Youth in India

Education

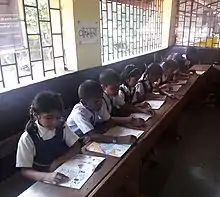

As per the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2012, 96.5% of all rural children between the ages of 6-14 were enrolled in school. This is the fourth annual survey to report enrollment above 96%. India has maintained an average enrolment ratio of 95% for students in this age group from year 2007 to 2014. As an outcome the number of students in the age group 6-14 who are not enrolled in school has come down to 2.8% in the year academic year 2018 (ASER 2018).[1] Another report from 2013 stated that there were 229 million students enrolled in different accredited urban and rural schools of India, from Class I to XII, representing an increase of 23 lakh students over 2002 total enrolment, and a 19% increase in girl's enrolment.[2] While quantitatively India is inching closer to universal education, the quality of its education has been questioned particularly in its government run school system.While more than 95 percent of children attend primary school, just 40 percent of Indian adolescents attend secondary school (Grades 9-12). Since 2000, the World Bank has committed over $2 billion to education in India. Some of the reasons for the poor quality include absence of around 25% of teachers every day.[3] States of India have introduced tests and education assessment system to identify and improve such schools.[4]

The primary education in India is divided into two parts, namely Lower Primary (Class I-IV) and Upper Primary (Middle school, Class V-VIII). The Indian government lays emphasis on primary education ( Class I-VIII ) also referred to as elementary education, to children aged 6 to 14 years old.[5] Because education laws are given by the states, duration of primary school visit alters between the Indian states. The Indian government has also banned child labour in order to ensure that the children do not enter unsafe working conditions.[5] However, both free education and the ban on child labour are difficult to enforce due to economic disparity and social conditions.[5] 80% of all recognised schools at the elementary stage are government run or supported, making it the largest provider of education in the country.[6]

However, due to a shortage of resources and lack of political will, this system suffers from massive gaps including high pupil to teacher ratios, shortage of infrastructure and poor levels of teacher training. Figures released by the Indian government in 2011 show that there were 5,816,673 elementary school teachers in India.[7] As of March 2012 there were 2,127,000 secondary school teachers in India.[8] Education has also been made free[5] for children for 6 to 14 years of age or up to class VIII under the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act 2009.[9]

The National Sample Survey Organisation and the National Family Health Survey collected data in India on the percentage of children completing primary school which are reported to be only 36.8% and 37.7% respectively.[10] On 21 February 2005, the Prime Minister of India said that he was pained to note that "only 47 out of 100 children enrolled in class I reach class VIII, putting the dropout rate at 52.78 percent."[11] It is estimated that at least 35 million, and possibly as many as 60 million, children aged 6–14 years are not in school.[12]

Nutrition

The World Bank estimates that India is one of the highest ranking countries in the world for the number of children suffering from malnutrition. The prevalence of underweight children in India is among the highest in the world, and is nearly double that of Sub Saharan Africa with dire consequences for mobility, mortality, productivity and economic growth.[13]

On the Global Hunger Index India is on place 67 among the 80 nations having the worst hunger situation which is worse than nations such as North Korea or Sudan. 25% of all hungry people worldwide live in India. Since 1990 there has been some improvements for children but the proportion of hungry in the population has increased. In India 44% of children under the age of 5 are underweight. 72% of infants and 52% of married women have anaemia. Research has conclusively shown that malnutrition during pregnancy causes the child to have increased risk of future diseases, physical retardation, and reduced cognitive abilities.[14]

Socio-economic status

When it comes to child malnutrition, children in low-income families are more malnourished than those in high-income families.PDS system in India which account for distribution of wheat and rice only,by which the proteins are insufficient by these cereals which leads to malnutrition also. Some cultural beliefs that may lead to malnutrition is religion. Among these is the influence of religions, especially in India are restricted from consuming meat. Also, other Indians are strictly vegan, which means, they do not consume any sort of animal product, including dairy and eggs. This is a serious problem when inadequate protein is consumed because 56% of poor Indian household consume cereal to consume protein. It is observed that the type of protein that cereal contains does not parallel to the proteins that animal product contain (Gulati, 2012).[15] This phenomenon is most prevalent in the rural areas of India where more malnutrition exists on an absolute level. Whether children are of the appropriate weight and height is highly dependent on the socio-economic status of the population.[16] Children of families with lower socio-economic standing are faced with sub-optimal growth. While children in similar communities have shown to share similar levels of nutrition, child nutrition is also differential from family to family depending on the mother's characteristic, household ethnicity and place of residence. It is expected that with improvements in socio-economic welfare, child nutrition will also improve.[17]

The rates of malnutrition are exceptionally high among adolescent girls and pregnant and lactating women in India, with repercussions for children's health.[lower-alpha 1][18]

Midday Meal Nutrition Scheme

The Midday Meal Scheme is a school meal programme of the Government of India designed to improve the nutritional status of school-age children nationwide,[19] by supplying free lunches on working days for children in primary and upper primary classes in government, government aided, local body, Education Guarantee Scheme, and alternative innovative education centres, Madarsa and Maqtabs supported under Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, and National Child Labour Project schools run by the ministry of labour.[20] Serving 120,000,000 children in over 1,265,000 schools and Education Guarantee Scheme centres, it is the largest such programme in the world.[21]

Street children

India has an estimated one hundred thousand or more street children in each of the following cities: New Delhi, Kolkata, and Mumbai.[22] Mainly because of family conflict, they come to live on the streets and take on the full responsibilities of caring for themselves, including working to provide for and protecting themselves. Though street children do sometimes band together for greater security, they are often exploited by employers and the police.[23][24]

Their many vulnerabilities require specific legislation and attention from the government and other organisations to improve their condition.[25]

Child marriage

Child marriage in India, according to the Indian law, is a marriage where either the woman is below the age of 18 or the man is below the age of 21. Most child marriages involve underage women, many of whom are in poor socio-economic conditions.

Child marriages are prevalent in India. Estimates vary widely between sources as to the extent and scale of child marriages. The International Center for Research on Women-UNICEF publications have estimated India's child marriage rate to be 47% from a sample surveys of 1998,[26] while the United Nations reports it to be 30% in 2005.[27] The Census of India has counted and reported married women by age, with proportion of females in child marriage falling in each 10 year census period since 1981. In its 2001 census report, India stated zero married girls below the age of 10, 1.4 million married girls out of 59.2 million girls aged 10–14, and 11.3 million married girls out of 46.3 million girls aged 15–19.[28] Times of India reported that 'since 2001, child marriage rates in India have fallen by 46% between 2005 and 2009.[29]Jharkhand is the state with highest child marriage rates in India (14.1%), while Kerala is the only state where child marriage rates have increased in recent years.[29][30] Jammu and Kashmir was reported to be the only state with lowest child marriage cases at 0.4% in 2009.[29] Rural rates of child marriages were three times higher than urban India rates in 2009.[29]

Child marriage was outlawed in 1929, under Indian law. However, in the British colonial times, the legal minimum age of marriage was set at 14 for girls and 18 for boys. Under protests from Muslim organizations in the undivided British India, a personal law Shariat Act was passed in 1937 that allowed child marriages with consent from girl's guardian.[31] After independence and adoption of Indian constitution in 1950, the child marriage act has undergone several revisions. The minimum legal age for marriage, since 1978, has been 18 for women and 21 for men. The child marriage prevention laws have been challenged in Indian courts,[31] with some Muslim Indian organizations seeking no minimum age and that the age matter be left to their personal law.[32][33] Child marriage is an active political subject as well as a subject of continuing cases under review in the highest courts of India.[32]

Several states of India have introduced incentives to delay marriages. For example, the state of Haryana introduced the so-called Apni Beti, Apna Dhan program in 1994, which translates to "My daughter, My wealth". It is a conditional cash transfer program dedicated to delaying young marriages by providing a government paid bond in her name, payable to her parents, in the amount of ₹25,000 (US$350), after her 18th birthday if she is not married.[34]

Child marriage has been traditionally prevalent in India but is not so continued in Modern India to this day. Historically, child brides would live with their parents until they reached puberty. In the past, child widows were condemned to a life of great agony, shaved heads, living in isolation, and being shunned by society.[35] Although child marriage was outlawed in 1860, it is still a common practice.[36] The Child Marriage Restraint Act, 1929 is the relevant legislation in the country.

According to UNICEF's "State of the World’s Children-2009" report, 47% of India's women aged 20–24 were married before the legal age of 18, rising to 56% in rural areas.[37] The report also showed that 40% of the world's child marriages occur in India.[38]

Sexual abuse

Laws

Child sexual abuse laws in India have been enacted as part of the child protection policies of India. The Parliament of India passed the 'Protection of Children Against Sexual Offences Bill, 2011' regarding child sexual abuse on 22 May 2012 into an Act.[39][40][41] The rules formulated by the government in accordance with the law have also been notified on the November 2012 and the law has become ready for implementation.[42] There have been many calls for more stringent laws.[43][44]

Child trafficking

India has one of the largest population of children in the world - Census data from 2011 shows that India has a population of 472 million children below the age of eighteen.[45][46] Protection of children by the state is guaranteed to Indian citizens by an expansive reading of Article 21[47] of the Indian constitution, and also mandated given India's status as signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

India has a very high volume of child trafficking. As many as one child disappears every eight minutes, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.[48] In some cases, children are taken from their homes to be bought and sold in the market. In other cases, children are tricked into the hands of traffickers by being presented an opportunity for a job, when in reality, upon arrival they become enslaved. In India, there are many children trafficked for various reasons such as labor, begging, and sexual exploitation. Because of the nature of this crime; it is hard to track; and due to the poor enforcement of laws, it is difficult to prevent.[49] Due to the nature of this crime, it is only possible to have estimates of figures regarding the issue. India is a prime area for child trafficking to occur, as many of those trafficked are from, travel through or destined to go to India. Though most of the trafficking occurs within the country, there is also a significant number of children trafficked from Nepal and Bangladesh.[50] There are many different causes that lead to child trafficking, with the primary reasons being poverty, weak law enforcement, and a lack of good quality public education. The traffickers that take advantage of children can be from another area in India, or could even know the child personally. Children who return home after being trafficked often face shame in their communities, rather than being welcomed home.[51]

See also

Notes

- "Reports of National Health & Family Survey, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, and WHO have highlighted that rates of malnutrition among adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and children are alarmingly high in India. Factors responsible for malnutrition in the country include mother’s nutritional status, lactation behaviour, women’s education, and sanitation. These affect children in several ways including stunting, childhood illness, and retarded growth."[18]

References

- ASER-2018 RURAL, Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) (PDF). India: ASER Centre. 2019. p. 47. ISBN 9789385203015.

- Enrollment in schools rises 14% to 23 crore The Times of India (22 January 2013)

- Sharath Jeevan & James Townsend, Teachers: A Solution to Education Reform in India Stanford Social Innovation Review (17 July 2013)

- B.P. Khandelwal, Examinations and test systems at school level in India UNESCO, pages 100-114

- Blackwell, 93–94

- https://web.archive.org/web/20081231235835/http://www.dise.in/ar2005.html. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2016. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "flashstatistics2009-10.pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Ministry of Human Resource Development (March 2012). "Report to the People on Education 2010-11" (PDF). New Delhi. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- Ministry of Law and Justice (Legislative Department) (27 August 2009). "The Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act" (PDF). Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2016.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Social Exclusion of Scheduled Caste Children from Primary Education in India" (PDF). Source: UNICEF. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Global campaign for education- more teachers needed". Source: UNICEF India. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "The Challenges for India's Education System" (PDF). Source: Chatham House. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

-

"World Bank Report". Source: The World Bank (2009). Retrieved 2009-03-13.

World Bank Report on Malnutrition in India

- Superpower? 230 million Indians go hungry daily, Subodh Varma, 15 Jan 2012, The Times of India,

- Gulati, A., Ganesh-Kumar, A., Shreedhar, G., & Nandakumar, T. (2012). Agriculture and malnutrition in India. Food And Nutrition Bulletin, 33(1), 74–86

- "HUNGaMA Survey Report" (PDF). Naandi foundation. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Kanjilal, Barun; Mazumdar; Mukherjee; Rahman (January 2010). "Nutritional status of children in India: household socio-economic condition as the contextual determinant". International Journal for Equity in Health. 9: 19–31. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-9-19. PMC 2931515. PMID 20701758.

- Narayan, Jitendra; John, Denny; Ramadas, Nirupama (2018). "Malnutrition in India: status and government initiatives". Journal of Public Health Policy. 40 (1): 126–141. doi:10.1057/s41271-018-0149-5. ISSN 0197-5897. PMID 30353132. S2CID 53032234.

- Chettiparambil-Rajan, Angelique (July 2007). "India: A Desk Review of the Mid-Day Meals Programme" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- "Frequently Asked Questions on Mid Day Meal Scheme" (PDF). Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- "About the Mid Day Meal Scheme". Mdm.nic.in. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Poonam R. Naik, Seema S. Bansode, Ratnenedra R. Shinde & Abhay S. Nirgude (2011). "Street children of Mumbai: demographic profile and substance abuse". Biomedical Research. 22 (4): 495–498.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chatterjee, A. (1992). "India: The forgotten children of the cities". Florence, Italy: Unicef. Retrieved February 20, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bose, A.B. (1992). "The Disadvantaged Urban Child in India". Innocenti Occasional Papers, Urban Child Series. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- Thomas de Benítez, Sarah (2007). "State of the world's street children". Consortium for Street Children. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- "Child Marriage Facts and Figures".

- "United Nations Statistics Division - Demographic and Social Statistics".

- .Table C-2 Marital Status by Age and Sex Subtable C0402, India Total Females Married by Age Group, 2001 Census of India, Government of India (2009)

- K. Sinha Nearly 50% fall in brides married below 18 The Times of India (February 10, 2012)

- R Gopakumar, Child marriages high in Kerala Deccan Herald (June 19, 2013)

- Hilary Amster, Child marriage in India Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine University of San Francisco (2009)

- M.G. Radhakrishnan and J. Binduraj, In a league of their own India Today (July 5, 2013)

- Muzaffar Ali Sajjad And Ors. vs State Of Andhra Pradesh on 9 November, 2001 Andhra Pradesh High Court, India

- "Child Marriage Facts and Figures". International Center for Research on Women.

- Kamat, Jyotsana (19 December 2006). "Gandhi and status of women (blog)". kamat.com. Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 24 December 2006.

- Lawson, Alastair (24 October 2001). "Child marriages targeted in India". BBC News.

- UNICEF (2009). "Table 9: Child protection". In UNICEF (ed.). The state of the world's children 2009: maternal and new born health (PDF). UNICEF.

- Dhar, Aarti (18 January 2009). "40 p.c. child marriages in India: UNICEF". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- "Child Sexual abuse and law". ChildLineIndia. Dr.Asha Bajpai.

- "Parliament passes bill to protect children from sexual abuse". NDTV. 22 May 2012.

- The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act, 2012 Kerala Medico-legal Society website

- Law for Protecting Children from Sexual Offences

- Taneja, Richa (13 November 2010). "Activists bemoan lack of laws to deal with child sexual abuse". DNA India. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Need stricter laws to deal with child abuse cases: Court". The Indian Express. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". www.censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- Punj, Shweta (3 November 2017). "Human trafficking for sex: Thousands of girls live in slavery while society remains silent". India Today. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- "Article 21 in The Constitution Of India 1949". indiankanoon.org. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- Shah, Shreya (16 October 2012). "India's Missing Children, By the Numbers".

- Harlan, Emily K. "It Happens in the Dark: Examining Current Obstacles to Identifying and Rehabilitating Child Sex-Trafficking Victims in India and the United States." University of Colorado Law Review, vol. 83, 01 July 2012, p. 1113.

- "Vulnerable Children - Child Trafficking India". www.childlineindia.org.in.

- , Chopra, Geeta. Child Rights in India. [Electronic Resource]: Challenges and Social Action. Springer eBooks., New Delhi: Springer India : Imprint: Springer, 2015., 2015.