Vilna offensive

The Vilna offensive was a campaign of the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1921. The Polish army launched an offensive on April 16, 1919, to take Vilnius (Polish: Wilno) from the Red Army. After three days of street fighting from April 19–21,[4] the city was captured by Polish forces, causing the Red Army to retreat. During the offensive, the Poles also succeeded in securing the nearby cities of Lida, Pinsk, Navahrudak, and Baranovichi.

| Vilna Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Polish–Soviet War[a] | |||||||

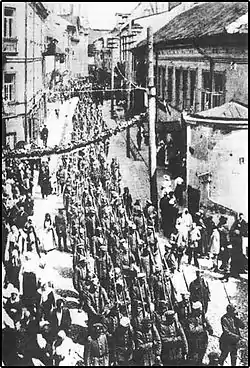

Polish Army enters Vilnius (Wilno), 1919. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Józef Piłsudski W. Belina-Prażmowski Edward Rydz-Śmigły | Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

For the offensive:[1] 10,000 infantry 1,000 cavalry 16 guns For Vilnius:[1] 9 cavalry squadrons 3 infantry battalions artillery support local population Polish 1st Legions Infantry Division had 2,500 soldiers Polish cavalry of colonel Belina had 800 soldiers[2] |

For the offensive:[1] Western Rifle Division and other units of Western Army. 12,000 infantry 3,000 cavalry 44 artillery pieces. For Vilnius:[1] 2,000 soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 33 soldiers[3] | Unknown. Polish military communiques note "more than 1,000 prisoners" taken.[4] | ||||||

The Red Army launched a series of counterattacks in late April, all of which ended in failure. The Soviets briefly recaptured the city a year later, in spring 1920, when the Polish army was retreating along the entire front. In the aftermath, the Vilna offensive would cause much turmoil on the political scene in Poland and abroad.

Prelude

Soviet Russia, while at the time publicly supporting Polish and Lithuanian independence, sponsored communist agitators working against the government of the Second Polish Republic, and considered that the Polish eastern borders should approximate those of the defunct Congress Poland.

Throughout the 19th century, Poles saw the boundaries of their territories as lying much farther east and sought to reestablish the 1772 borders of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. However, by 1919, this concept of Polish borders was already considered unrealistic and was used by Polish politicians merely for tactical purposes during the Versailles Conference.[5] Józef Piłsudski envisioned a revived Commonwealth in the form of a multinational federation consisting of Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and perhaps Latvia[6][7][8] – a plan which was in direct conflict with the Lithuanian wishes of creating the independent Republic of Lithuania. Piłsudski discerned an opportunity for regaining territories that were once the part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and now belonged to the Russian Empire, which was shaken by the 1917 Revolution, the ongoing Russian Civil War,[b] and the Central Powers' offensive.

In the first weeks of 1919, following the retreat of the German Ober-Ost forces under Max Hoffmann, Vilnius found itself in a power vacuum. It promptly became the scene of struggles among competing political groups and experienced several internal revolutions.[9]

On January 1, Polish officers, led by generals Władysław Wejtko and Stefan Mokrzecki, attempted to take control of the city by establishing a Samoobrona ("Self-Defense") provisional government. Their aim was to defeat the Communist "Workers' Council", a rival faction within Vilnius plotting to seize the city.[10] Samoobrona rule of Vilnius did not last long. Four days later January 5, 1919, the Polish forces were forced to make a hasty retreat when the Russian Western Army marched in from Smolensk to support the local communists as part of the Soviet westward offensive.[9]

Vilnius, the historical capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, became part of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic and was soon proclaimed capital of the Lithuanian–Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lit-Bel) on February 27, 1919. The Lit-Bel became the 8th government to control Vilnius in two years.[11] During the month and a half that the Lit-Bel controlled the city, the new communist government turned Vilnius into a social experiment, testing various applications of left-leaning governmental systems on the city's inhabitants.[12][13]

Józef Piłsudski, Polish commander-in-chief,[14] determined that regaining control of Vilnius, whose population consisted mostly of Poles and Jews,[c] should be a priority of the renascent Polish state.[15] He had been working on plans to take control of Vilnius since at least March; he gave preliminary orders to prepare a push in that direction—and counter an expected Soviet westward push—on March 26.[1] One of Piłsudski's objectives was to take control of Vilnius before Western diplomats at the Paris Peace Conference could rule on whom the city, demanded by various factions, should be given to.[16] The action was not discussed with Polish politicians or the government,[16] who at that time were more concerned with the situation on the southern Polish–Ukrainian front.[17] By early April, when members of the Kresy Defence Committee (Komitet Obrony Kresów) Michał Pius Römer, Aleksander Prystor, Witold Abramowicz, and Kazimierz Świtalski met with Pilsudski, stressing the plight of occupied Vilnius and its inhabitants' need for self-government, Piłsudski was ready to move.[18]

Offensive

Diversionary attacks

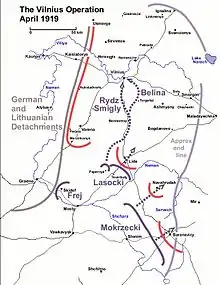

Piłsudski arrived at the front near Lida on 15 April, bringing reinforcements from Warsaw. His plan called for exploitation of the gap in the Soviet lines between Vilnius and Lida by an advance towards Vilnius using the road and railway. Amidst diversionary attacks, designed to draw Russian attention away from the main Polish thrust towards Vilnius, the main Polish attack began at dawn on 16 April.[2] The forces moving on Vilnius included the cavalry group of Colonel Wladyslaw Belina-Prazmowski, composed of 800 men in nine cavalry squadrons and a battery of horse artillery; and infantry under General Edward Rydz-Śmigły, composed of 2,500 men in three battalions of the Polish 1st Legions Infantry Division and two batteries of heavy artillery.[2]

Soviet forces in the area were composed of the Western Rifle Division, a unit which had many pro-communist Polish volunteers,[19] and other units of the Western Army. The Soviet garrison of Vilnius numbered about 2,000 newly trained troops. Soviet forces in the area around Vilnius are estimated at 7,000 infantry, a few hundred cavalry, and 10 artillery pieces.[1] These forces were to be engaged and thus prevented from coming to the aid of the Vilnius garrison.

The diversionary attacks went well, with Soviet forces acting under the impression that the Poles had targets other than Vilnius. Despite their diversionary intent, these attacks succeeded in their own right, with Generał Józef Adam Lasocki taking Lida in two days despite unexpectedly strong resistance,[17] and Generał Stefan Mokrzecki taking Nowogrodek in three days and Baranowicze in four.[2]

Assault on Vilnius

On 18 April, Colonel Belina decided to use the element of surprise and move into Vilnius without waiting for the slower infantry units.[20] Polish forces left the village of Mýto in early morning.[1] At 03:30 on 19 April, Maj. Zaruski took Lipówka near Vilnius.[1] Belina's cavalry bypassed Vilnius and attacked from behind, taking the train station on the night of 18 to 19 April;[21] on 19 April, cavalry under lieutenant Gustaw Orlicz-Dreszer—future Polish general—charged into the suburbs, spreading panic among the confused garrison. He seized the train station and sent a train down the line to collect infantry.[17][20] In this surprise raid about 400 prisoners, 13 trains, and various military supplies were captured.[1] Piłsudski would declare Belina's cavalry action the "most exquisite military action carried out by Polish cavalry in this war".[1]

Cavalrymen fought for control of the center of Vilnius and took Cathedral Square,[21] the castle complex on the hillside, and the enemy quarters on the southern riverbank. They also captured hundreds of Bolshevik soldiers and officials,[1] but their numbers were too small compared to the enemy forces, who had begun to reorganize, particularly in the north and west of the town, and to prepare a counterattack.[17] Belina sent a message reporting that "enemy is resisting with extreme strength"[4] and asking for immediate reinforcements.[21] At around 8:00 in the evening the train he had sent in the morning returned with the first infantry reinforcements. The Polish troops were also supported by the city's predominantly Polish population which formed a militia to aid them.[17] By the evening of 19 April half of Vilnius was under Polish control,[20] however, the Red Army troops and supporters were putting up a stubborn and coordinated defence.[17] Only upon the arrival of the main force of Polish infantry under Generał Śmigły on 21 April did the Poles gain the upper hand, attacking those parts of the town still held by the Red Army.[17] The Polish infantry was able to reinforce the cavalry in the city center, and during the night, with help of local guides, Polish forces crossed the river and took one of the bridges.[1] On April 20, the bridges were in the hands of the Poles, and more of the city fell under their control.[1] During the afternoon of that day, after a three-day-long urban battle, the city was in Polish hands.[20] Piłsudski arrived in Vilnius on the same day.[20]

Jewish deaths

As the Polish troops entered the city, the first pogrom in modern Vilnius started, as noted by the Timothy D. Snyder, citing Michał Pius Römer.[22] Dozens of people connected with the Lit-Bel were arrested, and some were executed; Norman Davies cites a death toll for all – Jews and non-Jews, under Polish rule – as 65.[23] Jews constituted close to one-half of Vilnius's population, according to the German census of 1916,[24] and many victims of fighting and subsequent repression in Vilnius were Jews. Henry Morgenthau, Sr. counted 65,[3] Joseph W. Bendersky counted over a hundred.[25]

There was a common belief among the Poles that most Jews were Bolsheviks and Communists, in league with the enemy of the Polish state, Soviet Russia.[26] The Polish army stated that any Jews it killed were militants and collaborators engaged in actions against the Polish army.[25][27][28] Having been fired at from Jewish homes, Polish soldiers took this as an excuse to break into many Jewish homes and stores, beating the Jews and robbing them, desecrating synagogues, arresting hundreds, depriving them of food and drink for days and deporting them from the city;[25] such abuses were, however, not supported – and even specifically forbidden – by the Polish high command.[3][25][28]

The US Army representative on the scene, Colonel Wiliam F. Godson, agreed with the version of events presented by the Polish general staff.[25] In his reports, Godson wrote that "Jews constituted at least 80% of every Bolshevik organization" and that, unlike the "harmless Polish Jews" (who really "had become Poles"), the "Litwaks or Russian Jews" are "extremely dangerous", making the "Jewish question the most important one [for the country]".[25] Neglecting the plight of the Jews,[25] Godson had only noted in his report the instances of Bolsheviks executing and mutilating civilians and Polish prisoners of war.[25] The Nobel Prize-winning author Władysław Reymont, in an article published by Gazeta Warszawska, the main organ of the openly antisemitic National Democratic Party,[29] also denied that pogroms had taken place.[28] Henry Morgenthau, Sr. of the Anglo-American Investigating Commission in his report acquitted the Polish side of having organized pogroms, noting the wartime confusion and the fact that some Jews had indeed shot at the Polish forces.[28] The report was, however, highly critical of the activities of the Polish Army in Vilnius, noting that 65 Jews with no proven connections to the Bolsheviks had been killed, and that many arrests, robberies and mistreatments had occurred, while soldiers guilty of these acts had not been punished.[3]

Soviet counteroffensive

The Polish victory infuriated the Soviets, leading to dozens of arrests and several executions among those connected to the Lit-Bel.[23] The former Lit-Bel leaders began accusing one another of culpability for the loss of their capital. Lenin considered the city vital to his plans, and ordered its immediate recapture, with the Red Army attempting several counteroffensives in April 1919.[30]

Near the end of the month about 12,000 infantry, 3,000 cavalry, 210 heavy machine guns and 44 guns were assembled by Soviet forces in the area of Szyrwiany, Podbrodzie, Soly and Ashmyany. Polish forces in the area under general Stanisław Szeptycki numbered 11,000; Rydz-Śmigly had 8 infantry battalions, 18 cavalry squadrons and 18 guns in Vilnius itself.[1] Rydz-Śmigły decided to engage the enemy forces before they combined their strengths. On the night of April 28–29, general Stefan Dąb-Biernacki took Podbrodzie, capturing one of the Soviet formations. Simultaneously, Soviet forces attacked near Deliny–Ogrodniki, south of Vilnius. Polish defenses and counterattacks managed to halt Soviet movements towards Vilnius, pushing them back towards Szkodziszki–Grygajce. In retaliation, Soviet forces launched yet another counterattack, this one from north of Vilnius. The results were significantly better than those of the previous offensive, with Soviet forces breaking through Polish defenses in the area. However, Red Army forces halted their movements short of Vilnius, not wishing to attack a hostile city during the night.[31] Polish forces took advantage of the opportunity to strengthen their defenses. Shortly afterwards, Polish forces counterattacked, pushing the Red Army back towards Mejszagoła and Podberezie. Polish forces pursued and took those two settlements, as well as Giedrojsc and Smorgoń. By mid-May Polish forces had reached the line of Narocz lake – Hoduciszki – Ignalina – Lyngniany, leaving Vilnius well behind the frontline.[1]

Aftermath

Because of the successful surprise attack, the Polish army in Vilnius managed to appropriate sizable stocks of supplies and take hundreds of prisoners.[4] When Piłsudski entered the city, a victory parade was held in his honour. The city's Polish citizens on the whole were delighted; their politicians envisaged a separate Lithuanian state closely allied with Poland.[32] Representatives from the city were immediately sent to the Paris Peace Conference, and the Stefan Batory University in Vilnius, which had been closed in 1832 following the November 1830 Uprising, was reopened.[32]

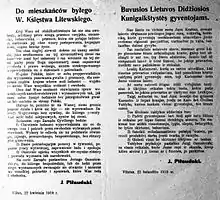

Acting in accordance with his vision of a Polish-led "Międzymorze" federation of East-Central European states, Piłsudski on April 22, 1919, issued a bilingual statement, in Polish and Lithuanian, of his political intentions – the "Proclamation to the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania", pledging to provide "elections [which will] take place on the basis of secret, universal and direct voting, without distinction between the sexes" and to "create an opportunity for settling your nationality problems and religious affairs in a manner that you yourself will determine, without any kind of force or pressure from Poland."[33] Piłsudski's proclamation was aimed at showing good will both to Lithuanians and international diplomats; the latter succeeded as the proclamation dealt a blow to the image of 'Polish conquest' and replaced it with the image of 'Poland fighting with Bolsheviks dictatorship and liberating other nations'; however the Lithuanians who demanded exclusive control over the city were much less convinced.[34] Piłsudski's words also caused significant controversy on the Polish political scene; as they had not been discussed with the Sejm and caused much anger among Piłsudski's National-Democratic opponents; Polish People's Party "Piast" deputies demanded incorporation of the Vilnius Region into Poland and even accused Piłsudski of treason. However, Piłsudski's supporters in the Polish Socialist Party managed to deflect those attacks.[34]

The Lithuanian government in Kaunas, which viewed the city as the historic capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, saw the Polish incursion as an occupation. The Lithuanian government demanded Vilnius back. Relations between the Polish and Lithuanian governments, unable to reach a compromise over Vilnius, continued to worsen, destroying the prospects for Piłsudski's plan of the Międzymorze federation and leading to open hostilities in the ensuing Polish–Lithuanian War.[35] In 1920, the Soviets recaptured Vilnius, followed by the Poles' establishment of the short-lived Republic of Central Lithuania.[36]

The Polish capture of Vilnius set the stage for further escalation of Polish conflicts with Soviet Russia and Lithuania. In coming months, Polish forces would push steadily eastward, launching Operation Minsk in August.[37]

See also

Notes

a ^ For controversies about the naming and dating of this conflict, refer to the section devoted to this subject in the Polish-Soviet War article.

b ^ Speaking of Poland's frontiers Piłsudski said: "All that we can gain in the west depends on the Entente – on the extent to which it may wish to squeeze Germany", while in the east "there are doors that open and close, and it depends on who forces them open and how far."[38]

c ^ Jews of Vilnius had their own complex identity, and labels of Polish Jews, Lithuanian Jews or Russian Jews are all applicable only in part.[39]

References

- Janusz Odziemkowski, Leksykon Wojny Polsko-Rosyjskiej 1919–1920' (Lexicon of Polish–Russian War of 1919–1920), Oficyna Wydawnica RYTM, 2004, ISBN 83-7399-096-8.

- Davies (2003), p. 49

- Mission of The United States to Poland, Henry Morgenthau, Sr. Report

- Collection of Polish military comminiques, 1919–1921, "O niepodległą i granice", Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna, Pułtusk, 1999. pp. 168–172.Part available online in this letter to Rzeczpospolita.

- Eberhardt, Piotr (2012). "The Curzon line as the eastern boundary of Poland. The origins and the political background" (PDF). Geographia Polonica. 85 (1): 6, 8. doi:10.7163/GPol.2012.1.1.

- Trencsényi, Balázs; et al. (2018). A History of Modern Political Thought in East Central Europe: Volume II: Negotiating Modernity in the 'Short Twentieth Century' and Beyond, Part I: 1918-1968. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780198737155.

- Roszkowski, Wojciech; Kofman, Jan (2008). Biographical Dictionary of Central and Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 2253. ISBN 978-0765610270.

- Biskupski, M. B. B.; Pula, James S.; Wróbel, Piotr J., eds. (2010). The Origins of Modern Polish Democracy. Ohio University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0821418925.

- Davies (2003), pp. 25–26

- Davies (2003), p. 25

- Davies (2003), p. 48

- Davies (2003), pp. 48–49

- Poland rebirth in XX century

- MacMillan, Margaret, Paris 1919 : Six Months That Changed the World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2003, ISBN 0-375-76052-0, pp. 213–214.

- Davies (2003), pp. 48, 53–54

- Antoni Czubiński, Walka o granice wschodnie polski w latach 1918–1921 Instytut Slaski w Opolu, 1993 p.83

- Adam Przybylski, 1928, Poland in the Fight for its Borders, April – July 1919 – this chapter contains an account of the battle, mostly identical with the one presented by Davies.

- Grzegorz Lukowski, Rafal E. Stolarski, Walka o Wilno, Oficyna Wydawnicza Audiutor, 1994, ISBN 83-900085-0-5.

- (in Polish) Zachodnia Dywizja Strzelców. WIEM Encyklopedia. Last accessed on 9 April 2007.

- Davies (2003), p. 50

- (in Polish) Bohdan Urbankowski, Józef Piłsudski: marzyciel i strateg (Józef Piłsudski: Dreamer and Strategist), Wydawnictwo ALFA, Warsaw, 1997, ISBN 83-7001-914-5, p. 296.

- Snyder, Timothy (2003). Reconstruction of Nations : Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. p. 49. ISBN 0-300-09569-4.

Jews had been generally sympathetic to the Lithuanian claim, believing that a large multinational Lithuania with Vilne as its capital would be more likely to respect their rights. Their reward in 1919 had been the first pogroms in modern Vilne.

- Davies (2003, p. 240) cites a death toll of 65 under Polish rule, and 2,000 under the brief 1920 Soviet reoccupation)

- Piotr Łossowski, Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918–1920, Książka i Wiedza, 1995, ISBN 83-05-12769-9, p. 11

- Joseph W. Bendersky, The "Jewish Threat": Anti-semitic Politics of the American Arm, Basic Books, 2000, ISBN 0-465-00618-3, Google Print, p.84-86

- Michlic, Joanna Beata (2006). Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 0-8032-3240-3.

- Norman Davies, God's Playground: A History of Poland, Columbia University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-231-12819-3, Google Print, p.192

- Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1997). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide... McFarland & Company. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- Words to Outlive Us: Voices from the Warsaw Ghetto. Michał Grynberg, 2002.

- Gintautas Ereminas, Ochrona toru Wilno – Lida

- (in Italian)Robert Gerwarth, La rabbia dei vinti: La guerra dopo la guerra 1917-1923, Gius.Laterza & Figli Spa (traduzione di David Scaffei), ISBN 978-88-58-13080-3.

- Davies (2003), pp. 53–54

- Davies (2003), p. 51

- Czubiński, p. 92

- Davies (2003), p. 57

- George J. Lerski. Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. 1996, p. 309.

- Davies (2003), pp. 51–53

- Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919 : Six Months That Changed the World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2003, ISBN 0-375-76052-0, p. 212.

- Ezra Mendelsohn, On Modern Jewish Politics, Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 0-19-508319-9, Google Print, p. 8 and Mark Abley, Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages, Houghton Mifflin Books, 2003, ISBN 0-618-23649-X, Google Print, p. 205

Further reading

- Davies, Norman (2003) [1972]. White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20. First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

- Davies, Norman (2001) [1984]. Heart of Europe The Past in Poland's Present. Second edition: 1986. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280126-0.

- Przemysław Różański, "Wilno, 19-21 kwietnia 1919 roku" (Vilna, April 19–21, 1919), Jewish History Quarterly (01/2006), C.E.E.O.L.

- Мельтюхов, Михаил Иванович (Mikhail Meltyukhov) (2001). Советско-польские войны. Военно-политическое противостояние 1918—1939 гг. (Soviet-Polish Wars. Political and Military standoff of 1918–1939) (in Russian). Moscow: Вече (Veche). ISBN 5-699-07637-9. LCCN 2002323889.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1985). Po tej i tamtej stronie Niemna. Stosunki polsko-litewskie 1883–1939 (in Polish). Warszawa: Czytelnik. ISBN 83-07-01289-9.