Vladimir Ghika

Vladimir Ghika or Ghica (25 December 1873 – 16 May 1954) was a Romanian diplomat and essayist who, after his conversion from Romanian Orthodoxy to Roman Catholicism, became a priest. He was a member of the princely Ghica family, which ruled Moldavia and Wallachia at various times from the 17th to the 19th century.

Blessed Vladimir Ghika | |

|---|---|

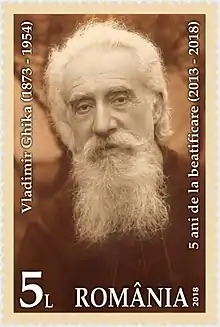

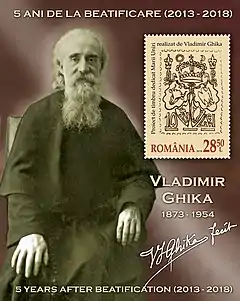

Ghika on a 2018 stamp of Romania | |

| Priest, Bi-Ritual Priest, Prince | |

| Born | 25 December 1873 Constantinople, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 16 May 1954 (aged 80) Jilava, Bucharest, Socialist Republic of Romania |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Eastern Catholic Churches |

| Beatified | 31 August 2013, Bucharest, Romania by Cardinal Angelo Amato, S.D.B., representing Pope Francis |

| Major shrine | St. Basil's Greek Catholic Church, Bucharest, Romania |

| Feast | 16 May |

He died in prison in May 1954 after his arrest by the Communist regime.

Biography

Early life

Vladimir Ghika was born on Christmas Day of 1873 in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey). His father was John Ghika, diplomat, minister plenipotentiary in Turkey ; his mother Alexandrina was born Moret de Blaremberg (van Blarembergue) in a Flemish-Russian family ; he had four brothers and a sister: Gregory, Alexander, George and Ella (who both died at an early age), and Demetrius Ghika (future ambassador and minister of foreign affairs). He was the grandson of the last Prince sovereign of Moldavia, Prince Gregory V Ghika, who ruled from 1849–1856.

He was raised with the Orthodox faith. In 1878, in order to give a good education to the children, the family moved to Toulouse in France. There, they frequented the Protestant community, because the Orthodox church was not represented in the area. Ghika received his Degree in Law in 1895, after which he attended the Paris Faculty of Political Science. At the same time, he frequented courses of Medicine, Botany, Art, Literature, Philosophy, and History.

Ghika returned to Romania due to an attack of angina pectoris and continued his studies in Romania.

Ghika was an alumnus of the College of St. Thomas, the future Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas Angelicum, in Rome. In 1898, he enrolled in the Faculty of Philosophy and Theology. At the Angelicum, Ghika completed a licentiate in Philosophy and a Doctorate in Theology in 1905.[1] Soon after, he converted to the Catholic faith in 1902.

Pilgrimage

.jpeg.webp)

Ghika wanted to become a priest or monk, but Pius X advised him to give up the idea, at least for a while, and to dedicate himself to secular apostolate instead. He became one of the pioneers of the lay apostolate.

After returning to Romania, he dedicated himself to works of charity and opened the first free clinic in Bucharest called Mariae Bethlehem. He also set the foundation for a great hospital and sanatorium named after Saint Vincent de Paul, founded the first free hospital in Romania and the first ambulance, thereby becoming founder of the first Catholic charity work in Romania. He was dedicated to patient care while participating in health services in the Balkan War in 1913, without the fear of cholera in Zimnicea. He was also in charge of diplomatic missions among the Avezzano earthquake victims of tuberculosis of Hospice of Rome during World War I.

On 7 October 1923, Ghika was ordained a priest in Paris by Cardinal Dubois, Archbishop of the city. He served as a priest in France until 1939. Shortly after Ghika was ordained, the Holy See authorized him to celebrate the Byzantine Rite. Prince Ghika thereby became the first bi-ritual Romanian priest.

On 13 May 1931, the Pope appointed Ghika to be an Apostolic Protonotary, but he was reluctant to accept it. He worked worldwide, including Bucharest, Rome, Paris, Congo, Tokyo, Sydney, and Buenos Aires, among others. Later, in jest, Pope Pius XI called him an "apostolic vagabond".[2]

Imprisonment and death

On 3 August 1939, he returned to Romania, where he was caught in the Second World War. He refused to leave Romania at that time so that he could be with the poor and sick. However, he left eventually for the same reason in Bucharest when they started Allied bombing. After the Communists came to power, he also refused to leave on the royal train, for the same reasons.

He was arrested on 18 November 1952, because of his support for the Catholic Church in communion with Rome and his opposition to the schismatic church that the regime was creating. He was charged for "high treason" and threatened, beaten, tortured and processed. Eventually, he was imprisoned at Jilava on 16 May, and he died in 1954 due to the treatment to which he was subjected.

Beatification

Monsignor Vladimir Ghika was proposed for beatification by Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bucharest, based on a dossier with his biography, submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Vatican. On 27 March 2013, Pope Francis declared Vladimir Ghika had been a martyr.[3] He was beatified on 31 August 2013.[4]

Education

- 1893 – School of Toulouse (France)

- 1893–1895 – Faculty of Political Sciences in Paris; attending courses in Medicine, Botany, Art, Literature, Philosophy, History, and Law

- 1895-1898 – Continued his studies in private

- 1898–1905 – Faculty of Philosophy and Theology; obtained a Degree in Philosophy and a Doctorate in Theology

- 1904–1906 – Continues to study History

Writings

Although he had culture and capacity, he avoided producing personal writings. He wrote only because he was forced by circumstances and needs. He did research work in the Vatican archives, publishing some of the results in the Revue Catolique. He also wrote magazine articles in Literary Talk, La Revue Hebdomadaire, Les Études, Le Correspondant, La Revue des Jeunes, and La Documentation Catholique. His short personal meditations were subsequently published in various editions as Pensées pour la suite des jours.

Writings published in French

- Méditation de l'Heure Sainte, first edition, 1912

- Pensées pour la suite des jours, first edition, 1923

- Les intermèdes de Talloires, 1924

- La Messe Byzantine dite de Saint Jean-Chrystome. Nouvelle traduction française adaptée à l'usage courant des fidèles du rite Latin avec commentaire et introduction par le prince Vladimir I. Ghika, 1924

- La visite des pauvres: manuel de la dame de Charité : conférences, first edition, 1923

- Roseau d'Or (Chroniques – Volume VIII), a collection of thoughts (such Pensées pour la suite des jours), 1928

- La Sainte Vierge et le Saint Sacrement, 1929

- Vigia (book IV), a collection of thoughts (such Pensées pour la suite des jours), 1930

- La Femme adultère. Un prologue, un acte, un épilogue. 2e édition, 1931

- La souffrance, first edition, 1932

- La Liturgie du prochain, first edition, 1932

- La Présence de Dieu, first edition, 1932

- Derniers témoignages [seem] Mgr Vladimir Ghika. Presentes par Yvonne Estienne, 1970; posthumous publication that collects various other unpublished thoughts

Writings published in Romanian

- Our Lady and the Holy Sacrament. Speech delivered by Monsignor Ghika opening in November 1928 Eucharistic Congress in Sydney, Australia

- Adulteress. Gospel Mystery comprising a prologue, an act, an epilogue. Pieasă theater

- Thoughts For the Days Ahead

- Spiritual Conversation

- Interludes in Talloires

- Last witness, Vladimir Ghika, pref. Yvonne Estienne

- Posthumous fragments. Institute of previously unpublished archive

- "Vladimir Ghika" (translation of documents unpublished)

Bibliography

- Biography

- Vladimir Ghika. Profesor de speranță, Francisca Băltăceanu, Andrei Brezianu, Monica Broșteanu, Emanuel Cosmovici, Luc Verly, prefață de IPS Ioan Robu, Editura ARCB, București 2013.

- Vladimir Ghika, professeur d'espérance, Francesca Baltaceanu et Monica Brosteanu, préface de Mgr Philippe Brizard, Cerf, 2013

- Vladimir Ghika. Prințul cerșetor de iubire pentru Cristos, Anca Mărtinaș, Editrice Velar, Editura ARCB, București 2013.

- Vladimir Ghika. Il principe mendicante di amore per Cristo, Anca Mărtinaș, Editrice Velar, Editrice ELLEDICI, Gorle, 2013.

- Monseniorul: amintiri și documente din viața Monseniorului Ghika în România, Horia Cosmovici, Editura Galaxia Gutenberg, Târgu Lăpuș, 2011.

- Mgr Vladimir Ghika. Prince, prêtre et martyr, Charles Molette, AED, Paris, 2007.

- Vladimir Ghika. L'Angelo della Romania, in Il nono libro dei Ritratti di santi', Antonio Maria Sicari o.c.d., Jaka Book, 2006.

- Monseniorul: amintiri din viața de apostolat, Horia Cosmovici, Editura MC, București, 1996.

- Principe, sacerdore e martire. Vladimir Ghika, Jean Daujat, Edizioni Messaggero di Padova, Padova, 1996.

- Prince et martyr, l’apôtre du Danube, Mgr Vladimir Ghika, Hélène Danubia, Pierre Tequi, Paris, 1993.

- La memoire des silence, Vladimir Ghika 1873–1954, Élisabeth de Miribel, Librarie Artème Fayard, 1987.

- Une flamme dans le vitrail. Souvenirs sur Mgr. Ghika, Yvonne Estienne, Editions Du Chalet, Lyon,1963.

- Vladimir Ghika, Prince et Berger, Susane-Marie Durand, Castermann, 1962.

- Une âme de feu, monseigneur Vladimir Ghika, Michel de Galzain, Éditions Beauchesne, 1961.

- L’apôtre du XX-em siècle, Vladimir Ghika, Jean Daujat, La Palatine-Plon, 1956.

- Les Convertis du 20e siècle – Du Palais à l'autel et à la geôle. Le Prince Vladimir Ghika, de Pierre Gherman, Bruxelles, 1954.

- Monseniorul Vladimir Ghika -Schita de portret European de Stefan J. Fay – Continent 2006

- Studies

- „Rugați-vă toți pentru mine...” Monseniorul Vladimir Ghika și martiriul său, Florina-Aida Bătrînu, ARCB, București, 2013.

- O lumină în întuneric: Monseniorul Vladimir Ghika, Mihaela Vasiliu, ARCB, București, 2012.

- Une lumière dans les ténébres. Mgr Vladimir Ghika, Mihaela Vasiliu, Cerf, Paris, 2011.

- Mgr Vladimir Ghika apôtre et martyr. Actes du colloque à la mémoire de Mgr Vladimir Ghika. Octobre 2010, Paris, ABMVG, Paris 2011.

- A trăit și a murit ca un sfânt! Mons. Vladimir Ghika 1873–1954, ed. Ioan Ciobanu, ARCB, București, 2003.

References

- Holy Father declares Angelicum alumnus "venerable". 4 June 2013

- Andrei Gotia (January 2015) "Blessed Vladimir Ghika: prince, priest, and martyr". Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture.

- "Pope approves first decrees on future saints". Rome Reports. 29 March 2013. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013.

- Rocca, Francis X. (28 March 2013). "Pope recognises martyrs who died at the hands of communist and fascist regimes". Catholic Herald. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vladimir Ghika. |

- Vladimir Ghika (in Romanian)

- Blog Postulation (in Romanian)

- Archdiocese of Bucharest (in Romanian)

- Lagrasse Canons

- To My Brother in Exile (2009)

- Serban Nichifor, Missa Beatus Vladimir Ghika (2017)