Usage of electronic cigarettes

Since the introduction of electronic cigarettes to the market in 2003,[1] their global usage has risen exponentially.[2] In 2011, there were approximately seven million adult e-cigarette users globally to 41 million of them in 2018.[3] Awareness and use of e-cigarettes greatly increased over the few years leading up to 2014, particularly among young people and women in some parts of the world.[4] Since their introduction vaping has increased in the majority of high-income countries.[5] E-cigarette use in the US and Europe is higher than in other countries,[6] except for China which has the greatest number of e-cigarette users.[7] Growth in the UK as of January 2018 had reportedly slowed since 2013.[8] The growing frequency of e-cigarette use may be due to heavy promotion in youth-driven media channels, their low cost, and the belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes, according to a 2016 review.[9] E-cigarette use may also be increasing due to the consensus among several scientific organizations that e-cigarettes are safer (although not without risk) compared to combustible tobacco products.[10] E-cigarette use also appears to be increasing at the same time as a rapid decrease in cigarette use in many countries,[11] suggesting that e-cigarettes may be displacing traditional cigarettes.

The prevalence of vaping among adolescents is increasing worldwide.[12] There is substantial variability in vaping in youth worldwide across countries.[13] Over the years leading up to 2017, vaping among adolescents has grown every year since these devices were first introduced to the market.[14] There appears to be an increase of one-time e-cigarette use among young people worldwide.[15] Most e-cigarette users among youth have never smoked.[16] Many youths who use e-cigarettes also smoke traditional cigarettes.[17] While some studies find associations between the use of e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes,[18][19][20] studies that estimate this relationship using causal methods from health economics have concluded the opposite.[11][21] In general, those studies tend to use robust quasi-experimental econometrics methods along with policy variation to predict e-cigarette use rather than relying on individual selection. Using policy variation is critical as it avoids the methodological challenge that many e-cigarette users are high-risk individuals that would have otherwise smoked cigarettes and may now use e-cigarettes first to “test the waters” before transitioning to their a-priori preferred choice of cigarettes. Therefore, using policy variation is an improvement over much of the current e-cigarette research to date that fails to separate the causal effect of e-cigarette use from preferences to gradually increase the riskiness of tobacco product use over time. These studies using policy variation generally conclude that e-cigarettes are displacing smoking, which aligns with cigarette use rates falling while e-cigarette use rates are rising.[22][23][24][25] This contrasts with much of the literature not using policy variation and spuriously concluding that e-cigarettes are gateways to subsequent cigarette use, which does not align with observed patterns of tobacco use.[26]

There are varied reasons for e-cigarette use.[6] Most users' motivation is related to trying to quit smoking, but a large proportion of use is recreational.[6] Adults cite predominantly three reasons for trying and using e-cigarettes: as an aid to smoking cessation, as a safer alternative to traditional cigarettes, and as a way to conveniently get around smoke-free laws.[27] Many users vape because they believe it is healthier than smoking for themselves or bystanders.[28] Usually, only a small proportion of users are concerned about the potential adverse health effects.[28] Seniors seem to vape to quit smoking or to get around smoke‐free policies.[29] There appears to be a hereditary component to tobacco use, which probably plays a part in transitioning of e-cigarette use from experimentation to routine use.[30] The introduction of e-cigarettes has given cannabis smokers a different way of inhaling cannabinoids.[31] Recreational cannabis users can individually "vape" deodorized or flavored cannabis extracts with minimal annoyance to the people around them and less chance of detection, known as "stealth vaping".[31]

Use

Frequency

Since their introduction to the market in 2003,[1] global usage of e-cigarettes has risen exponentially.[2] By 2013, there were several million users globally.[32] In 2011 there were approximately seven million adult e-cigarette users globally in 2011 to 41 million of them in 2018.[3] Awareness and use of e-cigarettes greatly increased over the few years leading up to 2014, particularly among young people and women in some parts of the world.[4] A 2013 four-country survey found there was generally greater awareness among white adult smokers compared with non-white ones.[33] Vaping is increasing in the majority of high-income countries.[5] E-cigarette use in the US and Europe is higher than in other countries,[6] except for China which has the greatest number of e-cigarette users.[7] Growth in the US had reportedly slowed in 2015, lowering market forecasts for 2016.[34] Growth in the UK as of January 2018 had reportedly slowed since 2013.[8] The growing frequency of e-cigarette use may be due to heavy promotion in youth-driven media channels, their low cost, and the belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes, according to a 2016 review.[9] In 2018, it was estimated that there were 35 million e-cigarette users globally (including heat-not-burn tobacco products), with this rapid growth predicted to continue.[35]

Surveys in 2010 and 2011 suggested that adults with higher incomes were more likely to have heard of e-cigarettes, but those with lower incomes may have been more likely to try them.[36] Most users had a history of smoking regular cigarettes, while results by race were mixed.[36] At least 52% of smokers or ex-smokers have used an e-cigarette.[37] Of smokers who have, less than 15% become everyday e-cigarette users.[38] Though e-cigarette use among those who have never smoked is very low, it continues to rise.[39] Daily vapers are typically recent former smokers.[40] E-cigarettes are commonly used among non-smokers.[41] This includes young adult non-smokers.[41] Vaping is the largest among adults between 18 and 24 years of age, and use is the largest among adults who do not have a high school diploma.[42] Young adults who vape but do not smoke are more than twice as likely to intend to try smoking than their peers who do not vape.[16] A worldwide survey of e-cigarette users conducted in 2014 found that only 3.5% of respondents used liquid without nicotine.[43]

Greater than 10 million people vape daily, as of 2018.[44] Everyday use is common among e-cigarette users.[28] E-cigarette users mostly keep smoking traditional cigarettes.[17] Adults often vape to replace tobacco.[36] Most vapers still use nicotine liquids after stopping smoking for several months.[45] Most e-cigarette users are middle-aged men who also smoke traditional cigarettes, either to help them quit or for recreational use.[6] Older people are more likely to vape for quitting smoking than younger people.[46] Men were found to use higher nicotine doses, compared with women who were vaping.[47] Among young adults e-cigarette use is not regularly associated with trying to quit smoking.[36] The research indicates that the most common way people try to quit smoking in the UK is with e-cigarettes.[48]

Dual use of e-cigarettes and traditional tobacco is common.[49] Dual use of e-cigarettes with cigarettes is the most frequent pattern.[50] One-time e-cigarette use seems to be higher in people with greater levels of educational achievement.[51] Women smokers who are poorer and did not finish high school are more likely to have tried vaping at least once.[52] Vaping is increasing among people with cancer who are frequent smokers.[53]

Gateway or Displacement theory

In the context of drugs, the gateway hypothesis predicts that the use of less deleterious drugs can lead to a future risk of using more dangerous hard drugs or crime.[54] Some research provides suggestive evidence that vaping is a "gateway" to smoking by examining how e-cigarette use in one period predicts cigarette use in another period.[55] However, under the common liability model, some have suggested that any favorable relation between vaping and starting smoking is a result of common risk factors.[56] Health economics research using e-cigarette policy variation to examine use of cigarettes independent of common sources of confounding factors such as personal risk preferences generally finds that vaping is an "exit ramp" from, or displacing, smoking.[57][58][59][60][61]

Additionally, descriptive evidence of e-cigarette and cigarette use patterns in the United States suggests that e-cigarettes are displacing cigarettes. The rise in e-cigarette use has coincided with a sharp decline in cigarette use for both teenagers and adults. For example, youth current cigarette smoking, at 5.8% in 2019, has declined by 63.3%[62] from 2011 to 2019 (compared to only a 17.4% decline[63] from 2003-2011 when e-cigarettes were not widely used). Over the same time period youth current e-cigarette use rose from 1.5% in 2011 to 27.5% in 2019. E-cigarettes are not as regularly used among adults, with adult current use[64] at 2.8% in 2017. The adult current smoking rate, at 13.7% in 2018, has declined by a more modest 27.9% between 2011[65] to 2018[66] compared to the more rapid 63.3% decline for youth current cigarette use.

There is evidence for young adults and youth that e-cigarette use is correlated with an increased change of one-time traditional cigarette use.[10] The evidence indicates that the e-cigarettes such as Juul that can provide greater levels of nicotine could increase the chance for users to transition from vaping to smoking cigarettes.[68] Ethical concerns have been raised about minors' e-cigarette use and the potential to weaken cigarette smoking reduction efforts.[69] Protective factors from using e-cigarettes were better ability to read and write, exercising, being female, and not smoking.[70] Studies indicate vaping is correlated with traditional cigarettes and cannabis use.[68] This includes impulsive and sensation seeking personality types or exposure to people who are sympathetic with smoking and relatives.[56] A 2014 review using animal models found that nicotine exposure may increase the likelihood to using other drugs, independent of factors associated with a common liability.[notes 1][72] The gateway theory, in relation to using nicotine, has also been used as a way to propose that using tobacco-free nicotine is probably going to lead to using nicotine via tobacco smoking, and therefore that vaping by non-smokers, and especially by children, may result in smoking independent of other factors associated with starting smoking.[72] Some see the gateway model as a way to illustrate the potential risk-heightening effect of vaping and going on to use combusted tobacco products.[73]

There is concern regarding that the accessibility of e-liquid flavors could lead to using additional tobacco products among non-smokers.[74] It is argued to implement the precautionary principle because vaping by non-smokers may lead to smoking.[75] There is a concern with the possibility that non-smokers as well as children may start nicotine use with e-cigarettes at a rate higher than anticipated than if they were never created.[76] In certain cases, e-cigarettes might increase the likelihood of being exposed to nicotine itself, especially for never-nicotine users who start using nicotine products only as a result of these devices.[77] A 2015 review concluded that "Nicotine acts as a gateway drug on the brain, and this effect is likely to occur whether the exposure is from smoking tobacco, passive tobacco smoke or e-cigarettes."[78] Because those with mental illness are highly predisposed to nicotine addiction, those who try e-cigarettes may be more likely to become dependent, raising concerns about facilitating a transition to combustible tobacco use.[79] Even if an e-cigarette contains no nicotine, the user mimics the actions of smoking.[80] This may renormalize tobacco use in the general public.[80] Normalization of e-cigarette use may lead former cigarette smokers to begin using them, thereby reinstating their nicotine dependence and fostering a return to tobacco use.[81] There is a possible risk of re-normalizing of tobacco use in areas where smoking is banned.[80] Government intervention is recommended to keep children safe from the re-normalizing of tobacco, according to a 2017 review.[14]

The "catalyst model" suggests that vaping may proliferate smoking in minors by sensitizing minors to nicotine with the use of a type of nicotine that is more pleasing and without the negative attributes of regular cigarettes.[82] A 2016 review, based on the catalyst model, "indicate that the perceived health risks, specific product characteristics (such as taste, price and inconspicuous use), and higher levels of acceptance among peers and others potentially make e-cigarettes initially more attractive to adolescents than tobacco cigarettes. Later, increasing familiarity with nicotine could lead to the reevaluation of both electronic and tobacco cigarettes and subsequently to a potential transition to tobacco smoking."[12]

A 2016 UK Royal College of Physicians report stated that the concerns regarding vaping leading to smoking in young people are unfounded.[83] They stated that it more likely occurs from a common liability to using both products.[83] They went on to state, "Renormalisation concerns, based on the premise that e-cigarette use encourages tobacco smoking among others, also have no basis in experience to date."[84] A 2015 Public Health England (PHE) report found no evidence e-cigarettes increase adult or youth smoking.[85] They stated that it is possible e-cigarettes has contributed to the drop in smoking.[85] In 2018, other scientific organizations, such as the Forum of International Respiratory Societies, disagrees.[86]

Pregnancy

E-cigarette use was also rising among women, including women of childbearing age as of 2014,[87] but the rate of use during pregnancy is unknown.[88] Many woman still vape during pregnancy because of their perceived safety in comparison with tobacco.[29] In one of the few studies identified, a 2015 survey of 316 pregnant women in a Maryland clinic found that the majority had heard of e-cigarettes, 13% had ever used them, and 0.6% were current daily users.[89] These findings are of concern because the dose of nicotine delivered by e-cigarettes can be as high or higher than that delivered by traditional cigarettes.[89] The rate of e-cigarette use among pregnant adolescents is unknown.[89]

Descriptive evidence on vaping prevalence among pregnant women provides additional confirmation of such women’s potential interest in e-cigarettes. Data from two states in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment System (PRAMS) show that in 2015—roughly the mid-point of the study period—10.8% of the sample used e-cigarettes in the three months prior to the pregnancy while 7.0%, 5.8%, and 1.4% used these products respectively at the time of the pregnancy, in the first trimester, and at birth.[90] According to National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from 2014 to 2017, 38.9% of pregnant smokers used e-cigarettes compared to only 13.5% of non-pregnant, reproductive age women smokers.[91] A health economic study found that passing an e-cigarette minimum legal sale age laws in the United States increased teenage prenatal smoking by 0.6 percentage points and had no effect on birth outcomes.[92]

International

Among current and former smokers who have vaped at least once were reported in Canada, the UK, France, Belgium, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, Greece (22.4% in 2012), Malta (16.7% in 2012), Portugal (17.0% in 2012), Slovenia (20.3% in 2012), Spain (10.9% in 2012), Cyprus (23.6% in 2012), Denmark (36.3% in 2012), Slovakia (7.9% in 2012), the Czech Republic (34.3% in 2012), Ireland (12.1% in 2012), Latvia (23.9% in 2012), Lithuania (11.8% in 2012), Finland (20.5% in 2012), Sweden (12.4% in 2012), Estonia (22.3% in 2012), Hungary (22.3% in 2012), Bulgaria (31.1% in 2012), Romania (22.2% in 2012), Australia (2.0–20.0% in 2010–2013), Italy (5.6% in 2013), Poland (31.0% in 2012), Malaysia (19% in 2011), Brazil (8% in 2013), Mexico (4% in 2011), South Korea (11% in 2010), Brazil (8% in 2013), and China (2% in 2009).[93] In countries where there is not regulation on e-cigarettes, vaping is common in areas where smoking is not permitted.[94] Of the participants 15 and higher in Taiwan in 2015, 2.7% stated to have ever tried an e-cigarette.[95] Of the participants 15 to 65 in Hong Kong in 2014, 2.3% stated to have ever tried an e-cigarette.[95] Of the adult participants in the Republic of Korea in 2013, 6.6% stated to have ever tried an e-cigarette while 1.1% were current e-cigarette users.[95] Of the participants 15 and higher in New Zealand in 2014, 13.1% stated to have ever tried an e-cigarette while 0.8% were current e-cigarette users.[96]

United States

In the US, vaping is normally the highest among young adults and adolescents.[97] In 2016 in the US, there were greater than 2.5 million e-cigarette users.[44] In 2016, 3.2% of US adults were current e-cigarette users.[98] Among current e-cigarette users aged 45 years and older in 2015, most were either current or former regular cigarette smokers, and 1.3% had never been cigarette smokers.[98] In contrast, among current e-cigarette users aged 18–24 years, 40.0% had never been regular cigarette smokers.[98] A 2018 review suggested that e-cigarettes are contributing to the tobacco epidemic by attracting smokers who are interested in quitting but reducing the likelihood of those smokers to quit successfully.[27] This effect maybe reflected in the fact that in 2015 the number of cigarettes consumed in the US was higher than in 2014, the first time cigarette consumption increased since 1973.[27] In the US, as of 2014, 12.6% of adults had used an e-cigarette at least once and about 3.7% were still using them.[99] In 2014, about 3.8% employed adults were e-cigarette users.[100] As of mid-2015 around 10% of American adults are current users of e-cigarettes.[101] In 2014, 1.1% of adults were daily users.[102] In 2014 in the US, 93% of e-cigarette users continued to smoke cigarettes.[27] Non-smokers and former smokers who had quit more than four years earlier were extremely unlikely to be current users.[102] Former smokers who had recently quit were more than four times as likely to be daily users as current smokers.[102] Experimentation was more common among younger adults, but daily users were more likely to be older adults.[102] Cigarettes and e-cigarettes are most frequently used together for adults and youth utilizing more than one tobacco product.[74] More generally, there is supportive evidence that e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes are economic substitutes, and that e-cigarettes are displacing smoking rather than causing more smoking through a gateway effect.[103][104][105][106][107] Also, it is interesting to note that 15% of individuals with mental illness have tried vaping.[108]

United States youth

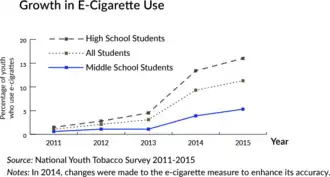

The recent decline in smoking has accompanied a rapid growth in the use of alternative nicotine products among youth and young adults.[109] E-cigarettes are the most frequently used tobacco product among US youths.[110] In the US, youth are more likely than adults to use e-cigarettes.[98] In the US among youth, vaping is the most in boys, non-Hispanic white youth and Hispanic youth.[97] A considerable increase in e-cigarette use among US youths, coupled with no change in use of other tobacco products during 2017–2018, has erased recent progress in reducing overall tobacco product use among youths.[111] Among both US high school and middle school students, current use of e-cigarettes increased considerably between 2017 and 2018, reaching epidemic proportions, according to the US Surgeon General; approximately 1.5 million more youths currently used e-cigarettes in 2018 (3.6 million) compared with 2017 (2.1 million).[111] However, no significant change in current use of combustible tobacco products, such as cigarettes and cigars, was observed in recent years or during 2017–2018.[111] This recent increase in e-cigarette use among youths is consistent with observed increases in sales of the e-cigarette Juul, a USB-shaped e-cigarette device with a high nicotine content that can be used discreetly and is available in flavors that can appeal to youths.[111] This indicates that e-cigarettes were the driver of the observed increase in any tobacco product use.[111]

Among American youth who had tried a vaporizer at least once, 65-66% most recently tried flavoring in 12th, in 10th, and in 8th grade in 2017.[112] Vaping with nicotine was approximately 20% in 12th and 10th grade and for 8th graders 13%, according to data from the Monitoring the Future in 2017.[112] E-cigarettes were the most commonly used tobacco product among US middle school and high school students in 2016.[113] In 2016, more than 2 million US middle and high school students used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days, including 4.3% of middle school students and 11.3% of high school students.[98] In 2015, 58.8% of high school students who were current users of combustible tobacco products were also current users of e-cigarettes.[114] 1 in 6 high school students used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days in 2015.[115] Between 2011 and 2015, vaping among minors increased 900 percent.[116] In the US, vaping among youth exceeded smoking in 2014.[117] As of 2014, up to 13% of American high school students had used them at least once in the last month.[118]

Youth are attracted by e-cigarettes’ novelty, the perception that they are harmless or less harmful than cigarettes, and the thousands of flavors (e.g., fruit, chocolate, peanut butter, bubble gum, gummy bear, among others).[27] As a result, youth e-cigarette use in the US doubled or tripled every year between 2011 and 2014.[27] At the same time that e-cigarette use was increasing, cigarette smoking among youth declined, leading some to suggest that e-cigarettes were replacing traditional cigarettes among youth and are contributing to declines in youth smoking.[27] At least through 2014, however, e-cigarettes had no detectable effect on the decline in cigarette smoking among US adolescent.[27] Between 2013 and 2014, vaping among students tripled.[119] In 2013 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated that around 160,000 students between 2011 and 2012 who had tried vaping had never smoked cigarettes.[109] E-cigarette use among never-smoking youth in the US correlates with elevated desires to use traditional cigarettes.[49] Teenagers who had used an e-cigarette were more inclined to become smokers than those who had not.[120] In the 2015 Monitoring the Future survey, a majority of students who used e-cigarettes reported using liquid without nicotine the last time they vaped.[121] The majority of youth who vape also smoke.[122] A long-term survey of high school students in Hawaii reported that shifting from never-use to smoking was associated with vaping.[123] A 2010–2011 survey of students at two US high schools found that vapers were more likely to use hookah and blunts than smokers.[124] Among grade 6 to 12 students in the US, the proportion who have tried them rose from 3.3% in 2011 to 6.8% in 2012.[36] Those still vaping over the last month rose from 1.1% to 2.1% and dual use rose from 0.8% to 1.6%.[36] Over the same period, the proportion of grade-6-to-12 students who regularly smoke tobacco fell from 7.5% to 6.7%.[125] The evidence indicates that vaping may promote, instead of impede, the use of traditional cigarettes among US adolescents.[126]

European Union

In 2016 in Europe, there were 7.5 million e-cigarette users.[44] There were an estimated 3.6 million adult users in the UK in 2019.[127] In 2018, regular e-cigarette use in the UK was greater than in other countries in the EU.[128] Regular e-cigarette use in the UK in 2018 was about 2%.[128] In the UK in 2018, e-cigarette use among adults was about 6%.[129] In the UK in 2017, around 2.9 million adults use e-cigarettes.[130] In the UK, user numbers increased from 700,000 in 2012 to 2.6 million in 2015, but use by current smokers remained flat at 17.6% from 2014 into 2015 (in 2010, it was 2.7%).[131] About one in 20 adults in the UK uses e-cigarettes.[132] In the UK in 2015, 18% of regular smokers said they used e-cigarettes and 59% said they had used them in the past.[131] Among those who had never smoked, 1.1% said they had tried them and 0.2% still use them.[131] In 2014 in the UK, 60% e-cigarette users continued to smoke cigarettes.[27] About 60% of all users are smokers and most of the rest are ex-smokers, with negligible numbers of never-smokers.[133] In 2015 figures showed around 2% monthly EC-usage among under-18s, and 0.5% weekly, and despite experimentation, "nearly all those using EC regularly were cigarette smokers".[134] Non-smokers in the UK who vaped are more likely to have smoked later on than people who did not vape.[135]

European Union youth

Public Health England reported that 1.7% of those aged 11–18 years in England had regularly used e-cigarettes in 2018.[136] Regular use was low among those who had never smoked.[136] Those from 11 to 16, one-time e-cigarette use varied from 7-18% of the respondents among the 2015-2016 EU surveys.[137] Regular vaping in young people who have not tried smoking, varied from 0.1% to 0.5% in all EU surveys.[137] In 2016 in the UK, those between 11 and 18 in the UK, 10% reported they have used e-cigarettes at least once or twice.[138] In 2016 in the UK, 2% reported they have vaped more than once a month, including 1% stated they used them every week.[138] A 2016 study found 11–16-year-olds English children exposed to e-cigarette advertisements highlighting flavored, in contrast to flavor-free products, did bring about more appeal to e-cigarettes.[139] In Fife, Scotland in 2013, 19% of 15-year-olds and 10% of 13-year-olds reported they tried e-cigarettes.[140] Both were 3% above that of the typical figures in Scottish for this age group.[140] 10–11-year-olds Welsh never-smokers are more likely to use e-cigarettes if a parent used e-cigarettes.[141] The popularity of vaping is greater among the youth from Central and Eastern Europe than other places in Europe.[142]

France

In France, a 2014 survey estimated between 7.7 and 9.2 million people had tried e-cigarettes and 1.1 to 1.9 million use them on a daily basis.[143] The same survey also found 67% of smokers used e-cigarettes to reduce or quit smoking.[143] Of respondents who indicated they tried e-cigarettes, 9% said they had never smoked tobacco.[143] Of the 1.2% who had recently stopped tobacco smoking at the time of the survey, 84% (or 1% of the population surveyed) credited e-cigarettes as essential in quitting.[143] Approximately greater than 90% of French smokers have vaped.[80] In 2014 in France, 83% e-cigarette users continued to smoke cigarettes.[27]

Australia

Vaping in Australia has risen quickly even with legal barriers to trade of nicotine for non-therapeutic uses.[144] It is unclear whether comparable rises in e-cigarette use as seen in the US are to be anticipated in Australia.[145] In New South Wales in 2014, the frequency of regular e-cigarettes users was 1.3%, with 8.4% had tried them.[145] Around 78,000 people were regular e-cigarettes users in New South Wales; this is generally low than in some other countries, such as the US and the UK.[145] A 2015 online survey found that 97% of participants stated they were daily smokers before trying an e-cigarette.[144] Data on daily vaping in Australia is not available.[146] A 2013 national Australian survey showed that 15.4% of smokers that were 14 years old or higher had vaped at least one time in the prior 12 months, even though selling nicotine liquid is not legal their.[146]

Youth

The prevalence of vaping among adolescents is increasing worldwide.[12] There is substantial variability in vaping in youth worldwide across countries.[13] Over the years leading up to 2017 vaping among adolescents has grown every year since theses devices were first introduced to the market.[14] There appears to be an increase of one-time e-cigarette use among young people worldwide.[15] The frequency of vaping in youth is low.[148] The result of youth e-cigarette use leading to smoking is unclear.[16] Most e-cigarette users among youth have never smoked.[16] Many youth who use e-cigarettes also smoke traditional cigarettes.[17] Some youths who have tried an e-cigarette have never used a traditional cigarette; indicating e-cigarettes may be a starting point for nicotine use.[17] Adolescents who would have not been using nicotine products to begin with are vaping.[149] Twice as many youth vaped in 2014 than also used traditional cigarettes.[150] Vaping seems to be a gateway to using traditional cigarettes in adolescents.[139] Youth who use e-cigarettes are more likely to go on to use traditional cigarettes.[151][152] The evidence suggests that young people who vape are also at greater risk for subsequent long-term tobacco use.[153] E-cigarettes are expanding the nicotine market by attracting low-risk youth who would be unlikely to initiate nicotine use with traditional cigarettes.[27] Data from a longitudinal cohort study of children with alcoholic parents found that adolescents (both middle and late adolescence) who used cigarettes, marijuana, or alcohol were significantly more likely to have ever used e-cigarettes.[89] Adolescents were more likely to initiate vaping through flavored e-cigarettes.[47] Among youth who have ever tried an e-cigarette, a majority used a flavored product the first time they tried an e-cigarette.[89] Vaping is the most common form of tobacco use among youth, as of 2019.[154] There is a greater likelihood of past or present and later cannabis use among youth and young adults who have vaped.[155]

Most youth are not vaping to help them quit tobacco.[36] Adolescent vaping is unlikely to be associated with trying to reduce or quit tobacco.[49] Adolescents who vape but do not smoke are more than twice as likely to intend to try smoking than their peers who do not vape.[16] Vaping is correlated with a higher occurrence of cigarette smoking among adolescents, even in those who otherwise may not have been interested in smoking.[156] Adolescence experimenting with e-cigarettes appears to encourage continued use of traditional cigarettes.[157] A 2015 study found minors had little resistance to buying e-cigarettes online.[117] An emerging concern is that nicotine, fruit flavors, and other e-liquid additives could incite teenagers and children to start using traditional cigarettes.[158] Teenagers may not admit using e-cigarettes, but use, for instance, a hookah pen.[120] As a result, self-reporting may be lower in surveys.[120] Experts suggest that candy-like flavors could lead youths to experiment with vaping.[76] E-cigarette advertisements seen by youth could increase the likelihood among youths to experiment with vaping.[159] A 2016 review found "The reasons for the increasing use of e-cigarettes by minors (persons between 12 and 17 years of age) may include robust marketing and advertising campaigns that showcase celebrities, popular activities, evocative images, and appealing flavors, such as cotton candy."[160] A 2014 survey stated that vapers may have less social and behavioral stigma than cigarette smokers, causing concern that vaping products are enticing youth who may not under other circumstances have used these products.[161] The frequency of vaping is higher in adolescent with asthma than in adolescent who do not have asthma.[162]

Appeal to Young People

Youth and young adults cite a variety of reasons for using e-cigarettes.

These include:

- Use by a friend or family member

- Taste, including the flavors available in e-cigarettes

- The belief that e-cigarettes are less harmful than other tobacco products

- Curiosity

Flavored e-cigarettes are very popular among youth and young adults. In 2014, more than 9 of 10 young adult e-cigarette users said they use e-cigarettes flavored to taste like menthol, alcohol, candy, fruit, chocolate, or other sweets. In 2018, more than 6 of 10 high school students who use e-cigarettes said they use flavored e-cigarettes.

Motivation

There are varied reasons for e-cigarette use.[6] Most users' motivation is related to trying to quit smoking, but a large proportion of use is recreational.[6] Adults cite predominantly three reasons for trying and using e-cigarettes: as an aid to smoking cessation, as a safer alternative to traditional cigarettes, and as a way to conveniently get around smoke-free laws.[27] Some users vape for the enjoyment of the activity.[28] Many e-cigarette users use them because they believe they are safer than traditional cigarettes.[43] People who think they pose less risk than cigarette smoking are more likely to vape.[166] A 2017 report found that smokers who previously vaped and quit though continued smoking, 51.5% believed that vaping is less risky than smoking.[167] In contrast, 90% of former-smokers who vape believed vaping as less risky than cigarettes.[167] A 2017 report found that a minority of the respondents believed that replacing cigarettes with e-cigarettes would be helpful for their health.[168] Many users vape because they believe it is healthier than smoking for themselves or bystanders.[28] Usually, only a small proportion of users are concerned about the potential adverse health effects.[28] Some people say they want to quit smoking by vaping, but others vape to circumvent smoke-free laws and policies, or to cut back on cigarette smoking.[17] 56% of respondents in a US 2013 survey had tried vaping to quit or reduce their smoking.[169] In the same survey, 26% of respondents would use them in areas where smoking was banned.[169] Continuing dual use among smokers is correlated with trying to cut down on smoking and to get around smoking bans, increased desire to quit smoking, and a decreased smoking dependence. Seniors seem to vape to quit smoking or to get around smoke‐free policies.[29] Concerns over avoiding stains on teeth or odor from smoke on clothes in some cases prompted interest in or use of e-cigarettes.[28] Some e-cigarettes appeal considerably to people curious in technology who want to customize their devices.[171] There appears to be a hereditary component to tobacco use, which probably plays a part in transitioning of e-cigarette use from experimentation to routine use.[30]

It is conceivable that former smokers may be tempted to use nicotine again as a result of e-cigarettes, and possibly start smoking again.[77] E-liquid flavors are enticing to a range of smokers and non-smokers.[74] Non-smoking adults tried e-cigarettes due to curiosity, because a relative was using them, or because they were given one.[124] College students often vape for experimentation.[172] Millions of dollars spent on marketing aimed at smokers suggests e-cigarettes are "newer, healthier, cheaper and easier to use in smoke-free situations, all reasons that e-cigarette users claim motivate their use".[173] Marketing messages echo well-established cigarette themes, including freedom, good taste, romance, sexuality, and sociability as well as messages stating that e-cigarettes are healthy, are useful for smoking cessation, and can be used in smoke free environments.[27] These messages are mirrored in the reasons that adults and youth cite for using e-cigarettes.[27] Exposure to e-cigarette advertising influences people to try them.[120]

The belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes could widen their use among pregnant women.[49] If tobacco businesses persuade women that e-cigarettes are a small risk, non-smoking women of reproductive age might start using them and women smoking during pregnancy might switch to their use or use these devices to reduce smoking, instead of quitting smoking altogether.[88] Traditional cigarette users who have not used e-cigarettes had mixed ideas about their possible satisfaction and around a third thought that e-cigarettes might taste bad.[28] Among current e-cigarette users, e-liquid flavor availability is very appealing.[79] They feel or taste similar to traditional cigarettes, and vapers disagreed about whether this was a benefit or a drawback.[28] Some users liked that e-cigarettes resembled traditional cigarettes, but others did not.[28] E-cigarettes users' views about saving money from using e-cigarettes compared to traditional cigarettes are inconsistent.[28] The majority of committed e-cigarette users interviewed at an e-cigarette convention found them cheaper than traditional cigarettes.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Some users stopped vaping due to issues with the devices.[28] Dissatisfaction and concerns over safety can discourage ongoing e-cigarette use.[175] Commonly reported issues with using e-cigarettes were that the devices were hard to refill, the cartridges might leak and that altering the dose was hard.[176] Smokers mainly quit vaping because it did not feel similar to traditional cigarettes, did not aid with cravings, and because they wanted to use them only to know what they were like. A small number of US surveys showed that smokers’ chief reasons for stopping vaping were that they did not feel similar to smoking cigarettes, were too costly, or were only experimenting. A 2016 US survey reported that 77% of current smokers stated e-cigarettes were not as satisfying as traditional cigarettes and quit vaping.[177] E-cigarette do not provide nicotine to the blood as fast as cigarettes and fall short of the throat-hit that cigarettes give, causing some to turn back to traditional cigarettes.[178] In the small number of published studies on reasons for discontinuation of e-cigarette use in young users, adolescent and young adult smokers have cited lack of satisfaction and e-cigarettes' poor taste and cost as reasons for discontinuing.[89] Additional reasons have included negative physical effects (e.g., feeling lightheaded) and loss of interest.[89] In one study of young adults aged 18–35, former and never smokers of traditional cigarettes also cited the idea that e-cigarettes were "bad for their health" as a reason for discontinuation.[89] E-cigarette users have contradictory views about using them to get around smoking bans.[28] Some surveys found that a small percentage of users' motives were to avoid smoking bans, but other surveys found that over 40% of users said they used the device for this reason.[28] The extent to which traditional cigarette users vape to avoid smoking bans is unclear.[28]

E-cigarette marketing with themes of health and lifestyle may encourage youth who do not smoke to try e-cigarettes, as they may believe that e-cigarettes are less harmful and more socially acceptable.[165] This belief may decrease ones concerns relating to nicotine addiction.[165] E-cigarette marketing may entice adults and children.[179] E-cigarette websites regularly contain marketing statements that might appeal to a younger audience.[165] Companies sell an array of flavors like bubblegum, fruit, and chocolate, potentially to entice young people to vape.[142] Adolescent experimenting with e-cigarettes may be related to sensation seeking behavior, and is not likely to be associated with tobacco reduction or quitting smoking.[49] Youth may view e-cigarettes as a symbol of rebellion.[39] Children and adolescents may be tempted by flavored e-cigarettes.[2] Vaping may entice adolescents for many reasons which include the perceived absence of harmful adverse effects.[180] The main reasons youth experimented with e-cigarettes were due to curiosity, flavors, and peer influences.[181] A 2016 study using longitudinal surveys from middle and high school students found flavoring is the second most important factor determining whether students try e-cigarettes, after curiosity and a 2015 study also reported the same finding.[47] E-cigarettes may appeal to youth because of their high-tech design, large assortment of flavors, and easy accessibility online.[164] Tempting candy and fruit flavors e-cigarettes are designed to appeal to youth.[182] The colors, flavors, and scents of e-liquids attract children.[177] E-liquids are sold in a myriad of candy and fruit flavors, such as bubble gum, cherry and chocolate, which may appeal to youth and children.[183] Infants and toddlers could ingest the e-liquid from an e-cigarette device out of curiosity.[184] Flavored tobacco has been shown to have a large market share among youth aged 12 to 17 years, confirming the attractiveness of these products to new and young smokers and their likely contribution to smoking initiation.[185] Infants and children liked sweet and salty flavors more than adults.[186] The bright packaging of e-cigarette products play a part in their allure to young children.[14] The vivid colors, strongly aromatic, and scented flavors for e-liquid bottles are particularly enticing to young children.[187] Among US student respondents to the National Youth Tobacco Survey reporting ever using e-cigarettes in 2016, the most commonly selected reasons for use were used by "friend or family member" (39%), availability of "flavors such as mint, candy, fruit, or chocolate" (31%), and the belief that "they are less harmful than other forms of tobacco such as cigarettes" (17%).[113] The least commonly selected reasons were "they are easier to get than other tobacco products, such as cigarettes" (5%), "they cost less than other tobacco products such as cigarettes" (3%), and "famous people on TV or in movies use them" (2%).[113] A 2016 study of Finnish adolescents found that e-liquids with nicotine were more popular with ever smokers while e-liquids without nicotine were more popular with never smokers.[47]

Teen Beliefs

Youth tobacco use in any form, including e-cigarettes, is unsafe. A recent national survey showed that about 10% of U.S. youth believe e-cigarettes cause no harm, 62% believe they cause little or some harm, and 28% believe they cause a lot of harm when they are used some days but not every day. In 2014, nearly 20% of young adults believe e-cigarettes cause no harm, more than half believe that they are moderately harmful, and 26.8% believe they are very harmful.

Young people who believe e-cigarettes cause no harm are more likely to use e-cigarettes than those who believe e-cigarettes cause a lot of harm.

Source: Adolescent health brief - Harm Perceptions of Intermittent Tobacco Product Use Among U.S. Youth, 2016

Progression

Many users may begin by using a disposable e-cigarette.[148] Users often start with e-cigarettes resembling traditional cigarettes, eventually moving to a later-generation device.[189] Most later-generation e-cigarette users shifted to their present device to get a "more satisfying hit",[189] and users may adjust their devices to provide more vapor for better "throat hits".[52] A 2014 study reported that experienced users preferred rechargeable e-cigarettes over disposable ones.[47] The most commonly used e-cigarettes in the UK are devices with refillable tanks.[129] Most users used either closed systems or open systems, and rarely used both.[47] Women were found to prefer disposable e-cigarettes, and young adults were found to pay more attention to modifiability.[47] Modifiability also was found to increase the probability of initiating e-cigarettes among adolescents.[47]

A 2013 study found that about three-fourths of smokers used a tank system, which allows users to choose flavors and strength to mix their own liquid.[47] Experienced e-cigarette users even ranked the ability to customize as the most important characteristic.[47] Users ranked nicotine strength as an important factor for choosing among various e-cigarettes, though such preference could vary by smoking status, e-cigarette use history, and gender.[47] Non-smokers and inexperienced e-cigarettes users tended to prefer no nicotine or low nicotine e-cigarettes while smokers and experienced e-cigarettes users preferred medium and high nicotine e-cigarettes.[47] There is an abundance of colors, designs, carrying cases, and accessories to accommodate the diversity in personal preferences.[148]

Other uses

The introduction of e-cigarettes has given cannabis smokers a different way of inhaling cannabinoids.[31] E-cigarettes are unlike traditional cannabis cigarettes in several respects.[31] It is assumed that vaporizing cannabinoids at lower temperatures is safer because it produces smaller amounts of toxicants than the hot combustion of a cannabis cigarette.[31] Recreational cannabis users can individually "vape" deodorized or flavored cannabis extracts with minimal annoyance to the people around them and less chance of detection, known as "stealth vaping".[31] While cannabis is not readily soluble in the liquid used for e-cigarettes, recipes containing synthetic cannabinoids which are soluble are available online.[31] Companies also make synthetic cannabinoids liquid cartridges for use in e-cigarettes.[190] This is likely the result of companies capitalizing on the rise of e-cigarette use among young people.[190] E-cigarettes are being used to inhale MDMA, cocaine powder, crack cocaine, synthetic cathinones, mephedrone, α-PVP, synthetic cannabinoids, opioids, heroin, fentanyl, tryptamines, and ketamine.[191]

Looming concerns exist with the potential misuse with liquids containing the active ingredients of cannabis by youth, and with e-cigarette devices that could potentially be used to deliver other psychoactive drugs, including methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, or cathinones.[31] Being exposed to nicotine early on can lead to greater risk of dependence later in life for nicotine and other drugs such as alcohol.[193] Nicotine obtained from vaping is frequently used in combination with alcohol.[194] E-cigarettes users are much more likely to misuse alcohol than non-e-cigarette users.[195] Nicotine and alcohol can have reinforce enhancing effects that may encourage co-use.[196] Vaping increases alcohol drinking among adolescents.[197] Smoking blunt cigars is associated with vaping.[198] The very limited data found that from a small community of 55 users, suggest that cannabis vaping via e-cigarettes or e-vaporizers are infrequent behaviors among cannabis users, and mostly practiced by middle-aged men.[31] A 2015 study found that 5.4% of US middle and high school students were vaping cannabis using e-cigarettes and 18% of vapers had also tried vaping cannabis using their e-cigarette.[199] A 2015 Monitoring the Future survey findings on e-cigarette use highlights uncertainty about what teens are actually inhaling when using vaping devices, and at least 6% report they are using the vaporizers to inhale cannabis.[200] About 6% do not know what substance they last vaped.[200]

Some personal vaporizer devices can be used with cannabis plant material or a concentrated resin form of cannabis called "wax".[89] E-cigarettes can be altered to use hash oil, wax concentrated with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), or dried cannabis leaves.[201] E-liquids may be filled with substances other than nicotine, thus serving as a way to deliver other psychoactive drugs, for example THC.[31] Cannabinoid-enriched e-liquids require lengthy, complex processing, some being readily available online despite lack of quality control, expiry date, conditions of preservation, or any toxicological and clinical assessment.[31] The health effects specific to vaping these cannabis preparations is largely unknown.[31]

Notes

- A 2012 review found "Whereas the "gateway" hypothesis does not specify mechanistic connections between "stages", and does not extend to the risks for addictions, the concept of common liability to addictions incorporates sequencing of drug use initiation as well as extends to related addictions and their severity, provides a parsimonious explanation of substance use and addiction co-occurrence, and establishes a theoretical and empirical foundation to research in etiology, quantitative risk and severity measurement, as well as targeted non-drug-specific prevention and early intervention."[71]

Bibliography

- McNeill, A; Brose, LS; Calder, R; Bauld, L; Robson, D (February 2018). "Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018" (PDF). UK: Public Health England. pp. 1–243.

- National Academies Of Sciences, Engineering; Health Medicine, Division; Board on Population Health Public Health Practice; Committee on the Review of the Health Effects of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems; Eaton, D. L.; Kwan, L. Y.; Stratton, K. (January 2018). Stratton, Kathleen; Kwan, Leslie Y.; Eaton, David L. (eds.). Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes (PDF). National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. National Academies Press. pp. 1–774. doi:10.17226/24952. ISBN 978-0-309-46834-3. PMID 29894118.

- McNeill, A; Brose, LS; Calder, R; Hitchman, SC; Hajek, P; McRobbie, H (August 2015). "E-cigarettes: an evidence update" (PDF). UK: Public Health England. pp. 1–113.

- Wilder, Natalie; Daley, Claire; Sugarman, Jane; Partridge, James (April 2016). "Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction". UK: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 1–191.

- Linda Bauld; Kathryn Angus; Marisa de Andrade (May 2014). "E-cigarette uptake and marketing" (PDF). UK: Public Health England. pp. 1–19.

- "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). World Health Organization. 21 July 2014. pp. 1–13.

References

- Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L. P.; Ribisl, K. M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M. R.; Robertson, R. M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (24 August 2014). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. PMID 25156991.

- Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. Bibcode:2015NYASA1340...65R. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- Jones, Lora (15 September 2019). "Vaping: How popular are e-cigarettes? - Spending on e-cigarettes is growing". BBC News.

- Schraufnagel, Dean E.; Blasi, Francesco; Drummond, M. Bradley; Lam, David C. L.; Latif, Ehsan; Rosen, Mark J.; Sansores, Raul; Van Zyl-Smit, Richard (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes. A Position Statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (6): 611–618. doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 25006874.

- Bourke, Liam; Bauld, Linda; Bullen, Christopher; Cumberbatch, Marcus; Giovannucci, Edward; Islami, Farhad; McRobbie, Hayden; Silverman, Debra T.; Catto, James W.F. (2017). "E-cigarettes and Urologic Health: A Collaborative Review of Toxicology, Epidemiology, and Potential Risks". European Urology. 71 (6): 915–923. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.12.022. hdl:1893/24937. ISSN 0302-2838. PMID 28073600.

- Rahman, Muhammad; Hann, Nicholas; Wilson, Andrew; Worrall-Carter, Linda (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tobacco Induced Diseases. 12 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653. PMID 25745382.

- Cai, Hua; Wang, Chen (2017). "Graphical review: The redox dark side of e-cigarettes; exposure to oxidants and public health concerns". Redox Biology. 13: 402–406. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2017.05.013. ISSN 2213-2317. PMC 5493817. PMID 28667909.

- West, Robert; Beard, Emma; Brown, Jamie (9 January 2018). "Electronic cigarettes in England - latest trends (STS140122)". Smoking in England. p. 28.

- Camenga, Deepa R.; Klein, Jonathan D. (2016). "Tobacco Use Disorders". Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 25 (3): 445–460. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2016.02.003. ISSN 1056-4993. PMC 4920978. PMID 27338966.

- Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes (PDF). The National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine (Report).

- Etter, Jean-François (2018). "Gateway effects and electronic cigarettes". Addiction. 113 (10): 1776–1783. doi:10.1111/add.13924. hdl:2027.42/143795. ISSN 1360-0443. PMID 28786147.

- Schneider, Sven; Diehl, Katharina (2016). "Vaping as a Catalyst for Smoking? An Initial Model on the Initiation of Electronic Cigarette Use and the Transition to Tobacco Smoking Among Adolescents". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 18 (5): 647–653. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv193. ISSN 1462-2203. PMID 26386472.

- Yoong, Sze Lin; Stockings, Emily; Chai, Li Kheng; Tzelepis, Flora; Wiggers, John; Oldmeadow, Christopher; Paul, Christine; Peruga, Armando; Kingsland, Melanie; Attia, John; Wolfenden, Luke (2018). "Prevalence of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use among youth globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis of country level data". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 42 (3): 303–308. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12777. ISSN 1326-0200. PMID 29528527.

- Biyani, Sneh; Derkay, Craig S. (2017). "E-cigarettes: An update on considerations for the otolaryngologist". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 94: 14–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.12.027. ISSN 0165-5876. PMID 28167004.

- McNeill 2015, p. 87.

- Zhong, Jieming; Cao, Shuangshuang; Gong, Weiwei; Fei, Fangrong; Wang, Meng (2016). "Electronic Cigarettes Use and Intention to Cigarette Smoking among Never-Smoking Adolescents and Young Adults: A Meta-Analysis". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (5): 465. doi:10.3390/ijerph13050465. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4881090. PMID 27153077.

- Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- Grana, Rachel; Benowitz, Neal; Glantz, Stanton A. (13 May 2014). "E-Cigarettes". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–1986. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. ISSN 0009-7322. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- Peterson, Lisa A.; Hecht, Stephen S. (2017). "Tobacco, E-Cigarettes and Child Health". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 29 (2): 225–230. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000456. ISSN 1040-8703. PMC 5598780. PMID 28059903.

- Chatterjee, Kshitij; Alzghoul, Bashar; Innabi, Ayoub; Meena, Nikhil (9 August 2016). "Is vaping a gateway to smoking: a review of the longitudinal studies". International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 30 (3). doi:10.1515/ijamh-2016-0033. ISSN 2191-0278. PMID 27505084. S2CID 23977146.

- Pesko, Mike. "Pesko_ECig_Research.pdf". Google Docs.

- Bauld, Linda; MacKintosh, Anne; Eastwood, Brian; Ford, Allison; Moore, Graham; Dockrell, Martin; Arnott, Deborah; Cheeseman, Hazel; McNeill, Ann (29 August 2017). "Young People's Use of E-Cigarettes across the United Kingdom: Findings from Five Surveys 2015–2017". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (9): 973. doi:10.3390/ijerph14090973. PMC 5615510. PMID 28850065.

- "E-cigarette use triples among middle and high school students in just one year". Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Newsroom (2015).

- Levy, David T; Warner, Kenneth E; Cummings, K Michael; Hammond, David; Kuo, Charlene; Fong, Geoffrey T; Thrasher, James F; Goniewicz, Maciej Lukasz; Borland, Ron (November 2019). "Examining the relationship of vaping to smoking initiation among US youth and young adults: a reality check". Tobacco Control. 28 (6): 629–635. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054446. PMC 6860409. PMID 30459182.

- Hallingberg, Britt; Maynard, Olivia M.; Bauld, Linda; Brown, Rachel; Gray, Linsay; Lowthian, Emily; MacKintosh, Anne-Marie; Moore, Laurence; Munafo, Marcus R.; Moore, Graham (1 March 2020). "Have e-cigarettes renormalised or displaced youth smoking? Results of a segmented regression analysis of repeated cross sectional survey data in England, Scotland and Wales". Tobacco Control. 29 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054584. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 7036293. PMID 30936390.

- Pesko, Mike. "Pesko_ECig_Research.pdf". Google Docs.

- Glantz, Stanton A.; Bareham, David W. (January 2018). "E-Cigarettes: Use, Effects on Smoking, Risks, and Policy Implications". Annual Review of Public Health. 39 (1): 215–235. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013757. ISSN 0163-7525. PMC 6251310. PMID 29323609.

This article incorporates text by Stanton A. Glantz and David W. Bareham available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Stanton A. Glantz and David W. Bareham available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Pepper, J. K.; Brewer, N. T. (2013). "Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review". Tobacco Control. 23 (5): 375–384. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 4520227. PMID 24259045.

- Qasim, Hanan; Karim, Zubair A.; Rivera, Jose O.; Khasawneh, Fadi T.; Alshbool, Fatima Z. (2017). "Impact of Electronic Cigarettes on the Cardiovascular System". Journal of the American Heart Association. 6 (9): e006353. doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.006353. ISSN 2047-9980. PMC 5634286. PMID 28855171.

- Weaver, Michael; Breland, Alison; Spindle, Tory; Eissenberg, Thomas (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 8 (4): 234–240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000043. ISSN 1932-0620. PMC 4123220. PMID 25089953.

- Giroud, Christian; de Cesare, Mariangela; Berthet, Aurélie; Varlet, Vincent; Concha-Lozano, Nicolas; Favrat, Bernard (2015). "E-Cigarettes: A Review of New Trends in Cannabis Use". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 12 (8): 9988–10008. doi:10.3390/ijerph120809988. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 4555324. PMID 26308021.

This article incorporates text by Christian Giroud, Mariangela de Cesare, Aurélie Berthet, Vincent Varlet, Nicolas Concha-Lozano, and Bernard Favrat available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Christian Giroud, Mariangela de Cesare, Aurélie Berthet, Vincent Varlet, Nicolas Concha-Lozano, and Bernard Favrat available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Michael Felberbaum (11 June 2013). "Marlboro Maker To Launch New Electronic Cigarette". HuffPost.

- Hartwell, Greg; Thomas, Sian; Egan, Matt; Gilmore, Anna; Petticrew, Mark (2017). "E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups". Tobacco Control. 26 (e2): e85–e91. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 5739861. PMID 28003324.

- Mickle, Tripp (17 November 2015). "E-Cigarette Sales Rapidly Lose Steam". Wall Street Journal.

- McCausland, Kahlia; Maycock, Bruce; Leaver, Tama; Jancey, Jonine (2019). "The Messages Presented in Electronic Cigarette–Related Social Media Promotions and Discussion: Scoping Review". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 21 (2): e11953. doi:10.2196/11953. ISSN 1438-8871. PMC 6379814. PMID 30720440.

This article incorporates text by Kahlia McCausland, Bruce Maycock, Tama Leaver, and Jonine Jancey available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Kahlia McCausland, Bruce Maycock, Tama Leaver, and Jonine Jancey available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Carroll Chapman, SL; Wu, LT (18 Mar 2014). "E-cigarette prevalence and correlates of use among adolescents versus adults: A review and comparison". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 54: 43–54. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.03.005. PMC 4055566. PMID 24680203.

- Alawsi, F.; Nour, R.; Prabhu, S. (2015). "Are e-cigarettes a gateway to smoking or a pathway to quitting?". BDJ. 219 (3): 111–115. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.591. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 26271862. S2CID 24120636.

- McRobbie, Hayden; Bullen, Chris; Hartmann-Boyce, Jamie; Hajek, Peter; McRobbie, Hayden (2014). "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. PMID 25515689.

- Bullen, Christopher (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation". Current Cardiology Reports. 16 (11): 538. doi:10.1007/s11886-014-0538-8. ISSN 1523-3782. PMID 25303892. S2CID 2550483.

- Glasser, Allison M.; Collins, Lauren; Pearson, Jennifer L.; Abudayyeh, Haneen; Niaura, Raymond S.; Abrams, David B.; Villanti, Andrea C. (2017). "Overview of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: A Systematic Review". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 52 (2): e33–e66. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.036. ISSN 0749-3797. PMC 5253272. PMID 27914771.

- DeVito, Elise E.; Krishnan-Sarin, Suchitra (2017). "E-cigarettes: Impact of E-Liquid Components and Device Characteristics on Nicotine Exposure". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (4): 438–459. doi:10.2174/1570159X15666171016164430. ISSN 1570-159X. PMC 6018193. PMID 29046158.

- Couch, Elizabeth T.; Chaffee, Benjamin W.; Gansky, Stuart A.; Walsh, Margaret M. (2016). "The changing tobacco landscape". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 147 (7): 561–569. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2016.01.008. ISSN 0002-8177. PMC 4925234. PMID 26988178.

- Tomashefski, A (21 March 2016). "The perceived effects of electronic cigarettes on health by adult users: A state of the science systematic literature review". Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners. 28 (9): 510–515. doi:10.1002/2327-6924.12358. PMID 26997487. S2CID 42900184.

- Serror, K.; Chaouat, M.; Legrand, Matthieu M.; Depret, F.; Haddad, J.; Malca, N.; Mimoun, M.; Boccara, D. (2018). "Burns caused by electronic vaping devices (e-cigarettes): A new classification proposal based on mechanisms". Burns. 44 (3): 544–548. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2017.09.005. ISSN 0305-4179. PMID 29056367.

- Farsalinos, Konstantinos E.; Spyrou, Alketa; Tsimopoulou, Kalliroi; Stefopoulos, Christos; Romagna, Giorgio; Voudris, Vassilis (2014). "Nicotine absorption from electronic cigarette use: comparison between first and new-generation devices". Scientific Reports. 4: 4133. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4133F. doi:10.1038/srep04133. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3935206. PMID 24569565.

- Vogel, Wendy H. (2016). "E-Cigarettes: Are They as Safe as the Public Thinks?". Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology. 7 (2): 235–240. doi:10.6004/jadpro.2016.7.2.9. ISSN 2150-0878. PMC 5226315. PMID 28090372.

- Cormet-Boyaka, Estelle; Zare, Samane; Nemati, Mehdi; Zheng, Yuqing (2018). "A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: Flavor, nicotine strength, and type". PLOS ONE. 13 (3): e0194145. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1394145Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194145. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5854347. PMID 29543907.

This article incorporates text by Samane Zare, Mehdi Nemati, and Yuqing Zheng available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Samane Zare, Mehdi Nemati, and Yuqing Zheng available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - McNeill 2018, p. 106.

- Ebbert, Jon O.; Agunwamba, Amenah A.; Rutten, Lila J. (2015). "Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 25572196.

- Rinkoo, ArvindVashishta; Kaur, Jagdish (2017). "Getting real with the upcoming challenge of electronic nicotine delivery systems: The way forward for the South-East Asia region". Indian Journal of Public Health. 61 (5): S7–S11. doi:10.4103/ijph.IJPH_240_17. ISSN 0019-557X. PMID 28928312.

- Hartwell, Greg; Thomas, Sian; Egan, Matt; Gilmore, Anna; Petticrew, Mark (2016). "E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups". Tobacco Control. 26: tobaccocontrol–2016–053222. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 28003324.

- Sanford Z, Goebel L (2014). "E-cigarettes: an up to date review and discussion of the controversy". W V Med J. 110 (4): 10–5. PMID 25322582.

- Zborovskaya, Y (2017). "E-Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation: A Primer for Oncology Clinicians". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 21 (1): 54–63. doi:10.1188/17.CJON.54-63. PMID 28107337. S2CID 206992720.

- Lee, Peter N (2015). "Appropriate and inappropriate methods for investigating the "gateway" hypothesis, with a review of the evidence linking prior snus use to later cigarette smoking". Harm Reduction Journal. 12 (1): 8. doi:10.1186/s12954-015-0040-7. ISSN 1477-7517. PMC 4369866. PMID 25889396.

This article incorporates text by Peter N Lee available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Peter N Lee available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Franck, C.; Budlovsky, T.; Windle, S. B.; Filion, K. B.; Eisenberg, M. J. (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes in North America: History, Use, and Implications for Smoking Cessation". Circulation. 129 (19): 1945–1952. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006416. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 24821825.

- Stratton 2018, Conceptual Framework: Patterns of Use Among Youth and Young Adults; p. 497.

- Walker, Natalie; Parag, Varsha; Wong, Sally F.; Youdan, Ben; Broughton, Boyd; Bullen, Christopher; Beaglehole, Robert (1 April 2020). "Use of e-cigarettes and smoked tobacco in youth aged 14–15 years in New Zealand: findings from repeated cross-sectional studies (2014–19)". The Lancet Public Health. 5 (4): e204–e212. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30241-5. ISSN 2468-2667. PMID 31981489.

- Hajek, Peter; Phillips-Waller, Anna; Przulj, Dunja; Pesola, Francesca; Myers Smith, Katie; Bisal, Natalie; Li, Jinshuo; Parrott, Steve; Sasieni, Peter; Dawkins, Lynne; Ross, Louise; Goniewicz, Maciej; Wu, Qi; McRobbie, Hayden J. (14 February 2019). "A Randomized Trial of E-Cigarettes versus Nicotine-Replacement Therapy". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (7): 629–637. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808779. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30699054.

- Jackson, Sarah E.; Kotz, Daniel; West, Robert; Brown, Jamie (2019). "Moderators of real-world effectiveness of smoking cessation aids: a population study". Addiction. 114 (9): 1627–1638. doi:10.1111/add.14656. ISSN 1360-0443. PMC 6684357. PMID 31117151.

- Zhu, Shu-Hong; Zhuang, Yue-Lin; Wong, Shiushing; Cummins, Sharon E.; Tedeschi, Gary J. (26 July 2017). "E-cigarette use and associated changes in population smoking cessation: evidence from US current population surveys". BMJ. 358: j3262. doi:10.1136/bmj.j3262. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 5526046. PMID 28747333.

- "Nicotine science and policy Q & A". The counterfactual. 17 February 2020.

- Commissioner, Office of the (24 March 2020). "Trump Administration Combating Epidemic of Youth E-Cigarette Use with Plan to Clear Market of Unauthorized, Non-Tobacco-Flavored E-Cigarette Products". FDA.

- "Youth Online: High School YRBS - 2017 Results | DASH | CDC". nccd.cdc.gov.

- Wang, Teresa W. (2018). "Tobacco Product Use Among Adults — United States, 2017". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 67 (44): 1225–1232. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6744a2. PMC 6223953. PMID 30408019.

- "Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults — United States, 2011". www.cdc.gov.

- "Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults in the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 November 2019.

- Volkow, Nora (August 2015). "Teens Using E-cigarettes More Likely to Start Smoking Tobacco". National Institute on Drug Abuse.

- Fadus, Matthew C.; Smith, Tracy T.; Squeglia, Lindsay M. (1 August 2019). "The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: Factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 201: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.011. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 7183384. PMID 31200279.

- Franck C, Budlovsky T, Windle SB, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ (13 May 2014). "Electronic Cigarettes in North America". Circulation. 129 (19): 1945–1952. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006416. PMID 24821825.

- Naskar, Subrata; Jakati, Praveen Kumar (2017). ""Vaping:" Emergence of a New Paraphernalia". Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 39 (5): 566–572. doi:10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_142_17. ISSN 0253-7176. PMC 5688881. PMID 29200550.

- Vanyukov, Michael M.; Tarter, Ralph E.; Kirillova, Galina P.; Kirisci, Levent; Reynolds, Maureen D.; Kreek, Mary Jeanne; Conway, Kevin P.; Maher, Brion S.; Iacono, William G.; Bierut, Laura; Neale, Michael C.; Clark, Duncan B.; Ridenour, Ty A. (2012). "Common liability to addiction and "gateway hypothesis": Theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 123: S3–S17. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. ISSN 0376-8716. PMC 3600369. PMID 22261179.

- Wilder 2016, p. 123.

- Stratton 2018, Conceptual Framework: Patterns of Use Among Youth and Young Adults; p. 496.

- Shields, Peter G.; Berman, Micah; Brasky, Theodore M.; Freudenheim, Jo L.; Mathe, Ewy A; McElroy, Joseph; Song, Min-Ae; Wewers, Mark D. (2017). "A Review of Pulmonary Toxicity of Electronic Cigarettes In The Context of Smoking: A Focus On Inflammation". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 26 (8): 1175–1191. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0358. ISSN 1055-9965. PMC 5614602. PMID 28642230.

- Farsalinos, Konstantinos; LeHouezec, Jacques (2015). "Regulation in the face of uncertainty: the evidence on electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes)". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 8: 157–67. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S62116. ISSN 1179-1594. PMC 4598199. PMID 26457058.

- WHO 2014, p. 6.

- Drope, Jeffrey; Cahn, Zachary; Kennedy, Rosemary; Liber, Alex C.; Stoklosa, Michal; Henson, Rosemarie; Douglas, Clifford E.; Drope, Jacqui (2017). "Key issues surrounding the health impacts of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and other sources of nicotine". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 67 (6): 449–471. doi:10.3322/caac.21413. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 28961314.

- Kandel, Denise; Kandel, Eric (2015). "The Gateway Hypothesis of substance abuse: developmental, biological and societal perspectives". Acta Paediatrica. 104 (2): 130–137. doi:10.1111/apa.12851. ISSN 0803-5253. PMID 25377988. S2CID 33575141.

- Hefner, Kathryn; Valentine, Gerald; Sofuoglu, Mehmet (2017). "Electronic cigarettes and mental illness: Reviewing the evidence for help and harm among those with psychiatric and substance use disorders". The American Journal on Addictions. 26 (4): 306–315. doi:10.1111/ajad.12504. ISSN 1055-0496. PMID 28152247. S2CID 24298173.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Dautzenberg, B.; Adler, M.; Garelik, D.; Loubrieu, J.F.; Mathern, G.; Peiffer, G.; Perriot, J.; Rouquet, R.M.; Schmitt, A.; Underner, M.; Urban, T. (2017). "Practical guidelines on e-cigarettes for practitioners and others health professionals. A French 2016 expert's statement". Revue des Maladies Respiratoires. 34 (2): 155–164. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2017.01.001. ISSN 0761-8425. PMID 28189437.

- Nansseu, Jobert Richie N.; Bigna, Jean Joel R. (2016). "Electronic Cigarettes for Curbing the Tobacco-Induced Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases: Evidence Revisited with Emphasis on Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa". Pulmonary Medicine. 2016: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2016/4894352. ISSN 2090-1836. PMC 5220510. PMID 28116156.

This article incorporates text by Jobert Richie N. Nansseu and Jean Joel R. Bigna available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Jobert Richie N. Nansseu and Jean Joel R. Bigna available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Stratton 2018, Conceptual Framework: Patterns of Use Among Youth and Young Adults; p. 531.

- Wilder 2016, p. 128.

- Wilder 2016, pp. 186-187.

- McNeill 2015, p. 38.

- Ferkol, Thomas W.; Farber, Harold J.; Grutta, Stefania La; Leone, Frank T.; Marshall, Henry M.; Neptune, Enid; Pisinger, Charlotta; Vanker, Aneesa; Wisotzky, Myra; Zabert, Gustavo E.; Schraufnagel, Dean E. (1 May 2018). "Electronic cigarette use in youths: a position statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies". European Respiratory Journal. 51 (5): 1800278. doi:10.1183/13993003.00278-2018. ISSN 0903-1936. PMID 29848575.

- Suter, Melissa A.; Mastrobattista, Joan; Sachs, Maike; Aagaard, Kjersti (2015). "Is There Evidence for Potential Harm of Electronic Cigarette Use in Pregnancy?". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 103 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1002/bdra.23333. ISSN 1542-0752. PMC 4830434. PMID 25366492.

- England, Lucinda J.; Bunnell, Rebecca E.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Tong, Van T.; McAfee, Tim A. (2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49 (2): 286–93. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. ISSN 0749-3797. PMC 4594223. PMID 25794473.

- "E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General" (PDF). Surgeon General of the United States. 2016. pp. 1–298.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Kapaya, Martha (2019). "Use of Electronic Vapor Products Before, During, and After Pregnancy Among Women with a Recent Live Birth — Oklahoma and Texas, 2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 (8): 189–194. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6808a1. PMC 6394383. PMID 30817748.

- Liu, Buyun; Xu, Guifeng; Rong, Shuang; Santillan, Donna A.; Santillan, Mark K.; Snetselaar, Linda G.; Bao, Wei (2019). "National Estimates of e-Cigarette Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Women of Reproductive Age in the United States, 2014-2017". JAMA Pediatrics. 173 (6): 600–602. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0658. ISSN 2168-6211. PMC 6547070. PMID 31034001.

- Pesko, Michael F.; Currie, Janet M. (1 July 2019). "E-cigarette minimum legal sale age laws and traditional cigarette use among rural pregnant teenagers". Journal of Health Economics. 66: 71–90. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.05.003. ISSN 0167-6296. PMC 7051858. PMID 31121389.

- Breland, Alison; Soule, Eric; Lopez, Alexa; Ramôa, Carolina; El-Hellani, Ahmad; Eissenberg, Thomas (2017). "Electronic cigarettes: what are they and what do they do?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1394 (1): 5–30. Bibcode:2017NYASA1394....5B. doi:10.1111/nyas.12977. ISSN 0077-8923. PMC 4947026. PMID 26774031.

- Zainol Abidin, Najihah; Zainal Abidin, Emilia; Zulkifli, Aziemah; Karuppiah, Karmegam; Syed Ismail, Sharifah Norkhadijah; Amer Nordin, Amer Siddiq (2017). "Electronic cigarettes and indoor air quality: a review of studies using human volunteers" (PDF). Reviews on Environmental Health. 0 (3): 235–244. doi:10.1515/reveh-2016-0059. ISSN 2191-0308. PMID 28107173. S2CID 6885414.

- McNeill 2018, p. 99.

- McNeill 2018, p. 100.

- Jenssen, Brian P.; Walley, Susan C. (2019). "E-Cigarettes and Similar Devices". Pediatrics. 143 (2): e20183652. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3652. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 6644065. PMID 30835247.

- "Electronic Cigarettes". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 September 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Charlotte A. Schoenborn; Renee M. Gindi (October 2015). "Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults: United States, 2014" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. pp. 1–8.

- Syamlal, Girija; Jamal, Ahmed; King, Brian A.; Mazurek, Jacek M. (2016). "Electronic Cigarette Use Among Working Adults — United States, 2014". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (22): 557–561. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6522a1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 27281058.

- Mincer, Jilian (10 June 2015). "E-cigarette usage surges in past year: Reuters/Ipsos poll". Reuters.

- Delnevo, Cristine D.; Giovenco, Daniel P.; Steinberg, Michael B.; Villanti, Andrea C.; Pearson, Jennifer L.; Niaura, Raymond S.; Abrams, David B. (2 November 2015). "Patterns of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Adults in the United States". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 18 (5): 715–719. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntv237. PMC 5896829. PMID 26525063.

- Pesko, Michael; Warman, Casey (5 September 2017). "The Effect of Prices and Taxes on Youth Cigarette and E-cigarette Use: Economic Substitutes or Complements?". Social Science Research Network. SSRN 3077468. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Saffer, Henry; Dench, Daniel L; Grossman, Michael; Dave, Dhaval M (December 2019). "E-Cigarettes and Adult Smoking: Evidence from Minnesota". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26589. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Pesko, Michael F; Courtemanche, Charles J; Maclean, Johanna Catherine (June 2019). "The Effects of Traditional Cigarette and E-Cigarette Taxes on Adult Tobacco Product Use". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Abouk, Rahi; Adams, Scott; Feng, Bo; Maclean, Johanna Catherine; Pesko, Michael F (July 2019). "The Effect of E-Cigarette Taxes on Pre-Pregnancy and Prenatal Smoking, and Birth Outcomes". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26126. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cotti, Chad D; Courtemanche, Charles J; Maclean, Johanna Catherine; Nesson, Erik T; Pesko, Michael F; Tefft, Nathan (January 2020). "The Effects of E-Cigarette Taxes on E-Cigarette Prices and Tobacco Product Sales: Evidence from Retail Panel Data". National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w26724. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Das, Smita; Prochaska, Judith J. (2017). "Innovative approaches to support smoking cessation for individuals with mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 11 (10): 841–850. doi:10.1080/17476348.2017.1361823. ISSN 1747-6348. PMC 5790168. PMID 28756728.

- Lauterstein, Dana; Hoshino, Risa; Gordon, Terry; Watkins, Beverly-Xaviera; Weitzman, Michael; Zelikoff, Judith (2014). "The Changing Face of Tobacco Use Among United States Youth". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (1): 29–43. doi:10.2174/1874473707666141015220110. ISSN 1874-4737. PMC 4469045. PMID 25323124.

- Singh, Tushar; Kennedy, Sara; Marynak, Kristy; Persoskie, Alexander; Melstrom, Paul; King, Brian A. (2016). "Characteristics of Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students — United States, 2015". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (5051): 1425–1429. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051a2. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 28033310.