Wildcat banking

Wildcat banking was the issuance of currency in the United States by privately-organized, state-chartered banks. These wildcat banks flourished alongside more centralized state banks during the Free Banking Era from 1837 to 1865, when the country had no national currency. Railroads and other capital-intensive businesses might, in the absence of an alternative, establish a bank to produce the money notes that they needed to carry on business, and state regulations were applied ineffectively if at all.[1] The National Bank Act of 1863 left currency issuance in the hands of private banks, but placed the issues on a more uniform basis, and imposed a tax on the state bank notes to remove them from circulation.

Origin

The term "wildcat banking" arose in reference to the Michigan banking boom. Promptly upon becoming a state in 1837, Michigan passed the General Banking Act, which allowed any group of landowners to organize a bank by raising at least $50,000 capital stock and depositing notes on real estate with the government as security for their bank notes. This law was unprecedented in a country where legislatures normally chartered each bank with a separate act. Although it was a regulated system in theory, the commissioners appointed to regulate the banks lacked the resources to do so effectively. A total of 49 banks were established, a surprising number given the capital requirement, and in time several were found to have cheated the law by watering their stock with phony contributions or passing cash from one bank to another ahead of the visiting commissioners.[2][3]

The banks issued currency notes that could be redeemed in specie only at rural locations, assuming cash was on hand. Commissioner Alpheus Felch recalled that one bank's "cash reserves" consisted of boxes of nails and glass topped with silver coins. Anyone who received the notes had to discount them according to their expected redemption value. According to a contemporary newspaper report:

"Michigan money is thus classed—First quality, Red Dog; second quality, Wild Cat; third quality, Catamount. Of the best quality, it is said, it takes five pecks to make a bushel."[4]

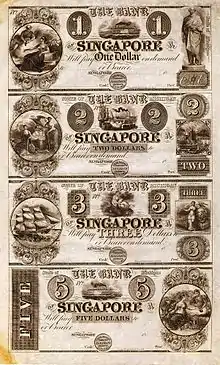

How these particular terms became associated with the notes is not known.[3] A counterfeit note in the collection of Eric P. Newman that features a mountain lion has become known as the "true wild cat note," but it purports to be an 1828 note of the Catskill Bank in New York, with no apparent connection to the events in Michigan.[5] A more common explanation is that the banks located their offices in inaccessible areas where animals outnumbered people.[6]

In response to these abuses, Michigan suspended new charters under the act. It attempted to create a single closely regulated state bank modeled on the neighboring Bank of Indiana, but was unable to raise the necessary capital. States continued to experiment with banking regulation in the absence of a federal policy, while Arkansas and Iowa prohibited banks entirely.

Practices

Wildcat banks were banks of issue rather than deposit banks. Their business focused on providing a medium of exchange to support the needs of local commerce — especially in coinage-poor areas — and not on the management of funds. Their notes represented claims on the assets of the bank, which were typically a portfolio of real estate or marketable securities. At the time, the Democratic Party opposed any government involvement in banking, and Supreme Court rulings established that states could authorize currency issues only on the credit of private parties, not that of the state. Under these constraints, states turned to private actors to address money shortages. As different states passed free banking laws, entrepreneurs rushed to exploit their regulatory weaknesses.[7]

Before the establishment of the Federal Reserve System in 1913, banks issued their own bank notes to depositors that were redeemable in specie. The bank was obligated to pay these notes from cash reserves and, if reserves ran low, to raise more by selling outstanding investments. Failing even this, the state could redeem the notes on the value of a security deposit. The value of a bank's notes was determined by its ability to fulfill this obligation. Many of the states' regulations required for the banks to back their notes with state bonds. Banks in states that had safe bonds would thrive whereas banks in states that had risky bonds would suffer. Other factors could influence the value of a bank note, the major secondary cause being the likelihood of fraud, either from the bank or from forgery.[8]

Many varieties of money different banks traded at different discounts to their face value. Lists were published to help bankers and others to identify and appraise the bills (and forgeries). One of the major causes of discounting occurred due to the real cost of transferring the notes to the original bank, (Dennett 2016, English Provincial Paper Money).

Examples

- Bank of Florence

- Panic of 1837

In popular culture

In the Swedish movie The New Land (1972), the character Robert is paid in wildcat notes, which is later discovered by his brother Karl Oskar (about two hours into the movie).

See also

References

- Krause, Chester L.; Lemke, Robert F. (2003). Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money.

- Dunbar, William F. (1995). Michigan: A History of the Wolverine State. p. 223.

- Utley, H. M. (1884), "The Wild Cat Banking System of Michigan", Pioneer Collections, 5

- Sumner, William Graham (1896). A History of Banking in the United States.

- Catskill Bank $5 Contemporary Counterfeit

- White, Horace (1895). Money and Banking. p. 372.

- Conant, Charles A. (1915). A History of Modern Banks of Issue (5th ed.). pp. 373–379.

- Dwyer, Gerald P. "Wildcat Banking, Banking Panics, and Free Banking in the United States". Economic Review, 1996. p. 2. Retrieved 6 December 2013. "Free banks did not always redeem their notes as promised, and there are fabulous stories of fraudulent activities, stories that appear frequently in histories of free banking and general histories of banking."

Further reading

- Allen, Larry (2009). The Encyclopedia of Money (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 436–437. ISBN 978-1598842517.

External links

- U.S. banks and money Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

- "Wildcat bank". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. Retrieved 6 December 2013.