Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov[lower-alpha 1] (/ˈmɒlətɒf, ˈmoʊ-/;[1] né Skryabin;[lower-alpha 2] (OS 25 February) 9 March 1890 – 8 November 1986)[2] was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik, and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s. Molotov served as Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars from 1930 to 1941, and as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1939 to 1949 and from 1953 to 1956.

Vyacheslav Molotov Вячеслав Молотов | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vyacheslav Molotov in 1936 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 19 December 1930 – 6 May 1941 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Alexei Rykov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Joseph Stalin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 August 1942 – 29 June 1957 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Joseph Stalin Georgy Malenkov Nikolai Bulganin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolai Voznesensky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Bulganin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 3 May 1939 – 4 March 1949 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Joseph Stalin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Maxim Litvinov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Andrey Vyshinsky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 March 1953 – 1 June 1956 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Georgy Malenkov Nikolai Bulganin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Andrey Vyshinsky | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Dmitri Shepilov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin 9 March 1890 Kukarka, Russian Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 8 November 1986 (aged 96) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship | Soviet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Russian | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1906–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1961) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Vyacheslav Nikonov (grandson) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

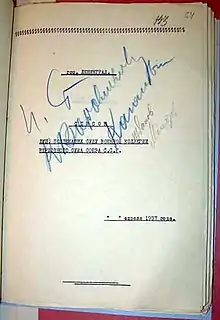

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Born in Kukarka, Molotov joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1906 and supported Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction. He was twice arrested and exiled for revolutionary activities. As an editor of Pravda, Molotov opposed Alexander Kerensky's Provisional Government after the February Revolution of 1917. He later became a member of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee, which planned the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

After the revolution, Molotov worked in Ukraine before being recalled to Moscow in 1921, where he became a full member of the Central Committee. A staunch supporter and protégé of Joseph Stalin, Molotov achieved greater prominence following Lenin's death and Stalin's rise to power. He was made a full member of the Politburo in 1926, appointed First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party in 1928, and in 1930 he became the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (Premier of the Soviet Union). In the latest capacity, Molotov oversaw the collectivization of Soviet Union's agricultural sector and the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan. He played a central role during the Great Purge in the 1930s, signing 373 execution lists, more than any other Soviet official including Stalin. He would later justify his role in the Great Purge by stating that although it was excessive at times, it was necessary to purge the party of reactionary elements.[3]

Molotov was appointed People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs in May 1939, and subsequently became the principal Soviet signatory of the German–Soviet non-aggression pact (also known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact). During the Great Patriotic War, Molotov was the deputy chairman of the State Defense Committee. He helped to negotiate the Anglo-Soviet Treaty of 1942, a Lend-Lease treaty with the US in the same year, and accompanied Stalin to the 1943 Tehran Conference, the 1945 Yalta Conference and the Potsdam Conference following German defeat. He also represented the Soviet Union at the San Francisco Conference, which led to the creation of the United Nations. After the war, he became noted in the West for his diplomatic skills and general hostility.

Molotov retained his place as a leading Soviet diplomat and politician until March 1949, when he fell out of Stalin's favour and lost the foreign affairs ministry leadership to Andrei Vyshinsky. Molotov's relationship with Stalin deteriorated further, with Stalin criticizing Molotov in a speech to the 19th Party Congress. He was reappointed Minister of Foreign Affairs after Stalin's death in 1953, but was staunchly opposed to Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinization policy, which resulted in his eventual dismissal from all positions and expulsion from the party in 1961. Molotov defended Stalin's policies and legacy until his death in 1986, and harshly criticized Stalin's successors, especially Khrushchev.

Biography

Early life and career (1890–1930)

Molotov was born Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Skryabin in the village of Kukarka, Yaransk Uyezd, Vyatka Governorate (now Sovetsk in Kirov Oblast), the son of a merchant. Contrary to a commonly repeated error, he was not related to the composer Alexander Scriabin.[4] Throughout his teen years, he was described as "shy" and "quiet", always assisting his father with his business. He was educated at a secondary school in Kazan, and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1906, soon gravitating toward that organisation's radical Bolshevik faction, headed by V. I. Lenin.[5]

Skryabin took the pseudonym "Molotov", derived from the Russian word molot (sledge hammer), since he believed that the name had an "industrial" and "proletarian" ring to it.[5] He was arrested in 1909 and spent two years in exile in Vologda. In 1911, he enrolled at St Petersburg Polytechnic. Molotov joined the editorial staff of a new underground Bolshevik newspaper called Pravda, meeting Joseph Stalin for the first time in association with the project.[6] This first association between the two future Soviet leaders proved to be brief, however, and did not lead to an immediate close political association.[6]

Molotov worked as a so-called "professional revolutionary" for the next several years, writing for the party press and attempting to better organize the underground party.[6] He moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow in 1914 at the time of the outbreak of World War I.[6] It was in Moscow the following year that Molotov was again arrested for his party activity, this time being deported to Irkutsk in eastern Siberia.[6] In 1916, he escaped from his Siberian exile and returned to the capital city, now called Petrograd by the Tsarist regime, which thought the name St. Petersburg sounded excessively German.[6]

Molotov became a member of the Bolshevik Party's committee in Petrograd in 1916. When the February Revolution occurred in 1917, he was one of the few Bolsheviks of any standing in the capital. Under his direction Pravda took to the "left" to oppose the Provisional Government formed after the revolution. When Joseph Stalin returned to the capital, he reversed Molotov's line;[7] but when the party leader Lenin arrived, he overruled Stalin. Despite this, Molotov became a protégé of and close adherent to Stalin, an alliance to which he owed his later prominence.[8] Molotov became a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee which planned the October Revolution, which effectively brought the Bolsheviks to power.[9]

In 1918, Molotov was sent to Ukraine to take part in the civil war then breaking out. Since he was not a military man, he took no part in the fighting. In 1920, he became secretary to the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Bolshevik Party and married the Soviet politician Polina Zhemchuzhina.[10] Lenin recalled him to Moscow in 1921, elevating him to full membership of the Central Committee and Orgburo, and putting him in charge of the party secretariat. He was voted in as a non-voting member of the Politburo in 1921 and held the office of Responsible Secretary.

His Responsible Secretaryship was criticised by Lenin and Leon Trotsky, with Lenin noting his "shameful bureaucratism" and stupid behaviour.[4] On the advice of Molotov and Nikolai Bukharin, the Central Committee decided to reduce Lenin's work hours.[11] In 1922, Stalin became General Secretary of the Bolshevik Party with Molotov as the de facto Second Secretary. As a young follower, Molotov admired Stalin but did not refrain from criticizing him.[12] Under Stalin's patronage, Molotov became a member of the Politburo in 1926.[8]

During the power struggles which followed Lenin's death in 1924, Molotov remained a loyal supporter of Stalin against his various rivals: first Leon Trotsky, later Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, and finally Nikolai Bukharin. Molotov became a leading figure in the "Stalinist centre" of the party, which also included Kliment Voroshilov and Sergo Ordzhonikidze.[13] Trotsky and his supporters underestimated Molotov, as did many others. Trotsky called him "mediocrity personified", whilst Molotov himself pedantically corrected comrades referring to him as 'Stone Arse' by saying that Lenin had actually dubbed him 'Iron Arse'.[4]

However, this outward dullness concealed a sharp mind and great administrative talent. He operated mainly behind the scenes and cultivated an image of a colourless bureaucrat – for example, he was the only Bolshevik leader who always wore a suit and tie.[14] In 1928, Molotov replaced Nikolai Uglanov as First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party and held that position until 15 August 1929.[15] In a lengthy address to the Central Committee in 1929, Molotov told the members the Soviet government would initiate a compulsory collectivisation campaign to solve the agrarian backwardness of Soviet agriculture.[16]

Molotov and his wife had two daughters: Sonia, adopted in 1929, and Svetlana, born in 1930.[10]

Premiership (1930–1941)

During the Central Committee plenum of 19 December 1930, Molotov succeeded Alexey Rykov as the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (the equivalent of a Western head of government).[17] In this post, Molotov oversaw agricultural collectivisation under Stalin's regime. Molotov also oversaw the implementation of the First Five-Year Plan for rapid industrialisation.[18]

Sergei Kirov, head of the Party organisation in Leningrad, was killed in 1934;[19] some believed Stalin ordered his death. Evidence that supports Stalin's involvement and evidence that does not is set out in J. Holroyd-Doveton's biography of Maxim Litvinov.[20]

Following Kirov's murder, the next significant although unpublicised event was Stalin's apparent rift with Molotov.[21] On 19 March 1936 Molotov gave an interview with the editor of Le Temps concerning improved relations with Nazi Germany.[22] Although Litvinov had made similar statements in 1934, and even visited Berlin that year, this was before Germany's occupation of the Rhineland.[21] Watson believes Molotov's statement on foreign policy gave offense to Stalin. Molotov had made it clear that improved relations with Hitler's Germany could develop only if Germany's policy changed. Molotov then stated that one of the best ways for Germany to improve relations was by re-joining the League of Nations, but even that was not sufficient. Germany still had to give proof 'of its respect for international obligations in keeping with the real interests of peace in Europe and peace generally'.[23] As Litvinov during 1933 and 1934 had done his best to prevent the cordial relations created by Rapallo from declining, some do not think Litvinov would have disapproved of that statement; and if German policy had changed, Litvinov would have been delighted. However, Robert Conquest, unlike Watson, believed that the reason for Stalin's temporary rift with Molotov was not concerned with foreign policy but stemmed from the fact that Stalin was incensed with Molotov for attempting to try and dissuade Stalin from staging the famous trials against the old colleagues of Lenin.[24] Molotov, in the same interview, denied the continued existence of internal enemies except for a few isolated cases. Holroyd-Doveton thinks this is more likely to have given offense to Stalin.[21]

Watson, Orlov, and Conquest believe that there was a rift between Molotov and Stalin because Molotov's name was omitted from the list of those whom the conspirators were planning to kill, while all other prominent leaders were included. Then, in May 1936, Molotov went to the Black Sea on an extended holiday under careful NKVD supervision until the end of August, when apparently Stalin changed his mind and ordered Molotov's return.[25]

Kirov's death triggered a second crisis, the Great Purge.[26] In 1938, out of the 28 People's Commissars in Molotov's Government, 20 were executed on the orders of Molotov and Stalin.[27] The purges were carried out by Stalin's successive police chiefs;[28] Nikolai Yezhov was the chief organiser, and Kliment Voroshilov, Lazar Kaganovich, and Molotov were intimately involved in the processes.[29] Stalin frequently required Molotov and other Politburo members to sign the death warrants of prominent purge victims, and Molotov always did so without question.[30]

There is no record of Molotov attempting to moderate the course of the purges or even to save individuals, as some other Soviet officials did. During the Great Purge, he approved 372 documented execution lists, more than any other Soviet official, including Stalin. Molotov was one of the few with whom Stalin openly discussed the purges.[31] Although Molotov and Stalin signed a public decree in 1938 that disassociated them from the ongoing Great Purge,[32] in private, and even after Stalin's death, Molotov supported the Great Purge and the executions carried out by his government.[33]

Despite the great human cost,[34] the Soviet Union under Molotov's nominal premiership made great strides in the adoption and widespread implementation of agrarian and industrial technology. The rise of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany precipitated the development of a modern armaments industry on the orders of the Soviet government.[35] Ultimately, it was this arms industry, along with American Lend-Lease aid, which helped the Soviet Union prevail in World War II.[36]

Set against this, the purges of the Red Army leadership, in which Molotov participated, weakened the Soviet Union's defence capacity and contributed to the military disasters of 1941 and 1942, which were mostly caused by unreadiness for war.[37] The purges also led to the dismantling of privatised agriculture and its replacement by collectivised agriculture. This left a legacy of chronic agricultural inefficiencies and under-production which the Soviet regime never fully rectified.[38]

Molotov was reported to be a vegetarian and teetotaler by American journalist John Gunther in 1938.[39] However, Milovan Djilas claimed that Molotov "drank more than Stalin"[40] and did not note his vegetarianism despite attending several banquets with him.

Minister of Foreign Affairs (1939–1949)

In 1939, following the 1938 Munich Agreement and Hitler's subsequent invasion of Czechoslovakia, Stalin believed that Britain and France would not be reliable allies against German expansion so he instead sought to conciliate Nazi Germany.[41] In May 1939, Maxim Litvinov, the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs, was dismissed; it is not certain why Litvinov was dismissed but it was discussed in Ch. 14 of J. Holroyd-Doveton's biography of Maxim Litvinov.[42] Molotov was appointed to succeed him.[43] Relations between Molotov and Litvinov had been bad,[44] which is corroborated by a number of sources. Maurice Hindus, in 1954, was perhaps the first person outside the Soviet Union to understand this hostility. In his book Crisis in the Kremlin, he states:

It is well known in Moscow that Molotov always detested Litvinov. Molotov's detestation for Litvinov was purely of a personal nature. No Moscovite I have ever known, whether a friend of Molotov or of Litvinov, has ever taken exception to this view. Molotov was always resentful of Litvinov's fluency in French, German and English, as he was distrustful of Litvinov's easy manner with foreigners. Never having lived abroad, Molotov always suspected that there was something impure and sinful in Litvinov's broad mindedness and appreciation of Western civilisation.[45]

Although Litvinov never mentioned his relationship with Molotov in the foreign commissariat, Narkomindel press officer Genedin states: even though Litvinov never referred to their relationship (between Litvinov and Molotov) it was nevertheless well known it was bad. Litvinov had no respect for a small minded intriguer and accomplice in terror like Molotov, and Molotov for his part had no love for Litvinov, who incidentally was the one people's commissioner to retain his independence.[46]

Molotov was succeeded in his post as Premier by Stalin.[47]

At first, Hitler rebuffed Soviet diplomatic hints that Stalin desired a treaty; but in early August 1939, Hitler authorised Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop to begin serious negotiations. A trade agreement was concluded on 18 August; and on 22 August, Ribbentrop flew to Moscow to conclude a formal non-aggression treaty. Although the treaty is known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, it was Stalin and Hitler, and not Molotov and Ribbentrop, who decided the content of the treaty.

The most important part of the agreement was the secret protocol, which provided for the partition of Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union and for the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia (then part of Romania, now Moldova).[43] This protocol gave Hitler the green light for his invasion of Poland, which began on 1 September.[48] On 5 March 1940, Lavrentiy Beria gave Molotov, along with Anastas Mikoyan, Kliment Voroshilov and Stalin, a note proposing the execution of 25,700 Polish officers and anti-Soviets, in what has become known as the Katyn massacre.[47]

Under the Pact's terms, Hitler was, in effect, given authorisation to occupy two-thirds of Western Poland, as well as Lithuania. Molotov was given a free hand in relation to Finland. In the Winter War that ensued, a combination of fierce Finnish resistance and Soviet mismanagement resulted in Finland losing parts of its territory, but not its independence.[49] The Pact was later amended to allocate Lithuania to the Soviet sphere in exchange for a more favourable border in Poland. These annexations led to horrific suffering and loss of life in the countries occupied and partitioned by the two dictatorships.[50]

In November 1940, Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to meet Ribbentrop and Adolf Hitler. In January 1941, the British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden visited Turkey in an attempt to get the Turks to enter the war on the Allies' side. Though the purpose of Eden's visit was anti-German rather than anti-Soviet, Molotov assumed otherwise, and in a series of conversations with the Italian Ambassador Augusto Rosso, Molotov claimed that the Soviet Union would soon be faced with an Anglo–Turkish invasion of the Crimea. The British historian D.C. Watt argued that, on the basis of Molotov's statements to Rosso, it would appear that, in early 1941, Stalin and Molotov viewed Britain rather than Germany as the principal threat.[51]

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact governed Soviet–German relations until June 1941 when Hitler, having occupied France and neutralised Britain, turned east and attacked the Soviet Union.[52] Molotov was responsible for telling the Soviet people of the attack, when he instead of Stalin announced the war. His speech, broadcast by radio on 22 June, characterised the Soviet Union in a role similar to that articulated for Britain by Winston Churchill in his early wartime speeches.[53] The State Defence Committee was established soon after Molotov's speech; Stalin was elected chairman and Molotov was elected deputy chairman.[54]

Following the German invasion, Molotov conducted urgent negotiations with Britain and, later, the United States for wartime alliances. He took a secret flight to Glasgow, Scotland, where he was greeted by Eden. This risky flight, in a high altitude Tupolev TB-7 bomber, flew over German-occupied Denmark and the North Sea. From there, he took a train to London to discuss with the British government the possibility of opening a second front against Germany.

After signing the Anglo–Soviet Treaty of 1942 on 26 May, Molotov left for Washington, D.C., in the United States. Molotov met with Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President of the United States, and ratified a Lend-Lease Treaty between the USSR and the US. Both the British and the United States government, albeit vaguely, promised to open up a second front against Germany. On his flight back to the USSR his plane was attacked by German fighters, and then later by Soviet fighters.[55]

When Beria told Stalin about the Manhattan Project and its importance, Stalin handpicked Molotov to be the man in charge of the Soviet atomic bomb project. However, under Molotov's leadership the bomb, and the project itself, developed very slowly, and Molotov was replaced by Beria in 1944 on the advice of Igor Kurchatov.[56] When Harry S. Truman, the American president, told Stalin that the Americans had created a bomb never seen before, Stalin relayed the conversation to Molotov and told him to speed up development. On Stalin's orders, the Soviet government substantially increased investment in the project.[57][58] In a collaboration with Kliment Voroshilov, Molotov contributed both musically and lyrically to the 1944 version of the Soviet national anthem. Molotov asked the writers to include a line or two about peace. Molotov's and Voroshilov's role in the making of the new Soviet anthem was, in the words of historian Simon Sebag-Montefiore, acting as music judges for Stalin.[59]

Molotov accompanied Stalin to the Teheran Conference in 1943,[60] the Yalta Conference in 1945,[61] and, following the defeat of Germany, the Potsdam Conference.[62] He represented the Soviet Union at the San Francisco Conference, which created the United Nations.[63] Even during the period of wartime alliance, Molotov was known as a tough negotiator and a determined defender of Soviet interests. Molotov lost his position of First Deputy chairman on 19 March 1946, after the Council of People's Commissars was reformed as the Council of Ministers.

From 1945 to 1947, Molotov took part in all four conferences of foreign ministers of the victorious states in World War II. In general, he was distinguished by an uncooperative attitude towards the Western powers. Molotov, at the direction of the Soviet government, condemned the Marshall Plan as imperialistic and claimed it was dividing Europe into two camps, one capitalist and the other communist. In response, the Soviet Union, along with the other Eastern Bloc nations, initiated what is known as the Molotov Plan. The plan created several bilateral relations between the states of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union; and later evolved into the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA).[64]

In the postwar period, Molotov's power began to decline. A clear sign of his precarious position was his inability to prevent the arrest for "treason", in December 1948, of his Jewish wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina, whom Stalin had long distrusted.[65] Molotov never stopped loving his wife, and it is said he ordered his maids to make dinner for two every evening to remind him that, in his own words, "she suffered because of me".[66]

Polina Zhemchuzhina befriended Golda Meir, who arrived in Moscow in November 1948 as the first Israeli envoy to the USSR.[67] According to a close collaborator of Molotov, Vladimir Ivanovich Yerofeyev, Meir met privately with Polina, who had been her schoolmate in St. Petersburg. Immediately afterwards, Polina was arrested and accused of ties with Zionist organisations. She was imprisoned for a year in the Lubyanka, after which she was exiled for three years in an obscure Russian city. Molotov had no communication with her, save for the scant news that he got from Beria, whom he loathed. Polina was freed immediately after the death of Stalin.[68] According to Erofeev, Molotov said of her: "She's not only beautiful and intelligent, the only woman minister in the Soviet Union; she's also a real Bolshevik, a real Soviet person."

However, Molotov now, according to Stalin's daughter, became very subservient to his wife.[69] Molotov yessed his wife in the same way he had previously yessed Stalin.[70]

In 1949, Molotov was replaced as Foreign Minister by Andrey Vyshinsky, although retaining his position as First Deputy Premier and membership in the Politburo.[66]

Post-war career (1949–1962)

At the 19th Party Congress in 1952, Molotov was elected to the replacement for the Politburo, the Presidium, but was not listed among the members of the newly established secret body known as the Bureau of the Presidium; indicating that he had fallen out of Stalin's favour.[71] At the 19th Congress, Molotov and Anastas Mikoyan were said by Stalin that "There has been criticism of comrade Molotov and Mikoyan by the Central Committee"[72], mistakes including the publication of a wartime speech by Winston Churchill favourable to the Soviet Union's wartime efforts.[73] Both Molotov and Mikoyan were falling out of favour rapidly, with Stalin telling Beria, Khrushchev, Malenkov and Nikolai Bulganin that he did not want to see Molotov and Mikoyan around anymore. At his 73rd birthday, Stalin treated both with disgust.[74] In his speech to the 20th Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev told delegates that Stalin had plans for "finishing off" Molotov and Mikoyan in the aftermath of the 19th Congress.[75]

Following Stalin's death, a realignment of the leadership strengthened Molotov's position. Georgy Malenkov, Stalin's successor in the post of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, reappointed Molotov as Minister of Foreign Affairs on 5 March 1953.[76] Although Molotov was seen as a likely successor to Stalin in the immediate aftermath of his death, he never sought to become leader of the Soviet Union.[77] A Troika was established immediately after Stalin's death, consisting of Malenkov, Beria, and Molotov,[78] but ended when Malenkov and Molotov deceived Beria.[79] Molotov supported the removal and later the execution of Beria on the orders of Khrushchev.[80] The new Party Secretary, Khrushchev, soon emerged as the new leader of the Soviet Union. He presided over a gradual domestic liberalisation and a thaw in foreign policy, as was manifest in a reconciliation with Josip Broz Tito's government in Yugoslavia, which Stalin had expelled from the communist movement. Molotov, an old-guard Stalinist, seemed increasingly out of place in the new environment,[81] but he represented the Soviet Union at the Geneva Conference of 1955.[82]

Molotov's position became increasingly tenuous after February 1956, when Khrushchev launched an unexpected denunciation of Stalin at the 20th Congress of the Communist Party. Khrushchev attacked Stalin both over the purges of the 1930s and the defeats of the early years of World War II, which he blamed on Stalin's overly trusting attitude towards Hitler and his purges of the Red Army command structure. As Molotov was the most senior of Stalin's collaborators still in government and had played a leading role in the purges, it became evident that Khrushchev's examination of the past would probably result in Molotov's fall from power, and he became the leader of an old guard faction that sought to overthrow Khrushchev.[83]

In June 1956, Molotov was removed as Foreign Minister;[84] on 29 June 1957, he was expelled from the Presidium (Politburo) after a failed attempt to remove Khrushchev as First Secretary. Although Molotov's faction initially won a vote in the Presidium, 7–4, to remove Khrushchev, the latter refused to resign unless a Central Committee plenum decided so.[85] In the plenum, which met from 22 to 29 June, Molotov and his faction were defeated.[83] Eventually he was banished, being made ambassador to the Mongolian People's Republic.[85] Molotov and his associates were denounced as "the Anti-Party Group" but, notably, were not subject to such unpleasant repercussions as had been customary for denounced officials in the Stalin years. In 1960, he was appointed Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency, which was seen as a partial rehabilitation.[86] However, after the 22nd Party Congress in 1961, during which Khrushchev carried out his de-Stalinisation campaign, including the removal of Stalin's body from Lenin's Mausoleum, Molotov (along with Lazar Kaganovich) was removed from all positions and expelled from the Communist Party.[71] In 1962, all of Molotov's party documents and files were destroyed by the authorities.[87]

In retirement, Molotov remained unrepentant about his role under Stalin's rule.[88] He suffered a heart attack in January 1962. After the Sino-Soviet split, it was reported that he agreed with the criticisms made by Mao Zedong of the supposed "revisionism" of Khrushchev's policies. According to Roy Medvedev, Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva recalled Molotov's wife telling her: "Your father was a genius. There's no revolutionary spirit around nowadays, just opportunism everywhere"[89] and "China's our only hope. Only they have kept alive the revolutionary spirit".[90]

Later years and death (1962–1986)

In 1968, United Press International reported that Molotov had completed his memoirs, but that they would likely never be published.[91] The first signs of Molotov's rehabilitation were seen during Leonid Brezhnev's rule, when information about him was again allowed to be included in Soviet encyclopedias. His connection, support and work in the Anti-Party Group were mentioned in encyclopedias published in 1973 and 1974, but eventually disappeared altogether by the mid-to-late-1970s. Later, Soviet leader Konstantin Chernenko further rehabilitated Molotov;[92] in 1984, Molotov was even allowed to seek membership in the Communist Party.[93] A collection of interviews with Molotov from 1985 was published in 1994 by Felix Chuev as Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics.

In June 1986, Molotov was hospitalized in Kuntsevo Hospital in Moscow, where he eventually died, during the rule of Mikhail Gorbachev, on 8 November 1986.[94][95] During his life, Molotov suffered seven heart attacks, yet survived to the age of 96. At the time of his death, he was the last surviving major participant in the events of 1917. He was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.[88]

Legacy

Molotov, like Stalin, was pathologically mistrustful of others, and because of it, much crucial information disappeared. As Molotov once said, "One should listen to them, but it is necessary to check up on them. The intelligence officer can lead you to a very dangerous position... There are many provocateurs here, there, and everywhere."[96] Molotov continued to claim, in a series of published interviews, that there never was a secret territorial deal between Stalin and Hitler during the Nazi–Soviet Pact.[97] Like Stalin, he never recognised the Cold War as an international event. He saw the Cold War as, more or less, the everyday conflict between communism and capitalism. He divided the capitalist countries into two groups, the "smart and dangerous imperialists" and the "fools".[98] Before his retirement, Molotov proposed establishing a socialist confederation with the People's Republic of China (PRC); Molotov believed socialist states were part of a bigger, supranational entity.[99] In retirement, Molotov criticised Nikita Khrushchev for being a "right-wing deviationist".[100]

The Molotov cocktail is a term coined by the Finns during the Winter War, as a generic name used for a variety of improvised incendiary weapons.[101] During the Winter War, the Soviet air force made extensive use of incendiaries and cluster bombs against Finnish civilians, troops and fortifications. When Molotov claimed in radio broadcasts that they were not bombing, but rather delivering food to the starving Finns, the Finns started to call the air bombs Molotov bread baskets.[102] Soon they responded by attacking advancing tanks with "Molotov cocktails," which were "a drink to go with the food." According to Montefiore, the Molotov cocktail was one part of Molotov's cult of personality that the vain Premier surely did not appreciate.[103]

Winston Churchill in his wartime memoirs lists many meetings with Molotov. Acknowledging him as a "man of outstanding ability and cold-blooded ruthlessness", Churchill concluded: "In the conduct of foreign affairs, Mazarin, Talleyrand, Metternich, would welcome him to their company, if there be another world to which Bolsheviks allow themselves to go."[104]

At the end of 1989, two years before the final collapse of the Soviet Union, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union and Mikhail Gorbachev's government formally denounced the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[105]

In January 2010, a Ukrainian court accused Molotov and other Soviet officials of organizing a man-made famine in Ukraine in 1932–33. The same Court then ended criminal proceedings against them, as the trial would be posthumous.[106]

Portrayals in media

Luther Adler portrayed Molotov in the 1958 Playhouse 90 episode The Plot to Kill Stalin.

Michael Palin was cast as Molotov in the 2017 satire The Death of Stalin.

Decorations and awards

- Hero of Socialist Labour

- Four Orders of Lenin (including 1945)

- Order of the October Revolution

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Order of the Badge of Honour

- Medal "For the Defence of Moscow"

- Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945"

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow"

See also

Notes

- Russian: Вячеслав Михайлович Молотов, IPA: [vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ ˈmolətəf].

- Russian: Скрябин.

References

- "Molotov". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Jessup, John E. (1998). An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313281129.

- Chuev, Felix (1991). Molotov Remembers: Inside Kremlin Politics. ISBN 9781461694915.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 40.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. p. 5. ISBN 9781612344294

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2012). Molotov: Stalin's Cold Warrior. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. p. 6. ISBN 9781612344294

- Молотов, Вячеслав Михайлович [Mikhailovich Molotov, Vyacheslav] (in Russian). warheroes.ru. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 36.

- Molotov, Vyacheslav; Chuev, Felix; Resis, Albert (1993). Molotov remembers: inside Kremlin politics: conversations with Felix Chuev. I.R. Dee. p. 94. ISBN 1-56663-027-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Written at Moscow. "Mrs. Molotov Dies in Moscow; WIfe of Ex-Premier Was 76". The New York Times. New York City. United Press International. 4 May 1970. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Service 2003, p. 151.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 40–41.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 36–37.

- Rywkin, Michael (1989). Soviet Society Today. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 159–160. ISBN 9780873324458.

- Service 2003, p. 176.

- Service 2003, p. 179.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 63–64.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 45 and 58.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 148–149.

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publications. pp. 405–408. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publications. p. 408. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Stati I Rechi 1935-1936. pp. 231–232.

- Watson, Derek (1996). Molotov and the Sovnarkon 1930–1941. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 16. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-24848-3. ISBN 978-1-349-24848-3.

- Conquest, Robert (1968). The Great Terror. UK: Oxford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0195055801.

- Watson, Derek (1996). Molotov and the Sovnarkon 1930–1941. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 162. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-24848-3. ISBN 978-1-349-24848-3.

- Brown 2009, p. 71.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 244.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 222.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 240.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 237.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 225.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 289.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 260.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 125.

- Scott Dunn, Walter (1995). The Soviet economy and the Red Army, 1930–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 22. ISBN 0-275-94893-5.

- Davies, Robert William; Harrison, Mark; Wheatcroft, S.G. (1994). The Economic transformation of the Soviet Union, 1913–1945. Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–251. ISBN 0-521-45770-X.

- Brown 2009, p. 65.

- "Stalin's legacy". country-data.com. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Chen, C. Peter. Vyacheslav Molotov. In 1938 American journalist John Gunther wrote: " He [Molotov] is... a man of first-rate intelligence and influence. Molotov is a vegetarian and a teetotaler."

- Djilas, Milovan (1962) Conversations with Stalin. Translated by Michael B. Petrovich. Rupert Hart-Davis, Soho Square London 1962, pp. 59.

- Brown 2009, pp. 90–91.

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). "Ch. 14". Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publication. pp. 351–359. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Service 2003, p. 256.

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Litvinov: A Biography. Woodland Publication. p. 488. ISBN 9780957296107.

- Hindus, Maurice Gerschon (1953). Crisis in the Kremlin. Doubleday. p. 48.

- Medvedev, Roy (1984). All Stalin's Men. Anchor Press/Doubleday. p. 488. ISBN 0-385-18388-7.

- Brown 2009, p. 141.

- Brown 2009, pp. 90–92.

- Service 2003, pp. 256–257.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 320, 322 and 342.

- Cameron Watt, Donald (2004). Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 276–286. ISBN 0-415-14435-3.

- Service 2003, pp. 158–160.

- Service 2003, p. 261.

- Service 2003, p. 262.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 417–418.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 508.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 510.

- Zhukov, Georgi Konstantinovich (1971). The Memoirs of Marshal Zhukov. New York: Delacorte Press.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 468.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 472.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 489.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 507.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 477.

- Roberts, Geoffrey (1999). The Soviet Union in world politics: coexistence, revolution, and cold war, 1945–1991. Routledge. pp. 284–285. ISBN 0-415-14435-3.

- Brown 2009, pp. 199–201.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 604.

- Johnson, Paul (1987), A History of the Jews. Associated University Presse. p. 527

- Montefiore 2005, p. 666.

- Holroyd-Doveton, John (2013). Maxim Livinov: A Biography. Woodland Publications. p. 493.

- Alliluyeva, Svetlana (1969). Only One Year. p. 384.

- Brown 2009, p. 231.

- Unpublished speech by Stalin on 16th October 1952 Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{lang-en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. Accessed on 3rd February 2021

- Montefiore 2005, p. 640.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 645–647.

- "Russia: The Survivor". Time. 16 September 1957. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 662.

- Brown 2009, p. 227.

- Marlowe, Lynn Elizabeth (2005). GED Social Studies: The Best Study Series for GED. Research and Education Association. p. 140. ISBN 0-7386-0127-6.

- Taubman, William (2003). Khrushchev: The Man and His Era. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 258. ISBN 0-393-32484-2.

- Brown 2009, p. 666.

- Brown 2009, pp. 236–237.

- Bischof, Günter; Dockrill, Saki (2000). Cold War respite: the Geneva Summit of 1955. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 0-8071-2370-6.

- Montefiore 2005, pp. 666–667.

- Brown 2009, p. 245.

- Brown 2009, p. 252.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 668.

- Goudoever 1986, p. 100.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 669.

- Vasilʹeva, Larisa Nikolaevna (1994). Kremlin wives. Arcade Publishing. p. 159. ISBN 9781559702607.

- Medvedev, Roy (1984). All Stalin's Men. Anchor Press/Doubleday. p. 109. ISBN 0-385-18388-7.

- Shapiro, Henry (29 August 1968). "Rare Historic Memoir May Never See Light". The Daily Colonist (Victoria, Canada). United Press International. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "12 July 1984* (Pb)". wordpress.com. 1 July 2016.

- Goudoever 1986, p. 108.

- Человек, который знал всё. Личное дело наркома Молотова aif.ru. 9 March 2014.

- Anderson, Raymond H. "VYACHESLAV M. MOLOTOV IS DEAD; CLOSE ASSOCIATE OF STALIN WAS 96". The New York Times.

- Zubok & Pleshakov 1996, p. 88.

- Molotov, Vyacheslav; Chuev, Felix; Resis, Albert (1993). Molotov remembers: inside Kremlin politics: conversations with Felix Chuev. I.R. Dee. p. 84. ISBN 1-56663-027-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Zubok & Pleshakov 1996, p. 89.

- Zubok & Pleshakov 1996, pp. 90–91.

- Zubok & Pleshakov 1996, p. 90.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 335.

- Langdon-Davies, John (June 1940). "The Lessons of Finland". Picture Post.

- Montefiore 2005, p. 328.

- Churchill, Winston (1948). The Gathering Storm. 1. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 368–369. ISBN 0-395-41055-X.

- Borejsza, Jerzy W.; Ziemer, Klaus; Hułas, Magdalena (2006). Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes in Europe. Berghahn Books. p. 521. ISBN 1-57181-641-0.

- Kyiv court accuses Stalin leadership of organizing famine, Kyiv Post (13 January 2010)

Further reading

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise & Fall of Communism. Bodley Head.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505000-2. Preview via The New York Times.

- ——. Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization. Oxford University Press.

- van Goudoever, A.P. (1986). The limits of destalinization in the Soviet Union: political rehabilitations in the Soviet Union since Stalin. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7099-2629-4.

- Kotkin, Stephen. 2017. Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929-1941. New York: Random House.

- Martinovich Zubok, Vladislav; Pleshakov, Konstantin (1996). Inside the Kremlin's Cold War: from Stalin to Khrushchev. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-45531-2.

- McCauley, Martin (1997). Who's Who in Russia since 1900. pp 146–47

- Sebag-Montefiore, Simon (2005). Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Vintage Books. ISBN 1-4000-7678-1.

- Service, Robert (2003). History of Modern Russia: From Tsarism to the Twenty-first Century. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-103797-0.

- Watson, Derek (2005). Molotov: A Biography. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333585887.

Primary sources

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vyacheslav Molotov. |

- Works by or about Vyacheslav Molotov at Internet Archive

- Annotated bibliography for Vyacheslav Molotov from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- The Meaning of the Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact Molotov speech to the Supreme Soviet on 31 August 1939

- Reaction to German Invasion of 22 June 1941

- Newspaper clippings about Vyacheslav Molotov in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexey Rykov |

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars 1930–1941 |

Succeeded by Joseph Stalin |

| Preceded by Maxim Litvinov |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1939–1949 1953–1956 |

Succeeded by Andrey Vyshinsky |

| Preceded by Andrey Vyshinsky |

Succeeded by Dmitri Shepilov | |

| Preceded by Vasiliy Pisarev |

Soviet Ambassador to Mongolia 1957–1960 |

Succeeded by Alexei Khvorostukhin |

| Preceded by Leonid Zamiatin |

Soviet Representative to International Atomic Energy Agency 1960–1962 |

Succeeded by Panteleimon Ponomarenko |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by position created (chairman of revkom) |

Secretary of the Communist Party of Donetsk Governorate 1920–1920 |

Succeeded by Taras Kharchenko Andrei Radchenko |

| Preceded by Stanislav Kosior (temporary) |

First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine 1920–1921 |

Succeeded by Feliks Kon (acting) |

| Preceded by Nikolai Uglanov |

Secretary of the Communist Party of Moscow Governorate 1928–1929 |

Succeeded by Karl Bauman |