad. Employees may be assigned to diplomatic missions abroad to represent the United States, analyze and report on political, economic, and social trends; adjudicate visas; and respond to the needs of U.S. citizens abroad.

The U.S. maintains diplomatic relations with about 180 countries and maintains relations with many international organizations, adding up to a total of more than 250 posts around the world. In the United States, about 5,000 professional, technical, and administrative employees work compiling and analyzing reports from overseas, providing logistical support to posts, communicating with the American public, formulating and overseeing the budget, issuing passports and travel warnings, and more. In carrying out these responsibilities, the Department of State works in close coordination with other federal agencies, including the department of Defense, Treasury, and Commerce. The Department also consults with Congress about foreign policy initiatives and policies.[29]

Organization

Secretary of State

.jpg.webp)

The Secretary of State is the chief executive officer of the Department of State and a member of the Cabinet that answers directly to, and advises, the President of the United States. The secretary organizes and supervises the entire department and its staff.[30]

Staff

Under the Obama administration, the website of the Department of State had indicated that the State Department's 75,547 employees included 13,855 Foreign Service Officers; 49,734 Locally Employed Staff, whose duties are primarily serving overseas; and 10,171 predominantly domestic Civil Service employees.[31]

- United States Deputy Secretary of State: The Deputy Secretary (with the Chief of Staff, Executive Secretariat, and the Under Secretary for Management) assists the Secretary in the overall management of the department. Reporting to the Deputy Secretary are the six Under Secretaries and the counselor, along with several staff offices:

- Chief of Staff

- Counselor: Ranking with the Under Secretaries, the Counselor is the Secretary's and Deputy Secretary's special advisor and consultant on major problems of foreign policy. The Counselor provides guidance to the appropriate bureaus with respect to such matters, conducts special international negotiations and consultations, and undertakes special assignments from time to time as directed by the Secretary.

- Bureau of Intelligence and Research

- Bureau of Legislative Affairs

- Executive Secretariat

- Office of Civil Rights

- Office of Foreign Assistance

- Office of Global Women's Issues

- Office of the Chief of Protocol

- Office of the Coordinator for Cyber Issues

- Office of the Legal Adviser

- Office of the Ombudsman

- Office of the Secretary’s Special Representative for Syria Engagement

- Office of the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs

- Policy Planning Staff

- Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation

- Special Representative for Iran

- Special Representative for Venezuela

- The Global Coalition To Defeat ISIS

- United States Security Coordinator for Israel and the Palestinian Authority

- Office of Global AIDS Coordinator & Health Diplomacy: The President's main task force to combat global AIDS. The Global AIDS Coordinator reports directly to the Secretary of State.

- Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs: The fourth-ranking State Department official. Becomes Acting Secretary in the absence of the Secretary of State and the two Deputy Secretaries of State. This position is responsible for bureaus, headed by Assistant Secretaries, coordinating American diplomacy around the world:

- Under Secretary of State for Management:[32] The principal adviser to the Secretary and Deputy Secretary on matters relating to the allocation and use of Department's budget, physical property, and personnel. This position is responsible for bureaus, headed by Assistant Secretaries, planning the day-to-day administration of the Department and proposing institutional reform and modernization:

- Bureau of Administration

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is greeted by Department employees during her arrival on her first day.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton is greeted by Department employees during her arrival on her first day. - Bureau of Budget and Planning

- Bureau of Consular Affairs

- Bureau of Diplomatic Security (DS)

- Office of Foreign Missions

- Bureau of Global Talent Management & the United States Foreign Service

- Bureau of Information Resource Management

- Bureau of Medical Services[33][34]

- Bureau of Overseas Buildings Operations

- Director of Diplomatic Reception Rooms

- Foreign Service Institute

- Office of Management Strategy and Solutions

- Under Secretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment: The senior economic advisor for the Secretary and Deputy Secretary on international economic policy. This position is responsible for bureaus, headed by Assistant Secretaries, dealing with trade, agriculture, aviation, and bilateral trade relations with America's economic partners:

- Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs

- Bureau of Energy Resources

- Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs

- Office of Global Partnerships

- Office of the Science and Technology Adviser[35]

- Office of the Chief Economist

- Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs: This Under Secretary leads functions that were formerly assigned to the United States Information Agency but were integrated into the State Department by the 1999 reorganization. This position manages units that handle the department's public communications and seek to burnish the image of the United States around the world:

- Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

- Bureau of Public Affairs

- Bureau of International Information Programs

- Office of Policy, Planning, and Resources for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs

- Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs: This Under Secretary coordinates the Department's role in U.S. military assistance. Since the 1996 reorganization, this Under Secretary also oversees the functions of the formerly independent Arms Control and Disarmament Agency.

- Under Secretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights: This Under Secretary leads the Department's efforts to prevent and counter threats to civilian security and advises the Secretary of State on matters related to governance, democracy, and human rights.

- Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations

- Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization

- Bureau of Counterterrorism

- Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

- Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs

- Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration

- Office of Global Criminal Justice

- Office of Global Youth Issues

- Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons

- Global Engagement Center[36]

- Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations

Other agencies

Since the 1996 reorganization, the Administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), while leading an independent agency, also reports to the Secretary of State, as does the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations.

Vacancies

As of November 2018, people nominated to ambassadorships to 41 countries had not yet been confirmed by the Senate, and no one had yet been nominated to ambassadorships to 18 additional countries (including Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Mexico, Pakistan, Egypt, Jordan, South Africa, and Singapore).[37] In November 2019, a quarter of U.S. embassies around the world—including Japan, Russia and Canada—still had no ambassador.[38]

Headquarters

.jpg.webp)

From 1790 to 1800, the State Department was headquartered in Philadelphia, the national capital at the time.[39] It occupied a building at Church and Fifth Street.[40][Note 1] In 1800, it moved from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., where it briefly occupied the Treasury Building[40] and then the Seven Buildings at 19th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue.[41]

The State Department moved several times throughout the capital in the ensuing decades, including Six Buildings in September 1800;[42] the War Office Building west of the White House the following May;[43] the Treasury Building once more from September 1819 to November 1866;[44][Note 2][43] the Washington City Orphan Home from November 1866 to July 1875;[45] and the State, War, and Navy Building in 1875.[46]

Since May 1947, the State Department has been based in the Harry S. Truman Building, which was originally intended to house the Department of Defense; it has since undergone several expansions and renovations, most recently in 2016.[47] Previously known as the "Main State Building", in September 2000 it was renamed in honor of President Harry S. Truman, who was a major proponent of internationalism and diplomacy.[48]

As the DOS is located in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, it is sometimes metonymically referred to as "Foggy Bottom".[49][50][51]

Programs

Fulbright Program

.jpg.webp)

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is a program of competitive, merit-based grants for international educational exchange for students, scholars, teachers, professionals, scientists and artists, founded by United States Senator J. William Fulbright in 1946. Under the Fulbright Program, competitively selected U.S. citizens may become eligible for scholarships to study, conduct research, or exercise their talents abroad; and citizens of other countries may qualify to do the same in the United States. The program was established to increase mutual understanding between the people of the United States and other countries through the exchange of persons, knowledge, and skills.

The Fulbright Program provides 8,000 grants annually to undertake graduate study, advanced research, university lecturing, and classroom teaching. In the 2015–16 cycle, 17% and 24% of American applicants were successful in securing research and English Teaching Assistance grants, respectively. However, selectivity and application numbers vary substantially by country and by type of grant. For example, grants were awarded to 30% of Americans applying to teach English in Laos and 50% of applicants to do research in Laos. In contrast, 6% of applicants applying to teach English in Belgium were successful compared to 16% of applicants to do research in Belgium.[52][53]

The U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs sponsors the Fulbright Program from an annual appropriation from the U.S. Congress. Additional direct and in-kind support comes from partner governments, foundations, corporations, and host institutions both in and outside the U.S.[54] The Fulbright Program is administered by cooperating organizations like the Institute of International Education. It operates in over 160 countries around the world.[55] In each of 49 countries, a bi-national Fulbright Commission administers and oversees the Fulbright Program. In countries without a Fulbright Commission but that have an active program, the Public Affairs Section of the U.S. Embassy oversees the Fulbright Program. More than 360,000 persons have participated in the program since it began. Fifty-four Fulbright alumni have won Nobel Prizes;[56] eighty-two have won Pulitzer Prizes.[57]

Jefferson Science Fellows Program

The Jefferson Science Fellows Program was established in 2003 by the DoS to establish a new model for engaging the American academic science, technology, engineering and medical communities in the formulation and implementation of U.S. foreign policy.[58][59] The Fellows (as they are called, if chosen for this program) are paid around $50,000 during the program and can earn special bonuses of up to $10,000. The whole point of this program is so that these Fellows will know the ins and outs of the Department of State/USAID to help with the daily functioning.[60] There is no one winner every year rather it's a program that you apply for and follow a process that starts in August and takes a full year to learn the final results of your ranking. It isn't solely based on achievement alone but intelligence and writing skills that have to show that you encompass all of what the committee is looking for. First you start with the online application then you start to write your curriculum vitae which explains more about yourself and your education and job experience then you move onto your statement of interest and essay where you have your common essay and your briefing memo. Finally you wrap up with letters of recommendations and letters of nominations to show that you are not the only person who believes that they should be a part of this program.

Franklin Fellows Program

The Franklin Fellows Program was established in 2006 by the DoS to bring in mid-level executives from the private sector and non-profit organizations to advise the Department and to work on projects.[61] Fellows may also work with other government entities, including the Congress, White House, and executive branch agencies, including the Department of Defense, Department of Commerce, and Department of Homeland Security. The program is named in honor of Benjamin Franklin, and aims to bring mid-career professionals to enrich and expand the Department's capabilities. Unlike the Jefferson Science Fellows Program this is based on volunteer work as you do not get paid to be a part of this. Rather you have sponsors or you contribute your own money in order to fulfill what it will take to do the year long program. The more seniority you have in this program determines what kind of topics you work on and the priority that the issues are to the country. Although the bottom line is that the other Fellows are the ones with the final say of where you are placed however they try to take into account where you would like to be placed.[62]

Diplomats in Residence

Diplomats in Residence are career Foreign Service Officers and Specialists located throughout the U.S. who provide guidance and advice on careers, internships, and fellowships to students and professionals in the communities they serve. Diplomats in Residence represent 16 population-based regions that encompass the United States.[63]

Military components

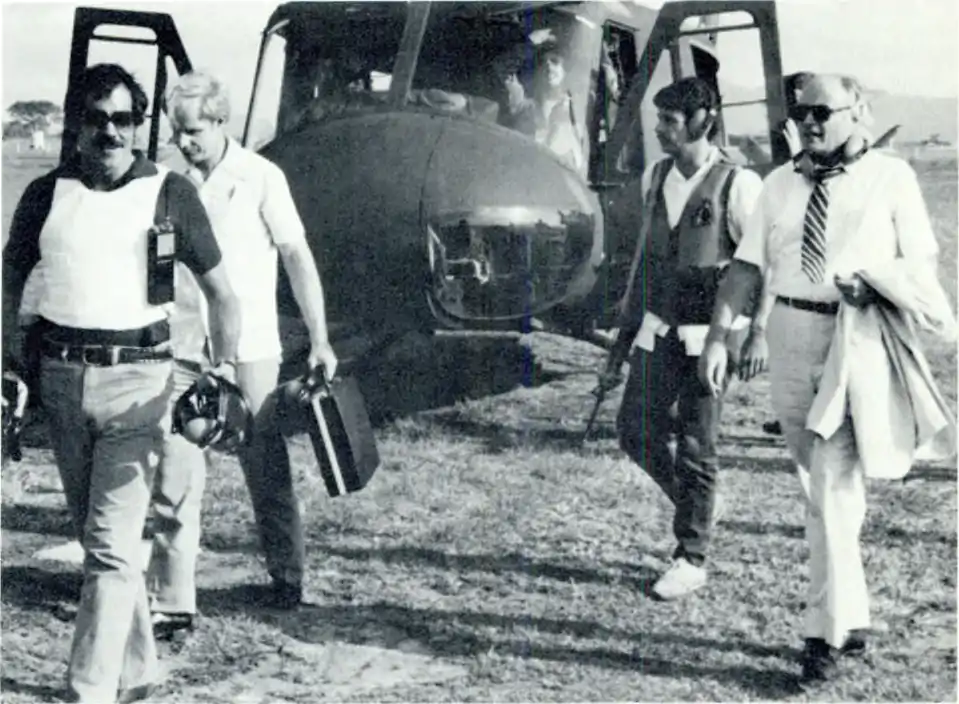

Department of State Air Wing

In 1978, the Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) formed an office to use excess military and government aircraft for support of the counter-narcotics operations of foreign states. The first aircraft used was a crop duster used for eradication of illicit crops in Mexico in cooperation with the local authorities. The separate Air Wing was established in 1986 as use of aviation assets grew in the war on drugs.[64]

The aircraft fleet grew from crop spraying aircraft to larger transports and helicopters used to support ground troops and transport personnel. As these operations became more involved in direct combat, a further need for search and rescue and armed escort helicopters was evident. Operations in the 1980s and 1990s were primarily carried out in Colombia, Guatemala, Peru, Bolivia and Belize. Many aircraft have since been passed on to the governments involved, as they became capable of taking over the operations themselves.

Following the September 11 attacks and the subsequent War on Terror, the Air Wing went on to expand its operations from mainly anti-narcotics operations to also support security of United States nationals and interests, primarily in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Safe transports for various diplomatic missions were undertaken, requiring the acquisition of larger aircraft types, such as Sikorsky S-61, Boeing Vertol CH-46, Beechcraft King Air and De Haviland DHC-8-300. In 2011, the Air Wing was operating more than 230 aircraft around the world, the main missions still being counter narcotics and transportation of state officials.[64]

Naval Support Unit: Department of State

In 1964, at the height of the Cold War, Seabees were assigned to the State Department after listening devices were found in the Embassy of the United States in Moscow;[66] this initial unit was called the "Naval Mobile Construction Battalion FOUR, Detachment November".[67] The U.S. had just constructed a new embassy in Warsaw, and the Seabees were dispatched to locate "bugs". This led to the creation of the Naval Support Unit in 1966, which was made permanent two years later.[68][69] That year William Darrah, a Seabee of the support unit, is credited with saving the U.S. Embassy in Prague, Czechoslovakia from a potentially disastrous fire.[70] In 1986, "as a result of reciprocal expulsions ordered by Washington and Moscow" Seabees were sent to "Moscow and Leningrad to help keep the embassy and the consulate functioning".[71]

The Support Unit has a limited number of special billets for select NCOs, E-5 and above. These Seabees are assigned to the Department of State and attached to Diplomatic Security.[72][66] Those chosen can be assigned to the Regional Security Officer of a specific embassy or be part of a team traveling from one embassy to the next. Duties include the installation of alarm systems, CCTV cameras, electromagnetic locks, safes, vehicle barriers, and securing compounds. They can also assist with the security engineering in sweeping embassies (electronic counter-intelligence). They are tasked with new construction or renovations in security sensitive areas and supervise private contractors in non-sensitive areas.[73] Due to Diplomatic protocol the Support Unit is required to wear civilian clothes most of the time they are on duty and receive a supplemental clothing allowance for this. The information regarding this assignment is very scant, but State Department records in 1985 indicate Department security had 800 employees, plus 1,200 Marines and 115 Seabees.[74] That Seabee number is roughly the same today.[75]

Expenditures

In FY 2010 the Department of State, together with "Other International Programs" (such as USAID), had a combined projected discretionary budget of $51.7 billion.[76] The United States Federal Budget for Fiscal Year 2010, entitled 'A New Era of Responsibility', specifically 'Imposes Transparency on the Budget' for the Department of State.[76]

The end-of-year FY 2010 DoS Agency Financial Report, approved by Secretary Clinton on November 15, 2010, showed actual total costs for the year of $27.4 billion.[77] Revenues of $6.0 billion, $2.8 billion of which were earned through the provision of consular and management services, reduced total net cost to $21.4 billion.[77]

Total program costs for 'Achieving Peace and Security' were $7.0 billion; 'Governing Justly and Democratically', $0.9 billion; 'Investing in People', $4.6 billion; 'Promoting Economic Growth and Prosperity', $1.5 billion; 'Providing Humanitarian Assistance', $1.8 billion; 'Promoting International Understanding', $2.7 billion; 'Strengthening Consular and Management Capabilities', $4.0 billion; 'Executive Direction and Other Costs Not Assigned', $4.2 billion.[77]

Audit of expenditures

The Department of State's independent auditors are Kearney & Company.[78] Since in FY 2009 Kearney & Company qualified its audit opinion, noting material financial reporting weaknesses, the DoS restated its 2009 financial statements in 2010.[78] In its FY 2010 audit report, Kearney & Company provided an unqualified audit opinion while noting significant deficiencies, of controls in relation to financial reporting and budgetary accounting, and of compliance with a number of laws and provisions relating to financial management and accounting requirements.[78] In response the DoS Chief Financial Officer observed that "The Department operates in over 270 locations in 172 countries, while conducting business in 150 currencies and an even larger number of languages ... Despite these complexities, the Department pursues a commitment to financial integrity, transparency, and accountability that is the equal of any large multi-national corporation."[79]

Central Foreign Policy File

Since 1973 the primary record keeping system of the Department of State is the Central Foreign Policy File. It consists of copies of official telegrams, airgrams, reports, memorandums, correspondence, diplomatic notes, and other documents related to foreign relations.[80] Over 1,000,000 records spanning the time period from 1973 to 1979 can be accessed online from the National Archives and Records Administration.[81]

Freedom of Information Act processing performance

In the 2015 Center for Effective Government analysis of 15 federal agencies which receive the most Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) (using 2012 and 2013 data), the State Department was the lowest performer, earning an "F" by scoring only 37 out of a possible 100 points, unchanged from 2013. The State Department's score was dismal due to its extremely low processing score of 23 percent, which was completely out of line with any other agency's performance.[82]

See also

Notes

- For a short period, during which a yellow fever epidemic ravaged the city, it resided in the New Jersey State House in Trenton, New Jersey

- Except for a period between September 1814 to April 1816, during which it occupied a structure at G and 18th Streets NW while the Treasury Building was repaired.

References

- Foreign Service local employees."What We Do: Mission". Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Department of State. "Congressional Budget Justification: Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs" (PDF). state.gov. US government. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (June 18, 2004). "Glossary of Acronyms". 2001-2009.state.gov.

- "U.S. Department of State". United States Department of State. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "A New Framework for Foreign Affairs". A Short History of the Department of State. U.S. Department of State. March 14, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- "Cabinets and Counselors: The President and the Executive Branch" (1997). Congressional Quarterly. p. 87.

- https://www.politico.com/news/2021/01/26/antony-blinken-confirmed-secretary-of-state-462660

- Meredith, Sam (November 27, 2019). "China has overtaken the US to have the world's largest diplomatic network, think tank says". CNBC. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "1 United States Statutes at Large, Chapter 4, Section 1".

- "22 U.S. Code § 2651 - Establishment of Department". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "United States Statutes at Large, First Congress, Session 1, Chapter 14". Archived from the original on June 23, 2012.

- Bureau of Public Affairs. "1784–1800: New Republic". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- "Department History - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs (February 4, 2005). "Frequently Asked Historical Questions". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "Rogers Act". u-s-history.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "Department History - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "Hillary Clinton Launches E-Suggestion Box..'The Secretary is Listening' – ABC News". Blogs.abcnews.com. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Lipowicz, Alice (April 22, 2011). "State Department to launch "Corridor" internal social network – Federal Computer Week". Fcw.com. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- "Peering down the Corridor: The New Social Network's Features and Their Uses | IBM Center for the Business of Government". Businessofgovernment.org. May 5, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- "Remarks at the New York University Commencement Ceremony, Hillary Rodham Clinton". Office of Website Management, Bureau of Public Affairs. U.S. State Department. May 13, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- "The Most Desirable Employers". BusinessWeek. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

- "21st Century Statecraft". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- "Talking 21st Century Statecraft". thediplomat.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- DuPre, Carrie; Williams, Kate (May 1, 2011). "Undergraduates' Perceptions of Employer Expectations". Journal of Career and Technical Education. 26 (1). doi:10.21061/jcte.v26i1.490. ISSN 1533-1830.

- This complex is also known as the "Potomac Annex".

- Sernovitz, Daniel J. "Boston Firm Picked for State Department Consolidation". Washington Business Journal. January 14, 2014. Accessed January 14, 2014.

- Kori N. Schake, State of disrepair: Fixing the culture and practices of the State Department. (Hoover Press, 2013).

- United States Department of State, Bureau of Diplomatic Security (July 2011). "Diplomatic and Consular Immunity: Guidance for Law Enforcement and Judicial Authorities" (PDF). United States Department of State. p. 15. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- William J. Burns, "The Lost Art of American Diplomacy: Can the State Department Be Saved." Foreign Affairs 98 (2019): 98+.

- Gill, Cory R. (May 18, 2018). U.S. Department of State Personnel: Background and Selected Issues for Congress (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved June 23, 2018.

- "Workforce Statistics". 2009-2017.state.gov.

- "Under Secretary for Management". State.gov. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- "1 FAM 360 Bureau of Medical Services (MED)". fam.state.gov. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- "Bureau of Medical Services". State.gov. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Pincus, Erica (December 22, 2014). "The Science and Technology Adviser to the U.S. Secretary of State". Science & Diplomacy. 3 (4).

- "A New Center for Global Engagement". U.S. Department of State.

- McManus, Doyle (November 4, 2018). "Almost Half the Top Jobs in Trump's State Department Are Still Empty". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- Rosiak, Luke (November 26, 2019). "Investigation: Vacancies in Trump's State Department Allow Career Bureaucrats to Take Charge". The National Interest. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- "Buildings of the Department of State - Buildings - Department History - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- Plischke, Elmer. U.S. Department of State: A Reference History. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999, p. 45.

- Tinkler, Robert. James Hamilton of South Carolina. Baton Rouge, La.: Louisiana State University Press, 2004, p. 52.

- Burke, Lee H. and Patterson, Richard Sharpe. Homes of the Department of State, 1774–1976: The Buildings Occupied by the Department of State and Its Predecessors. Washington, D.C.: US. Government Printing Office, 1977, p. 27.

- Michael, William Henry. History of the Department of State of the United States: Its Formation and Duties, Together With Biographies of Its Present Officers and Secretaries From the Beginning. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1901, p. 12.

- Burke and Patterson, p. 37.

- Burke and Patterson, 1977, p. 41.

- Plischke, p. 467.

- Sernovitz, Daniel J. (October 10, 2014)."State Department's Truman Building to Get Multimillion-Dollar Makeover". Washington Business Journal.

- "CNN.com - State Department headquarters named for Harry S. Truman - September 22, 2000". December 8, 2004. Archived from the original on December 8, 2004. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- "Definition of Foggy Bottom". The American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- Alex Carmine. (2009.) Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol: The Ultimate Unauthorized and Independent Reading Guide, Punked Books, p. 37. ISBN 9781908375018.

- Joel Mowbray. (2003.) Dangerous Diplomacy: How the State Department Threatens America's Security, Regnery Publishing, p. 11. ISBN 9780895261106.

- "ETA Grant Application Statistics". us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- "Study/Research Grant Application Statistics". us.fulbrightonline.org. Archived from the original on December 25, 2015. Retrieved December 25, 2015.

- "Fulbright Program Fact Sheet" (PDF). U.S. Department of State.

- "IIE Programs". Institute of International Education. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- "53 Fulbright Alumni Awarded the Nobel Prize" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 8, 2014.

- "Notable Fulbrighters". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on October 16, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- "MacArthur Supports New Science and Security Fellowship Program at U.S. Department of State". MacArthur Foundation. October 8, 2002. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "Jefferson Science Fellowship Program – U.S. Department of State". Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "About the Jefferson Science Fellowship". sites.nationalacademies.org. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- (PDF). March 2, 2012 https://web.archive.org/web/20120302094944/http://www.lmdulye.com/oldp/october07/print/AlumniCorner1.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Franklin Fellows Program – Careers". careers.state.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- "Diplomats in Residence". careers.state.gov. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- "US Department of State Magazine, May 2011" (PDF).

- "The Critical Mission of Providing Diplomatic Security: Through the Eyes of a U.S. Navy Seabee". DipNote.

- "This Week in Seabee History (Week of April 16)".

- History of the Bureau of Diplomatic Security of the United States Department of State, Chapter 5 – Spies, Leaks, Bugs, and Diplomats, written by State Department Historian's Office, pp. 179–80, U.S. State Department

- "Chapter 1, US Navy Basic Military Requirements for Seabees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Department of State, Justice, Commerce, the Judiciary and related Agencies appropriations for 1966, Hearings...Dept of State, p. 6 M

- August 26, This Week in Seabee History (August 26 – September 1), by Dr. Frank A. Blazich Jr, NHHC, Naval Facilities Engineering Command (NAVFAC), Washington Navy Yard, DC

- "Washington to Send a U.S. Support Staff to Missions in Soviet Union", Bernard Gwertzman, The New York Times, October 25, 1986

- "Protecting Information". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "US Navy Basic Military Requirements for Seabees, Chapter 1, p. 11" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 30, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Barker, J. Craig (2016). The Protection of Diplomatic Personnel. New York: Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-317-01879-7.

- "From bugs to bombs, little-known Seabee unit protects US embassies from threats", Stars and Stripes, April 26, 2018,

- "United States Federal Budget for Fiscal Year 2010 (vid. pp.88,89)" (PDF). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- "United States Department of State FY 2010 Agency Financial Report (vid. pp.3,80)" (PDF). US Department of State. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- "United States Department of State FY 2010 Agency Financial Report (vid. p.62ff.)" (PDF). US Department of State. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- "United States Department of State FY 2010 Agency Financial Report (vid. p.76.)" (PDF). US Department of State. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- "FAQ: Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State Central Foreign Policy File, 1973–1976" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. August 6, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- "What's New in AAD: Central Foreign Policy Files, created, 7/1/1973 – 12/31/1976, documenting the period 7/1/1973 ? – 12/31/1976". National Archives and Records Administration. 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- Making the Grade: Access to Information Scorecard 2015 March 2015, 80 pages, Center for Effective Government, retrieved March 21, 2016

Primary sources

- The Foreign Service Journal, complete issues of the Consular Bureau's monthly news magazine, 1919-present

- @StateDept — official departmental twitter account

- State.gov — official departmental website

- 2017—2021 State.gov — Archived website and diplomatic records — Trump adminstration

- 2009—2017 State.gov — Archived website and diplomatic records — Obama administration

Further reading

- Allen, Debra J. Historical Dictionary of US Diplomacy from the Revolution to Secession (Scarecrow Press, 2012), 1775–1861.

- Bacchus, William I. Foreign Policy and the Bureaucratic Process: The State Department’s Country Director System (1974

- Campbell, John Franklin. The Foreign Affairs Fudge Factory (1971)

- Colman, Jonathan. "The ‘Bowl of Jelly’: The us Department of State during the Kennedy and Johnson Years, 1961–1968." Hague Journal of Diplomacy 10.2 (2015): 172-196. =online

- Ronan Farrow (2018). War on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393652109.

- Keegan, Nicholas M. US Consular Representation in Britain Since 1790 (Anthem Press, 2018).

- Kopp, Harry W. Career diplomacy: Life and work in the US Foreign Service (Georgetown University Press, 2011).

- Krenn, Michael. Black Diplomacy: African Americans and the State Department, 1945-69 (2015).* Leacacos, John P. Fires in the In-Basket: The ABC’s of the State Department (1968)

- McAllister, William B., et al. Toward "Thorough, Accurate, and Reliable": A History of the Foreign Relations of the United States Series (US Government Printing Office, 2015), a history of the publication of US diplomatic documents online

- Plischke, Elmer. U.S. Department of State: A Reference History (Greenwood Press, 1999)

- Schake, Kori N. State of disrepair: Fixing the culture and practices of the State Department. (Hoover Press, 2013).

- Simpson, Smith. Anatomy of the State Department (1967)

- Warwick, Donald P. A Theory of Public Bureaucracy: Politics, Personality and Organization in the State Department (1975).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Department of State. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about "United States Department of State". |

| Library resources about United States Department of State |

- Official website

- Department of State on USAspending.gov

- U.S. Department of State in the Federal Register

- Frontline Diplomacy: The Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training from the Library of Congress

- Works by or about United States Department of State at Internet Archive (historic archives)