Victor Electrics

Victor Electrics Ltd was a British manufacturer of milk floats and other battery electric road vehicles. The company was formed in 1923 by Outram's Bakery in Southport, Merseyside, to make bread vans for their own use, but they soon diversified into other markets, including the Dairy industry. Their first vehicles had bonnets, like conventional vans, which stored the batteries, but by 1935 all of their vehicles were forward control models, with the cab at the front. They were acquired by Brook Motors in 1967, and became part of the Hawker Siddeley group in 1970. They made a small number of railway locomotives during this latter period.

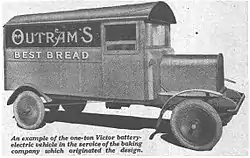

One of the first bread vans built for Outram's Bakery by Victor Electrics. The picture dates from 1927. | |

| Industry | Battery Electric Vehicles |

|---|---|

| Successor | Brook Motors; Hawker Siddeley |

| Founded | 1923 |

| Defunct | 1970s |

| Headquarters | Southport, England |

| Products | Milk float |

| Footnotes / references Many vehicles produced by Victor Electrics were classified by their payload, which was measured in hundredweights, and this usage has been retained in the article. A hundredweight is one twentieth of a long ton or 51kg, and is abbreviated to "cwt".

| |

History

Outram's was a large bakery based in Southport, Merseyside, England. In the early 1920s they ran a fleet of steam lorries, petrol vans and horses and carts, which were used to deliver bakery products both nationwide and locally. They wanted to buy some electric vehicles to replace some of the horses, but found that both home-produced and imported vehicles were considerably more expensive than they were prepared to pay. They were looking for something that was comparable in price to their Ford vans, and so formed Victor Electrics Ltd., appointing one of their directors, H N Outram, as its joint managing director. Their first electric van was finished in 1923, and they built several more. They proved to be successful, and in 1927, they investigated the possibility of allowing another company, already involved in the manufacture of electric road vehicles, to take over the enterprise. Victor Electrics was initially located on Lord Street, Southport.[1]

The vehicles sold for £150, which included the battery, and were slightly larger than the Ford 1-ton vans which the bakery also ran. They could carry 800 tin loaves. The vehicles looked like a conventional van, with the batteries placed under a bonnet at the front. The chassis was constructed of wood, strengthened with some steel channel, and Ford components were used for the steering gear and rear axle, although the final gearing was modified to give a lower ratio. The motor was mounted in the centre of the vehicle, and drove the rear axle through a propellor shaft and overhead worm drive. Power at 48 volts was provided by a 24-cell battery supplied by D P Kathanode, rated at 143 Amp-hours. Control was through a 4-stage series-parallel controller with starting resistances, and some electric braking was provided by using the resistances. The weight of the vehicle was around 17 cwt, with the battery weighing an additional 5 to 6 cwt.[1]

By 1929, Victor were making three models of bonnetted van, all with similar basic dimensions, but differing in the length of the rear storage area. They were 5 feet 4 inches (1.63 m) wide, with a wheelbase of 10 feet (3.0 m). The Model A was designed for a 20 cwt payload, and formed the basis for a number of vans supplied to the General Post Office in 1929. It came with a 3 hp (2.2 kW) motor running at 48 volts. The Model B had a larger 4.75 hp (3.54 kW) motor running at 40 volts, and was supplied with a 192 Amp-hour battery as standard, but extra batteries could be fitted at the rear of the vehicle, which carried 23 cwt. The Model C was the largest, with a 6 hp (4.5 kW) motor running at 80 volts. The batteries under the bonnet were supplemented by others which were either mounted under the driver's seat, or at the rear. The payload was 30 cwt.[2]

In 1931 they introduced a 27 cwt vehicle designed for the Dairy industry, with forward control and a walk-through cab having no doors. The 40-cell, 168 Ahr battery, manufactured by D P Kathanode, was located over the front axle, and supplied current to a Metro-Vick motor. The vehicle was designed to be driven while standing up, with the controls only enabled when the driver was standing on a spring-loaded floor button. The controls were also interlocked with the hand brake.[3]

Victor switched to forward control models, rather than bonneted models in 1935, with the introduction of the B10, available for 15 cwt, 10 cwt or 6 cwt payloads, the B20, for 25 cwt, 20 cwt or 15 cwt payloads, and the B30, for 40 cwt, 30 cwt or 20 cwt payloads. In each range, the lower payloads gave a corresponding increase in the top speed and range. By this time, the company had moved to Burscough Bridge, Ormskirk.[4]

Victor extended their range of a 25 cwt and a 2-ton vehicle by the addition of a 12 cwt model in 1936. All of their vehicles were designed to have a top speed of 20 mph. The electric motor was mounted just behind the front wheels, and drove the rear wheels through a propellor shaft and bevel rear axle. The front wheels were fitted with independent suspension, to reduce pitching, and the buyer could specify whether they wanted steering to be by a tiller or a wheel.[5]

In 1945 Victor announced that it had developed a battery-electric vehicle which did not need a separate charger, but could be plugged into any standard heater plug. This principle had been tried to good effect in Europe. Other innovations included the concept of a standard battery, which could be fitted to eight different vehicles with payloads ranging from 10 cwt to 80 cwt. A single battery would be fitted to the smallest vehicle, and four to the largest. They also announced a scheme by which batteries could be hired, rather than bought outright.[6]

Acquisition

Victor Electrics set up a company called Ross Auto Engineering in 1949, who were also based in Southport,[7] and who produced battery electric road vehicles in their own right. However, Victor carried on producing their own models as well.

In 1967, the company was acquired by Brook Motors, who had been manufacturing electric motors since 1904. The joint enterprise was known as Brook Victor Electric Vehicles. It had a full order book in 1968 and won the Queen's Award to Industry on the strength of its export performance. Brook Victor was itself acquired by Hawker Siddeley in 1970, and in 1973 it became Brook Crompton Parkinson Motors.[8]

In 1973, the company, by then named Brook Victor Electric Vehicles, introduced a 3-ton platform truck, which came with pneumatic types, but an option for solid tyres was available.[9] They also produced a small number of battery-electric locomotives for the 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauge Royal Ordnance Factory railway at Bishopton, Renfrewshire, four of which are preserved on the Almond Valley Light Railway,[10] and one at the Moseley Railway.[11]

Preservation

There is only one Victor milk float known to still exist. It is a B20 model dating from around 1955, and is currently awaiting restoration at The Transport Museum, Wythall, to the south of Birmingham.[12]

Bibliography

- Ward, Rod (2008). Electric Vehicles. Auto Review. Zeteo Publishing. ISBN 978-1-900482-41-7.

References

- "An Electric Designed by a Baker". Commercial Motor. 1 February 1927. p. 46.

- "An Electric Van". Commercial Motor. 17 September 1929. p. 67.

- "Door to Door Delivery by Electric Van". Commercial Motor. 13 January 1931. p. 53.

- "Victor Electrics for 1935". Commercial Motor. 9 November 1934. p. 72.

- "The Victor Electric 1936 Range". Commercial Motor. 11 October 1935. p. 55.

- "New Battery Scheme for Electric Vehicles". Commercial Motor. 21 September 1945. p. 23.

- Ward 2008, p. 26.

- "Brook Motors". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- "Platform Truck". Commercial Motor. 7 September 1973. p. 95.

- "Light Railway Vehicle Stockbook" (PDF). Almond Valley Light Railway. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- "12 "Electra"". Moseley Railway Trust. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- "Our Battery Electric Collection". Wythall Transport Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2016.