Whiplash (medicine)

Whiplash is a non-medical term describing a range of injuries to the neck caused by or related to a sudden distortion of the neck[1] associated with extension,[2] although the exact injury mechanisms remain unknown. The term "whiplash" is a colloquialism. "Cervical acceleration–deceleration" (CAD) describes the mechanism of the injury, while the term "whiplash associated disorders" (WAD) describes the injury sequelae and symptoms.

| Whiplash | |

|---|---|

| |

| Lateral view X-ray of whiplash showing a loss of normal lordosis of the cervical spine | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

Whiplash is commonly associated with motor vehicle accidents, usually when the vehicle has been hit in the rear;[3] however, the injury can be sustained in many other ways, including headbanging,[4] bungee jumping and falls.[5] It is one of the most frequently claimed injuries on vehicle insurance policies in certain countries; for example, in the United Kingdom 430,000 people made an insurance claim for whiplash in 2007, accounting for 14% of every driver's premium.[6]

Before the invention of the car, whiplash injuries were called "railway spine" as they were noted mostly in connection with train collisions. The first case of severe neck pain arising from a train collision was documented around 1919.[7] The number of whiplash injuries has since risen sharply due to rear-end motor vehicle collisions. Given the wide variety of symptoms associated with whiplash injuries, the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders coined the phrase 'Whiplash-Associated Disorders'.[7]

While there is broad consensus that acute whiplash is not uncommon, the topic of chronic whiplash is controversial, with studies in at least three countries showing zero to low prevalence, and some academics positing a linkage to financial issues.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms reported by sufferers include: pain and aching to the neck and back, referred pain to the shoulders, sensory disturbance (such as pins and needles) to the arms and legs, and headaches. Symptoms can appear directly after the injury, but often are not felt until days afterwards.[3] Whiplash is usually confined to the spine. The most common areas of the spine affected by whiplash are the neck and middle of the spine. "Neck" pain is very common between the shoulder and the neck. The "missing link" of whiplash may be towards or inside the shoulder and this would explain why neck therapy alone frequently does not give lasting relief.[9][10][11][12][13]

Cognitive symptoms following whiplash trauma, such as being easily distracted or irritated, seems to be common and possibly linked to a poorer prognosis.[14]

Cause

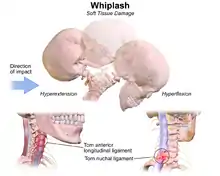

The exact injury mechanism that causes whiplash injuries is forceful sudden hyperextension followed by hyperflexion of the cervical vertebrae, mainly spraining the nuchal ligament and the Anterior Longitudinal Ligament respectively. A whiplash injury may be the result of impulsive retracting of the spine, mainly the ligament: anterior longitudinal ligament which is stretched or tears, as the head snaps forward and then back again causing a whiplash injury.[15]

A whiplash injury from an automobile accident is called a cervical acceleration–deceleration injury. Cadaver studies have shown that as an automobile occupant is hit from behind, the forces from the seat back compress the kyphosis of the thoracic spine, which provides an axial load on the lumbar spine and cervical spine. This forces the cervical spine to deform into an S-shape where the lower cervical spine is forced into a kyphosis while the upper cervical spine maintains its lordosis. As the injury progresses, the whole cervical spine is finally hyper-extended.

Whiplash may be caused by any motion similar to a rear-end collision in a motor vehicle, such as may take place on a roller coaster[16] or other rides at an amusement park, sports injuries such as skiing accidents, other modes of transportation such as airplane travel, or from being hit, kicked or shaken.[17].

Whiplash associated disorders sometimes include injury to the cerebrum. In a severe cervical acceleration–deceleration syndrome, a brain injury known as a coup-contra-coup injury occurs. A coup-contra-coup injury occurs as the brain is accelerated into the cranium as the head and neck hyperextend, and is then accelerated into the other side as the head and neck rebound to hyper-flexion or neutral position.

"Volunteer studies of experimental, low-velocity rear-end collisions have shown a percentage of subjects to report short-lived symptoms",[18]

From this type of research, it has been inferred that whiplash symptoms might not always have any pathological (injury) explanation.

However, over the last decade, academic surgeons in the UK and US have sought to unravel the whiplash enigma. A 1000-case, four-year observational study published in 2012 said that the "missing link" in whiplash injuries is the trapezius muscle which may be damaged through eccentric muscle contraction during the whiplash mechanism described above and below.[9] Another study[19] suggested that "shneck pain" was in the nearby supraspinatus muscle and this resulted from a seemingly asymptomatic form of shoulder impingement. Shoulder impingement is commonly asymptomatic[20] and the shoulder may be injured along with the neck in a motor vehicle accident. Whiplash due to The Referred Shoulder Impingement Syndrome was successfully treated using conventional treatments for shoulder impingement including anti-inflammatory steroids and non steroids, and by avoiding the overhead position of shoulder impingement during the day and night time.[21] All of this work demonstrates that historically and indeed presently whiplash patients' pain sources may be missed if it is outside of the neck. Hence the pathology in whiplash may have been missed and the treatment ineffective.

Mechanism

Whiplash can be described as a sudden strain to the muscles, bones and nerves in the neck. The neck is made up of seven vertebrae, referred to as the cervical vertebrae. The first two cervical vertebrae, the axis and atlas, are shaped differently from the remaining five. The atlas and axis are responsible for movement of the skull from side to side (cervical rotation to the right and left); also moving forward and backward (cervical flexion and extension). Excessive extension and flexion can disrupt the vertebrae.

There are four phases that occur during "whiplash": Initial position (before the collision), retraction, extension and rebound. In the initial position there is no force on the neck it is stable due to inertia.[22] Anterior longitudinal ligament injuries in whiplash may lead to cervical instability.[23] They explain that during the retraction phase that is when the actual "whiplash" occurs, since there is an unusual loading of soft tissues. The next phase is the extension, the whole neck and head switches to extension, and it is stopped or limited by the head restraint. The rebound phase transpires as result of the phases that are mentioned.

During the retraction phase, the spine forms an S-Shaped curve, and this caused by the flexion in the upper planes and hyperextension at the lower planes and this exceed their physiological limits this phase the injuries occur to the lower cervical vertebrae. At the extension phase, all cervical vertebrae and the head are fully extended, but do not surpass their physiological limits. Most of the injuries happen in C-5 and C-6.[24]

Pathophysiology

While the time associated with a specific collision will vary, the following provides an example of the occupant and seat interaction sequence for a collision lasting approximately 300 milliseconds.

| 0 ms |

|

|---|---|

| 100 ms |

|

| 150 ms |

|

| 175 ms |

|

| 300 ms |

|

Diagnosis

Diagnosis occurs through a patient history, head and neck examination, X-rays to rule out bone fractures and may involve the use of medical imaging to determine if there are other injuries.[25]

Québec Task Force

The Québec Task Force (QTF) has divided whiplash-associated disorders into five grades.[26]

- Grade 0: no neck pain, stiffness, or any physical signs are noticed

- Grade 1: neck complaints of pain, stiffness or tenderness only but no physical signs are noted by the examining physician.

- Grade 2: neck complaints and the examining physician finds decreased range of motion and point tenderness in the neck.

- Grade 3: neck complaints plus neurological signs such as decreased deep tendon reflexes, weakness and sensory deficits.

- Grade 4: neck complaints and fracture or dislocation, or injury to the spinal cord.

Prevention

The focus of preventive measures to date has been on the design of car seats, primarily through the introduction of head restraints, often called headrests. This approach is potentially problematic given the underlying assumption that purely mechanical factors cause whiplash injuries — an unproven theory. So far the injury reducing effects of head restraints appears to have been low, approximately 5–10%, because car seats have become stiffer in order to increase crashworthiness of cars in high-speed rear-end collisions which in turn could increase the risk of whiplash injury in low-speed rear impact collisions. Improvements in the geometry of car seats through better design and energy absorption could offer additional benefits. Active devices move the body in a crash in order to shift the loads on the car seat.[3]

For the last 40 years, vehicle safety researchers have been designing and gathering information on the ability of head restraints to mitigate injuries resulting from rear-end collisions. As a result, different types of head restraints have been developed by various manufactures to protect their occupants from whiplash.[27] Below are definitions of different types of head restraints.[28]

Head restraint — refers to a device designed to limit the rearward displacement of an adult occupant's head in relation to the torso in order to reduce the risk of injury to the cervical vertebrae in the event of a rear impact. The most effective head restraint must allow a backset motion of less than 60 mm to prevent the hyperextension of the neck during impact.[29]

Integrated head restraint or fixed head restraint — refers to a head restraint formed by the upper part of the seat back, or a head restraint that is not height adjustable and cannot be detached from the seat or the vehicle structure except by the use of tools or following the partial or total removal of the seat furnishing".

Adjustable head restraint — refers to a head restraint that is capable of being positioned to fit the morphology of the seated occupant. The device may permit horizontal displacement, known as tilt adjustment, and/or vertical displacement, known as height adjustment.

Active head restraint — refers to a device designed to automatically improve head restraint position and/or geometry during an impact".

Automatically adjusting head restraint — refers to a head restraint that automatically adjusts the position of the head restraint when the seat position is adjusted.

A major issue in whiplash prevention is the lack of proper adjustment of the seat safety system by both drivers and passengers. Studies have shown that a well designed and adjusted head restraint could prevent potentially injurious head-neck kinematics in rear-end collisions by limiting the differential movement of the head and torso. The primary function of a head restraint is to minimize the relative rearward movement of the head and neck during rear impact. During a rear-end collision, the presence of an effective head restraint behind the occupant's head can limit the differential movement of the head and torso. A properly placed head restraint where one can sufficiently protect his/her head lower the chances of head injury by up to 35% during a rear-end collision.[30][31]

In contrast to a properly adjusted head restraint, research suggests that there may be an increased risk of neck injuries if the head restraint is incorrectly positioned. More studies by manufacturers and automobile safety organizations are currently undergoing to examine the best ways to reduce head and torso injuries during a rear-end impact with different geometries of the head restraint and seat-back systems.

In most passenger vehicles where manually adjustable head restraints are fitted, proper use requires sufficient knowledge and awareness by occupants. When driving, the height of the head restraint is critical in influencing injury risk. A restraint should be at least as high as the head's center of gravity, or about 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) below the top of the head. The backset, or distance behind the head, should be as small as possible. Backsets of more than 10 centimeters (about 4 inches) have been associated with increased symptoms of neck injury in crashes. In a sitting position, the minimum height of the restraint should correspond to the top of the driver's ear or even higher. In addition, there should be minimal distance between the back of head and the point where it first meets the restraint.

Due to low public awareness of the consequence of incorrect positioning of head restraints, some passenger vehicle manufactures have designed and implemented a range of devices into their models to protect their occupants.

Some current systems are:

- Mercedes-Benz A-Class Active Head Restraint (AHR)[3][32],

- Saab (Responsible for the first active head restraint), Opel, Ford, Nissan, Subaru, Hyundai, and Peugeot — Active Head restraint (SAHR)[3][33],

- Volvo and Jaguar — Whiplash Protection System/Whiplash Prevention System (WHIPS)[34], and

- Toyota — Whiplash Injury Lessening (WIL).[3]

The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) and other testing centers around the world have been involved in testing the effectiveness of head restraint and seat systems in laboratory conditions to assess their ability to prevent or mitigate whiplash injuries. They have found that over 60% of new motor vehicles on the market have "good" rated head restraints. Various organisations exist which list such vehicles

Management

Rehabilitation (e.g. physical therapy)

Symptoms remaining more than six months after trauma is labelled Whiplash syndrome. The main purpose with early rehabilitation is to reduce the risk for development of Whiplash syndrome. Early rehabilitation for whiplash depends on the grade category. It can be categorized as grade 0 being no pain to grade 4 with a cervical bone fracture or dislocation. Grade 4 obviously needs admission to hospital while grade 0-3 can be managed as outpatients. The symptoms from the potential injury to the cervical spine may be debilitating, and pain was reported to be one of the biggest stressor events experienced in daily living, so it is important to begin rehabilitation immediately to prevent future pain.[35]

Current research supports that active mobilization rather than a soft collar results in a more prompt recovery both in the short[36] and long term[37] perspective. Furthermore, Schnabel and colleagues stated that the soft collar is not a suitable medium for rehabilitation, and the best way of recovery is to include an active rehabilitation program that includes physical therapy exercises and postural modifications.[36] Another study found patients who participated in active therapy shortly after injury increased mobilization of the neck with significantly less pain within four weeks when compared to patients using a cervical collar.[38]

Active treatments are light repetitive exercises that work the area to maintain normality. Basic information is also given to teach the patient that exercises as instructed will not cause any damage to their neck. These exercises are done at home or under the care of a health professional.[39] When beginning a rehabilitation regimen, it's important to begin with slow movements which include cervical rotation until pain threshold three to five times per day, flexion and extension of the shoulder joint by moving the arms up and down two to three times, and combining shoulder raises while inhaling and releasing the shoulder raise while exhaling.[35] Soderlund and colleagues also recommend that these exercises should be done every day until pain starts to dissipate.[35] Early mobilization is important for preventing chronic pain, but pain experienced from these exercises might cause psychological symptoms that could have negative impact on recovery.[40] Rosenfeld found that doing active exercises as often as once every waken hour during one month after trauma decreases the need for sick leave three years after trauma from 25% to 5.7%.[37]

Passive treatments such as acupuncture, massage therapy, and stimulation may sometimes be used as a complement to active exercises.[41] Return to normal activities of daily living should be encouraged as soon as possible to maximize and expedite full recovery.[42]

For chronic whiplash patients, rehabilitation is recommended. Patients who entered a rehabilitation program said they were able to control their pain, they continued to use strategies that were taught to them, and were able to go back to their daily activities.[43] A Cochrane review published in 2007 found that evidence neither supports nor refutes the effectiveness conservative treatments including physiotherapy, acupuncture, or a collar to treat Grades 1 or 2.[44]

Medications

According to the recommendations made by the Quebec Task Force, treatment for individuals with whiplash associated disorders grade 1–3 may include non-narcotic analgesics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may also be prescribed in the case of WAD 2 and WAD 3, but their use should be limited to a maximum of three weeks. Botulinum toxin A is used to treat involuntary muscle contraction and spasms. Botulinum toxin type-A is only temporary and repeated injections need to take place in order to feel the effects.[45]

According to a year long follow-up study in 2008 on 186 patients, the WAD-classification and Quebec Task Force regimen were not linked to better clinical outcomes.[46]

Prognosis

The consequences of whiplash range from mild pain for a few days (which is the case for most people),[47] to severe disability. It seems that around 50% will have some remaining symptoms.[37][48]

Alterations in resting state cerebral blood flow have been demonstrated in patients with chronic pain after whiplash injury.[49] There is evidence for persistent inflammation in the neck in patients with chronic pain after whiplash injury.[50]

There has long been a proposed link between whiplash injuries and the development of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD). A recent review concluded that although there are contradictions in the literature, overall there is moderate evidence that TMD can occasionally follow whiplash injury, and that the incidence of this occurrence is low to moderate.[51]

Epidemiology

Whiplash is the term commonly used to describe hyperflexion and hyperextension,[52] and is one of the most common nonfatal car crash injuries. More than one million whiplash injuries occur each year due to car crashes. This is an estimate because not all cases of whiplash are reported. In a given year, an estimated 3.8 people per 1000 experience whiplash symptoms.[53] "Freeman and co-investigators estimated that 6.2% of the US population have late whiplash syndrome".[54] The majority of cases occur in patients in their late fourth decade. Unless a cervical strain has occurred with additional brain or spinal cord trauma mortality is rare.[53]

Whiplash can occur at speeds of fifteen miles per hour or less; it is the sudden jolt, as one car hits another, that causes one's head to be abruptly thrown back and sideways. The more sudden the motion, the more bones, discs, muscles and tendons in ones neck and upper back will be damaged. Spinal cord injuries are responsible for about 6,000 deaths in the US each year and 5,000 whiplash injuries per year result in quadriplegia.[52]

After 12 months, only 1 in 5 patients remain symptomatic, only 11.5% of individuals were able to return to work a year after the injury, and only 35.4% were able to get back to work at a similar level of performance after 20 years. Estimated indirect costs to industry are $66,626 per year, depending on the level and severity. Lastly, the total cost per year was $40.5 billion in 2008, a 317% increase over 1998.[52]

Incidence

Altogether it is of note that, especially in many Western countries, after a motor vehicle collision those involved seek health care for the assessment of injuries and for insurance documentation purposes. In contrast, in many less wealthy countries, there may be limited access to care and insurance may only be available to the wealthy. Against this background, the “(late) whiplash syndrome” (ICD-10: S13.4) has been one special focus of continuous and controversial scientific research since the 1950s[55][56] as the worldwide incidence of such injuries varies enormously, from 16-2000 per 100,000 population, and the late whiplash syndrome in these cases varies between 18% to 40%.[57] Thus, important work by Schrader et al. in The Lancet showed that late whiplash syndrome after a motor vehicle collision is rare or uncommon in Lithuania,[58] and Cassidy et al.’s conclusion in the New England Journal of Medicine is that “the elimination of compensation for pain and suffering is associated with a decreased incidence and improved prognosis of whiplash injury”.[59]

Moreover, an experimental study in 2001 places participants in a stationary vehicle with a curtain blocking their rear view, and exposed them to a simulated rear-end collision. Twenty percent of patients had symptoms at 3 days, despite the fact that no collision actually occurred.[60]

From the evolving viewpoint of naturalistic Internet search engine analytics in has been shown in 2017 that the expectations for receiving compensation may influence Internet search behavior in relation to whiplash injury.[61]

See also

References

- Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. "Q&A: Neck Injury". Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- "whiplash" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Krafft, M; Kullgren A; Lie A; Tingval C (2005-04-01). "Assessment of Whiplash Protection in Rear Impacts" (PDF). Swedish National Road Administration & Folksam. Retrieved 2016-01-10.

- "Whiplash". 2017-10-23.

- (2010). Retrieved January 16, 2013 from http://www.njpcc.com/conditions-of-the-spine/neck-paininjury.html

- "Warning over whiplash 'epidemic'". BBC News. 2008-11-15. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Desapriya, Ediriweera (2010). Head restraints and whiplash : the past, present, and future. New York: Nova Science Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61668-150-0.

- NY Times - In one country chronic whiplash is uncompensated - and unknown

- Bismil QM, Bismil MS (2012). "Myofascial-entheseal dysfunction in chronic whiplash injury". J R Soc Med Sh Rep. 3 (8): 57. doi:10.1258/shorts.2012.012052. PMC 3434435. PMID 23301145.

- Gorski JM and Schwartz LH, Shoulder Impingement Presenting as Neck Pain. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery Vol 85-A · Number 4 · April 2003 p635-638

- Chauhan SK, Peckham T, Turner R (2003). "Impingement Syndrome Associated with Whiplash Injury". J Bone Joint Surg. 85-B (3): 408–410. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.85B3.13503. PMID 12729119.

- Umaar W. Yew KIM; Zenios M.; Brett I.; Sharma Y. (2005). "Whiplash Injury of the Shoulder: Is it a Distinct Clinical Entity?". Acta Orthop. Belg. 71: 385–387.

- Abbassian A.; Giddins G. (2008). "Subacromial Impingement in Patients with Whiplash Injury to the Cervical Spine". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 3 (25): 1749. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-3-25. PMC 2443117. PMID 18582391.

- Borenstein, P.; Rosenfeld, M.; Gunnarsson, R. (2010). "Cognitive symptoms, cervical range of motion and pain as prognostic factors after whiplash trauma" (PDF). Acta Neurol Scand. 122 (4): 278–85. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2009.01305.x. PMID 20003080.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Whiplash

- Roller Coaster Neck Pain, from the Spinal Injury Foundation

- "Whiplash injury". 2006-08-23.

- Castro, W. H.; Meyer, S. J.; Becke, M. E.; Nentwig, C. G.; Hein, M. F.; Ercan, B. I.; Thomann, S.; Wessels, U.; Du Chesne, A. E. (2001). "No stress--no whiplash? Prevalence of "whiplash" symptoms following exposure to a placebo rear-end collision". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 114 (6): 316–322. doi:10.1007/s004140000193. PMID 11508796.

- Gorski JM and Schwartz LH, Shoulder Impingement Presenting as Neck Pain. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery April 1, 2003 vol. 85 no. 4 p635-638

- Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders" J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1699-704

- Gorski JM and Schwartz LH, Shoulder Impingement Presenting as Neck Pain. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery VOL 85-A · NUMBER 4 · APRIL 2003 p635-638(ibid)

- Stemper, D. B., Yoganandan, N., Pintar, A.F., and Rao D.R. (2006)

- Medical Engineering And Physics, 28(6), 515-524.

- Panjabi M.M.; Cholewicki J.; Nibu K.; Grauer N.J; Babat B.L.; Dvorack J. (1998). "Mechanism of whiplash injury". Clinical Biomechanics. 13 (4–5): 239–249. doi:10.1016/s0268-0033(98)00033-3. PMID 11415793.

- "Whiplash — Topic Overview". WebMD. 2006-11-16. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- Pastakia, Khushnum; Kumar, Saravana (2011-04-27). "Acute whiplash associated disorders (WAD)". Open Access Emergency Medicine. 3: 29–32. doi:10.2147/OAEM.S17853. ISSN 1179-1500. PMC 4753964. PMID 27147849.

- Zuby DS, Lund AK (April 2010). "Preventing minor neck injuries in rear crashes—forty years of progress". J. Occup. Environ. Med. 52 (4): 428–33. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181bb777c. PMID 20357685.

- Desapriya, Ediriweera (2010). Head restraints and whiplash : the past, present, and future. New York: Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-61668-150-0.

- Stemper, BD.; Yoganandan, N.; Pintar, FA. (Mar 2006). "Effect of head restraint backset on head-neck kinematics in whiplash". Accid Anal Prev. 38 (2): 317–23. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2005.10.005. PMID 16289336.

- Farmer CM, Wells JK, Lund AK (June 2003). "Effects of head restraint and seat redesign on neck injury risk in rear-end crashes". Traffic Inj Prev. 4 (2): 83–90. doi:10.1080/15389580309867. PMID 16210192.

- Farmer CM, Zuby DS, Wells JK, Hellinga LA (December 2008). "Relationship of dynamic seat ratings to real-world neck injury rates". Traffic Inj Prev. 9 (6): 561–7. doi:10.1080/15389580802393041. PMID 19058103.

- Long Fibre-Reinforced Polyamide for Crash-Active Car Headrests, August 22, 2006

- Top Safety Ratings For Saab Active Head Restraints, UK Motor Search Engine, August 22, 2006

- Volvo Seat Is Benchmark For Whiplash Protection, Volvo Owners Club, August 22, 2006

- Bring, A.; Soderlund, A.; Wasteson, E.; Asenlöf, P. (2012). "Daily stressors in patients with acute whiplash associated disorders". Disabil Rehabil. 34 (21): 1783–9. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.662571. PMID 22512410.

- Schnabel, M.; Ferrari, R.; Vassiliou, T.; Kaluza, G. (May 2004). "Randomised, controlled outcome study of active mobilisation compared with collar therapy for whiplash injury". Emerg Med J. 21 (3): 306–10. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.010165. PMC 1726332. PMID 15107368.

- Rosenfeld, M.; Seferiadis, A.; Carlsson, J.; Gunnarsson, R. (2003). "Active intervention in patients with whiplash-associated disorders improves long-term prognosis: a randomized controlled clinical trial". Spine. 28 (22): 2491–8. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000090822.96814.13. PMID 14624083.

- Logan, AJ.; Holt, MD. (Jul 2003). "Management of whiplash injuries presenting to accident and emergency departments in Wales". Emerg Med J. 20 (4): 354–5. doi:10.1136/emj.20.4.354. PMC 1726150. PMID 12835348.

- Lundmark, H & Persson, A.L. (2006)

- Sterner, Y.; Gerdle, B. (Sep 2004). "Acute and chronic whiplash disorders--a review". J Rehabil Med. 36 (5): 193–209, quiz 210. doi:10.1080/16501970410030742. PMID 15626160.

- SoÈderlund, A. & Lindberg P. (2001). Cognitive behavioural components in physiotherapy management of chronic whiplash associated disorders (WAD) a randomised group study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 17,

- Gurumoorthy D, Twomey L (1996). "The Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders". Spine. 21 (7): 897–8. doi:10.1097/00007632-199604010-00027. PMID 8779026.

- Rydstad, M.; Schult, ML.; Löfgren, M. (2010). "Whiplash patients' experience of a multimodal rehabilitation programme and its usefulness one year later". Disabil Rehabil. 32 (22): 1810–8. doi:10.3109/09638281003734425. PMID 20350208.

- Verhagen, Arianne P; Scholten-Peeters, Gwendolijne GGM; van Wijngaarden, Sandra; de Bie, Rob; Bierma-Zeinstra, Sita MA (2007-04-18). "Conservative treatments for whiplash". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003338.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858.

- Juan, FJ. (Feb 2004). "Use of botulinum toxin-A for musculoskeletal pain in patients with whiplash associated disorders [ISRCTN68653575]". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 5 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-5-5. PMC 356919. PMID 15018625.

- Kivioja J, Jensen I, Lindgren U (2008). "Neither the WAD-classification nor the Quebec Task Force follow-up regimen seems to be important for the outcome after a whiplash injury. A prospective study on 186 consecutive patients". Eur Spine J. 17: 930–5. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0675-0. PMC 2443268. PMID 18427841.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ferrari R, Schrader H (2001). "The late whiplash syndrome: a biopsychosocial approach". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 70 (6): 722–6. doi:10.1136/jnnp.70.6.722. PMC 1737376. PMID 11385003.

- Bunketorp, L.; Stener-Victorin, E.; Carlsson, J. (2005). "Neck pain and disability following motor vehicle accidents--a cohort study". Europ Spine. 14 (1): 84–9. doi:10.1007/s00586-004-0766-5. PMC 3476670. PMID 15241671.

- Linnman C, Appel L, Furmark T, et al. (April 2010). "Ventromedial prefrontal neurokinin 1 receptor availability is reduced in chronic pain". Pain. 149 (1): 64–70. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.008. PMID 20137858.

- Linnman C, Appel L, Fredrikson M, et al. (2011). "Elevated [11C]-D-deprenyl uptake in chronic Whiplash Associated Disorder suggests persistent musculoskeletal inflammation". PLoS ONE. 6 (4): e19182. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619182L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019182. PMC 3079741. PMID 21541010.

- Fernandez, CE; Amiri, A; Jaime, J; Delaney, P (Dec 2009). "The relationship of whiplash injury and temporomandibular disorders: a narrative literature review". Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 8 (4): 171–86. doi:10.1016/j.jcm.2009.07.006. PMC 2786231. PMID 19948308.

- Foreman, Stephen M.; Croft, Arthur C. (2002). Whiplash injuries : the cervical acceleration/deceleration syndrom. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-2681-8.

- Barnsley, L.; Lord, S.; Bogduk, N. (Sep 1994). "Whiplash injury". Pain. 58 (3): 283–307. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(94)90123-6. PMID 7838578.

- Freeman, MD.; Croft, AC.; Rossignol, AM.; Weaver, DS.; Reiser, M. (January 1999). "A review and methodologic critique of the literature refuting whiplash syndrome". Spine. 24 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1097/00007632-199901010-00022. PMID 9921598.

- Ferrari R, Shorter E (Nov 2003). "From railway spine to whiplash--the recycling of nervous irritation". Med Sci Monit. 9 (11): HY27–37.

- Ferrari R, Kwan O, Russell AS, Pearce JM, Schrader H (1999). "The best approach to the problem of whiplash? one ticket to Lithuania, please". Clin Exp Rheumatol. 17 (3): 321–6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chappuis G, Soltermann B, Aredoc CEA, Number Ceredoc (Oct 2008). "results from the comparative study by CEA, AREDOC and CEREDOC". Eur Spine J. 17 (10): 1350–7. doi:10.1007/s00586-008-0732-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schrader H, Obelieniene D, Bovim G, Surkiene D, Mickeviciene D, Miseviciene I, Sand T (1996). "Natural evolution of late whiplash syndrome outside the medicolegal context". Lancet. 347 (9010): 1207–11. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90733-3.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren A (2000). "Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury". N Engl J Med. 342 (16): 1179–86. doi:10.1056/NEJM200004203421606.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Castro WH, Meyer SJ, Becke ME, Nentwig CG, Hein MF, Ercan BI, Thomann S, Wessels U, Du Chesne AE (2001). "No stress--no whiplash? Prevalence of 'whiplash' symptoms following exposure to a placebo rear-end collision". Int J Legal Med. 114 (6): 316–22.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Noll-Hussong M (2017). "Whiplash Syndrome Reloaded: Digital Echoes of Whiplash Syndrome in the European Internet Search Engine Context". JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. 3 (1): e15. doi:10.2196/publichealth.7054.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Look up Whiplash in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Car accident. |