Waller Plan

The 1839 Austin city plan (commonly known as the Waller Plan) is the original city plan for the development of Austin, Texas, which established the grid plan for what is now downtown Austin. It was commissioned in 1839 by the government of the Republic of Texas and developed by Edwin Waller, a Texian revolutionary and politician who would later become Austin's first mayor.

History

In January 1839 the Congress of the Republic of Texas appointed a committee to select a site for a new planned capital for the republic. Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar instructed the committee to consider a site along the north bank of the Colorado River that he had visited the previous year. The committee was pleased with the site's scenery, resources, and central location within the country, and it approved the site in April, purchasing a parcel of 7,735 acres (3,130 ha) of land that included the village of Waterloo.[1] Shortly before the site selection was publicly announced, President Lamar appointed his friend Edwin Waller to oversee the surveying of the new capital city and to develop a city plan for its layout.[2] Waller had been an early Anglo-American settler in Mexican Texas, fought in the Texas Revolution, and participated in the Convention of 1836 as a delegate from Brazoria, where he held various political offices.[3]

City plan

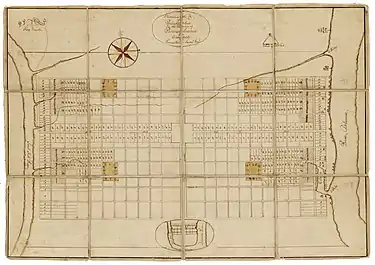

Waller selected a 1-mile (1.6 km) square tract on the north shore of the Colorado, sitting roughly between the mouths of two smaller streams entering the river (now known as Shoal Creek and Waller Creek).[2] Assisted by surveyors L. J. Pilie and Charles Schoolfield, Waller divided the 640-acre (260 ha) tract into a grid plan fourteen city blocks wide,[1] with the blocks separated by broad 80-foot (24 m) streets.[2] Waller organized the grid around an open four-block town square meant for the Texas Capitol, with major avenues intersecting at the Capitol Square, and four smaller public squares in the quarters of the surrounding city. He is thought to have drawn inspiration from Thomas Holme's 1682 city plan of central Philadelphia,[4] though no direct references to the Philadelphia plan from Waller himself are extant.[5]

The central street of the city, Congress Avenue, ran northward from the bank of the river along a natural valley to the Capitol Square hilltop.[6] Another major street, College Avenue (now 12th Street), ran to the Capitol Square from the west and east; both of these avenues were laid 120 feet (37 m) wide. The city limits were marked by Water Avenue (now Cesar Chavez Street) on the south, 100-foot-wide (30 m) North Avenue (now 15th Street), and 200-foot-wide (61 m) West Avenue and East Avenue (now Interstate Highway 35).[2]

Aside from these more prominent avenues, the other streets in the grid were named in one of two ways, depending on their orientation. The north–south streets were named for Texas rivers, arranged in the city to correspond to their positions west-to-east within Texas: Rio Grande Street, Nueces Street, San Antonio Street, Guadalupe Street, Lavaca Street, Colorado Street, Brazos Street, San Jacinto Street, Trinity Street, Neches Street, Red River Street, and Sabine Street.[7] In another parallel with the Holme plan for Philadelphia,[8] the east–west streets were named for various kinds of Texas trees: Live Oak Street, Cypress Street, Cedar Street, Pine Street, Pecan Street, Bois d'Arc Street, Hickory Street, Ash Street, Mulberry Street, Mesquite Street, Peach Street, and Walnut Street.[9]

In addition to the large Capitol Square on a central hilltop, the plan designated four smaller one-block "Public Squares" arranged symmetrically at the corners of a rectangle: the western squares sat between San Antonio and Guadalupe Streets, the eastern two between Trinity and Neches Streets, the southern two between Cedar and Pine Streets, and the northern two between Ash and Mulberry Streets. Though the Waller Plan left these squares unnamed, they were later called Hamilton Square (in the southwest, now known as Republic Square), Bell Square (in the northwest, now Wooldridge Park Square), Brush Square (in the southeast), and Hemphill Square (in the northeast).[10] The plan also designated spaces for a hospital, an academy and university, churches, a courthouse and jail, an armory, and a penitentiary.[5]

With the surveying and grid plan completed, Waller and his associates drew up a plat dividing the city blocks into land lots. The first auction of lots was held on August 1, 1839,[1] under a group of live oak trees in what was to be the city's southwestern public square; these trees have since been known as the "Auction Oaks". The auction raised $182,585 (equivalent to $4,384,000 in 2019), funds used to pay for the construction of government buildings for the new capital city.[11][10]

Legacy

The government offices of the Republic of Texas relocated from Houston and opened in October 1839, operating from temporary buildings, and the Texas Congress convened in November in the first Texas Capitol building, a small wooden structure built at a temporary site at the corner of Colorado and Hickory Streets. The city of Austin was incorporated on December 27, and Waller was elected as the new capital's first mayor on January 13, 1840.[1]

In its first decades Austin grew slowly, in part because of the Texas Archive War of 1842 and uncertainty about the city's future as a capital, and in part because of the disruptions of the American Civil War. It wasn't until the 1870s, with the arrival of the Houston and Texas Central Railway and the economic boom of the post-war Reconstruction era, that Austin expanded significantly beyond the bounds of the 1839 Waller Plan.[1]

In the 1880s the east–west streets originally named for trees were changed to numbered streets (Water Avenue became 1st Street, Live Oak Street became 2nd Street, and so on),[9] but the geographically-inspired river names for the north–south streets remain to the present day.[7] The Texas Capitol Complex has expanded beyond its original four-block square, but the Capitol building retains the commanding position on a hilltop overlooking the central city envisioned by Waller. Hemphill Square, the northeastern public square designated in the Waller Plan, has been built over, but Brush Square, Republic Square, and Wooldridge Park remain public urban green spaces.[10] The plan assigned a number from 1 to 179 to each city block,[5] and these block numbers are still used to refer to sections of downtown in planning documents and public discussion.[12]

Austin's next comprehensive city plan was drawn up in 1928 by the Dallas-based consulting firm Koch & Fowler, and it praised the Waller Plan's foresight in providing a preeminent space for the Capitol and in laying such wide streets in the central city, though it also criticized the grid plan for ignoring the local topography, which gave some downtown streets awkwardly steep grades.[13]:4 It also noted the good condition of the three surviving park squares from the Waller Plan and their value to the city as "beauty spots and breathing spaces".[13]:25–26 Today, the street map of downtown Austin retains much of the design laid down in the 1839 Waller Plan.[7]

References

- Humphrey, David C. "Austin, TX (Travis County)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "West Sixth Street Bridge at Shoal Creek" (PDF). National Park Service. June 24, 2014. p. 7. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Spurlin, Charles D. "Waller, Edwin Leonard (1800–1881)". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "East Austin MRA". National Park Service. September 17, 1985. p. 13. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Barnes, Michael (August 29, 2015). "The puzzlement of Austin's original city plan". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Congress Avenue Historic District" (PDF). Texas Historical Commission. August 11, 1978. p. 2. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Austin Streets". Austin History Center. Austin Public Library. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Cuff, David J; Young, William J.; Muller, Edward K.; Zelinsky, Wilbur; Abler, Ronald F., eds. (1989). The Atlas of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-87722-618-5.

- Hamda, Nadia (August 24, 2017). "Where Did First Street Go, And Why Isn't South First Parallel To Other Numbered Streets?". KUT. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Bueche, Shelley (July 15, 2019). "This tiny downtown Austin park had a mighty impact on the city's history". CultureMap Austin. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Auction Oaks". Famous Trees of Texas. Texas A&M Forest Service. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- "Travis County: Block 126 Redevelopment" (PDF). Urban Land Institute. September 20, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Koch & Fowler (1928). "A City Plan for Austin, Texas" (PDF). City of Austin. Retrieved December 30, 2020.