Violin Concerto (Sibelius)

The Violin Concerto in D minor, Op. 47, was written by Jean Sibelius in 1904, revised in 1905. It is his only concerto. It is symphonic in scope, with the solo violin and all sections of the orchestra being equal voices. An extended cadenza for the soloist takes on the role of the development section in the first movement.

| Violin Concerto | |

|---|---|

| by Jean Sibelius | |

The composer in 1904, by Albert Edelfelt | |

| Key | D minor |

| Catalogue | Op. 47 |

| Period | Late Romantic/Early Modern |

| Genre | Concerto |

| Composed | 1904 (r. 1905) |

| Movements | 3 |

| Scoring | Violin and orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 8 February 1904 |

| Location | Helsinki |

| Conductor | Jean Sibelius |

| Performers |

|

History

Sibelius originally dedicated the concerto to the noted violinist Willy Burmester, who promised to play the concerto in Berlin. For financial reasons, however, Sibelius decided to premiere it in Helsinki, and since Burmester was unavailable to travel to Finland, Sibelius engaged Victor Nováček (1873–1914),[1] a Hungarian violin pedagogue of Czech origin who was then teaching at the Helsinki Institute of Music (now the Sibelius Academy).

The initial version of the concerto premiered on 8 February 1904, with Sibelius conducting. Sibelius had barely finished the work in time for the premiere, giving Nováček little time to prepare, and the piece was of such difficulty that it would have sorely tested even a player of much greater skill. Given these factors, it was unwise of Sibelius to choose Nováček, who was a teacher and not a recognised soloist, and it is not surprising that the premiere was a disaster.[2] However, Nováček was not the poor player he is sometimes painted as. He was the first violinist hired by Martin Wegelius for the Helsinki Institute, and in 1910 he participated in the premiere of Sibelius's string quartet Voces intimae, which received favourable reviews.[3]

Sibelius withheld this version from publication and made substantial revisions. He deleted much material he felt did not work. The new version premiered on 19 October 1905 with Richard Strauss conducting the Berlin Court Orchestra. Sibelius was not in attendance. Willy Burmester was again asked to be the soloist, but he was again unavailable, so the performance went ahead without him, the orchestra's leader Karel Halíř stepping into the soloist's shoes. Burmester was so offended that he refused ever to play the concerto, and Sibelius re-dedicated it to the Hungarian "wunderkind" Ferenc von Vecsey,[4] who was aged only 12 at the time. Vecsey championed the work, first performing it when he was only 13,[2] although he could not adequately cope with the extraordinary technical demands of the work.[5]

The initial version was noticeably more demanding on the advanced skills of the soloist. It was unknown to the world at large until 1991, when Sibelius's heirs permitted one live performance and one recording, on the BIS record label; both were played by Leonidas Kavakos and conducted by Osmo Vänskä. The revised version still requires a high level of technical facility on the part of the soloist. The original is somewhat longer than the revised, including themes that did not survive the revision. Certain parts, like the very beginning, most of the third movement, and parts of the second, have not changed at all. The cadenza in the first movement is exactly the same for the violin part.

Permission has now been given for a small number of orchestras and soloists to perform the original version in public. The southern hemisphere premiere, only the third public performance,[6] was given on 28 November 2015, by Maxim Vengerov with the Queensland Symphony Orchestra[7] under Nicholas Carter.[6]

Music

This is the only concerto that Sibelius wrote, though he composed several other smaller-scale pieces for solo instrument and orchestra, including the six Humoresques for violin and orchestra.

One noteworthy feature of the work is the way in which an extended cadenza for the soloist takes on the role of the development section in the sonata form first movement. Donald Tovey described the final movement as a "polonaise for polar bears".[8] However, he was not intending to be derogatory, as he went on: "In the easier and looser concerto forms invented by Mendelssohn and Schumann I have not met a more original, a more masterly, and a more exhilarating work than the Sibelius violin concerto".

Much of the violin writing is purely virtuosic, but even the most showy passages alternate with the melodic. This concerto is generally symphonic in scope, departing completely from the often lighter, "rhythmic" accompaniments of many other concertos. The solo violin and all sections of the orchestra have equal voice in the piece.

Scoring

The concerto is scored for solo violin, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani and strings.

Movements

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by Isaac Stern with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy | |

Like most concertos, the work is in three movements:

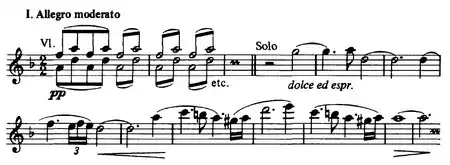

I. Allegro moderato

The first movement opens with a cushion of pianissimo strings pulsating gently. The soloist then enters with a characteristic IV–V–I phrase, in D minor G–A–D. The violin announces the theme and is briefly echoed by clarinet, then continues into developmental material.

More low woodwind and timpani accompany the soloist in several runs. Almost cadenza-like arpeggios, double stops and more runs are accompanied by more woodwind restatements of the theme. The soloist then plays a short quasi-cadenza featuring veloce ascending scales and quick "bottom-middle-top-middle" figurations with rapid string crossings and spiccato. After a rapid ascending figure from the solo violin in broken octaves, the strings then enter brazenly for the first time, announcing a second theme. This second theme is then carried on by the bassoons, and then the clarinets, before the re-entrance of the soloist. The violin plays a gentle elaboration of the main theme, and then a quick arpeggio which ascends into the same second theme played in warm and passionate sixths, and then affettuoso octaves. The soloist softly soars in a slow D♭ arpeggio which leads into the second theme with grace notes an octave lower; following is a trill on one string with the second theme played again, on another string. Another orchestral tutti leads to a violin cadenza, which then opens into the recapitulation, the second theme being played by the violin a semitone higher than before. A long trill from the soloist suddenly transitions into the quick and fiery coda, featuring descending chromatic octaves, rapid and wide shifts to harmonics, and ricochet bowing. An upward cascade of double stops and a final D conclude the first movement.

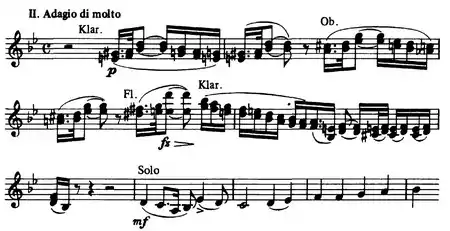

II. Adagio di molto

The second movement is very lyrical. A short introduction by clarinets and oboes leads into a singing solo part (on the G string) over pizzicato strings. Dissonant accompaniments by the brass dominate the first part of the song-like movement.

The middle section has the solo violin playing ascending broken octaves, with the flute as the main voice of the accompaniment, playing descending notes simultaneously. The movement ends with the strings restating the main theme on top of the solo violin.

III. Allegro, ma non tanto

The final movement opens with four bars of rhythmic percussion, with the lower strings playing 'eighth note – sixteenth note – sixteenth note' figures. The violin boldly enters with the first theme on the G string. This first section offers a complete and brilliant display of violin gymnastics with up-bow staccato double-stops and a run with rapid string-crossing, then octaves, that leads into the first tutti.

The second theme is taken up by the orchestra and is almost a waltz; the violin takes up the same theme in variations, with arpeggios and double-stops. Another short section concluding with a run of octaves makes a bridge into a recapitulation of the first theme.

Clarinet and low brass introduce the final section. A passage of harmonics in the violin precedes a sardonic passage of chords and slurred double-stops. A passage of broken octaves leads to an incredibly heroic few lines of double-stops and soaring octaves. A brief orchestral tutti comes before the violin leads things to the finish with a D major scale up, returning down in flatted supertonic (then repeated). A flourish of ascending slur-separate sixteenth notes, punctuated by a resolute D from the violin and orchestra concludes the concerto.

References

- Ruth-Esther Hillila; Barbara Blanchard Hong (1 Jan 1997). Historical Dictionary of the Music and Musicians of Finland. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 198–199. ISBN 9780313277283.

- J. Michael Allsen. "Madison Symphony Orchestra Program Notes". University of Wisconsin-Whitewater. Archived from the original on 4 May 2009.

- Andrew Barnett (2007). Sibelius. Yale University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0300111590.

- Andrew Barnett (2007). Sibelius. Yale University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0300111590.

- Francis Shelton (2008). "Sibelius: Pelléas and Mélisande,Violin Concerto; Beethoven: Symphony No.6 'Pastorale'". MusicalCriticism.com.

- QSO & Maxim Vengerov. Retrieved 5 May 2016

- QSO Media Release: "November a magnificent month of music for QSO", 3 September 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2016

- Tovey, Donald Francis. Essays in Musical Analysis, 1935–39

External links

- Sibelius' Violin Concerto, Op.47: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Sibelius: Violin Concerto, played by Hilary Hahn, conducted by Mikko Franck, with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France