Wesleyan theology

Wesleyan theology, otherwise known as Wesleyan–Arminian theology, or Methodist theology, is a theological tradition in Protestant Christianity that emphasizes the "methods" of the 18th-century evangelical reformer brothers John Wesley and Charles Wesley. More broadly it refers to the theological system inferred from the various sermons, theological treatises, letters, journals, diaries, hymns, and other spiritual writings of the Wesleys and their contemporary coadjutors such as John William Fletcher.

| Part of a series on |

| Methodism |

|---|

|

|

|

Wesleyan–Arminian theology, manifest today in Methodism (inclusive of the Holiness movement), is named for its founders, the Wesleys, as well as for Jacobus Arminius, since it is a subset of Arminian theology. In 1736, these two brothers traveled to the Georgia colony in America as missionaries for the Church of England; they left rather disheartened at what they saw. Both of them subsequently had "religious experiences", especially John in 1738, being greatly influenced by the Moravian Christians. They began to organize a renewal movement within the Church of England to focus on personal faith and holiness. John Wesley took Protestant churches to task over the nature of sanctification, the process by which a believer is conformed to the image of Christ, emphasizing New Testament teachings regarding the work of God and the believer in sanctification. The movement did well within the Church of England in Britain, but when the movement crossed the ocean into America, it took on a form of its own, finally being established as the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1784. The Methodist churches are similar to Anglicanism (in Church government and liturgical practices), yet have added a strong emphasis on personal faith and personal experience, especially on the new birth and entire sanctification.

At its heart, the theology of John Wesley stressed the life of Christian holiness: to love God with all one’s heart, mind, soul and strength, and to love one's neighbour as oneself. Wesley’s teaching also stressed experiential religion and moral responsibility.[1]

Background

The doctrine of Wesleyan–Arminianism was founded as an attempt to explain Christianity in a manner unlike the teachings of Calvinism. Arminianism is a theological study conducted by Jacobus Arminius, from the Netherlands, in opposition to Calvinist orthodoxy on the basis of free will.[2] After the death of Arminius the followers, led by Simon Episcopius, presented a document concerning the Arminian beliefs to the Netherlands. This document is known today as the Five Articles of Remonstrance.[2] Wesleyan Arminianism, on the other hand, was founded upon the theological teachings of John Wesley, an English evangelist, and the beliefs of this dogma are derived from his many publications, including his sermons, journal, abridgements of theological, devotional, and historical Christian works, and a variety of tracts and treatises on theological subjects. Subsequently, the two theories have joined into one set of values for the contemporary church; yet, when examined separately, their unique details can be discovered, as well as their similarities in ideals.[2]

In the early 1770s, John Wesley, aided by the theological writings of John William Fletcher, emphasized Arminian doctrines in his controversy with the Calvinistic wing of the evangelicals in England. Then, in 1778, he founded a theological journal which he titled the Arminian Magazine. This period, during the Calvinist–Arminian debate, was influential in forming a lasting link between Arminian and Wesleyan theology.[3]

Wesley is remembered for visiting the Moravians of both Georgia and Germany and examining their beliefs, then founding the Methodist movement, the precursor to the later variety of Methodist denominations. Wesley's desire was not to form a new sect, but rather to reform the nation and spread scriptural holiness as truth. However, the creation of Wesleyan-Arminianism has today developed into a popular standard for many contemporary churches.

In the broad sense of the term, the Wesleyan tradition identifies the theological impetus for those movements and denominations who trace their roots to a theological tradition finding its initial focus in Wesley. Although its primary legacy remains within the various Methodist denominations (the Wesleyan Methodist, the Free Methodist, the African Methodist Episcopal, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion, the Christian Methodist Episcopal, the United Methodist, the Free Methodist Church of North America, The Church of the Nazarene, The Wesleyan Church, and others), the Wesleyan tradition has been refined and reinterpreted as catalyst for other movements and denominations as well, e.g., Charles Finney and the holiness movement; William J. Seymour and the Pentecostal movement; Phineas Bresee and the Church of the Nazarene.

Wesleyan distinctives

New Birth

In Wesleyan theology, the "new birth is necessary for salvation because it marks the move toward holiness. That comes with faith."[4] Wesley held that the New Birth "is that great change which God works in the soul when he brings it into life, when he raises it from the death of sin to the life of righteousness" (Works, vol. 2, pp. 193–194).[4] In the life of a Christian, the new birth is considered the first work of grace.[5] The Articles of Religion, in Article XVII—Of Baptism, state that baptism is a "sign of regeneration or the new birth."[6] The Methodist Visitor in describing this doctrine, admonishes individuals: "'Ye must be born again.' Yield to God that He may perform this work in and for you. Admit Him to your heart. 'Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved.'"[7][8]

Salvation

The Wesleyan tradition seeks to establish justification by faith as the gateway to sanctification or "scriptural holiness." Wesley insisted that imputed righteousness must become imparted righteousness. He believed that one could progress in love until love became devoid of self-interest at the moment of entire sanctification.

With regard to good works, A Catechism on the Christian Religion: The Doctrines of Christianity with Special Emphasis on Wesleyan Concepts teaches:[9]

...after a man is saved and has genuine faith, his works are important if he is to keep justified.

146) James 2:20–22, "But wilt thou known, O vain main, that faith without (apart from) works is dead? Was not Abraham our father justified by works, when he had offered Isaac his son upon the altar? Seest thou faith wrought with works, and by works was faith made perfect?[9]

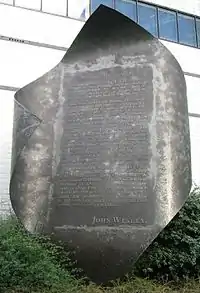

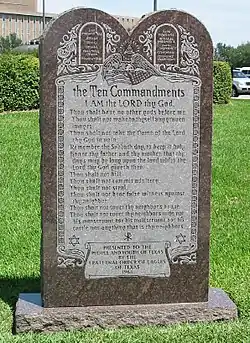

The Methodist Churches affirm the doctrine of justification by faith, but in Wesleyan theology, justification refers to "pardon, the forgiveness of sins", rather than "being made actually just and righteous", which Methodists believe is accomplished through sanctification.[10][11] John Wesley taught that the keeping of the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments,[12] as well as engaging in the works of piety and the works of mercy, were "indispensable for our sanctification".[13]

Wesley understood faith as a necessity for salvation, even calling it “the sole condition” of salvation, in the sense that it led to justification, the beginning point of salvation. At the same time, “as glorious and honorable as [faith] is, it is not the end of the commandment. God hath given this honor to love alone” (“The Law Established through Faith II,” §II.1). Faith is “an unspeakable blessing” because “it leads to that end, the establishing anew the law of love in our hearts” (“The Law Established through Faith II,” §II.6) This end, the law of love ruling in our hearts, is the fullest expression of salvation; it is Christian perfection. —Amy Wagner[14]

Methodist soteriology emphasize the importance of the pursuit of holiness in salvation.[15] Thus, for Methodists, "true faith...cannot subsist without works".[13] Bishop Scott J. Jones in United Methodist Doctrine writes that in Methodist theology:[16]

Faith is necessary to salvation unconditionally. Good works are necessary only conditionally, that is if there is time and opportunity. The thief on the cross in Luke 23:39–43 is Wesley's example of this. He believed in Christ and was told, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise." This would be impossible if the good works that are the fruit of genuine repentance and faith were unconditionally necessary for salvation. The man was dying and lacked time; his movements were confined and he lacked opportunity. In his case, faith alone was necessary. However, for the vast majority of human beings good works are necessary for continuance in faith because those persons have both the time and opportunity for them.[16]

Bishop Jones concludes that "United Methodist doctrine thus understands true, saving faith to be the kind that, give time and opportunity, will result in good works. Any supposed faith that does not in fact lead to such behaviors is not genuine, saving faith."[16] Methodist evangelist Phoebe Palmer stated that "justification would have ended with me had I refused to be holy."[17] While "faith is essential for a meaningful relationship with God, our relationship with God also takes shape through our care for people, the community, and creation itself."[18] Methodism, inclusive of the holiness movement, thus teaches that "justification [is made] conditional on obedience and progress in sanctification"[17] emphasizing "a deep reliance upon Christ not only in coming to faith, but in remaining in the faith."[19]

Richard P. Bucher, contrasts this position with the Lutheran one, discussing an analogy put forth by John Wesley:[20]

Whereas in Lutheran theology the central doctrine and focus of all our worship and life is justification by grace through faith, for Methodists the central focus has always been holy living and the striving for perfection. Wesley gave the analogy of a house. He said repentance is the porch. Faith is the door. But holy living is the house itself. Holy living is true religion. “Salvation is like a house. To get into the house you first have to get on the porch (repentance) and then you have to go through the door (faith). But the house itself—one’s relationship with God—is holiness, holy living” (Joyner, paraphrasing Wesley, 3).[20]

With regard to the fate of the unlearned, Willard Francis Mallalieu, a Methodist bishop, wrote in Some Things That Methodism Stands For:[21]

Starting on the assumption that salvation was possible for every redeemed soul, and that all souls are redeemed, it has held fast to the fundamental doctrine that repentance towards God and faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ are the divinely-ordained conditions upon which all complying therewith may be saved, who are intelligent enough to be morally responsible, and have heard the glad tidings of salvation. At the same time Methodism has insisted that all children who are not willing transgressors, and all irresponsible persons, are saved by the grace of God manifest in the atoning work of Christ; and, further, that all in every nation, who fear God and work righteousness, are accepted of him, through the Christ that died for them, though they have not heard of him. This view of the atonement has been held and defended by Methodist theologians from the very first. And it may be said with ever-increasing emphasis that it commends itself to all sensible and unprejudiced thinkers, for this, that it is rational and Scriptural, and at the same time honorable to God and gracious and merciful to man.[21]

Atonement

Methodism falls squarely in the tradition of substitutionary atonement, though it is linked with Christus Victor and moral influence theories.[22] John Wesley, reflecting on Colossians 1:14, connects penal substitution with victory over Satan in his Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament: "the voluntary passion of our Lord appeased the Father's wrath, obtained pardon and acceptance for us, and consequently, dissolved the dominion and power which Satan had over us through our sins."[22] In elucidating 1 John 3:8, Wesley says that Christ manifesting Himself in the hearts of humans destroys the work of Satan, thus making Christus Victor imagery "one part of the framework of substitutionary atonement."[22] The Methodist divine Charles Wesley's hymns "Sinners, Turn, Why Will You Die" and "And Can It be That I Should Gain" concurrently demonstrate that Christ's sacrifice is the example of supreme love, while also convicting the Christian believer of his/her sins, thus using the moral influence theory within the structure of penal substitution in accordance with the Augustinian theology of illumination.[22] Wesleyan theology also emphasizes a participatory nature in atonement, in which the Methodist believer spiritually dies with Christ and He dies for humanity; this is reflected in the words of the following Methodist hymn (122):[22]

"Vouchsafe us eyes of faith to see

The Man transfixed on Calvary,

To know thee, who thou art—

The one eternal God and true;

And let the sight affect, subdue,

And break my stubborn heart...

The unbelieving veil remove,

And by thy manifested love,

And by thy sprinkled blood,

Destroy the love of sin in me,

And get thyself the victory,

And bring me back to God...

Now let thy dying love constrain

My soul to love its God again,

Its God to glorify;

And lo! I come thy cross to share,

Echo thy sacrificial prayer,And with my Saviour die."[22]

The Christian believer, in Methodist theology, mystically draws himself/herself into the scene of the crucifixion in order to experience the power of salvation that it possesses.[22] In the Eucharist, the Methodist especially experiences the participatory nature of substitutionary atonement as "the sacrament sets before our eyes Christ's death and suffering whereby we are transported into an experience of the crucifixion."[22]

Assurance

John Wesley believed that all Christians have a faith which implies an assurance of God's forgiving love, and that one would feel that assurance, or the "witness of the Spirit". This understanding is grounded in Paul's affirmation, "...ye have received the Spirit of adoption, whereby we cry Abba, Father. The same Spirit beareth witness with our spirits, that we are the children of God..." (Romans 8:15–16, Wesley's translation). This experience was mirrored for Wesley in his Aldersgate experience wherein he "knew" he was loved by God and that his sins were forgiven.

- "I felt my heart strangely warmed. I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation, and an assurance was given me that He had taken my sin, even mine." — from Wesley's Journal[24]

Conditional preservation of the saints

John Wesley was an outspoken defender of the doctrine of conditional preservation of the saints, or commonly "conditional security". In 1751, Wesley defended his position in a work titled, "Serious Thoughts Upon the Perseverance of the Saints." In it he argued that a believer remains in a saving relationship with God if he "continue in faith" or "endureth in faith unto the end."[25] Wesley affirmed that a child of God, "while he continues a true believer, cannot go to hell."[26] However, if he makes a "shipwreck of the faith, then a man that believes now may be an unbeliever some time hence" and become "a child of the devil."[26] He then adds, "God is the Father of them that believe, so long as they believe. But the devil is the father of them that believe not, whether they did once believe or no."[27]

Like his Arminian predecessors, Wesley was convinced from the testimony of the Scriptures that a true believer may abandon faith and the way of righteousness and "fall from God as to perish everlastingly."[27]

Christian perfection

Wesleyan theology teaches that there were two distinct phases in the Christian experience.[29] In the first work of grace, the new birth, the believer received forgiveness and became a Christian.[5] During the second work of grace, entire sanctification, the believer was purified and made holy.[5] Wesley taught both that sanctification could be an instantaneous experience,[30] and that it could be a gradual process.[31][32]

Covenant theology

Methodism maintains the superstructure of classical covenant theology, but being Arminian in soteriology, it discards the "predestinarian template of Reformed theology that was part and parcel of its historical development."[33] The main difference between Wesleyan covenant theology and classical covenant theology is as follows:

The point of divergence is Wesley’s conviction that not only is the inauguration of the covenant of grace coincidental with the fall, but so is the termination of the covenant of works. This conviction is of supreme importance for Wesley in facilitating an Arminian adaptation of covenant theology—first, by reconfiguring the reach of the covenant of grace; and second, by disallowing any notion that there is a reinvigoration of the covenant of works beyond the fall.

As such, in the traditional Wesleyan view, only Adam and Eve were under the covenant of works, while on the other hand, all of their progeny are under the covenant of grace.[33] With Mosaic Law belonging to the covenant of grace, all of humanity is brought "within the reach of the provisions of that covenant."[33] This belief is reflected in John Wesley's sermon Righteousness of Faith:[33] "The Apostle does not here oppose the covenant given by Moses, to the covenant given by Christ. ... But it is the covenant of grace, which God, through Christ, hath established with men in all ages".[34] The covenant of grace was therefore administered through "promises, prophecies, sacrifices, and at last by circumcision" during the patriarchal ages and through "the paschal lamb, the scape goat, [and] the priesthood of Aaron" under Mosaic Law.[35] Under the Gospel, the covenant of grace is mediated through the greater sacraments, baptism and the Lord's Supper.[35]

Ecclesiology

.jpg.webp)

Methodists affirm belief in "the one true Church, Apostolic and Universal", viewing their Churches as constituting a "privileged branch of this true church".[37][38] With regard to the position of Methodism within Christendom, the founder of the movement "John Wesley once noted that what God had achieved in the development of Methodism was no mere human endeavor but the work of God. As such it would be preserved by God so long as history remained."[39] Calling it "the grand depositum" of the Methodist faith, Wesley specifically taught that the propagation of the doctrine of entire sanctification was the reason that God raised up the Methodists in the world.[40][36]

Four sources of theological authority

The Wesleyan tradition's defense has normally exercised four sources of authority: Scripture (the Bible), correlated with reason, tradition, and experience. The United Methodist Church, asserts that "Wesley believed that the living core of the Christian faith was revealed in Scripture, illumined by tradition, vivified in personal experience, and confirmed by reason. Scripture [however] is primary, revealing the Word of God 'so far as it is necessary for our salvation.'"[41]

Four Last Things

With respect to the four last things, Wesleyan theology affirms the belief in Hades, "the intermediate state of souls between death and the general resurrection," which is divided into Paradise (for the righteous) and Gehenna (for the wicked).[42][43] After the general judgment, Hades will be abolished.[43] John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, "made a distinction between hell (the receptacle of the damned) and Hades (the receptacle of all separate spirits), and also between paradise (the antechamber of heaven) and heaven itself."[44][45] The dead will remain in Hades "until the Day of Judgment when we will all be bodily resurrected and stand before Christ as our Judge. After the Judgment, the Righteous will go to their eternal reward in Heaven and the Accursed will depart to Hell (see Matthew 25)."[46]

Wesley stated that: "I believe it to be a duty to observe, to pray for the Faithful Departed".[47] He "taught the propriety of Praying for the Dead, practised it himself, provided Forms that others might."[48] In a joint statement with the Catholic Church in England and Wales, the Methodist Church of Great Britain affirmed that "Methodists who pray for the dead thereby commend them to the continuing mercy of God."[49]

Holy Baptism

.jpg.webp)

The Methodist Articles of Religion, with regard to baptism, teach:[50]

Baptism is not only a sign of profession and mark of difference whereby Christians are distinguished from others that are not baptized; but it is also a sign of regeneration or the new birth. The Baptism of young children is to be retained in the Church.[50]

While baptism imparts regenerating grace, its permanence is contingent upon repentance and a personal commitment to Jesus Christ.[51] Wesleyan theology holds that baptism is a sacrament of initiation into the visible Church.[52] Wesleyan covenant theology further teaches that baptism is a sign and a seal of the covenant of grace:[53]

Of this great new-covenant blessing, baptism was therefore eminently the sign; and it represented "the pouring out" of the Spirit, "the descending" of the Spirit, the "falling" of the Spirit "upon men," by the mode in which it was administered, the pouring of water from above upon the subjects baptized. As a seal, also, or confirming sign, baptism answers to circumcision.[53]

Methodists recognize three modes of baptism as being valid—immersion, aspersion or affusion—in the name of the Holy Trinity.[54]

Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist

The followers of John Wesley have typically affirmed that the sacrament of Holy Communion is an instrumental Means of Grace through which the real presence of Christ is communicated to the believer,[55] but have otherwise allowed the details to remain a mystery.[56] In particular, Methodists reject the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (see "Article XVIII" of the Articles of Religion); the Primitive Methodist Church, in its Discipline also rejects the Lollardist doctrine of consubstantiation.[57] In 2004, the United Methodist Church affirmed its view of the sacrament and its belief in the real presence in an official document entitled This Holy Mystery: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy Communion. Of particular note here is the church's unequivocal recognition of the anamnesis as more than just a memorial but, rather, a re-presentation of Christ Jesus and His Love.[58]

- Holy Communion is remembrance, commemoration, and memorial, but this remembrance is much more than simply intellectual recalling. "Do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19; 1 Corinthians 11:24–25) is anamnesis (the biblical Greek word). This dynamic action becomes re-presentation of past gracious acts of God in the present, so powerfully as to make them truly present now. Christ is risen and is alive here and now, not just remembered for what was done in the past.

This affirmation of real presence can be seen clearly illustrated in the language of the United Methodist Eucharistic Liturgy[59] where, in the epiclesis of the Great Thanksgiving, the celebrating minister prays over the elements:

- Pour out your Holy Spirit on us gathered here, and on these gifts of bread and wine. Make them be for us the body and blood of Christ, that we may be for the world the body of Christ, redeemed by his blood.

Methodists assert that Jesus is truly present, and that the means of His presence is a "Holy Mystery". A celebrating minister will pray for the Holy Spirit to make the elements "be for us the body and blood of Christ", and the congregation can even sing, as in the third stanza of Charles Wesley's hymn Come Sinners to the Gospel Feast:

- Come and partake the gospel feast,

- be saved from sin, in Jesus rest;

- O taste the goodness of our God,

- and eat his flesh and drink his blood.

The distinctive feature of the Methodist doctrine of the real presence is that the way Christ manifests His presence in the Eucharist is a sacred mystery—the focus is that Christ is truly present in the sacrament.[60] The Discipline of the Free Methodist Church thus teaches:

The Lord's Supper is a sacrament of our redemption by Christ's death. To those who rightly, worthily, and with faith receive it, the bread which we break is a partaking of the body of Christ; and likewise the cup of blessing is a partaking of the blood of Christ. The supper is also a sign of the love and unity that Christians have among themselves. Christ, according to his promise, is really present in the sacrament. –Discipline, Free Methodist Church[61]

Confession

Confirmation

Holy Matrimony

Lovefeast

In Wesleyan theology, Lovefeasts (in which bread and the loving-cup is shared between members of the congregation) are a 'means of grace' and 'converting ordinance' that John Wesley believed to be an apostolic institution.[62] One account from July 1776 expounded on the fact that people experienced the new birth and entire sanctification at a Lovefeast:[62]

We held our general love-feast. It began between eight and nine on Wednesday morning, and continued till noon. Many testified that they had 'redemption in the blood of Jesus, even the forgiveness of sins.' And many were enabled to declare that it had 'cleansed them from all sin.' So clear, so full, so strong was their testimony that while some were speaking their experience hundreds were in tears, and others vehemently crying to God for pardon or holiness. About eight our watch-night began. Mr. J. preached an excellent sermon: the rest of the preachers exhorted and prayed with divine energy. Surely, for the work wrought on these two days, many will praise God to all eternity (ibid.: pp. 93–4)[62]

Validity of Holy Orders

John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist tradition, believed that the offices of bishop and presbyter constituted one order,[63] citing an ancient opinion from the Church of Alexandria;[63] Jerome, a Church Father, wrote: "For even at Alexandria from the time of Mark the Evangelist until the episcopates of Heraclas and Dionysius the presbyters always named as bishop one of their own number chosen by themselves and set in a more exalted position, just as an army elects a general, or as deacons appoint one of themselves whom they know to be diligent and call him archdeacon. For what function, excepting ordination, belongs to a bishop that does not also belong to a presbyter?" (Letter CXLVI).[64] John Wesley thus argued that for two centuries the succession of bishops in the Church of Alexandria, which was founded by Mark the Evangelist, was preserved through ordination by presbyters alone and was considered valid by that ancient Church.[65][66][67]

Since the Bishop of London refused to ordain ministers in the British American colonies,[68] this constituted an emergency and as a result, on 2 September 1784, Wesley, along with a priest from the Anglican Church and two other elders,[69] operating under the ancient Alexandrian habitude, ordained Thomas Coke a superintendent, although Coke embraced the title bishop.[70][71]

Today, the United Methodist Church follows this ancient Alexandrian practice as bishops are elected from the presbyterate:[72] the Discipline of the Methodist Church, in ¶303, affirms that "ordination to this ministry is a gift from God to the Church. In ordination, the Church affirms and continues the apostolic ministry through persons empowered by the Holy Spirit."[73] It also cites Scripture in support of this practice, namely, 1 Timothy 4:14, which states:

Neglect not the gift that is in thee, which was given thee by the laying on of the hands of the presbytery.[74]

The Methodist Church also buttresses this argument with the leg of sacred tradition of the Wesleyan Quadrilateral by citing the Church Fathers, many of whom concur with this view.[75][76]

In addition to the aforementioned arguments, in 1937 the annual Conference of the British Methodist Church located the "true continuity" with the Church of past ages in "the continuity of Christian experience, the fellowship in the gift of the one Spirit; in the continuity in the allegiance to one Lord, the continued proclamation of the message; the continued acceptance of the mission;..." [through a long chain which goes back to] "the first disciples in the company of the Lord Himself ... This is our doctrine of apostolic succession" [which neither depends on, nor is secured by,] "an official succession of ministers, whether bishops or presbyters, from apostolic times, but rather by fidelity to apostolic truth".[77]

Canonical hours

Early Methodism was known for its "almost monastic rigors, its living by rule, [and] its canonical hours of prayer".[78] It inherited from its Anglican patrimony the rubrics of reciting the Daily Office, which Methodist Christians were expected to pray.[79] The first prayer book of Methodism, The Sunday Service of the Methodists with other occasional Services thus included the canonical hours of both Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer; these two fixed prayer times were observed everyday in early Christianity, individually on weekdays and corporately on the Lord's Day.[79][80] Later Methodist liturgical books, such as The Methodist Worship Book (1999) provide for Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer to be prayed daily; the United Methodist Church encourages its communicants to pray the canonical hours as "one of the essential practices" of being a disciple of Jesus.[81] Some Methodist religious orders publish the Daily Office to be used for that community, for example, The Book of Offices and Services of The Order of Saint Luke contains the canonical hours to be prayed traditionally at seven fixed prayer times: Lauds (6 am), Terce (9 am), Sext (12 pm), None (3 pm), Vespers (6 pm), Compline (9 pm) and Vigil (12 am).[82]

Outward Holiness

Early Methodists wore plain dress, with Methodist clergy condemning "high headdresses, ruffles, laces, gold, and 'costly apparel' in general".[83] John Wesley recommended that Methodists annually read his thoughts On Dress;[84] in that sermon, John Wesley expressed his desire for Methodists: "Let me see, before I die, a Methodist congregation, full as plain dressed as a Quaker congregation".[85] The 1858 Discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Connection thus stated that "we would ... enjoin on all who fear God plain dress".[86] Peter Cartwright, a Methodist revivalist, stated that in addition to wearing plain dress, the early Methodists distinguished themselves from other members of society by fasting once a week, abstaining from alcohol, and devoutly observing the Sabbath.[87] Methodist circuit riders were known for practicing the spiritual discipline of mortifying the flesh as they "arose well before dawn for solitary prayer; they remained on their knees without food or drink or physical comforts sometimes for hours on end".[88] The early Methodists did not participate in, and condemned, "worldly habits" including "playing cards, racing horses, gambling, attending the theater, dancing (both in frolics and balls), and cockfighting".[83]

Over time, many of these practices were gradually relaxed in mainline Methodism, although practices such as teetotalism and fasting are still very much encouraged, in addition to the current prohibition of gambling;[89] denominations of the conservative holiness movement, such as the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection and Evangelical Wesleyan Church, continue to reflect the spirit of the historic Methodist practice of wearing plain dress, encouraging members in "abstaining from the wearing of extravagant hairstyles, jewelry—to include rings, and expensive clothing for any reason".[90][91] The General Rules of the Methodist Church in America, which are among the doctrinal standards of many Methodist Churches, promote first-day Sabbatarianism as they require "attending upon all the ordinances of God" including "the public worship of God" and prohibit "profaning the day of the Lord, either by doing ordinary work therein or by buying or selling".[92][93]

Law and Gospel

John Wesley admonished Methodist preachers to emphasize both the Law and the Gospel:[94]

Undoubtedly both should be preached in their turn; yea, both at once, or both in one. All the conditional promises are instances of this. They are law and gospel mixed together. According to this model, I should advise every preacher continually to preach the law — the law grafted upon, tempered by, and animated with the spirit of the gospel. I advise him to declare explain, and enforce every command of God. But meantime to declare in every sermon (and the more explicitly the better) that the flint and great command to a Christian is, ‘Believe in the Lord Jesus Christ’: that Christ is all in all, our wisdom, righteousness, sanctification, and redemption; that all life, love, strength are from Him alone, and all freely given to us through faith. And it will ever be found that the law thus preached both enlightens and strengthens the soul; that it both nourishes and teaches; that it is the guide, ‘ food, medicine, and stay’ of the believing soul.[94]

Methodism makes a distinction between the ceremonial law and the moral law that is the Ten Commandments given to Moses.[95] In Methodist Christianity, the moral law is the "fundamental ontological principle of the universe" and "is grounded in eternity", being "engraved on human hearts by the finger of God."[95] In contradistinction to the teaching of the Lutheran Churches, the Methodist Churches bring the Law and the Gospel together in a profound sense: "the law is grace and through it we discover the good news of the way life is intended to be lived."[95] John Wesley, the father of the Methodist tradition taught:[95]

... there is no contrariety at all between the law and the gospel; ... there is no need for the law to pass away in order to the establishing of the gospel. Indeed neither of them supersedes the other, but they agree perfectly well together. Yea, the very same words, considered in different respects, are parts both of the law and the gospel. If they are considered as commandments, they are parts of the law: if as promises, of the gospel. Thus, 'Thou shalt love the Lord the God with all thy heart,' when considered as a commandment, is a branch of the law; when regarded as a promise, is an essential part of the gospel-the gospel being no other than the commands of the law proposed by way of promises. Accordingly poverty of spirit, purity of heart, and whatever else is enjoined in the holy law of God, are no other, when viewed in a gospel light, than so many great and precious promises. There is therefore the closest connection that can be conceived between the law and the gospel. On the one hand the law continually makes way for and points us to the gospel; on the other the gospel continually leads us to a more exact fulfilling of the law .... We may yet further observe that every command in Holy Writ is only a covered promise. (Sermon 25, "Sermon on the Mount, V," II, 2, 3)[95]

Sunday Sabbatarianism

The first Methodists, who were Arminian in theology, were known for "religiously keeping the Sabbath day".[96] They regarded "keeping the Lord's Day as a duty, a delight, and a means of grace".[97] The General Rules of the Methodist Church require "attending upon all the ordinances of God" including "the public worship of God" and prohibit "profaning the day of the Lord, either by doing ordinary work therein or by buying or selling".[97][93] The Sunday Sabbatarian practices of the earlier Wesleyan Methodist Church in Great Britain are described by Jonathan Crowther in A Portraiture of Methodism:[98]

They believe it to be their duty to keep the first day of the week as a sabbath. This, before Christ, was on the last day of the week; but from the time of his resurrection, was changed into the first day of the week, and is in scripture called, The Lord's Day, and is to be continued to the end of the world as the Christian sabbath. This they believe to be set apart by God, and for his worship by a positive, moral, and perpetual commandment. And they think it to be agreeable to the law of nature, as well as divine institution, that a due proportion of time should be set apart for the worship of God. ... This day ought to be kept holy unto the Lord, and men and women ought so to order their affairs, and prepare their hearts, that they may not only have a holy rest on that day, from worldly employments, words, and thoughts, but spend the day in the public and private duties of piety. No part of the day should be employed in any other way, except in works of mercy and necessity. On this day, they believe it to be their duty to worship God, and that not only in form, but at the same time in spirit and in truth. Therefore, they employ themselves in prayer and thanksgiving, in reading and meditating on the scriptures, in hearing the public preaching of God's word, in singing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs, in Christian conversation, and in commemorating the dying love of the Lord Jesus Christ. ... And with them it is a prevailing idea, that God must be worshipped in spirit, daily, in private families, in the closet, and in the public assemblies.[98]

Churches upholding Wesleyan theology

The Methodist movement began as a reform within the Church of England, and, for a while, it remained as such. The movement separated itself from its "mother church" and became known as the Methodist Episcopal Church in America and the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Britain. Many divisions occurred within the Methodist Episcopal Church in the 19th century, mostly over, first, the slavery question and later, over the inclusion of African-Americans. Some of these schisms healed in the early twentieth century, and many of the splinter Methodist groups came together by 1939 to form The Methodist Church. In 1968, the Methodist Church joined with the Pietist Evangelical United Brethren Church to form The United Methodist Church, the largest Methodist church in America. Other groups include the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, the Congregational Methodist Church, the Evangelical Church of North America, the Evangelical Congregational Church, the Evangelical Methodist Church, the Free Methodist Church of North America, and the Southern Methodist Church.

In 19th-century America, a dissension arose over the nature of sanctification. Those who emphasized the gradual nature sanctification remained within the mainline Methodist Churches; others, however, believed in instantaneous sanctification that could be perfected. Those who followed the latter line of thought began the various holiness churches,[99] including the Church of God (Holiness), the Church of God (Anderson), the Churches of Christ in Christian Union, and the Wesleyan Methodist Church, which later merged with the Pilgrim Holiness Church to form the Wesleyan Church, which is present today. Other holiness groups, which also rejected the competing Pentecostal movement, merged to form the Church of the Nazarene. The Salvation Army is another Wesleyan-Holiness group which traces its roots to early Methodism. The Salvation Army's founders Catherine and William Booth founded the organization to stress evangelism and social action when William was a minister in the Methodist Reform Church.

The conservative holiness movement, including denominations such as the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection, Bible Methodist Connection of Churches, Evangelical Wesleyan Church and Primitive Methodist Church, emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries to herald many of the strict standards of primitive Methodism, including outward holiness, plain dress, and temperance.[100]

References

Citations

- Commonplace Holiness: Wesley & Methodism

- Stanglin, Keith D.; McCall, Thomas H. (2012). Jacob Arminius: Theologian of Grace. Oxford University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780199755677.

- Stevens, Abel (1858). The History of the Religious Movement of the Eighteenth Century, called Methodism. 1. London: Carlton & Porter. p. 155.

- Joyner, F. Belton (2007). United Methodist Questions, United Methodist Answers: Exploring Christian Faith. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780664230395. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

The new birth is necessary for salvation because it marks the move toward holiness. That comes with faith.

- Stokes, Mack B. (1998). Major United Methodist Beliefs. Abingdon Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780687082124.

- "The Articles of Religion of the Methodist Church XVI-XVIII". The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church. The United Methodist Church. 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

Article XVII—Of Baptism: Baptism is not only a sign of profession and mark of difference whereby Christians are distinguished from others that are not baptized; but it is also a sign of regeneration or the new birth. The Baptism of young children is to be retained in the Church.

- The Methodist Visitor. Elliot Stock, 62, Paternoster Row, E.C. 1876. p. 137.

Ye must be born again." Yield to God that He may perform this work in and for you. Admit Him to your heart. "Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved.

- Richey, Russell E.; Rowe, Kenneth E.; Schmidt, Jean Miller (19 January 1993). Perspectives on American Methodism: interpretive essays. Kingswood Books. ISBN 9780687307821. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Rothwell, Mel-Thomas; Rothwell, Helen F. (1998). A Catechism on the Christian Religion: The Doctrines of Christianity with Special Emphasis on Wesleyan Concepts. Schmul Publishing Co. p. 53.

- Elwell, Walter A. (1 May 2001). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology (Baker Reference Library). Baker Publishing Group. p. 1268. ISBN 9781441200303.

This balance is most evident in Wesley's understanding of faith and works, justification and sanctification. ... Wesley himself in a sermon entitled "Justification by Faith" makes an attempt to define the term accurately. First, he states what justification is not. It is not being made actually just and righteous (that is sanctification). It is not being cleared of the accusations of Satan, nor of the law, nor even of God. We have sinned, so the accusation stands. Justification implies pardon, the forgiveness of sins. ... Ultimately for the true Wesleyan salvation is completed by our return to original righteousness. This is done by the work of the Holy Spirit. ... The Wesleyan tradition insists that grace is not contrasted with law but with the works of the law. Wesleyans remind us that Jesus came to fulfill, not destroy the law. God made us in his perfect image, and he wants that image restored. He wants to return us to a full and perfect obedience through the process of sanctification. ... Good works follow after justification as its inevitable fruit. Wesley insisted that Methodists who did not fulfill all righteousness deserved the hottest place in the lake of fire.

- Robinson, Jeff (25 August 2015). "Meet a Reformed Arminian". TGC. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

Reformed Arminianism’s understanding of apostasy veers from the Wesleyan notion that individuals may repeatedly fall from grace by committing individual sins and may be repeatedly restored to a state of grace through penitence.

- Campbell, Ted A. (1 October 2011). Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials, 2nd Edition. Abingdon Press. pp. 40, 68–69. ISBN 9781426753473.

- Knight III, Henry H. (9 July 2013). "Wesley on Faith and Good Works". AFTE. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Wagner, Amy (20 January 2014). "Wesley on Faith, Love, and Salvation". AFTE. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Joyner, F. Belton (2007). United Methodist Answers. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 80. ISBN 9780664230395.

Jacob Albright, founder of the movement that led to the Evangelical Church flow in The United Methodist Church, got into trouble with some of his Lutheran, Reformed, and Mennonite neighbors because he insisted that salvation not only involved ritual but meant a change of heart, a different way of living.

- Jones, Scott J. (2002). United Methodist Doctrine. Abingdon Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780687034857.

- Sawyer, M. James (11 April 2016). The Survivor's Guide to Theology. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 363. ISBN 9781498294058.

- Langford, Andy; Langford, Sally (2011). Living as United Methodist Christians: Our Story, Our Beliefs, Our Lives. Abingdon Press. p. 45. ISBN 9781426711930.

- Tennent, Timothy (9 July 2011). "Means of Grace: Why I am a Methodist and an Evangelical". Asbury Theological Seminary. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Bucher, Richard P. (2014). "Methodism". Lexington: Lutheran Church Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014.

- Mallalieu, Willard Francis (1903). The Fullness of the Blessing of the Gospel of Christ. Jennings and Pye. p. 28.

- Wood, Darren Cushman (2007). "John Wesley's Use of Atonement". The Asbury Journal. 62 (2): 55–70.

- "John Wesley's Conversion Place Memorial – The 'Aldersgate Flame'". Methodist Heritage. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- http://www.ccel.org/ccel/wesley/journal.vi.ii.xvi.html

- The Works of John Wesley, 10:288. In his Sermon: "The Repentance of Believers," Wesley proclaimed, "For, by that faith in his life, death, and intercession for us, renewed from moment to moment, we are every whit clean, and there is ... now no condemnation for us ... By the same faith we feel the power of Christ every moment resting upon us ... whereby we are enabled to continue in spiritual life ... As long as we retain our faith in him, we 'draw water out of the wells of salvation'" (The Works of John Wesley, 5:167).

- The Works of John Wesley, 10:297.

- The Works of John Wesley, 10:298.

- This is the rubric for the hymn in the 1935 (U.S.) Methodist hymn book.

- Synan, Vinson (1997). The Holiness-Pentecostal tradition: Charismatic movements in the twentieth century. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8028-4103-2. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Alexander, Donald L.; Ferguson, Sinclair B. (1988). Christian spirituality: five views of sanctification. InterVarsity Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8308-1278-3. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Curtis, Harold (2006-09-21). Following the Cloud: A Vision of the Convergence of Science and the Church. Harold Curtis. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4196-4571-6. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Southey, Robert (1820). The life of Wesley: and the rise and progress of Methodism. Evert Duyckinck and George Long; Clayton & Kingsland, printers. p. 80. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- Rodes, Stanley J. (25 September 2014). From Faith to Faith: John Wesley's Covenant Theology and the Way of Salvation. James Clarke & Co. pp. 7, 62–76. ISBN 9780227902202.

- Wesley, John. "Sermon 6 – The Righteousness Of Faith". The Wesley Center Online. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Crowther, Jonathan (1815). A Portraiture of Methodism. p. 224.

- Gibson, James. "Wesleyan Heritage Series: Entire Sanctification". South Georgia Confessing Association. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Newton, William F. (1863). The Magazine of the Wesleyan Methodist Church. J. Fry & Company. p. 673.

- Bloom, Linda (20 July 2007). "Vatican stance "nothing new" say church leader". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- William J. Abraham (25 August 2016). "The Birth Pangs of United Methodism as a Unique, Global, Orthodox Denomination". Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Davies, Rupert E.; George, A. Raymond; Rupp, Gordon (14 June 2017). A History of the Methodist Church in Great Britain, Volume Three. Wipf & Stock Publishers. p. 225. ISBN 9781532630507.

- United Methodist Church (2004). The book of discipline of the United Methodist Church. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-687-02373-4. OCLC 58046917.

- Withington, John Swann (1878). The United Methodist Free Churches' Magazine. London: Thomas Newton. p. 685.

The country is called Hades. That portion of it which is occupied by the good is called Paradise, and that province which is occupied by the wicked is called Gehenna.

- Smithson, William T. (1859). The Methodist Pulpit. H. Polkinhornprinter. p. 363.

Besides, continues our critical authority, we have another clear proof from the New Testament, that hades denotes the intermediate state of souls between death and the general resurrection. In Revelations (xx, 14) we read that death and hades-by our translators rendered hell, as usual-shall, immediately after the general judgment, "be cast into the lake of fire: this is the second death." In other words, the death which consists in the separation of soul and body, and the receptacle of disembodied spirits shall be no more. Hades shall be emptied, death abolished.

- Jr., Charles Yrigoyen; Warrick, Susan E. (16 March 2005). Historical Dictionary of Methodism. Scarecrow Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780810865464.

Considering the question of death and the intermediate state, John Wesley affirmed the immortality of the soul (as well as the future resurrection of the body), denied the reality of purgatory, and made a distinction between hell (the receptacle of the damned) and hades (the receptacle of all separate spirits), and also between paradise (the antechamber of heaven) and heaven itself.

- Karen B. Westerfield Tucker (8 March 2001). American Methodist Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780198029267. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

Decisions made during life were therefore inseparably connected to what came after life. Upon death, according to Wesley, the souls of the deceased would enter an intermediate, penultimate state in which they would remain until reunited with the body at the resurrection of the dead. In that state variously identified as "the ante-chamber of heaven," "Abraham's bosom," and "paradise".

- Swartz, Alan (20 April 2009). United Methodists and the Last Days. Hermeneutic. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012.

Wesley believed that when we die we will go to an Intermediate State (Paradise for the Righteous and Hades for the Accursed). We will remain there until the Day of Judgment when we will all be bodily resurrected and stand before Christ as our Judge. After the Judgment, the Righteous will go to their eternal reward in Heaven and the Accursed will depart to Hell (see Matthew 25).

- Walker, Walter James (1885). Chapters on the Early Registers of Halifax Parish Church. Whitley & Booth. p. 20.

The opinion of the Rev. John Wesley may be worth citing. "I believe it to be a duty to observe, to pray for the Faithful Departed."

- Holden, Harrington William (1872). John Wesley in Company with High Churchmen. London: J. Hodges. p. 84.

Wesley taught the propriety of Praying for the Dead, practised it himself, provided Forms that others might. These forms, for daily use, he put fort, not tentatively or apologetically, but as considering such prayer a settled matter of Christian practice, with all who believe that the Faithful, living and dead, are one Body in Christ in equal need and like expectation of those blessings which they will together enjoy, when both see Him in His Kingdom. Two or three examples, out of many, may be given:--"O grant that we, with those who are already dead in Thy faith and fear, may together partake of a joyful resurrection."

- Gould, James B. (4 August 2016). Understanding Prayer for the Dead: Its Foundation in History and Logic. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 57–58. ISBN 9781620329887.

The Roman Catholic and English Methodist churches both pray for the dead. Their consensus statement confirms that "over the centuries in the Catholic tradition praying for the dead has developed into a variety of practices, especially through the Mass. ... The Methodist church ... has prayers for the dead ... Methodists who pray for the dead thereby commend them to the continuing mercy of God."

- Understanding Four Views on Baptism. Zondervan. 30 August 2009. p. 92. ISBN 9780310866985.

Thomas J. Nettles, Richard L. Pratt Jr., Robert Kolb, John D. Castelein

- "By Water and the Spirit: A United Methodist Understanding of Baptism". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

In United Methodist churches, the water of baptism may be administered by sprinkling, pouring, or immersion.

- Stuart, George Rutledge; Chappell, Edwin Barfield (1922). What Every Methodist Should Know. Lamar & Barton. p. 83.

- Summers, Thomas Osmond (1857). Methodist Pamphlets for the People. E. Stevenson & F. A. Owen for the M. E. Church, South. p. 18.

- The Discipline of the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection (Original Allegheny Conference). Salem: Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection. 2014. p. 140.

- "This Holy Mystery: Part One". The United Methodist Church GBOD. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "This Holy Mystery: Part Two". The United Methodist Church GBOD. Archived from the original on 7 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Discipline of the Primitive Methodist Church in the United States of America. Primitive Methodist Church. 2013.

We reject the doctrine of transubstantiation: that is, that the substance of bread and wine are changed into the very body and blood of Christ in the Lord's Supper. We likewise reject that doctrine which affirms the physical presence of Christ's body and blood to be by, with and under the elements of bread and wine (consubstantiation).

- This Holy Mystery: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy Communion. (PDF). General Conference of The United Methodist Church, 2004.

- for example, "United Methodist Communon Liturgy: Word and Table 1". revneal.org. 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

- Neal, Gregory S. (19 December 2014). Grace Upon Grace. WestBow Press. p. 107. ISBN 9781490860060.

- Oden, Thomas C. (2008). Doctrinal Standards in the Wesleyan Tradition: Revised Edition. Abingdon Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780687651115.

- Tovey, Phillip (24 February 2016). The Theory and Practice of Extended Communion. Routledge. pp. 40–49. ISBN 9781317014201.

- McClintock, John (1894). Cyclopædia of Biblical, theological, and ecclesiastical literature, Volume 6. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Wesley had believed that bishops and presbyters constituted but one order, with the same right to ordain. He knew that for two centuries the succession of bishops in the Church of Alexandria was preserved through ordination by presbyters alone. "I firmly believe", he said, "I am a scriptural ἐπίσκοπος, as much as any man in England or in Europe; for the uninterrupted succession I know to be a fable which no man ever did or can prove;" but he also held that "Neither Christ nor his apostles prescribe any particular form of Church government." He was a true bishop of the flock which God had given to his care. He had hitherto refused "to exercise this right" of ordaining, because he would not come into needless conflict with the order of the English Church to which he belonged. But after the Revolution, his ordaining for American would violate no law of the Church; and when the necessity was clearly apparent, his hesitation ceased. "There does not appear," he said, "any other way of supplying them with ministers." Having formed his purpose, in February 1784, he invited Dr. Coke to his study in City Road, laid the case before him, and proposed to ordain and send him to America.

- Hixon, Daniel McLain (5 September 2010). "Methodists and Apostolic Succession". Gloria Deo. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

The succession normally proceeds from bishop to bishop, however, in certain instances where the death of a bishop made this impossible, groups of elders have consecrated new bishops, who in turn have been recognized as legitimate by the broader catholic Church. We read of one example of this in the Ancient Church in St. Jerome's Letter CXLVI when he describes the episcopal succession of the city of Alexandria. Thus, considering the unusual historical circumstances of Christians in the American colonies cut off from valid sacraments, Fr. John Wesley's action in consecrating Thomas Coke was irregular but not invalid, and the United Methodist Church enjoys a valid succession to this day.

- The Cambridge Medieval History Series, Volumes 1–5. Plantagenet Publishing. p. 130.

Severus of Antioch, in the sixth century, mentions that "in the former days" the bishop was "appointed" by presbyters at Alexandria. Jerome (in the same letter that was cited above, but independent for the moment of Ambrosiaster) deduces the essential equality of priest and bishop from the consideration that the Alexandrian bishop "down to Heraclas and Dionysius" (232–265) was chosen by the presbyters from among themselves without any special form of consecration.

- Hinson, E. Glenn (1995). The Church Triumphant: A History of Christianity Up to 1300. Mercer University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780865544369.

In Alexandria presbyters elected bishops and installed them until the fourth century. Throughout this critical era the power and importance of bishops increased steadily. At the beginning of the period Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Clement of Alexandria still thought of bishops as presbyters, albeit presbyters in a class by themselves.

- McClintock, John; Strong, James (1894). Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. 6. Harper. p. 170.

For forty years Mr. Wesley had believed that bishops and presbyters constituted but one order, with the same right to ordain. He knew that for two centuries the succession of bishops in the Church of Alexandria was preserved through ordination by presbyters alone.

- Separated Brethren: A Review of Protestant, Anglican, Eastern Orthodox & Other Religions in the United States. Our Sunday Visitor. 2002. ISBN 9781931709057. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

the Methodists were directed to receive baptism and Holy Communion from Episcopal priests. They soon petitioned to receive the sacraments from the same Methodist preachers who visited their homes and conducted their worship services. The Bishop of London refused to ordain Methodist preachers as deacons and priests for the colonies, so in 1784 Wesley assumed the power to ordain ministers himself.

- The historic episcopate: a study of Anglican claims and Methodist orders. Eaton & Mains. 1896. p. 145. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

IN September, 1784, the Rev. John Wesley, assisted by a presbyter of the Church of England and two other elders, ordained by solemn imposition of the hands of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Coke to the episcopal office.

- Appleton's cyclopædia of American biography, Volume 6. D. Appleton & Company. 1889. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Being refused, he conferred with Thomas Coke, a presbyter of the Church of England, and with others, and on 2 Sept., 1784, he ordained Coke bishop, after ordaining Thomas Vasey and Richard Whatcoat as presbyters, with his assistance and that of another presbyter.

- A compendious history of American Methodism. Scholarly Publishing Office. 1885. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Wesley referes(sic) to the ordination of bishops by the presbyters of Alexandria, in justification of his ordination of Coke.

- "The Ministry of the Elder". United Methodist Church. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "Seven Days of Preparation – A Guide for Reading, Meditation and Prayer for all who participate in The Conversation: A Day for Dialogue and Discernment: Ordering of Ministry in the United Methodist Church" (PDF). United Methodist Church. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

The Discipline affirms that "ordination to this ministry is a gift from God to the Church. In ordination, the Church affirms and continues the apostolic ministry through persons empowered by the Holy Spirit" (¶303).

- Episcopal Methodism, as it was, and is;: Or, An account of the origin, progress, doctrines, church polity, usages, institutions, and statistics, of the Methodist Episcopal church in the United States. Miller, Orton & Mulligan. 1852. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

"Neglect not the gift that is in thee, which was given thee by the laying on of the hands of the presbytery." Here it is plain that the ministerial gift or power which Timothy possessed, was given him by the laying on of the hands of the body of the elders who ordained him. And in regard to the government of the church, it is equally plain that bishops, in distinction from presbyters, were not charged with the oversight thereof, for it is said – Acts xx. 17, 28, that Paul "called the elders (not the bishops) of the Church of Ephesus, and said unto them, 'Take heed therefore to yourselves, and to all the flock over which the Holy Ghost hath made you overseers,' feed the church of God." On this passage we remark, 1st, that the original Greek term for the word "overseer" is "episcopos," they very word from which our term "bishop" is derived, and which is generally translated "bishop" in the English version of the New Testament. Now this term episcopos, overseer, or bishop, is applied to the identical persons called elders in the 17th verse, and to none other. Consequently, Paul must have considered elders and bishops as one, not only in office, but in order also; and so the Ephesian ministers undoubtedly understood him.

- The Methodist Ministry Defended, Or, a Reply to the Arguments in Favour of the Divine Institution, and the Uninterrupted Succession of Episcopacy. General Books LLC. 1899. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

Even "after the introduction of the practice by which the epithet Bishop was generally confined to one person, the older writers who dwell upon this, occasionally use that epithet as synonymous with presbyter, it not having been till the third century, that the appropriation was so complete as never to be cast out of view.

- Episcopal Methodism, as it was, and is;: Or, An account of the origin, progress, doctrines, church polity, usages, institutions, and statistics, of the Methodist Episcopal church in the United States. Miller, Orton & Mulligan. 1852. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

But if Scripture is opposed to modern high church claims and pretensions, so is history, on which successionists appear to lay so much stress.

- Jay, Eric G. The Church: its changing image through twenty centuries. John Knox Press: 1980, p.228f

- Hurst, John Fletcher (1902). The History of Methodism. Eaton & Mains. p. 310.

- Jones, Susan H. (30 April 2019). Everyday Public Worship. SCM Press. ISBN 978-0-334-05757-4.

- Beckwith, Roger T. (2005). Calendar, Chronology And Worship: Studies in Ancient Judaism And Early Christianity. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 978-90-04-14603-7.

- "Praying the Hours of the Day: Recovering Daily Prayer". General Board of Discipleship. 6 May 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- The Book of Offices and Services. Order of St. Luke. 6 September 2012.

- Lyerly, Cynthia Lynn (24 September 1998). Methodism and the Southern Mind, 1770–1810. Oxford University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9780195354249. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- Journals of Wesley, Nehemiah Curnock, ed., London: Epworth Press 1938, p. 468.

- Wesley, John (1999). "The Wesley Center Online: Sermon 88 – On Dress". Wesley Center for Applied Theology. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- The Discipline of the Wesleyan Methodist Connection, of America. Wesleyan Methodist Connection of America. 1858. p. 85.

- Cartwright, Peter (1857). Autobiography of Peter Cartwright: The Backwoods Preacher. Carlton & Porter. p. 74.

- Bratt, James D. (2012). By the Vision of Another World: Worship in American History. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 9780802867100.

Methodist preachers, in particular, may have been tempted to take the elevation of the spirit and concomitant mortification of the body to extremes. Early circuit riders often arose well before dawn for solitary prayer; they remained on their knees without food or drink or physical comforts sometimes for hours on end.

- Jones, Scott J. (2002). United Methodist Doctrine: The Extreme Center. Abingdon Press. p. 235. ISBN 9780687034857.

- "I. The Church". Discipline of the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection. Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection.

Should we insist on plain and modest dress? Certainly. We should not on any account spend what the Lord has put into our hands as stewards, to be used for His glory, in expensive wearing apparel, when thousands are suffering for food and raiment, and millions are perishing for the Word of life. Let the dress of every member of every Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Church be plain and modest. Let the strictest carefulness and economy be used in these respects.

- The Discipline of the Evangelical Wesleyan Church. Evangelical Wesleyan Church. 2015. pp. 41, 57–58.

- Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield (27 April 2011). American Methodist Worship. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780199774159.

- Abraham, William J.; Kirby, James E. (24 September 2009). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 253. ISBN 9780191607431.

- "Wesley on Preaching Law and Gospel". Seedbed. 25 August 2016.

- Dayton, Donald W. (1991). "Law and Gospel in the Wesleyan Tradition" (PDF). Grace Theological Journal. 12 (2): 233–243.

- Peter Cartwright (1857). Autobiography of Peter Cartwright: The Backwoods Preacher. Carlton & Porter. p. 74.

- Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield (27 April 2011). American Methodist Worship. Oxford University Press. pp. 46, 117. ISBN 9780199774159.

- Crowther, Jonathan (1815). A Portraiture of Methodism: Or, The History of the Wesleyan Methodists. T. Blanshard. pp. 224, 249–250.

- "Holiness churches". www.oikoumene.org. World Council of Churches. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Sidwell, Mark, "Conservative Holiness Movement: A Fundamentalism File Report". Retrieved 6 February 2021.

Sources

- Huzar, Eleanor, "Arminianism" in the Encyclopedia Americana (Danbury, 1994).

- Outler, Albert C., "John Wesley" in the Encyclopedia Americana (Danbury, 1994).

- J. Wesley (ed. T. Jackson), Works (14 vols).

Further reading

- Mel-Thomas & Helen Rothwell (1998). A Catechism on the Christian Religion: The Doctrines of Christianity with Special Emphasis on Wesleyan Concepts. Nicholasville: Schmul Publishing Co. ISBN 0880193867.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- A Catechism Prepared Especially for the Members of the Evangelical Wesleyan Church. Cooperstown: LWD Publishing. 2014.

- Wallace Thornton, Jr., Radical Righteousness

- Wallace Thornton, Jr., The Conservative Holiness Movement: A Historical Appraisal

- Steve Harper, The Way to Heaven: The Gospel According to John Wesley

- Kenneth J. Collins, Wesley on Salvation

- Kenneth J. Collins, The Scripture Way of Salvation

- Harald Lindström, Wesley and Sanctification

- Thomas C. Oden, John Wesley's Scriptural Christianity

- Adam Clarke, Clarke's Christian Theology

- John Wesley, The Works of John Wesley (Baker Books, 2002)