2013 European floods

Extreme flooding in Central Europe began after several days of heavy rain in late May and early June 2013. Flooding and damages primarily affected south and east German states (Thuringia, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Lower Saxony, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg), western regions of the Czech Republic (Bohemia), and Austria. In addition, Switzerland, Slovakia, Belarus, Poland, Hungary and Serbia (Vojvodina) were affected to a lesser extent.[5][6] The flood crest progressed down the Elbe and Danube drainage basins and tributaries, leading to high water and flooding along their banks.

Flood in Havelberg, Germany, on 10 June 2013 | |

| Date | May–June 2013 |

|---|---|

| Location | Austria, Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland |

| Deaths | 25[1][2][3] |

| Property damage | Overall losses €12bn (US$ 16bn) insured loss in the region of €3bn (US$ 3.9bn).[4] |

Meteorological history

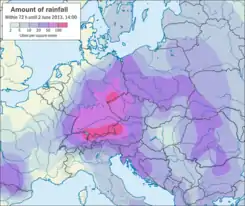

The spring weather preceding the flooding had been wet in the region, and May 2013 had been one of the three wettest in the last 156 years in Austria, together with the years 1962 and 1965. Austria saw twice as much rainfall as average during the month,[7] resulting in the ground in the region becoming saturated. Soils in Germany were showing record levels of moisture prior to the rains.[8] The already saturated soils led to greater runoff when the rains began.

In last ten days of May a low pressure system named "Christoffer" swung up from the Mediterranean across the Black Sea then across Ukraine and Poland to Northern Germany, eventually bringing a very moist, and warm airmass to Central Europe from north-east.[9] Late May saw a blocking high "Sabine" located over the Sole sea area to the west of the UK and France. This split the jet stream over Europe which maintained the weather pattern in Central Europe.

Spring and summer flooding in Central Europe is commonly associated with the so-called "Zugstrasse Vb" track of low pressure areas, which bring low pressure and moist air from the Mediterranean Sea over Central Europe, and have led to severe flooding in the affected region before. Though later analysis found this flooding did not fit into this type.[10]

Low pressure areas "Frederik" and "Günther" formed over the northern Adriatic and tracked north towards central Europe. The high pressure "Sabine" and low pressure areas brought an airflow from the north across Germany, which brought the water-laden air from the north east. The air mass was pushed to the south west by the northerly flow, where it was lifted as it moved south from the North European Plain over the Thuringian Forest, Ore Mountains, and Bohemian Forest. The air was then lifted along the north side of the Alps in Austria as the air masses were pushed into the Alps by the northerly flow, which led to intense orographic precipitation. Heavy rain was reported in the Austrian states of Vorarlberg and Tyrol and the area of Salzburg, and to the mountains of Upper Austria and Lower Austria and Upper Styria in a short time.

On 30 May to 1 June, 150 to 200 mm of rain (5.9 to 7.9 in of rain) fell, in places reaching around 250 mm (9.8 in), which in just a few days was the equivalent normally seen over two and a half months on average.[11] The rainfall experienced in Austria has an expected return period of between 30 and 70 years. The bulk of the rain fell in only two days in Salzburg, Tyrol, and Vorarlberg, which is thought to have a return period of more than 100 years.[12]

Following the intense rain, sporadic showers and rainfall continued to raise the risk of further flooding but no rainfall of the intensity as that seen on 31 May-2 June occurred.[13] Some Flash flooding occurred in the Polish capital Warsaw on 9 June, as a result of thunderstorms.[14]

The flood waters were expected to exceed the levels seen during the disastrous "once in a century" Central European floods of 2002 in some areas. In Bavaria and eastern Germany water levels significantly exceeded those of 2002 in many places on the Danube and Elbe. In Passau, at the confluence of the rivers Danube, Inn and Ilz, the highest water level since 1501 was recorded. In Dresden, by contrast, the old city centre was largely spared, unlike in 2002. Thanks to better flood control, fewer dykes on the upper reaches of the Elbe broke than in 2002, but this meant that the flood wave further downstream was all the higher. In Magdeburg, the floods reached a record level.[4]

Climatological context

Stefan Rahmstorf, a professor of ocean physics at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, stated that a low-pressure system that dumped the rain was locked into place by a disturbance with the global wind pattern. Linking the weather to the concurrent drought conditions in Russia, he said pressure systems stay locked in place, causing a persistent pattern of weather in an area. He also stated that this planetary wave resonance is not a local effect but spread around the whole (northern) hemisphere. When a “resonance” episode occurs, half a dozen peaks and troughs of high or low pressure form around the hemisphere. This explains why some parts of the world become unseasonably hot or cold and others unusually dry or rainy.[15]

According to The Inquirer/Agence France-Presse, the resonance hypothesis has been widely discussed among climate scientists, but has met resistance among experts who are wary of associating single extreme-weather events with climate change; the European Environment Agency cautioned that more data were needed to confirm it.[16]

Climate scientists have estimated that the flooding regime, which has prior inflicted severe flooding once every 50 years, to become more frequent, and cause severe flooding once every 30 years.[17] The cost of flooding in the European continent, which currently causes an estimated 4.9 billion Euros of damage per year, is expected to increase to 23.5 billion Euros per year.[18]

Hydrological development

The Austrian meteorological centre (ZAMG) said Austria had experienced at the beginning of June as much rain in two days as it normally would in two months.[19] Train lines in many parts of northwest Austria were suspended on 1 June due to landslides according to Austrian Federal Railways. The town of Ettenau was evacuated, while one person in Sankt Johann im Pongau near Salzburg was caught in a mudslide and died.[19] Rail services between Munich and the Austrian city of Salzburg also were suspended.[19] One section of a Swiss motorway was shut down due to flooding, along with many smaller roads throughout the country. Swiss officials said water levels were still rising and landslides remained a risk, although the general situation was under control.[19]

Elbe basin

The upper areas of the Elbe basin saw heavy rainfall, with the Vltava (Czech Republic) and the Saale (Germany) tributaries flooding.

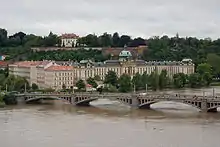

Vltava river

In the Czech capital Prague, floodwaters covered the esplanades along the Vltava, which on 3 June flowed at a rate of 3,200 m3/s (110,000 cu ft/s), compared to the almost 5,000 m3/s (180,000 cu ft/s) in the devastating floods of 2002.[20][21] Parts of all three city metro lines were closed. The transit authority provided alternative transport in the form of buses and special trams.[22] Heavy machinery was brought in to protect the historic Charles Bridge in the city, as a digger with an extended 17-metre (56 ft) long arm was used to clear debris from accumulating at the bridge.[22] One thousand troops from the Czech Army were called in to help build flood defences.[21] Fire fighters helped evacuate more than 7,000 people on 2 – 3 June from areas hit by the floods, in the region of central, northern and western Bohemia, including parts of the Czech capital.[22]

In Prague, the Hostivař and Záběhlice neighbourhoods in the southeast of the city were flooded. Hundreds of homes in Modřany and Zbraslav in the south of the city were also evacuated while some people in Lahovice and Velká Chuchle were rescued by helicopter.[22] The tigers at Prague Zoo were tranquilised and moved out of their enclosure, which was at risk from flooding.[23] The Czech government declared a state of emergency in seven regions of the country including Prague, in response to the floods.[24] Petr Nečas, the Czech prime minister, announced on 4 June that the government will release 4 billion CZK (€ 155m, £ 133m, $ 203m) from the state reserves to repair the damage.[25] More than 19,000 people were evacuated in the Czech Republic (as of 5 June 2013).[26] In Prague the Staropramen Brewery on the river bank was closed as a protective measure, along with several major chemical factories, including Spolana, which had released dangerous toxic chemicals into the Elbe during the devastating floods of 2002.[27]

Saale river

In the state of Saxony-Anhalt, the Saale river also caused concern, with officials fearing that it might rise even higher than in 2002.[28] In the area around Halle alone, authorities told some 30,000 people to evacuate their homes, the Saale river, a tributary of the Elbe, had risen 26 feet (7.9 m) above its normal level. In Halle one of the city's main sources of tourist income is the Handel music festival, which was called off.[29]

Elbe river

In the state of Saxony, the old town of Grimma, on the Mulde tributary was under metres of water. Authorities were concerned about the Elbe river; in Dresden one of the bridges across the river was closed to traffic.[28] In the city of Magdeburg, authorities declared a state of emergency and said they expected the Elbe river to rise higher than in 2002.[30] In Magdeburg with water levels of five metres (16 ft) above normal about 23,000 residents had to leave their homes on 9 June.[31]

In the area surrounding the city of Leipzig, some 6,000 people had to be evacuated on 4 June.[28] In Zwickau, Saxony the Volkswagen factory had to stop its car production, a spokesman said 3 June early shift had been asked to stay at home, with damage done to transport infrastructure raising fears that suppliers would not be able to deliver their products in time. The factory was able to resume production by 4 June.[32] German armed forces were able to protect chemical production facilities in the Middle German Chemical Triangle from the floods.[32]

Danube basin

The historic centre of Passau, where the Danube, Inn and Ilz converge, was underwater on 1 June 2013,[19] with the water levels reaching 12.85 m (42.2 ft), overflowing the highest recorded historic flood level.[33][34]

After a dike failed near the town of Deggendorf, water levels rose to a record-breaking eight metres (26 ft). The town flooded and in places buildings were two metres (6 ft 7 in) underwater. In the Fischerdorf area of the town, water lapped at second-storey windows. Some residents refused to evacuate, fearful of looting and not wanting to leave their lives behind. The town's fire station was underwater, with car dealerships holding millions of euros worth of vehicles destroyed.[35]

Flooding affected German businesses with Krones, a bottling and packaging manufacturing company, shutting down production in two plants in upper Bavaria, as workers were unable to get to work on the inundated roads.[32]

The entire Austrian stretch of the Danube saw all shipping halted.[23]

Budapest, Bratislava, and other river cities along the Danube enacted emergency preparations.[21] In Bratislava, the Danube peaked with a volumetric flow rate of 10,530 m3/s (372,000 cu ft/s), which is the highest flow rate ever recorded in Bratislava.[36] In Hungary, the Prime Minister Viktor Orbán declared a state of emergency in some areas along the Danube, which was expected to peak 5 June in western areas and hit Budapest the following weekend. He announced the government had mobilised 8,000 soldiers, 8,000 emergency personnel, 1,400 water management experts, and 3,600 police officers to deal with the situation.[30]

Rhine river

Flooding along the Rhine watershed was less severe in terms of flood damage. Shipping was halted on extensive stretches of the Rhine, Main, and Neckar rivers.[19]

Reaction

The European Commission stated that help would be available to the victims of the current flooding through the European Union Solidarity Fund, which it set up after the last major floods to hit the region in 2002.[37] The floods led to the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters being activated, which provides a unified system of data acquisition and delivery to those affected by disasters.[38] On June 3, the German Federal civil protection authorities triggered the Copernicus Emergency Mapping Service via the European Commission's Emergency Response Centre.[39]

Insurance industry specialists said they expected insurance losses to fall short of the last big floods to hit the region in 2002, some areas experienced higher waters, but investment over the previous ten years has meant that flood defences in a number of locations worked better than in 2002.[40]

Fatalities

Twenty-five deaths were recorded as a result of the floods; eleven in the Czech Republic,[1] six in Austria,[2] and eight in Germany.[3]

References

- "Smutná bilance povodní: 11 mrtvých" (in Czech). Lidovky.cz. 2013-06-08. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- Neun Tote in den Nachbarländern (in German)

- "Insgesamt 8 Tote bei Hochwasser – Weiter Gefahr von Deichbrüchen", Badische Zeitung, 12 June 2013

- "Floods dominate natural catastrophe statistics in first half of 2013". Munich Re. 9 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-07-14. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- "Central Europe hit by floods after days of rain". The Island Packet (originally Associated Press). 2 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- "Povodně trápí celou střední Evropu, Dunaj stoupl v Pasově k deseti metrům". Mladá fronta DNES (in Czech). iDNES. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- "Update Starkregen und Rückblick Mai" (in German). ZAMG. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "SMOS Maps Record Soil Water Before Flood". European Space Agency. 7 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-06-09. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Storm2k".

- Grams, C. M.; Binder, H.; Pfahl, S.; Piaget, N.; Wernli, H. (4 July 2014). "Atmospheric processes triggering the central European floods in June 2013". Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 14 (7): 1691–1702. Bibcode:2014NHESS..14.1691G. doi:10.5194/nhess-14-1691-2014.

- "Extremer Dauerregen geht zu Ende". ZAMG (in German). 2 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "Wetter beruhigt sich allmählich". ZAMG. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "Europe Flood Threat Continues". Accuweather. 8 June 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Dutton, Liam (10 June 2013). "Flash flooding hits Warsaw – video". Channel 4 News. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Petoukhov, V.; Rahmstorf, S.; Petri, S.; Schellnhuber, H. J. (2013). "Quasiresonant amplification of planetary waves and recent Northern Hemisphere weather extremes" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (14): 5336–5341. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.5336P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222000110. PMC 3619331. PMID 23457264. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Climate and land use: Europe's floods raise questions". Inquirer News (Agence France-Presse). 5 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Scientific American".

- "Nature".

- "Deadly Floods hit Germany and Central Europe". Deutsche Welle. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Prague spared worst of flooding as north Bohemia remains on high alert". Radio Praha. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- "Thousands flee as central Europe flood waters rise". BBC News. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "News". Radio Praha. 3 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-04. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- Hovet, Jason; Jana Mlcochova (3 June 2013). "Czech capital on alert as floods swamp central Europe". Reuters. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Heavy flooding reaches Prague [VIDEO]". The Prague Post. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- "Nečas: Na povodňové škody jsou v rozpočtu vyhrazeny 4 miliardy" (in Czech). Czech Television. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "ON-LINE: Velká voda vyhnala z domovů 19 tisíc lidí" (in Czech). novinky.cz. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- Rising, David (4 June 2013). "German troops sent in to help its flooded cities". The San Bernardino Sun. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Hengst, Björn (4 June 2013). "Historic High Water: Passau Suffers Worst Flood in 500 Years". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Patterson, Tony (6 June 2013). "In Halle, the birthplace of Handel, 'Water Music' has a new resonance: Horrendous floods have left people fighting for their homes – and their lives". The Independent. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Merkel pledges €100 million in flood aid". The Local (de). 4 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Thousands evacuated as Elbe bursts dam in German floods 10 June 2013

- Wenkel, Rolf (4 June 2013). "Floods hit Germany at economic low point". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ert. "Dunaj v Pasově překonal historický rekord, povodně porouchaly vodoměr – iDNES.cz". Zpravy.idnes.cz. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- "Central Europe Hit by Rains, Floods and Landslides: AIR Analysis". Insurancejournal.com. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- "Deggendorf devastated: Danube floods town". The Local (de). 7 June 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Povodne vo štvrtok: Dunaj v Bratislave pozvoľne klesá, vlna smeruje nižšie". SME.sk. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- "Merkel pledges immediate support as floods travel north". Deutsche Welle. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- "Flood Mapping Through the International Charter". European Space Agency. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Current floods in central Europe: awareness and monitoring". European Commission, Joint Research Centre. 6 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Europe's insurers seen escaping brunt of flood damage". Reuters. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

External links

Media related to Central Europe floods, May/June 2013 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Central Europe floods, May/June 2013 at Wikimedia Commons- Animation of rainfall in Europe 29 May- 1 June Earth Observation Group University of Copenhagen.

- NASA Earth Observatory, Image of the Day: Flooding in Eastern Germany

- International Charter Space and Major Disasters, Images and Image products delivered under the charter for 2013 Floods in Germany.

- Copernicus Emergency Management Service mapping: Czech Republic Germany Hungary

- Kristalina Georgieva, EU Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection: Floods in Central Europe

- EU Emergency Response Centre state of play maps summarising the flood situation in Central Europe: 5 June 2013 6 June 2013 10 June 2013 11 June 2013 12 June 2013 13 June 2013 14 June 2013 17 June 2013

- DWD's chronological overview from 29 May to 2 June 2013

- DWD's Meteorological report (in German)