Xenharmonic music

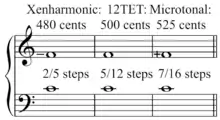

Xenharmonic music is that which uses a tuning system which neither conforms to nor closely approximates the common 12-tone equal temperament. The term xenharmonic was coined by Ivor Darreg, from xenia (Greek ξενία), "hospitable," and xenos (Greek ξένος) "foreign." He stated it as being "intended to include just intonation and such temperaments as the 5-, 7-, and 11-tone, along with the higher-numbered really-microtonal systems as far as one wishes to go."[1]

John Chalmers, author of Divisions of the Tetrachord, writes: "The converse of this definition is that music which can be performed in 12-tone equal temperament without significant loss of its identity is not truly microtonal."[2] Thus xenharmonic music may be distinguished from the more common twelve-tone equal temperament, as well as some use of just intonation and equal temperaments, by the use of unfamiliar intervals, harmonies, and timbres.

Theorists other than Chalmers consider xenharmonic and non-xenharmonic to be subjective. As an example, Edward Foote, in his program notes for his "6 degrees of tonality" CD, refers to the differences in his response to the more radical tunings he uses, such as Kirnberger and DeMorgan, from "shocking", to "Too subtle to immediately notice", saying:

Temperaments are new territory for 20th century ears. The first-time listener may find it shocking to hear the harmony change "color" during modulations or too subtle to immediately notice[3]

Diatonic xenharmonic music

Music also can share much of the familiar territory of twelve tone music and yet have xenharmonic features. As examples, Easley Blackwood, author of The Structure of Recognizable Diatonic Tunings (1985), wrote many etudes in ETs from 12 equal to 24 equal which bring out both many connections and resemblances to twelve tone music as well as bringing out various xenharmonic characteristics of the tunings. See his Twelve Microtonal Etudes for Electronic Music Media.

In his program notes for his Fanfare in 19-et,[4] he writes:

...Triads are smooth, but the scale sounds slightly out of tune because the leading tone seems low with respect to the tonic. Diatonic behavior is virtually identical to that of 12-note tuning, but chromatic behavior is very different. For example, a perfect fourth is divisible into two equal parts, while an augmented sixth and a diminished seventh sound identical. ... The development modulates entirely around the circle of nineteen fifths.

For a perhaps more radical example, for his sixteen notes Andantino,[4] he writes:

This tuning is best thought of as a combination of four intertwined diminished seventh chords. Since 12-note tuning can be regarded as a combination of three diminished seventh chords, it is plain that the two tunings have elements in common. The most obvious difference in the way the two tunings sound and work is that triads in 16-note tuning, although recognizable, are too discordant to serve as the final harmony in cadences. Keys can still be established by successions of altered subdominant and dominant harmonies, however, and the Etude is based mainly upon this property. The fundamental consonant harmony employed is a minor triad with an added minor seventh.

Darreg explains: "I devised the term 'xenharmonic' to refer to everything that does not sound like 12-tone equal temperament."[5]

Tunings, instruments, and composers

Any scale or tuning other than 12-tone equal temperament can be used to create xenharmonic music. This includes other equal divisions of the octave and scales based on extended just intonation.

Tunings derived from the partials or overtones of physical objects with an inharmonic spectrum or overtone series such as rods, prongs, plates, discs, spheroids and rocks are sometimes used as the basis of xenharmonic exploration. William Sethares is a pioneer in this area. William Colvig, who worked with the composer Lou Harrison created the tubulong, a set of xenharmonic tubes.[6]

Electronic music composed with arbitrarily chosen xenharmonic scales was explored on the album Radionics Radio: An Album of Musical Radionic Thought Frequencies (2016) by British composer Daniel Wilson, who composed his pieces with frequency-runs submitted by users of a custom-built web application replicating radionics-based electronic soundmaking equipment used by Oxford's De La Warr Laboratories in the late 1940s.[7]

The Non-Pythagorean scale utilized by Robert Schneider of The Apples in Stereo, based on a sequence of logarithms, may be considered xenharmonic, as well as Annie Gosfield's purposefully "out of tune" sampler based music using non systematic tunings and the work of other composers including Elodie Lauten, Wendy Carlos, Ivor Darreg, Paul Erlich and many others.

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved January 13, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Chalmers, John H. (1993). Divisions of the tetrachord: a prolegomenon to the construction of musical scales, p.1. Frog Peak Music. ISBN 9780945996040.

- Foote, Edward (2001). "Six Degrees Of Tonality The Well Tempered Piano - CD notes". UK piano page.

- Blackwood, Easley. "Blackwood: Microtonal Compositions".

- Robert Smith, Robert Wilhite. Sound: An Exhibition of Sound Sculpture, Instrument Building and Acoustically Tuned Spaces : Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, July 14-August 31, 1979, Project Studios 1, New York, September 30-November 18, 1979.

- Haluška, Ján (2003). The Mathematical Theory of Tone Systems, p.284. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 9788088683285.

- Wilson, Daniel (2016). "Radionics in Relation to Acoustics (CD notes in Radionics Radio: An Album of Musical Radionic Thought Frequencies)". Sub Rosa.

Further reading

- Sethares, William (2004) Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale. ISBN 3-540-76173-X.

External links

- Microtonality - Web (in Spanish)

- Microtonal music on CD

- Homepage for William Sethares

- The Xenharmonic Wiki, formerly at Wikispaces

- Xenharmonic Alliance

- Barbieri, Patrizio. Enharmonic instruments and music, 1470-1900. (2008) Latina, Il Levante Libreria Editrice

- Blackwood Microtonal Compositions Easley Blackwood & Jeffrey Kust, on iTunes Includes Fanfare in 19-EDO. Also includes the 16 notes Andantino as the first of the twelve etudes in that collection.

- microtonal piano work of Noah Jordan