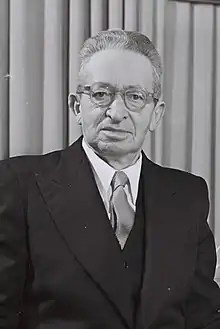

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (Hebrew: יִצְחָק בֶּן־צְבִי Yitshak Ben-Tsvi; 24 November 1884 – 23 April 1963) was a historian, Labor Zionist leader and the longest-serving President of Israel.

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi יצחק בן־צבי | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd President of Israel | |

| In office 16 December 1952 – 23 April 1963 | |

| Prime Minister | David Ben-Gurion Moshe Sharett David Ben-Gurion |

| Preceded by | Chaim Weizmann |

| Succeeded by | Zalman Shazar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 November 1884 Poltava, Russian Empire |

| Died | 23 April 1963 (aged 78) Jerusalem, Israel |

| Nationality | Israeli |

| Political party | Mapai |

| Spouse(s) | Rachel Yanait |

| Children | 2 |

| Alma mater | Istanbul University Faculty of Law |

| Signature |  |

Biography

Born in Poltava in the Russian Empire (today in Ukraine), Ben-Zvi was the eldest son of Zvi Shimshelevich, who later took the name Shimshi. Shimshi was a leading Zionist activist and one of the organizers of the first Zionist Congress in 1897, who in 1952 was honored by the first Israeli Knesset with the title "Father of the State of Israel". A member of the B'ne Moshe and Hoveve Zion movements in Ukraine, he was (with Theodore Herzl) one of the organizers of the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in the fall of 1897. At that Congress the World Zionist Organization was founded, and the intention to re-establish a Jewish state was announced. Shimshi was the only organizer of the first Zionist Congress to live to see the birth of the modern State of Israel in 1948. On 10 December 1952, Zvi Shimshi was honored by the first Israeli Knesset (parliament) with the title "Father of the State of Israel".

Ben-Zvi's brother was author Aharon Reuveni, and his brother-in-law was the Israeli archaeologist Benjamin Mazar.[1]

Ben Zvi had a formal Jewish education at a Poltava heder and then the local Gymnasium. He completed his first year at Kiev University studying natural sciences before dropping out to dedicate himself to the newly formed Russian Poale Zion which he co-founded with Ber Borochov.

In 1910, Ben-Zvi, Rachel Yana'it and Ze'ev Ashur founded Ahdut, the first Hebrew socialist periodical.

Following his studies at Galatasaray High School in Istanbul, Ben-Zvi studied law at Istanbul University from 1912 to 1914, together with the future Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion. They returned to Palestine in August 1914, but were expelled by the Ottoman authorities in 1915. The two of them moved to New York City, where they engaged in Zionist activities and founded the HeHalutz (Pioneer) movement there. Together, they also wrote the Yiddish book The Land of Israel: Past and Present to promote the Zionist cause among American Jewry.

Upon returning to Palestine in 1918, Ben-Zvi married Yanait. They had two sons: Amram and Eli. Eli died in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, defending his kibbutz, Beit Keshet.

Zionist activism

Following Borochov's arrest, March 1906, and subsequence exile in America, Ben Zvi became leader of the Russian Poale Zion. He moved their headquarters from Poltava to Vilna and established a publishing house, the Hammer, which produced the party's paper, The Proletarian Idea. In April 1907, having been arrested twice and being under surveillance by the Tzarist secret police, Ben-Zvi made Aliyah. He traveled on forged papers. It was his second visit to Palestine. On his arrival in Jaffa he changed his name to Ben Zvi - Son of Zvi. He found the local Poale Zion divided and in disarray. Slightly older and more experienced than his comrades he took command and, the following month, organised a gathering of around 80 members. He and a Rostovian - a strict Marxist group from Rostov - were elected as the new Central Committee. Two of the party's founding principles were reversed : Yiddish, not Hebrew was to be the language used and the Jewish and the Arab proletariat should unite. It was agreed to publish a party journal in Yiddish - Der Anfang. The conference also voted that Ben Zvi and Israel Shochat should attend the 8th World Zionist Congress in The Hague. Once there they were generally ignored. They ran out of money on their return journey and had to work as porters in Trieste. Back in Jaffa they held another gathering, 28th September 1907, to report on the Hague conference. On the first evening of the conference a group of nine men met in Ben Zvi's room where , swearing themselves to secrecy with Shochat as their leader, they agreed to set up an underground military organisation - Bar-Giora, named after Simon Bar Giora. It's slogan was: " Judea fell in blood and fire; Judea shall rise again in blood and fire.".Ben Gurion was not invited to join and it had been his policies which were overturned in April. Despite this Ben Zvi tried unsuccessfully to invite Ben Gurion onto the Central Committee.[2]

Ben-Zvi served in the Jewish Legion (1st Judean battalion 'KADIMAH') together with Ben-Gurion. He helped found the Ahdut HaAvoda party in 1919, and became increasingly active in the Haganah. According to Avraham Tehomi, Ben-Zvi ordered the 1924 murder of Jacob Israël de Haan.[3] De Haan had come to Palestine as an ardent Zionist, but he had become increasingly critical of the Zionist organizations, preferring a negotiated solution to the armed struggle between the Jews and Arabs. This is how Tehomi acknowledged his own part in the murder over sixty years later, in an Israeli television interview in 1985: "I have done what the Haganah decided had to be done. And nothing was done without the order of Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. I have no regrets because he [de Haan] wanted to destroy our whole idea of Zionism."[3]

Political career

Ben Zvi was elected to the Jerusalem City Council and by 1931 served as president of the Jewish National Council, the shadow government of the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine. When Israel gained its independence, Ben-Zvi was among the signers of its Declaration of Independence on 14 May 1948. He served in the First and Second Knessets for the Mapai party. In 1951, Ben-Zvi was appointed one of the acting members of the Government Naming Committee, whose duty was to decide on appropriate names for newly constructed settlements.[4]

Pedagogic and research career

In Jaffa Ben Zvi found work as a teacher. In 1909, he organized the Gymnasia Rehavia high school in the Bukharim quarter of Jerusalem together with Rachel Yanait.

In 1948, Ben-Zvi headed the Institute for the Study of Oriental Jewish Communities in the Middle East, later named the Ben-Zvi Institute (Yad Ben-Zvi) in his honor. The Ben-Zvi Institute occupies Nissim Valero's house.[5] His main field of research was the Jewish communities and sects of Asia and Africa, including the Samaritans and Karaites.

Presidency

He was elected President of Israel on 8 December 1952, assumed office on 16 December 1952, and continued to serve in the position until his death.

Ben-Zvi believed that the president should set an example for the public, and that his home should reflect the austerity of the times. For over 26 years, he and his family lived in a wooden hut in the Rehavia neighborhood of Jerusalem. The State of Israel took interest in the adjacent house, built and owned by Nissim and Esther Valero, and purchased it, after Nissim's death, to provide additional space for the President's residence.[6] Two larger wooden structures in the yard were used for official receptions.

Awards and recognition

In 1953, Ben-Zvi was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.[7]

Ben-Zvi's photo appears on 100 NIS bills. Many streets and boulevards in Israel are named for him. In 2008, Ben-Zvi's wooden hut was moved to Kibbutz Beit Keshet, which his son helped to found, and the interior was restored with its original furnishings. The Valero house in Rehavia neighbourhood was designated an historic building protected by law under municipal plan 2007 for the preservation of historic sites.[8]

Published works

- Coming Home, translated from Hebrew by David Harris and Julian Metzer, Tel Aviv, 1963

- Derakhai Siparti, (Jerusalem, 1971)

Gallery

Rabbi Moshe Gabai petitioning President Zvi to help the Jewish community in Zacho, Iraq, 1951

Rabbi Moshe Gabai petitioning President Zvi to help the Jewish community in Zacho, Iraq, 1951 100 Israeli new shekel bill

100 Israeli new shekel bill

See also

References

- Dan Mazar (1994) Jerusalem Christian Review

- Teveth, Shabtai (1987) Ben-Gurion. The Burning Ground. 1886-1948. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-35409-9. pp. 51-55

- Shlomo Nakdimon; Shaul Mayzlish (1985). דה האן : הרצח הפוליטי הראשון בארץ ישראל Deh Han : ha-retsah ha-politi ha-rishon be-Erets Yisraʼel / De Haan: The first political assassination in Israel (in Hebrew) (1st ed.). Tel Aviv: Modan Press. OCLC 21528172.

- "State of Israel Records", Collection of Publications, no. 152 (PDF) (in Hebrew), Jerusalem: Government of Israel, 1951, p. 845

- Ben Zvi Institute, 12 Abarbanel St., Jerusalem

- Eilat Gordin Levitan. "Shimshelevitz Family". Eilatgordinlevitan.com. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "List of Bialik Prize recipients 1933–2004 (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv Municipality website" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2007.

- Joseph B. Glass; Ruth Kark (2007). Sephardi entrepreneurs in Jerusalem: the Valero family 1800–1948. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-396-1. OCLC 191048781.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. |

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- English Online-catalog of the library of the Ben Zvi Institute

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/ben-zvi.html