270 Park Avenue

270 Park Avenue (also known as the JPMorgan Chase Tower and formerly the Union Carbide Building) was a high-rise office building located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It was designed by Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. 270 Park Avenue was built between 1957 and 1960 and was 708 ft (216 m) tall.

| 270 Park Avenue | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Main facade of 270 Park Avenue in 2008. | |

| |

| Former names | Union Carbide Building |

| General information | |

| Status | Under demolition |

| Location | 270 Park Avenue, Manhattan, New York, NY 10017, United States |

| Construction started | 1957[1] |

| Completed | 1960 |

| Closed | 2018 |

| Demolished | 2019–2021 |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 708 ft (216 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 52 |

| Floor area | 2,400,352 sq ft (223,000.0 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Gordon Bunshaft Skidmore, Owings and Merrill |

As of 2019, the building is being demolished to make room for a taller building on the same site. It is the tallest voluntarily demolished building in the world, overtaking the previous record holder Singer Building that was demolished in 1968.[2] The building was the world headquarters for JPMorgan Chase, and during the deconstruction, 383 Madison Avenue is serving as temporary headquarters.[3]

History

Hotel and residences

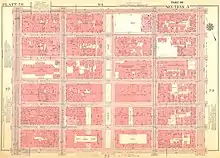

After the construction of Grand Central Terminal in 1913, the now fashionable "Terminal City" area north of the terminal was ripe for investment. Developer Dr. Charles V. Paterno built what was called the largest apartment building in the world with two distinct sections.[4] The mansion-like apartments that took the address 270 Park Avenue, and the apartment hotel that used the name Hotel Marguery on Madison Avenue. The residents would share a 70-by-275-foot (21 by 84 m) garden with a private drive. As the restrained brick and stone structure rose, Manhattan millionaires rushed to take apartments.

The 6-building complex which formed the 12-story, stone-clad Renaissance Revival Hotel Marguery[1][5] was built in 1917 by Dr. Paterno at a cost of more than $5 million.[6] New York Central Railroad owned the land underneath the project since the construction of Grand Central Terminal.[7] The buildings were centered around a 250-foot-long Italian Garden which occupied the center of the block.[8] When the building was first constructed, Vanderbilt Avenue passed through the center of the buildings where the garden was eventually built. After the street was closed, the hotel built a 60 feet (18 m) tall carriage arch which allowed private access to the courtyard.[8] The buildings contained 29 stores, 180 long-term apartments, and 110 luxury suites which ranged from 6 to 16 rooms apiece.[7] By the 1940s, the high-end apartments rented for over $20,000 per month on average.[6]

On January 3, 1930, an explosion started a fire in the basement of the building which cut power and killed two people due to smoke inhalation.[9] In 1933, the hotel's owners sued to reduce their property taxes significantly on the grounds that the property's assessed value was almost $5 million too high.[10] After eight years in court, Justice Charles B. McLaughlin reduced the assessment in 1941 by an aggregate $19.588 million for the previous eight years, resulting in a refund of over $600,000 to the hotel's owners.[11] In 1923, Nikola Tesla rented rooms at the Hotel Marguery.[12] Harry Frazee, the owner of the Boston Red Sox who sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees, also lived here.[13] In June 1945, a wealthy textile executive named Albert E. Langford was shot to death in the hallway outside of his apartment on the seventh floor of the Hotel Marguery.[14] In September 1947, the NYPD busted an underground gambling ring in the hotel, arresting 11 men.[15]

CBS and Time Inc.

Plans for a replacement to the Hotel Marguery had first surfaced in 1944, when William Zeckendorf's Webb and Knapp planned a new 34-story structure.[7][16] The building would have had a limestone facade with decorative vertical stainless steel columns.[17] In 1945, CBS agreed to occupy the building but quickly backed out.[6] Department store Wanamaker's also reportedly considered the site for an uptown location in addition to the main branch at Broadway and Ninth.[6] Plans for the new structure faced a setback in 1946 when the Office of Price Administration denied Webb & Knapp's petition to evict the 116 residents of the building.[18]

In the late 1940s, Time Inc. had an option to purchase the property and build a new headquarters for the company.[19] The company planned a 39-story, 1 million square feet (93,000 m2) building designed by Harrison & Abramovitz which was approved in June 1947, despite the protests of the hotel tenants.[7][20] Time would have occupied 350,000 square feet (33,000 m2) of the space as its new world headquarters. At $23 million, the project was expected to be the largest private construction project in Manhattan since the end of World War II.[7] Following the new tower's approval, the Marguery's tenants announced they would fight the decisions in the courts and through the city's Office of Rent Control.[21] The tenants of the hotel hired New York prosecutor Peter McCoy as their attorney to oppose the destruction of the buildings. McCoy had previously prosecuted stockbrokers for the government before entering private practice.[22] The tenants also appealed to the New York City Council to oppose the demolition.[23] In 1948, the hotel closed as it had lost its luster and was reportedly "heavily populated by ladies of the night and by gambling outfits.”[19] Due to the failure to evict the Marguery's tenants, Time gave up on the plans for a new tower in March 1950.[24] Ultimately, Time instead moved to 1271 Avenue of the Americas at Rockefeller Center in 1958.

Union Carbide Building

By 1951, the Hotel Marguery's former Italian Gardens had been converted to a parking lot.[6] The same year, Webb & Knapp unveiled plans to spend $50 million building a 44-story, 580 feet (180 m) tall office building on the site. The building would be topped by a 1,000 feet (300 m) tall steel latticework observation tower, making the proposed building taller than the Empire State Building and the tallest building in New York City.[25]

After threatening to move to suburban Elmsford, New York in Westchester County, chemical company Union Carbide agreed to lease the site in August 1955 to serve as its world headquarters.[19] The company signed a lease with the New York Central Railroad to pay $250,000 per year plus the property's real estate taxes (estimated to be $1.5 million per year) for a term of at least 22 years.[26] In addition, Union Carbide paid the railroad $10 million for the option to acquire the land outright in the future. At the time, the Marguery had been almost entirely converted from apartments into office suites. Some of the 250 tenants included Renault, Rheem Manufacturing Company, Georgia-Pacific, Nedick's, Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, Airlines for America, The Manila Times, and the United Nations delegations for Mexico, Ethiopia, Liberia, and Venezuela.[26][27]

In August 1955, the company unveiled plans for a 41-story, 800,000 square feet (74,000 m2) office building on the site which would be entirely occupied by the company and completed by 1958.[6] In July 1956, architects Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill increased the size of building by 11 stories to 52 floors and Union Carbide pegged the new tower's cost at $46 million.[28][29] Demolition of the former hotel began in early 1957 and was completed by late August.[8] The new building was completed in 1961 and maintained the distinction of being the tallest woman-designed building in the world for almost 50 years.

The first 700 Union Carbide employees moved into the building in April 1960.[30] By the building's completion, Union Carbide occupied 41 floors home to over 4,000 employees. Other early tenants in the building included management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, who occupied 64,000 square feet (5,900 m2) of space.[31] In 1976, Union Carbide purchased the land beneath the building from the bankrupt Penn Central Transportation Company for $11 million.[32] The building continued to serve as the headquarters for Union Carbide until the company moved to Danbury, Connecticut in 1981.[33]

Manufacturers Hanover Trust

By early 1975, discussions had already begun between the Union Carbide Company and Manufacturers Hanover Trust about selling the building.[34] In June 1978, Manufacturers Hanover Trust purchased the building for $110 million with plans to move its world headquarters to the building in 1980.[32] In the early 1980s, the company spent $75 million to renovate the building into its world headquarters.[35] The changes including removing the mezzanine level (which had served as an industrial products display for Union Carbide) to create a double-height lobby, constructing two fountains in the plaza, and renovations of interior flooring, ceilings, and fixtures. Following the renovations, Manufacturers Hanover Trust occupied the entire building with over 3,000 employees, other than 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) on the sixth and seventh floors which was leased to a Japanese importer.[35]

JPMorgan Chase

Under Chairman Donald Platten, Chemical's headquarters moved to 277 Park Avenue in 1979.[36][37][38] The bank moved across Park Avenue in 1991 to occupy the former headquarters of Manufacturers Hanover Corporation at 270 Park Avenue, which remained the headquarters of Chemical's successor, JPMorgan Chase

In 2012, JPMorgan Chase announced that 270 Park had achieved Platinum LEED status following what was then the largest such renovation in history.[39]

The building was vacated in 2018 in preparation for demolition and construction of a new JPMorgan Chase headquarters on the same site.

Demolition and replacement

In February 2018, JPMorgan announced it would demolish the current building on the site to make way for a newer building that will be 715 feet (218 m) taller than the existing structure. The tower would thus become the tallest voluntarily demolished building in the world, as well as the third-tallest ever to be destroyed, after the World Trade Center Twin Towers. The demolition began in 2019, and the new building is expected to be completed. The replacement 1,423 feet (434 m) and 70-story headquarters will have space for 15,000 employees, whereas the current building accommodates 6,000 employees in a space designed for a capacity of 3,500. The new headquarters is part of the East Midtown rezoning plan. Tishman Construction Corporation will be the construction manager for the project.[40] To build the larger structure, JPMorgan purchased hundreds of thousands of square feet of air rights from nearby St. Bartholomew's Episcopal Church as well as from Michael Dell's MSD Capital, the owner of the air rights above Grand Central Terminal.[41][42]

In October 2018, JPMorgan announced that British architectural firm Foster + Partners would design the new building. The plans for the new building had grown to 1,425 feet (434 m), though the zoning envelope allowed for a structure as high as 1,566 feet (477 m).[43] However, this also raised concerns that the taller building would require deeper foundations that could interfere with the Metropolitan Transportation Authority's East Side Access tunnels and the Grand Central Terminal's rail yards, which are directly underneath 270 Park Avenue.[44]

In May 2019, New York City Council unanimously approved JPMorgan's headquarters.[45] In order to secure approvals, JPMorgan was required to contribute $40 million to a district-wide improvement fund and incorporate a new 10,000 square feet (930 m2) privately owned public space plaza in front of the tower. After pressure from Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer and City Council member Keith Powers, JPMorgan also agreed to fund numerous upgrades to the public realm surrounding the building including improvements to Grand Central's train shed as well as a new entrance to the station at 48th Street.[46] In July 2019, the MTA and JPMorgan Chase signed an agreement, in which JPMorgan agreed to ensure that the deconstruction of 270 Park Avenue would not disrupt the timeline of East Side Access.[47]:22

In July 2019, scaffolding was wrapped around the tower and podium structure on the Madison Avenue side of the building, marking the beginning of building demolition. Demolition is scheduled to be done at the end of 2020, and the new building is expected to be completed sometime.[48]

2014 (Before demolition)

2014 (Before demolition) July 2019

July 2019 October 2019

October 2019

In popular culture

- When the Hotel Marguery occupied 270 Park Avenue, the 1947 film noir Kiss of Death used it as one of several New York City locations.[49]

- The current office building was used in exterior shots as the headquarters for the "World Wide Wicket Company" in the 1967 movie How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

See also

References

- "JPMorgan Chase Tower". Emporis. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- "World's tallest demolished buildings" (PDF). CTBUH Journal (II): 48–49. April 27, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "JPMorgan weighs shifting thousands of jobs out of New York area". American Banker. October 28, 2019. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- "The Lost Hotel Marguery -- No. 270 Park Avenue". Daytonian in Manhattan. November 9, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- "Completing Big Apartment" (PDF). The New York Times. June 17, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Bradley, John (August 17, 1955). "New Skyscraper Set For Park Ave" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Cooper, Lee (June 4, 1947). "300 to be Ousted for New Building" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Final Razing Begins at Marguery Hotel" (PDF). The New York Times. July 26, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Two Die as Blast Rocks the Marguery and Routs Guests" (PDF). The New York Times. January 4, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Assessment Suits Filed" (PDF). The New York Times. April 19, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Tax Value Cut Sharply For 270 Park Avenue" (PDF). The New York Times. December 19, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Tesla Timeline – 1923: Tesla Moves To Hotel Marguery". Tesla Universe. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Leavy, Jane (December 30, 2019). "Opinion | Why on Earth Did Boston Sell Babe Ruth to the Yankees?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- "Wealthy Textile Executive Killed in Park Avenue Mystery Shooting" (PDF). The New York Times. June 5, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Crooked 'Sucker' Set-Up Seized In Park Avenue Gambling Raid" (PDF). The New York Times. September 12, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Gray, Christopher (May 14, 1989). "Is It Time to Redevelop Park Avenue Again?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Cooper, Lee (July 22, 1945). "Office Skyscraper to Rise on Marguery Hotel Block" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "OPA Bans Marguery Evictions" (PDF). The New York Times. May 30, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Pollak, Michael (July 15, 2007). "Shutting It Off, Already". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "East Side Offices to Cost $21,164,000" (PDF). The New York Times. June 25, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Tenants To Fight Against Evictions" (PDF). The New York Times. June 5, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Peter J. M'Coy, 70, Former U.S. Aide". The New York Times. July 19, 1958. p. 15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "500 Hotel Tenants Act to Bar Eviction" (PDF). The New York Times. June 20, 1947. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Abandon Project on Marguery Site" (PDF). The New York Times. March 4, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Offices Planned in Park Ave. Block" (PDF). The New York Times. May 25, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Bradley, John A. (August 21, 1955). "Marguery Deal Nets Big Profit" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Rheem Co. Leases Marguery Offices" (PDF). The New York Times. May 31, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Taller Building Due For Marguery Site" (PDF). The New York Times. July 28, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Glass to Enclose 52-story Building" (PDF). The New York Times. February 5, 1957. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Union Carbide Starts Moving to 270 Park" (PDF). The New York Times. April 19, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- "Tenant Enlarges Park Ave. Office" (PDF). The New York Times. July 4, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Milletti, Mario (June 29, 1978). "Manufacturers Hanover to Buy Union Carbide's Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Tomasson, Robert (September 27, 1981). "An Industrial Giant Relocates Its Extended Family". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Horsley, Carter (April 24, 1975). "Union Carbide Seeking to Sell Building and Move Out of City" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Goodman, George (October 30, 1983). "Manufacturers Hanover Remodels Its Skyscraper". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- Barron, James (August 27, 1991). "Donald C. Platten, Ex-Chairman Of Chemical Bank, Is Dead at 72". The New York Times.

- "Chemical Bank Selling Building". The New York Times. April 10, 1981.

- Horsley, Carter B. "The Chase Building". The Midtown Book. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- "JPMorgan Chase Achieves LEED® Platinum Green Building Certification for Newly Renovated Global Headquarters in New York City" (Press release). JPMorgan Chase. January 18, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2020 – via BusinessWire.

- Bagli, Charles V. (February 21, 2018). "Out With the Old Building, in With the New for JPMorgan Chase". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Davis, Michelle (June 28, 2018). "JPMorgan Buys Air Rights From Midtown Church to Build Its New HQ". Bloomberg News. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- Levitt, David M. (February 26, 2018). "JPMorgan Buys Rights for HQ From Michael Dell Partnership". Bloomberg News. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- Fedak, Nikolai (November 12, 2018). "270 Park Avenue's Replacement Will Rise 1,400 Feet in Midtown East, Manhattan". New York YIMBY. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Geiger, Daniel (December 13, 2018). "JPMorgan tower could interfere with MTA megaproject". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Small, Eddie (May 8, 2019). "City Council gives green light for JMorgan's new headquarters in Midtown East". The Real Deal. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- Katz, Lily (March 26, 2019). "JPMorgan Agrees to Fund Transit Upgrades Near Its New Manhattan Headquarters". Bloomberg News. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- "Capital Program Oversight Committee Meeting" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 22, 2019. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Young, Michael (December 27, 2019) "270 Park Avenue's Demolition Continues in Preparation for JP Morgan's New Supertall in Midtown East" Yimby

- Pryor, Thomas M. (May 11, 1947). "Manhattan Doubles as Movie Set; Henry Hathaway Looks For Realism and Finds It Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

External links

Media related to 270 Park Avenue at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 270 Park Avenue at Wikimedia Commons