White-breasted nuthatch

The white-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) is a small songbird of the nuthatch family common across much of temperate North America. It is stocky, with a large head, short tail, powerful bill, and strong feet. It has a black cap, white face, chest, and flanks, blue-gray upperparts, and a chestnut lower belly. Its nine subspecies differ mainly in the color of the body plumage.

| White-breasted nuthatch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male S. c. carolinensis in Algonquin Provincial Park, Canada | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Sittidae |

| Genus: | Sitta |

| Species: | S. carolinensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Sitta carolinensis Latham, 1790 | |

| |

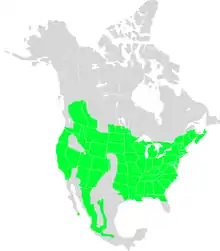

| Approximate year-round range[2][3] | |

Like other nuthatches, the white-breasted nuthatch forages for insects on trunks and branches and is able to move head-first down trees. Seeds form a substantial part of its winter diet, as do acorns and hickory nuts stored in the fall. Old-growth woodland is preferred for breeding. The nest is in a hole in a tree, and the breeding pair may smear insects around the entrance as a deterrent to squirrels. Predators include hawks, owls, and snakes. Forest clearance may lead to local habitat loss, but there are no major conservation concerns over most of its range.

Taxonomy

The nuthatches are a genus, Sitta, of small passerine birds which derive their English name from the propensity of some species to wedge large insects or seeds into cracks, and then hack at them with their strong bills.[4] Sitta is derived from sittē, the Ancient Greek for nuthatch,[5] and carolinensis means "of Carolina" in Latin. The white-breasted nuthatch was first described by English ornithologist John Latham in his 1790 work, the Index Ornithologicus.[6]

Nuthatch taxonomy is complex, with geographically separated species sometimes closely resembling each other. The white-breasted nuthatch has an appearance and contact call similar to those of the white-cheeked nuthatch, Sitta leucopsis, of the Himalayas and was formerly considered to be conspecific with it.[2] A study published in 2012 showed that four distinct lineages were genetically isolated from each other and could represent different species, recognizable by morphology and song.[7] A molecular phylogeny published in 2014 and including all main species' lineages within nuthatches concluded that the white-breasted nuthatch was more closely related to the giant nuthatch (S. magna) than to S. przewalskii, formerly regarded as possibly conspecific with it; S. przewalskii turned out to be basal in the family.[8]

Description

Like other members of its genus, the white-breasted nuthatch has a large head, short tail, short wings, a powerful bill and strong feet; it is 13–14 cm (5.1–5.5 in) long, with a wingspan of 20–27 cm (7.9–10.6 in) and a weight of 18–30 g (0.63–1.06 oz).[3]

The adult male of the nominate subspecies, S. c. carolinensis, has pale blue-gray upperparts, a glossy black cap (crown of the head), and a black band on the upper back. The wing coverts and flight feathers are very dark gray with paler fringes, and the closed wing is pale gray and black, with a thin white wing bar. The face and the underparts are white. The outer tail feathers are black with broad diagonal white bands across the outer three feathers, a feature readily visible in flight.[2]

The female has, on average, a narrower black back band, slightly duller upperparts and buffer underparts than the male. Her cap may be gray, but many females have black caps and cannot be reliably distinguished from the male in the field. In the northeastern United States, at least 10% of females have black caps, but the proportion rises to 40–80% in the Rocky Mountains, Mexico and the southeastern U.S. Juveniles are similar to the adult, but duller plumaged.[2]

Like other nuthatches, this is a noisy species with a range of vocalizations. The male's mating song is a rapid nasal qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui-qui. The contact call between members of a pair, given most frequently in the fall and winter is a thin squeaky nit, uttered up to 30 times a minute. A more distinctive sound is a shrill kri repeated rapidly with mounting anxiety or excitement kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri-kri; the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin subspecies have a higher, faster yididitititit call,[2] and Pacific birds a more nasal beeerf.[9]

Three other, significantly smaller, nuthatches have ranges which overlap that of white-breasted, but none has white plumage completely surrounding the eye. Further distinctions are that the red-breasted nuthatch has a black eye line and reddish underparts, and the brown-headed and pygmy nuthatches each have a brown cap, and a white patch on the nape of the neck.[9]

Geographical variation

The white-breasted nuthatch has nine subspecies, although the differences are small and change gradually across the range. The subspecies are sometimes treated as three groups based on close similarities in morphology, habitat usage, and vocalizations. These groups cover eastern North America, the Great Basin and central Mexico, and the Pacific coastal regions.[9] The subspecies of the western interior have the darkest upperparts, and eastern S. c. carolinensis has the palest back.[2] The eastern form also has a thicker bill and broader dark cap stripe than the interior and Pacific races. The calls of the three groups differ, as described above.[9] The Great Basin and Eastern forms have been observed in secondary contact on the Great Plains, where they do not seem to mix.

| Subspecies[2] | Range | Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| S. c. carolinensis | Nominate subspecies, northeast North America west to Saskatchewan and eastern Texas | Palest back and cap |

| S. c. nelsoni | Rocky Mountains, from northern Montana south to extreme northwest Chihuahua | Darker gray upperparts, darker cap, less contrast in wings |

| S. c. tenuissima | From British Columbia through the Cascade Range to southern California | Smaller than S. c. nelsoni, with slightly paler upperparts and a more slender bill |

| S. c. aculeata | Western parts of Washington, Oregon and California, northernmost Baja California. | Smaller than S. c. tenuissima, with buffer underparts, slightly paler upperparts and a more slender bill |

| S. c. alexandrae | Northern Baja California | Larger than S. c. aculeata, with marginally darker upperparts. The longest-billed race |

| S. c. lagunae | Southernmost Baja California | Smaller than S. c. alexandrae with slightly darker; underparts and more buff. Bill relatively stout |

| S. c. oberholseri | Southwest Texas and eastern Mexico | Very similar to S. c. nelsoni, but upperparts and underparts slightly darker |

| S. c. mexicana | Western Mexico | Duller than S. c. oberholseri with grayer flanks |

| S. c. kinneari | Southern Mexico in Guerrero and Oaxaca | Smallest subspecies, similar to S. c. mexicana but female has more extensively orange-buff underparts. Short, stout bill |

Distribution and habitat

The breeding habitat of the white-breasted nuthatch is woodland across North America, from southern Canada to northern Florida and southern Mexico. In the eastern part of its range, its preferred habitat is old-growth open deciduous or mixed forest, including orchards, parks, suburban gardens and cemeteries; it is found mainly in the lowlands, although it breeds at 1,675 m (5,495 ft) altitude in Tennessee. In the west and Mexico, this nuthatch is found in open montane pine-oak woodlands, and nesting occurs at up to 3,200 m (10,500 ft) altitude in Nevada, California and Mexico.[2] Pinyon-juniper and riverside woodlands may be used locally where available.[10] The white-breasted nuthatch is the only North American nuthatch usually found in deciduous trees; red-breasted, pygmy and brown-headed nuthatches prefer pines.[9]

The presence of mature or decaying trees with holes suitable for nesting is essential, and trees such as oak, beech and hickory are favored in the east since they also provide edible seeds.[2] White-breasted nuthatches seldom notch out their own nest like Red-breasted nuthatches.[11] and although suitable habitat is distributed continentally, it is discontinuous. The separate populations of this non-migratory species have diverged to form distinct regional subspecies.[12]

This nuthatch, like most of its genus, is non-migratory, and the adults normally stay in their territory year-round. There may be more noticeable dispersal due to seed failure or high reproductive success in some years,[13] and this species has occurred as a vagrant to Vancouver Island, Santa Cruz Island, and Bermuda. One bird landed on the RMS Queen Mary six hours' sailing east of New York City in October 1963.[2]

Behavior

Breeding

_-NMP_6-11-12_3.jpg.webp)

The white-breasted nuthatch is monogamous, and pairs form following a courtship in which the male bows to the female, spreading his tail and drooping his wings while swaying back and forth; he also feeds her morsels of food.[13] The pair establish a territory of 0.1–0.15 km2 (25–37 acres) in woodland, and up to 0.2 km2 (49 acres) in semi-wooded habitats, and then remain together year-round until one partner dies or disappears.[14] The nest cavity is usually a natural hole in a decaying tree, sometimes an old woodpecker nest.[2]

The nest hole is usually 3–12 m (9.8–39.4 ft) high in a tree and is lined with fur, fine grass, and shredded bark. The clutch is 5 to 9 eggs which are creamy-white, speckled with reddish brown, and average 19 mm × 14 mm (0.75 in × 0.55 in) in size. The eggs are incubated by the female for 13 to 14 days prior to hatching, and the altricial chicks fledge in a further 18 to 26 days.[3] Both adults feed the chicks in the nest and for about two weeks after fledging, and the male also feeds the female while she is incubating. Once independent, juveniles leave the adults' territory and either establish their own territory or become "floaters", unpaired birds without territories. It is probably these floaters which are mainly involved in the irregular dispersals of this species. This species of nuthatch roosts in tree holes or behind loose bark when not breeding and has the unusual habit of removing its feces from the roost site in the morning. It usually roosts alone except in very cold weather, when up to 29 birds have been recorded together.[2]

Predation

Predators of adult nuthatches include owls and diurnal birds of prey (such as sharp-shinned and Cooper's hawks), and nestlings and eggs are eaten by woodpeckers, small squirrels, and climbing snakes such as the western rat snake. The white-breasted nuthatch responds to predators near the nest by flicking its wings while making hn-hn calls. When a bird leaves the nest hole, it wipes around the entrance with a piece of fur or vegetation; this makes it more difficult for a predator to find the nest using its sense of smell.[14] The nuthatch may also smear blister beetles around the entrance to its nest, and it has been suggested that the unpleasant smell from the crushed insects deters squirrels, its chief competitor for natural tree cavities.[15] The estimated average lifespan of this nuthatch is two years,[14] but the record is twelve years and nine months.[13]

This nuthatch's responses to predators may be linked to a reproductive strategy. A study compared the white-breasted nuthatch with the red-breasted nuthatch in terms of the willingness of males to feed incubating females on the nest when presented with models of predators. The models were of a sharp-shinned hawk, which hunts adult nuthatches, and a house wren, which destroys eggs.[16] The white-breasted nuthatch is shorter-lived than the red-breasted nuthatch, but has more young, and was found to respond more strongly to the egg predator, whereas the red-breasted showed greater concern with the hawk. This supports the theory that longer-lived species benefit from adult survival and future breeding opportunities, while birds with shorter life spans place more value on the survival of their larger broods.[16]

Feeding

The white-breasted nuthatch forages along tree trunks and branches in a similar way to woodpeckers and treecreepers, but does not use its tail for additional support, instead progressing in jerky hops using its strong legs and feet. All nuthatches are distinctive when seeking food because they are able to descend tree trunks head-first and can hang upside-down beneath twigs and branches.[17][18]

This nuthatch is omnivorous, eating insects and seeds. It places large food items such as acorns or hickory nuts in crevices in tree trunks, and then hammers them open with its strong beak; surplus seeds are cached under loose bark or crevices of trees.[13] The diet in winter may be nearly 70% seeds, but in summer it is mainly insects. The insects consumed by the white-breasted nuthatch include caterpillars, ants, and pest species such as pine weevils, oystershell and other scale insects, and jumping plant lice.[14][19][20] This bird will occasionally feed on the ground, and readily visits feeding stations for nuts, suet and sunflower seeds, the last of which it often takes away to store.[13] The white-breasted nuthatch was also observed visiting raccoon latrines in order to find seeds.[21]

The white-breasted nuthatch often travels with small mixed flocks in winter. These flocks are led by titmice and chickadees, with nuthatches and downy woodpeckers as common attendant species. Participants in such flocks are thought to benefit in terms of foraging and predator avoidance. It is likely that the attendant species also access the information carried in the chickadees' calls and reduce their own level of vigilance accordingly.[22]

Status

.jpg.webp)

The white-breasted nuthatch is a common species with a large range, estimated at 8,600,000 km2 (3,300,000 sq mi). Its total population is estimated at 10 million individuals, and there is evidence of an overall population increase, so it is not believed to approach either the size criterion (fewer than 10,000 mature individuals) or the population decline criterion (declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations) of the IUCN Red List. For these reasons, the species is evaluated as Least Concern.[1]

The removal of dead trees from forests may cause problems locally for this species because it requires cavity sites for nesting; declines have been noted in Washington, Florida, and more widely in the southeastern U.S. west to Texas. In contrast, the breeding range is expanding in Alberta, and numbers are increasing in the northeast due to regrown forest.[2][23][24] This nuthatch is protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, to which the three countries in which it occurs (Canada, Mexico, and the United States) are all signatories.[14]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Sitta carolinensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22711202A94283783. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22711202A94283783.en.

- Harrap, Simon; Quinn, David (1996). Tits, Nuthatches and Treecreepers. Christopher Helm. pp. 150–155. ISBN 0-7136-3964-4.

- "White-breasted Nuthatch". Cornell Lab of Ornithology Bird Guide. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- "Nuthatch". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- Brookes, Ian (editor-in-chief) (2006). The Chambers Dictionary (ninth ed.). Edinburgh: Chambers. p. 1417. ISBN 0-550-10185-3.

- Latham, John (1790). Index Ornithologicus, sive Systema ornithologiae (in Latin). Volume 1. London: Leigh & Sotheby. p. 262.

- Walström, V Woody; Spellman, John (2012). "Speciation in the White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis): a multilocus perspective". Molecular Ecology. 21 (4): 907–920. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05384.x. PMID 22192449. S2CID 8775100.

- Pasquet, Éric; Barker, F Keith; Martens, Jochen; Tillier, Annie; Cruaud, Corinne & Cibois, Alice (April 2014). "Evolution within the nuthatches (Sittidae: Aves, Passeriformes): molecular phylogeny, biogeography, and ecological perspectives". Journal of Ornithology. 155 (3): 755. doi:10.1007/s10336-014-1063-7. S2CID 17637707.

- Sibley, David (2000). The North American Bird Guide. Pica Press. pp. 380–382. ISBN 1-873403-98-4.

- Ryser, Fred A; Dewey, Jennifer Owings (illustrator) (1985). Birds of the Great Basin: A Natural History. University of Nevada Press. p. 404. ISBN 0-87417-080-X.

- "All About Birds - White-breasted Nuthatch Life History - Nesting". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Spellman, Garth M; Klicka, John (April 2007). "Phylogeography of the white-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis): diversification in North American pine and oak woodlands". Molecular Ecology. 16 (8): 1729–1740. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03237.x. PMID 17402986. S2CID 25041554.

- Fergus, Charles; Hansen, Amelia (illustrator) (2000). Wildlife of Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Stackpole Books. pp. 275–276. ISBN 0-8117-2899-4.

- Pravosudov, Vladimir V.; Grubb. Thomas C. (1993) White-breasted nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis) in Poole, A.; Gill, F. (eds) The Birds of North America, volume 54. Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences; Washington, D.C.: The American Ornithologists' Union. 1–16

- Kilham, Lawrence (January 1971). "Use of in bill-sweeping by White-breasted Nuthatch" (PDF). Auk. 88: 175–176. doi:10.2307/4083981. JSTOR 4083981.

- Ghalambor, Cameron K.; Martin, Thomas E. (August 2000). "Parental investment strategies in two species of nuthatch vary with stage-specific predation risk and reproductive effort" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 60 (2): 263–267. doi:10.1006/anbe.2000.1472. PMID 10973729. S2CID 13165711.

- Matthysen, Erik; Löhrl, Hans (2003). "Nuthatches". In Perrins, Christopher (ed.). Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. pp. 536–537. ISBN 1-55297-777-3.

- Fujita, M.; K. Kawakami; S. Moriguchi & H. Higuchi (2008). "Locomotion of the Eurasian nuthatch on vertical and horizontal substrates". Journal of Zoology. 274 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00395.x.

- Hamid, Abdul; Odell, Thomas M.; Katovich, Steven. "White Pine Weevil". Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 21. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- Leslie, Anne R. (1994). Handbook of Integrated Pest Management for Turf and Ornamentals. CRC Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 0-87371-350-8.

- Page, L Kristen; Swihart, Robert K; Kazacos, Kevin R (1999). "Implications of raccoon latrines in the epizootiology of Baylisascariasis" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 35 (3): 474–480. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-35.3.474. PMID 10479081. S2CID 33801350. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2017.

- Dolby, Andrew S; Grubb Jr, Thomas C (1999). "Functional roles in mixed-species foraging flocks: A Field manipulation". The Auk. 116 (2): 557–559. doi:10.2307/4089392. JSTOR 4089392.

- "White-breasted Nuthatch Sitta carolinensis" (PDF). Florida's breeding bird atlas: A collaborative study of Florida's birdlife. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2003. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- "White-breasted Nuthatch Sitta carolinensis". BirdWeb – Seattle Audubon's guide to the birds of Washington. Seattle Audubon Society. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sitta carolinensis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Sitta carolinensis. |

- "White-breasted Nuthatch media". Internet Bird Collection.

- White-breasted Nuthatch – Sitta carolinensis – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- White-breasted Nuthatch photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)