Wood Badge

Wood Badge is a Scouting leadership programme and the related award for adult leaders in the programmes of Scout associations throughout the world. Wood Badge courses aim to make Scouters better leaders by teaching advanced leadership skills, and by creating a bond and commitment to the Scout movement. Courses generally have a combined classroom and practical outdoors-based phase followed by a Wood Badge ticket, also known as the project phase. By "working the ticket", participants put their newly gained experience into practice to attain ticket goals aiding the Scouting movement. The first Wood Badge training was organized by Francis "Skipper" Gidney and lectured at by Robert Baden-Powell and others at Gilwell Park (United Kingdom) in September 1919. Wood Badge training has since spread across the world with international variations.

| Wood Badge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Wood Badge beads on top of the 1st Gilwell Scout Group neckerchief. | |||

| Country | All | ||

| Founded | 1919 | ||

| Founder | Baden-Powell | ||

| Awarded for | Completion of leadership training | ||

| Membership | > 100,000 | ||

|

| |||

On completion of the course, participants are awarded the Wood Badge beads to recognize significant achievement in leadership and direct service to young people. The pair of small wooden beads, one on each end of a leather thong (string), is worn around the neck as part of the Scout uniform. The beads are presented together with a taupe neckerchief bearing a tartan patch of the Maclaren clan, honoring William de Bois Maclaren, who donated the £7000 to purchase Gilwell Park in 1919 plus an additional £3000 for improvements to the house that was on the estate. The neckerchief with the braided leather woggle (neckerchief slide) denotes the membership of the 1st Gilwell Scout Group or Gilwell Troop 1. Recipients of the Wood Badge are known as Wood Badgers or Gilwellians.

Scout leader training course

History

Soon after founding the Scout movement, Robert Baden-Powell saw the need for leader training. Early Scoutmaster training camps were held in London and Yorkshire. Baden-Powell wanted practical training in the outdoors in campsites. World War I delayed the development of leader training, so the first formal Wood Badge course was not offered until 1919.[1][2][3] Gilwell Park, just outside London, was purchased specifically to provide a venue for the course and the Opening Ceremonies were held on July 26, 1919. Francis Gidney, the first Camp Chief at Gilwell Park, conducted the first Wood Badge course there from September 8–19, 1919. It was produced by Percy Everett, the Commissioner of Training, and Baden-Powell himself gave lectures. The course was attended by 18 participants, and other lecturers. After this first course, Wood Badge training continued at Gilwell Park, and it became the home of leadership training in the Scout movement.[4]

Modern curriculum

The main goals of a Wood Badge course are to:[5][6][7]

- Recognize the contemporary leadership concepts utilized in the corporate world and leading governmental organizations that are relevant to Scouting's values.

- Apply the skills one learns from participating as a member of a successful working team.

- View Scouting globally, as a family of interrelated, values-based programmes that provide age-appropriate activities for youth.

- Revitalize the leader's commitment by sharing in an inspirational experience that helps provide Scouting with the leadership it needs to accomplish its mission.

Generally, a Wood Badge course consists of classroom work, a series of self-study modules, outdoor training, and the Wood Badge "ticket" or "project". Classroom and outdoor training are often combined and taught together, and occur over one or more weeks or weekends. As part of completing this portion of the course, participants must write their tickets.

The exact curriculum varies from country to country, but the training generally includes both theoretical and experiential learning. All course participants are introduced to the 1st Gilwell Scout group or Gilwell Scout Troop 1 (the latter name is used in the Boy Scouts of America and some other countries). In the Boy Scouts of America, they are also assigned to one of the traditional Wood Badge "critter" patrols. Instructors deliver training designed to strengthen the patrols. One-on-one work with an assigned troop guide helps each participant to reflect on what he has learned, so that he can better prepare an individualized "ticket". This part of the training program gives the adult Scouter the opportunity to assume the role of a Scout joining the original "model" troop, to learn firsthand how a troop ideally operates. The locale of all initial training is referred to as Gilwell Field, no matter its geographical location.[8]

Ticket

The phrase 'working your ticket' comes from a story attributed in Scouting legend to Baden-Powell: Upon completion of a British soldier's service in India, he had to pay the cost of his ticket home. The most affordable way for a soldier to return was to engineer a progression of assignments that were successively closer to home.

Part of the transformative power of the Wood Badge experience is the effective use of metaphor and tradition to reach both heart and mind. In most Scout associations, "working your ticket" is the culmination of Wood Badge training. Participants apply themselves and their new knowledge and skills to the completion of items designed to strengthen the individual's leadership and the home unit's organizational resilience in a project or "ticket". The ticket consists of specific goals that must be accomplished within a specified time, often 18 months due to the large amount of work involved. Effective tickets require much planning and are approved by the Wood Badge course staff before the course phase ends. Upon completion of the ticket, a participant is said to have earned his way back to Gilwell.[9]

On completion

After completion of the Wood Badge course, participants are awarded the insignia in a Wood Badge bead ceremony.[10] They receive automatic membership in 1st Gilwell Park Scout Group or Gilwell Troop 1. These leaders are henceforth called Gilwellians or Wood Badgers. It is estimated that worldwide over 100,000 Scouters have completed their Wood Badge training.[11] The 1st Gilwell Scout Group meets annually during the first weekend in September at Gilwell Park for the Gilwell Reunion.[12] Gilwell Reunions are also held in other places, often on that same weekend.

Insignia

Scout leaders who complete the Wood Badge program are recognized with insignia consisting of the Wood Badge beads, 1st Gilwell Group neckerchief and woggle.

Woggle

The Gilwell woggle is a two-strand version of a Turk's head knot, which has no beginning and no end, and symbolizes the commitment of a Wood Badger to Scouting.[2][3] In some countries, Wood Badge training is divided into more than one part and the Gilwell woggle is given for completion of Wood Badge Part I.

Beads

The beads were first presented at the initial leadership course in September 1919 at Gilwell Park.

The origins of Wood Badge beads can be traced back to 1888, when Baden-Powell was on a military campaign in Zululand (now part of South Africa). He pursued Dinuzulu, son of Cetshwayo, a Zulu king, for some time, but never managed to catch up with him. Dinuzulu was said to have had a 12-foot (4 m)-long necklace with more than a thousand acacia beads.[13] Baden-Powell is claimed to have found the necklace when he came to Dinuzulu's deserted mountain stronghold.[3][14] Such necklaces were known as iziQu in Zulu and were presented to brave warrior leaders.[15]

Much later, Baden-Powell sought a distinctive award for the participants in the first Gilwell course. He constructed the first award using two beads from the necklace he had recovered, and threaded them onto a leather thong given to him by an elderly South African in Mafeking, calling it the Wood Badge.[1][2][3]

While no official knot exists for tying the two ends of the thong together, the decorative diamond knot has become the most common. When produced, the thong is joined by a simple overhand knot and various region specific traditions have arisen around tying the diamond knot, including: having a fellow course member tie it; having a mentor or course leader tie it; and having the recipient tie it after completing some additional activity that shows he or she has mastered the skills taught to him or her during training.[3]

Significance of additional beads

Additional beads are awarded to Wood Badgers who serve as part of a Wood Badge training team. One additional bead is awarded to each Assistant Leader Trainer (Wood Badge or NYLT staff) and two additional beads are awarded to each Leader Trainer (Wood Badge or NYLT course directors), for a total of four.[3]

As part of a tradition, five beads may be worn by the "Deputy Camp Chiefs of Gilwell". The Deputy Camp Chiefs are usually the personnel of National Scout Associations in charge of Wood Badge training. The fifth bead symbolizes the Camp Chief's position as an official representative of Gilwell Park, and his or her function in maintaining the global integrity of Wood Badge training.[3] William Hillcourt is one person who wore five beads.

The founder of the Scouting movement, Robert Baden-Powell, wore six beads, as did Sir Percy Everett, then Deputy Chief Scout and the Chief's right hand. Baden-Powell's beads are on display at Baden-Powell House in London. Everett endowed his six beads to be worn by the Camp Chief of Gilwell as a badge of office. Since that time the wearer of the sixth bead has generally been the director of leader training at Gilwell Park.[3]

| Number of beads | Worn by |

|---|---|

| 2 | Wood Badge recipient |

| 3 | Deputy Gilwell Course Leader |

| 4 | Gilwell Course Leader |

| 5 | Deputy Camp Chief of Gilwell Park, National Training Commissioner (one per country) |

| 6 | Camp Chief of Gilwell Park; Chief Scout of the World |

1st Gilwell Scout Group neckerchief

The neckerchief is a universal symbol of Scouting and its Maclaren tartan represents Wood Badge's ties to Gilwell Park. The neckerchief, called a "necker" in British and some Commonwealth Scouting associations, is a standard triangular scarf made of cotton or wool twill with a taupe face and red back; a patch of Clan MacLaren tartan is affixed near the point.[16] The pattern was adopted in honor of a British Scout commissioner who, as a descendant of the Scottish MacLaren clan, donated money for the Gilwell Park property on which the first Wood Badge program was held.[3][13][17]

Originally, the neckerchief was made entirely of triangular pieces of the tartan, but its expense forced the adoption of the current design. The neckerchief is often worn with the Gilwell woggle.[2][3]

Axe and Log

The axe and log logo was conceived by the first Camp Chief, Francis Gidney, in the early 1920s to distinguish Gilwell Park from the Scout Headquarters. Gidney wanted to associate Gilwell Park with the outdoors and Scoutcraft rather than the business or administrative Headquarters offices. Scouters present at the original Wood Badge courses regularly saw axe blades masked for safety by being buried in a log. Seeing this, Gidney chose the axe and log as the totem of Gilwell Park.[18]

Other symbols

The kudu horn is another Wood Badge symbol. Baden-Powell first encountered the kudu horn at the Battle of Shangani, where he discovered how the Matabele warriors used it to quickly spread a signal of alarm. He used the horn at the first Scout encampment at Brownsea Island in 1907. It is used from the early Wood Badge courses to signal the beginning of the course or an activity, and to inspire Scouters to always do better.

The grass fields at the back of the White House at Gilwell Park are known as the Training Ground and The Orchard, and are where Wood Badge training was held from the early years onward. A large oak, known as the Gilwell Oak, separates the two fields. The Gilwell Oak symbol is associated with Wood Badge, although the beads for the Wood Badge have never been made of this oak.[12]

Wolf Cub leaders briefly followed a separate training system beginning in 1922, in which they were awarded the Akela Badge on completion. The badge was a single fang on a leather thong. Wolf Cub Leader Trainers wore two fangs.[13][19] The Akela Badge was discontinued in 1925, and all leaders were awarded the Wood Badge on completion of their training. Very few of the fangs issued as Akela Badges can now be found.[3]

International training centers and trainers

Australia

Other sites providing Wood Badge training have taken the Gilwell name. The first Australian Wood Badge courses were held in 1920 after the return of two newly minted Deputy Camp Chiefs, Charles Hoadley and Mr. Russell at the home of Victorian Scouting, Gilwell Park, Gembrook. In 2003, Scouts Australia established the Scouts Australia Institute of Training, a government-registered National Vocational & Education Training (VET) provider. Under this registration, Scouts Australia awards a "Diploma of Leadership and Management" to those Adult Leaders who complete the Wood Badge training and additional competencies.[20] The Diploma of Leadership and Management, like all Australian VET qualifications, is recognized throughout Australia by both government and private industry.[21] This is an optional extra that Leaders and Rovers may undertake.

Austria

The first Wood Badge Training in Austria took place in 1932. Scoutmaster Joesef Miegl took his Wood Badge training in Gilwell Park and September 8 to 17, 1922, he led a Leader Training near Vienna, one of the first in Austria. Scouters from Austria, Germany, Italy and Hungary took part. He brought in many things he learned in Gilwell Park about International and British Scouting, but it was not an official Wood Badge training.[22]

Belgium

The first Wood Badge training in Belgium was held in August 1923 at Jannée, led by Étienne Van Hoof.

Canada

Scouts Canada holds numerous Wood Badge training courses on an annual basis throughout the country. In this NSO, all Scouters (volunteers) are required to complete an online Wood Badge Part I Course,[23] and are encouraged to complete a Wood Badge Part II program that includes self-directed learning, conducted through mentorship and coaching in addition to traditional courses and workshops.[24] Upon completion of the Woodbadge Part II[25] program a volunteer is conferred their "beads" and the Gilwell Necker.

Finland

Alfons Åkerman gave the first eight Wood Badge courses and was from 1927 to 1935 the first Deputy Camp Chief. In lieu of Gilwell training, the Finnish Scouts have a "Kolmiapila-Gilwell" (Trefoil-Gilwell), combining aspects of both girls' and boys' advanced leadership training.[26]

France

The first Wood Badge training in France was held Easter 1923 by Père Sevin in Chamarande.[27]

Ireland

Wood Badge training in Ireland goes back to the 1st Larch Hill of the Catholic Boy Scouts of Ireland, who conducted Wood Badge courses that emphasized the Catholic approach to Scouting. This emphasis is now disappeared since the formation of Scouting Ireland.[28]

Israel

The first Wood Badge training in Israel was held in April 1963 by John Thurman and took place at the Israeli Scout Ranch, together with 20 participants, Jews, Arabs and Druze. Since the first training, every Wood Badge course run by the Israel Boy and Girl Scouts Federation is a mutual event for all different religions and organizations in Scouting.

Hungary

In 2010, 21 year after the reorganization of Hungarian Scout Association, was the first Scoutmaster training with the Wood Badge. (There was other Scoutmaster training before, but these weren't organized according to the Wood Badge Framework.) The head of the first Wood Badge training in Hungary was Balázs Solymosi who has four beads. From 2010 to 2018, in 8 courses more than 50 adult leader performed successfully and awarded. In 2019 started a new era in Wood Badge training in Hungary. Two type of courses are available: one for leaders in the Association and one for local group leaders. The association level have the basis made by Balázs Solymosi, the group leader level based on a new training program. Both program gives the highest level of scouting knowledge from different point of view for the participants.[29]

The Netherlands

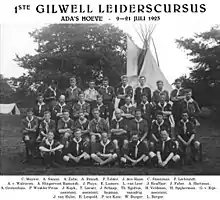

The first Wood Badge training in the Netherlands was held in July 1923 by Scoutmaster Jan Schaap, on Gilwell Ada's Hoeve, Ommen. At Gilwell Sint Walrick, Overasselt, the Catholic Scouts had their training. Since approximately 2000, the Dutch Wood Badge training takes place on the Scout campsite Buitenzorg, Baarn, or outdoors in Belgium or Germany under the name 'Gilwell Training'.[30]

Norway

In Norway, Woodbadge is known as Trefoil-Gilwell Training.[31]

Philippines

Wood Badge was introduced in the Philippines in 1953 with the first course held at Camp Gre-Zar in Novaliches, Quezon City. Today, Wood Badge courses are held at the Philippine Scouting Center for the Asia-Pacific Region, at the foothills of Mount Makiling, Los Baños, Laguna province.[32]

Sweden

As in several other Nordic countries, the Swedish Wood Badge training is known as Trefoil Gilwell, being a unification of the former higher leadership programmes of the Swedish Guides and Scouts, known respectively as the Trefoil training and the Gilwell training.[33]

United Kingdom

The first Wood Badge training took place on Gilwell Park. The estate continues to provide the service in 2007, for British Scouters of The Scout Association and international participants. Original trainers include Baden-Powell and Gilwell Camp Chiefs Francis Gidney, John Wilson and, until the 1960s, John Thurman.[34]

United States

Wood Badge was introduced to America by Baden-Powell and the first course was held in 1936 at the Mortimer L. Schiff Scout Reservation, the Boy Scouts of America national training center until 1979.[35] Despite this early first course, Wood Badge was not formally adopted in the United States until 1948 under the guidance of Bill Hillcourt who became national Deputy Camp Chief of the United States.[36] Today the national training center of the Boy Scouts of America is the Philmont Training Center, which hosts a few camps each year. Nearly all Wood Badge courses are held throughout the country at local council camps under the auspices of each BSA region. [37]

References

- Block, Nelson R. (1994). "The Founding of Wood Badge". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2006.

- Orans, Lewis P. (2004). "The Wood Badge Homepage". Pinetree Web. Archived from the original on August 3, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2006.

- "The Origins of the Wood Badge" (PDF). ScoutBase UK. 2003. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- "The Wood Badge Homepage". Pinetree Web. Archived from the original on August 3, 2006. Retrieved August 1, 2006.

- "Rule 3.34: Adult Training Obligations". Policy, Organisation and Rules. The Scout Association. Archived from the original on October 31, 2007. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- Barnard, Mike (2002). "The Objectives of Wood Badge". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- "Training: The Wood Badge". CATVOG Scout Area (The Scout Association). Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- Wood Badge for the 21st Century – Staff Guide. Boy Scouts of America. 2001.

- Barnard, Mike (2003). "What is a Wood Badge Ticket?". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- Barnard, Mike (2002). "Wood Badge Presentation Ceremonies". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- "History of Wood Badge". Green Mountain Council Boy Scouts of America. 2007. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- Rogers, Peter (1998). Gilwell Park: A Brief History and Guided Tour. London, England: The Scout Association. pp. 5–46.

- "The origins of the Wood Badge". Johnny Walker's Scouting Milestones. 2006. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- Hillcourt, William (1964). Baden-Powell: The Two Lives of a Hero. London: Heinemann. p. 358.

- "iziQu". African History. About.com. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- "Clan MacLaren and the Scouting Connection". Clan Maclaren.org. 2004. Archived from the original on July 26, 2007. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- "History of Wood Badge". Scouting.org. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- Block, Nelson; Larson, Keith (October–November 1994). "Origins of the Wood Badge Axe". Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- "The history of Cubbing in the United Kingdom 1916–present". ScoutBase UK. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- "Wood Badge Training Program". Scouts Australia. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- "Training Bulletin: Woodbadge holders" (PDF). Scouts Australia. August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2007.

- "Symposium of World-wide Scouting". Jamboree: Journal of World Scouting. 9: 137. January 1923.

- "Wood Badge I - FAQ". Scouts Canada. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "Learning and Development". Scouts Canada. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "Wood Badge II". Scouts Canada. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- "History". Partio Scout. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Chamarande". Honneur au Scoutisme (in French). Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Resources: Adult Resources". Scouting Ireland. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2007.

- A cserkésztiszti vezetőképzés emlékezetője. Budapest: Magyar Cserkészszövetség. 2015. ISBN 9789638305411.

- "Cursusvarianten". Gilwell een wereldcurcus (in Dutch). Scouting Nederland. Archived from the original on March 10, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- "Trekløver-Gilwell - Norges speiderforbund". speiding.no. March 9, 2017.

- Diamond Jubilee Yearbook. Manila: Boy Scouts of the Philippines. 1996. ISBN 9789719176909.

- "Treklöver Gilwell - Scouternas folkhögskola" (in Swedish). Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Walker, Johnny (2006). "Gidney, Francis 'Skipper'. 1890–1928". Scouting Personalities. Johnny Walker's Scouting Milestones. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

- Barnard, Mike (2002). "History of Wood Badge in the United States". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2007.

- Barnard, Mike (2001). "Green Bar Bill Hillcourt's Impact on Wood Badge". Woodbadge.org. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 30, 2007.

- "Take Wood Badge at Philmont". Philmont Training Center. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wood badge. |