Walter Tull

Walter Daniel John Tull (28 April 1888 – 25 March 1918) was an English professional footballer and British Army officer of Afro-Caribbean descent. He played as an inside forward and half back for Clapton, Tottenham Hotspur and Northampton Town and was the third person of mixed heritage to play in the top division of the Football League after Arthur Wharton and Willie Clarke. He was also the first black player to be signed for Rangers F.C. in 1917 while stationed in Scotland.

| |||

| Personal information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Walter Daniel John Tull[1] | ||

| Date of birth | 28 April 1888 | ||

| Place of birth | Folkestone, England | ||

| Date of death | 25 March 1918 (aged 29)[1] | ||

| Place of death | near Favreuil, Pas-de-Calais, France | ||

| Position(s) | Half back | ||

| Senior career* | |||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) |

| 1908–1909 | Clapton | ||

| 1909–1911 | Tottenham Hotspur | 10 | (2) |

| 1911–1914 | Northampton Town | 105 | (9) |

| * Senior club appearances and goals counted for the domestic league only | |||

During the First World War, Tull served in the Middlesex Regiment, including in the two Footballers' Battalions. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 30 May 1917 and killed in action on 25 March 1918.

Early life

Tull was born in Folkestone, Kent, the son of Barbadian carpenter Daniel Tull and Kent-born Alice Elizabeth Palmer. His paternal grandfather was a slave in Barbados.[2] His maternal English grandmother was from Kent. He began his education at North Board School, now Mundella Primary School, Folkestone.[3]

In 1895, when Tull was seven, his mother died of cancer. A year later his father married Alice's cousin, Clara Palmer. She gave birth to a daughter Miriam, on 11 September 1897. Three months later, Daniel died from heart disease. The stepmother was unable to cope with five children so the resident minister of Folkestone's Grace Hill Wesleyan Chapel, recommended that the two boys of school age, Walter and Edward, should be sent to an orphanage.[4] From the age of 9, Tull was brought up in the (Methodist) Children's Home and Orphanage (now known as Action for Children) in Bethnal Green, London. His brother was adopted by the Warnock family of Glasgow, becoming Edward Tull-Warnock; he qualified as a dentist, the first mixed-heritage person to practise this profession in the United Kingdom.[5]

Football career

His professional football career began after he was spotted playing for top amateur club, Clapton F.C.. He had signed for Clapton in October 1908, reportedly never playing in a losing side. By the end of the season he had won winners' medals in the FA Amateur Cup, London County Amateur Cup and London Senior Cup. In March 1909 the Football Star called him "the catch of the season".[6][7][8] At Clapton, he played alongside Clyde Purnell and Charlie Rance.

At the age of 21, Tull signed for Football League First Division team, Tottenham Hotspur, in the summer of 1909, after a close-season tour of Argentina and Uruguay, making him the first mixed-heritage professional footballer to play in Latin America. Tull made his debut for Tottenham in September 1909 at inside forward against Sunderland and his home Football League debut against FA Cup-holders, Manchester United, in front of over 30,000.[9] His excellent form in this opening part of the season promised a great future. Tull made only 10 first-team appearances, scoring twice, before he was dropped to the reserves.[10] This may have been due to the racial abuse he received from opposing fans, particularly at Bristol City, whose supporters used language "lower than Billingsgate",[lower-alpha 1] according to a report at the time in the Football Star newspaper.[12] The match report of the game away to Bristol City in October 1909 by Football Star reporter, "DD", was headlined "Football and the Colour Prejudice", possibly the first time racial abuse was headlined in a football report. "DD" emphasised how Tull remained professional and composed despite the intense provocation; "He is Hotspur's most brainy forward ... so clean in mind and method as to be a model for all white men who play football ... Tull was the best forward on the field." However, soon after, Tull was dropped from the first team and found it difficult to get a sustained run back in the side.

Further appearances in the first team (20 in total with four goals) were recorded before Tull's contract was bought by Southern Football League club Northampton Town on 17 October 1911 for a "substantial fee" plus Charlie Brittain joining Tottenham Hotspur in return.[13] Tull made his debut four days later against Watford, and made 111 first-team appearances (105 in the League), scoring nine goals for the club.[14] The manager Herbert Chapman – also a Methodist – was a former Spurs player and had played as a young man with Arthur Wharton at Stalybridge Rovers; he went on to manage both Huddersfield Town and Arsenal to FA Cup wins and League championships.

In 1940, it was reported in an article in the Glasgow Evening Times about Tull being the first "coloured" infantry officer in the British Army, that he had signed to play for Rangers F.C. after the war. Rangers have confirmed that Tull signed for them in February 1917,[15] while an officer cadet in Scotland at Gailes, Ayrshire.

First World War

After the First World War broke out in August 1914, Tull became the first Northampton Town player to enlist in the British Army, in December of that year. Tull served in the two Football Battalions of the Duke of Cambridge's Own (Middlesex) Regiment – the 17th and 23rd – and also in the 5th Battalion. He rose to the rank of lance sergeant and fought in the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

When Tull was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 30 May 1917,[16] he became one of the first mixed-heritage infantry officers in a regular British Army regiment,[lower-alpha 2] when the 1914 Manual of Military Law excluded soldiers that were not "natural born or naturalised British subjects of pure European descent" from becoming commissioned officers in the Special Reserve.

With the 23rd Battalion, Tull fought on the Italian Front from 30 November 1917 to early March 1918. He was praised for his "gallantry and coolness" by Major-General Sydney Lawford, General Officer Commanding 41st Division, having led 26 men on a night-raiding party, crossing the fast-flowing rapids of the Piave River into enemy territory and returning them unharmed, and in a letter of condolence to his family. The commanding officer of the 23rd Battalion, Major Poole and his colleague 2Lt Pickard both said that Tull had been put forward for a Military Cross. Pickard wrote "he had been recommended for the Military Cross, and certainly earned it."[7] However, the Ministry of Defence has no record of any recommendation[19] but many records were lost in a 1940 fire. It would have been against army regulations for serving officers to inform an officer's next of kin that their relative had been recommended for, and refused, an honour; it was a court-martial offence.[7]

Tull and the 23rd Battalion returned to northern France on 8 March 1918. He was killed in action near the village of Favreuil in the Pas-de-Calais on 25 March during the First Battle of Bapaume, the early stages of the German Army's Spring Offensive.[20] His body was never recovered, despite the efforts of, among others, Private Tom Billingham, a former goalkeeper for Leicester Fosse to return him to the British position while under fire.[21]

Legacy

In the history of mixed-heritage footballers in Britain, Tull may be mentioned alongside Robert Walker of Third Lanark, Andrew Watson, an amateur who is credited as the earliest black international football player winning his first cap for Scotland in 1881, Arthur Wharton, a goalkeeper for several clubs including Darlington and became the first mixed-heritage professional in 1889, John Walker of Hearts and Lincoln who died aged 22, the Anglo-Indian Cother brothers, Edwin and John began their careers at Watford in 1898[22] and W. G. Clarke who played for Aston Villa and Bradford City in the Edwardian era.

From around 2006, campaigners including the then Northampton South MP, Brian Binley, and Phil Vasili, who has researched Tull since the early 1990s, called for a statue to be erected in his honour at Dover and for him to be posthumously awarded the Military Cross.[12][23] However, as the Military Cross was not authorised to be awarded posthumously until 1979, and the change did not include any provision for retrospective awards, this would not be possible without a change in the rules. The campaigners felt this would be justified given that the army broke the rules in allowing Tull a commission at a time when the army was desperately short of officers. If he had been recommended for a Military Cross, his status as an officer of non-European descent might have meant to award him the honour would validate his status, leading to more mixed-heritage officers being commissioned.[24][lower-alpha 3]

Memorials

Tull is commemorated on Bay 7 of the Arras Memorial[25] which commemorates 34,785 soldiers who have no known grave, who died in the Arras sector.

His name was added to his parents' gravestone in Cheriton Road Cemetery, Folkestone. His older brother William, of the Royal Engineers, died in 1920, aged 37, and is buried in the cemetery with a CWGC headstone[26] so his death was recognised as a result of his war service.

Tull's name appeared on the war memorial at North Board School, Folkestone, unveiled on 29 April 1921.[27] He is named on the Folkestone War Memorial, at the top of the Road of Remembrance in Folkestone, and in Dover his name is on the town war memorial outside Maison Dieu House, and on the parish memorial at River.[28]

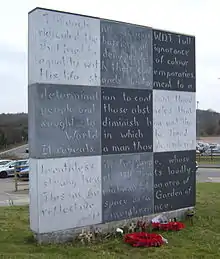

On 11 July 1999, Northampton Town F.C. unveiled a memorial wall to Tull in a garden of remembrance at Sixfields Stadium.[29] The text, written by Tull's biographer, Phil Vasili, reads:

Through his actions, W. D. J. Tull ridiculed the barriers of ignorance that tried to deny people of colour equality with their contemporaries. His life stands testament to a determination to confront those people and those obstacles that sought to diminish him and the world in which he lived. It reveals a man, though rendered breathless in his prime, whose strong heart still beats loudly.[30]

A road behind the North Stand (The Dave Bowen Stand) at Sixfields Stadium is named Walter Tull Way, and a public house, adjacent to the stadium, bears his name.[31]

On 28 July 2004, Tottenham Hotspur and Rangers contested the "Walter Tull Memorial Cup". Rangers won the Cup, defeating Spurs 2–0 with goals from Dado Pršo and Nacho Novo.[32]

In 2010, a planning application to erect a bronze memorial statue of Tull in Geraldine Mary Harmsworth Park close to the Imperial War Museum in London, was refused by Southwark London Borough Council.[33]

The Royal Mint included a £5 coin honouring Tull in the introductory First World War six-coin set, released in 2014.[34]

On 21 October 2014, a blue plaque was unveiled at 77 Northumberland Park, London N17, on the site of the house where Tull lived before the war, close to the White Hart Lane ground. The plaque was provided by the Nubian Jak Community Trust and was unveiled by former Spurs striker Garth Crooks who described Tull as an "amazing man," whose recognition had been "a long time coming".[35]

On 4 July 2017, five statues including one of Tull were unveiled in the courtyard of Northampton Guildhall. The bronze installations were commissioned by Northampton Borough Council from sculptor Richard Austin.[36]

On 25 March 2018, to commemorate the centenary of his death, Rushden & District History Society unveiled a blue plaque at 26 Queen Street, Rushden where he lodged while playing at Northampton Town.[37]

In September 2018, to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War, Royal Mail produced a set of stamps, one of which features Tull.[38]

On Remembrance Sunday 2018, the people of Ayr, Scotland, came together to etch a large sand portrait of Tull into the town's beach as part of 'Pages of the Sea', a nationwide public art project curated by Oscar-winning filmmaker Danny Boyle.[39]

In October 2020, as part of Black History Month, the Royal Mail have painted a postbox black in Glasgow to honour Tull.[40]

Media

Respect!, an account of Tull's life, written for young people by Michaela Morgan, was published by Barrington Stoke in 2005. The book was shortlisted in the Birmingham Libraries young readers' book festival May 2008.[41]

A fictional work, Fields of Glory: The Diary of Walter Tull, by Maureen Lewis, Jillian Powell and Bernice Barry, was published by Longman in 2005.[42] (Please note: this is a work of fiction; there is no surviving diary written by Tull.)

Two films, focusing on teaching about Tull, were made for Teachers TV and launched in May 2008.[43][44]

Walter's War, a drama about the life of Tull, starring O. T. Fagbenle and written by Kwame Kwei-Armah, was made by UK channel BBC Four and first screened on 9 November 2008 as part of the BBC's Ninety Years of Remembrance season.[45] The drama was aired alongside Forgotten Hero, a documentary about Tull.

A biography by Phil Vasili, titled Walter Tull, 1888–1918, Officer, Footballer was published by Raw Press, 2010. A revised edition was published in 2018 by London League Publications.[46]

A book for young readers, Walter Tull: Footballer, Soldier, Hero, written by Dan Lyndon, was published by Collins Educational in January 2011.[47]

A Medal for Leroy (2012)[48] by Michael Morpurgo is inspired by the life of Tull.[49]

The Octagon Theatre, Bolton staged Vasili's play Tull, 21 February to 16 March 2013. Working with local young people Tottenham Theatre Group produced a version at the Bernie Grant Centre in Tottenham in 2014.

In 2014, Gazebo Theatre, based in Bilston Town Hall, toured a play about the life of Tull, entitled The Hallowed Turf. It was presented in Wolverhampton on 3 October to launch the city's Black History Month.[50]

In 2016 Off The Records films made an animated film about Tull's life, voiced by actor Liam Gerrard. The film was nominated for a children's BAFTA.[51][52]

Notes

- The raucous cries of the fish vendors at Billingsgate Fish Market gave rise to "Billingsgate" as a synonym for profanity or offensive language.[11]

- Nathaniel Wells, the son of a white plantation owner and a black slave, received a Yeomanry commission in 1818;[17] Allan Noel Minns, DSO, MC, was commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps in September 1914, Euan Lucie-Smith (killed in action 25 April 1915) was commissioned in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in November 1914, George Bemand was commissioned in the Royal Field Artillery in 1915, although on his attestation form he categorises himself as being of "pure European descent"; and David Clemetson was commissioned in the territorial Pembroke Yeomanry in October 1915.[18]

- But Allan Noel Minns, also a natural born British subject of Afro-Caribbean descent, was awarded both DSO and MC

References

- "Casualty". www.cwgc.org. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Dan Lyndon, Walter Tull: Footballer, Soldier, Hero, London: Collins Educational, 2011.

- "The Extraordinary Life of Walter Tull". BBC. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- "Walter Tull". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Vasili, Phil (September 2004). "Tull, Walter Daniel John (1888–1918)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/62348. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Phil Vasili 'Tull, a forgotten black history' Race and Class, Vol.38, October–December 1996, Number 2.

- Phil Vasili 'Walter Tull, 1888–1918, Officer, Footballer' (London, Raw Press 2009)

- Rod Wickens 'From Claret to Khaki' (Liverpool, 2003)

- Wynn, Stephen (30 January 2018). Against all the Odds:Walter Tull the Black Lieutenant. ISBN 9781526704078. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Topspurs A-Z of players. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "billingsgate - Word of the Day | Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Sapsted, David (13 June 2008). "Call to honour black Army hero". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- Garland, Jon. "Racism and Anti-Racism in Football". Palgrave Macmillan. p. 32. Retrieved 10 May 2001.

- Grande, Frank (1991). Northampton Town F.C.: The Official Centenary History. Yore Publications. p. 156. ISBN 978-1874427674.

- "Walter Tull: Rangers' first black player appears on Glasgow postbox". Sky Sports. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- "No. 30134". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 June 1917. p. 5970.

- W. H. Wyndham-Quin (2005) [1898]. The Yeomanry Cavalry of Gloucestershire and Monmouth. Golden Valley. ISBN 0-9542578-5-5.

- The officer who refused to lie about being black, BBC News Magazine, 17 April 2015

- Alleyne, Richard. "Britain's first black officer should be honoured". Telegraph. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Wyrall, Edward (1926). The Die-hards in the Great War; vol. II. London: Harrison. p. 203.

- "Walter Tull: The incredible story of a football pioneer and war hero". BBC Sport. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "The Cother brothers". Our Watford History: Telling the stories of a diverse town. 17 August 2006. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Medal campaign for black pioneer", BBC News, 23 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Ed Aarons. "Walter Tull: why the black footballing pioneer was denied a Military Cross | Football". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Casualty details—Tull, Walter Daniel John". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- "Casualty details—Tull, W S P". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "North Board School, Folkestone". Doverwarmemorialproject. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Walter Tull". Doverwarmemorialproject. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "In Memoriam", Northampton Town FC website.

- "2nd. Lieutenant W. D. J. Tull - Wall Tablets - War Memorials Register - Imperial War Museums". www.ukniwm.org.uk. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Walter Tull". Flaming Grills Pubs. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- "Rangers see off sorry Spurs". BBC Sport. 28 July 2004.

- "Details of planning application – 10/AP/1361". London Borough of Southwark. 21 May 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "British Army's first black officer Walter Tull remembered on coins". 3 September 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Centenary news Retrieved 30 April 2015

- Alistair Ulke (3 July 2017). "Northampton's history makers cast in bronze for new £44,000 borough art installation". Northampton Chronicle & Echo. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "Rushden Research Blue Plaques". Rushden Research. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Walter Tull in First World War stamp collection". Tottenham Hotspur F. C. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- Kelly, Guy (11 November 2018). "Pages of the Sea: Nationwide project to remembers soldiers who fell during Great War". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Walter Tull:Rangers' first black player appears on Glasgow postbox". Sky Sports. 2 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- Birmingham libraries book festival 2008, 30 July 2008.

- Lewis, Maureen; Jillian Powell; Bernice Barry (2005). Fields of Glory: The Diary of Walter Tull. Longman. ISBN 0-582-85155-6.

- "Walter Tull – Race, Football and Black Britain 1909". Teachers' TV. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- "Walter Tull – the Pupils' Perspective". Teachers' TV. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- Riley, Alrick (9 November 2008), Walter's War, O.-T. Fagbenle, Paul Westwood, Zac Fox, retrieved 23 March 2018

- Vasili, Phil (2018). Walter Tull 1888 to 1918: Footballer and Officer (2nd ed.). London League Publications. ISBN 978-1909885172.

- Lydon, Dan (2011). Walter Tull:Footballer, Soldier, Hero. Collins Educational. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-00-733637-1.

- Morpurgo, Michael (September 2012). A Medal For Leroy. HarperCollins childrens books. ISBN 978-0007339686.

- Morpurgo, Michael (24 September 2012). "Michael Morpurgo: Britain's first black Army officer inspired my new novel". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "Gazebo Theatre". Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Walter Tull: Britain's Black Officer". IMDB. 1 May 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "2016 Children's Learning - Secondary - BAFTA Awards". awards.bafta.org. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

Further reading

- Baker, Chris. "Walter Daniel Tull and recommendation for the Military Cross" The Long, Long Trail, 21 June 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Daniel, Peter. "Crossing the white line: the Walter Tull story" (PDF). City of Westminster Archives Centre. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Kuper, Simon. "Political Football: Walter Tull", Channel 4 News, 4 September 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- McMullen, Iain. "Walter Tull", Football and the First World War.Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Simkin, John. "Walter Tull", Spartacus Educational.Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Stephenson-Knight, Marilyn. "First Black Army Officer, Footballer, and Great War Hero", The Dover War Memorial Project. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Turner, Lyndsey. "The lesson: Walter Tull", The Guardian, 25 March 1998. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Vasili, Phil (2000). Colouring Over the White Line: History of Black Footballers in Britain. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-296-2.

- Teaching material about Walter Tull, produced for Northamptonshire Black History Association, www.blackhistory4schools.com. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "The extraordinary life of Walter Tull", BBC London, 13 November 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

External links

- WalterTull.org

- Walter Daniel John Tull on Lives of the First World War

- For records relating to Tull in The National Archives, see Your Archives

- Tull's application for a temporary commission at The National Archives