ARA Rivadavia

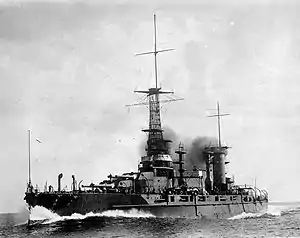

ARA Rivadavia (Spanish: [riβaˈðaβja]) was an Argentine battleship built during the South American dreadnought race. Named after the first Argentine president, Bernardino Rivadavia,[2] it was the lead ship of its class. Moreno was Rivadavia's only sister ship.

ARA Rivadavia | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Rivadavia |

| Namesake: | Bernardino Rivadavia |

| Builder: | Fore River Shipbuilding Company |

| Laid down: | 25 May 1910 |

| Launched: | 26 August 1911 |

| Commissioned: | 27 August 1914 |

| Decommissioned: | 1952 |

| Fate: | Sold to Italy for scrapping in 1957 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Rivadavia-class battleship |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | |

| Beam: | 98 ft 4.5 in (29.985 m)[1] |

| Draft: | 27 ft 8.5 in (8.446 m)[1] |

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 22.5 knots (25.9 mph; 41.7 km/h)[1] |

| Range: | |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

In 1907, the Brazilian government placed an order for two of the powerful new "dreadnought" warships as part of a larger naval construction program. Argentina quickly responded, as the Brazilian ships outclassed anything in the Argentine fleet. After an extended bidding process, contracts to design and build Rivadavia and Moreno were given to the American Fore River Shipbuilding Company. During their construction, there were rumors that the ships might be sold to a country engaged in the First World War, but both were commissioned into the Argentine Navy. Rivadavia underwent extensive refits in the United States in 1924 and 1925. The ship saw no active service during the Second World War, and its last cruise was made in 1946. Stricken from the naval register in 1957, Rivadavia was sold later that year and broken up for scrap starting in 1959.

Background

Rivadavia's genesis can be traced to the naval arms races between Chile and Argentina which were spawned by territorial disputes over their mutual borders in Patagonia and Puna de Atacama, along with control of the Beagle Channel. These arms races flared up in the 1890s and again in 1902; the latter was eventually stopped through British mediation. Provisions in the dispute-ending treaty imposed restrictions on both countries' navies. The United Kingdom's Royal Navy bought the two Constitución-class pre-dreadnought battleships that were being built for Chile, and Argentina sold its two Rivadavia-class armored cruisers under construction in Italy to Japan.[3][4]

After HMS Dreadnought was commissioned by the United Kingdom, Brazil decided in early 1907 to halt the construction of three obsolescent pre-dreadnoughts and begin work on two dreadnoughts (the Minas Geraes class).[5] These ships, which were designed to carry the heaviest battleship armament in the world at the time,[6] came as a shock to the navies of South America,[5] and Argentina and Chile quickly canceled the 1902 armament-limiting pact.[7] Argentina in particular was alarmed at the possible power of the ships. The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Manuel Augusto Montes de Oca, remarked that even one Minas Geraes-class ship could destroy the entire Argentine and Chilean fleets.[8] While this may have been hyperbole, either one was much more powerful than any single vessel in the Argentinian fleet.[9] Debates raged in Argentina over whether to spend more than two million pounds sterling to acquire dreadnoughts. With further border disputes, particularly with Brazil near the Río de la Plata (River Plate), Argentina made plans to contract for their own dreadnoughts. After an extended bidding process, Rivadavia and Moreno were ordered from the Fore River Shipbuilding Company in the United States.[1][10]

Construction and trials

Laid down on 25 May 1910, Rivadavia was launched and christened on 26 August 1911 by Isabel, the wife of the Argentine Minister to the United States Rómulo Sebastián Naón. Thousands of people were present to witness the event,[1][11] including representatives from the Argentine Navy and the country's legation in Washington. The United States sent the assistant chief of the Latin American Division in the State Department, Henry L. James, to be its official representative. Two United States Navy bureau chiefs also attended.[11]

In mid-September 1913, Rivadavia conducted trials off Rockland, Maine, after a two-week delay due to turbine malfunctions. During speed trials on the 16th,[12] the dreadnought was able to obtain a maximum speed of 22.567 knots (25.970 mph; 41.794 km/h).[13] On a 30-hour endurance trial starting the next day, Rivadavia damaged one of its turbines and had to put in at President Roads, one of Boston Harbor's deep-water anchorages.[12] The turbines were still a problem as late as August 1914. One was dropped by a crane in July and had to be removed for repairs in August.[14]

Attempted sale

Over the course of their construction, Rivadavia and Moreno had been the subject of rumors that Argentina would accept the ships and then sell them to Japan, a fast-growing military rival to the United States, or to a European country.[15] The rumors were partially true; some in the government were looking to get rid of the battleships and devote the proceeds to opening more schools,[16] and The New York Times reported in late 1913 that the country had received several offers from interested parties.[13] This angered the American government, which did not want its warship technology offered to the highest bidder. Neither did they want to exercise a contract-specified option that gave the United States first choice if the Argentines decided to sell, as naval technology had already progressed past the Rivadavia class, particularly in the adoption of the "all-or-nothing" armor scheme. Instead, the United States and its State Department and Navy Department put diplomatic pressure on the Argentine government.[17]

After socialist gains in the legislature, the Argentine government introduced several bills in May 1914 which would have put the battleships up for sale, but they were all defeated by late June. Following the commencement of the First World War, the German and British ambassadors to the United States both complained to the US State Department; the former believed that the British were going to be given the ships as soon as the ships reached Argentina, and the latter considered it the responsibility of the United States to ensure that the ships never left Argentina's possession. International armament companies attempted to get Argentina to sell to one of the smaller Balkan countries and expected that the ships would then find their way into the war.[18][upper-alpha 1]

Service

Rivadavia was commissioned into the Armada de la República Argentina on 27 August 1914 at the Charlestown Navy Yard,[19][20] although it was not fully completed until December.[1] On 23 December 1914, Rivadavia left the United States for Argentina. It arrived in its capital, Buenos Aires, on 19 February 1915. Over 47,000 people came out to see the new ship over the next three days, including the President Victorino de la Plaza. In April 1915, Rivadavia was put into the training division of the Navy, remaining there until 1917, when the navy transferred the ship into the First Division. In 1917, Rivadavia sailed to Comodoro Rivadavia when communist oil workers went on strike.[19]

Later in 1917, the Argentines had to sharply curtail Rivadavia's activities because of a fuel shortage, but they voyaged to the United States with the Argentine ambassador in 1918.[19] Rivadavia then took on a load of gold bullion and brought it back to Argentina, docking in Puerto Belgrano on 23 September 1918.[19][21] In December 1920, Rivadavia participated in ceremonies that marked the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the Strait of Magellan. On the 2nd, the ship called on Valparaíso in Chile; 25 days later, it took part in an international naval review. Two years later, Rivadavia was placed into reserve.[19]

In 1923, the Navy decided to send Rivadavia to the United States to be modernized. The ship departed on 6 August 1924 and reached Boston on the 30th, where it spent the next two years. Rivadavia was converted to use fuel oil instead of coal and had "a general machinery overhaul".[22] A new fire-control system was fitted with rangefinders on the fore and aft superfiring turrets, and the aft mast was replaced by a tripod. A funnel cap was installed so that smoke from the funnels did not interfere with accurate rangefinding of enemy ships. The 6-inch secondary armament was retained, but the smaller 4-inch guns were taken off in favor of four 3-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft guns and four 3-pounders.[23][24]

After sailing back to Argentina in March and April 1926,[25] Rivadavia spent the remainder of the year undergoing sea trials. The dreadnought joined the training division once again in 1927, but after Rivadavia made four training cruises, the division was disbanded, and the ship remained moored in Puerto Belgrano until 1929. This began a series of cyclic activity followed by being demoted to the reserve fleet. Although active in both 1929 and 1930, Rivadavia was placed in reserve on 19 December 1930. Shortly thereafter, it was restored to active service to serve as the flagship for 1931 fleet exercises. Rivadavia went back into reserve in 1932 before coming back out in January 1933. It remained in full commission for most of the rest of the decade as part of the Battleship Division, alongside Moreno.[19]

In January 1937, the ship called on Valparaíso and Callao in Peru. In company with Moreno, Rivadavia left Puerto Belgrano for Europe on 6 April. After crossing the ocean, they split up, with Rivadavia mooring at the French port of Brest while Moreno took part in the British Coronation Review in Spithead. The two ships then journeyed to several German ports: both put in at Wilhelmshaven before Rivadavia went to Hamburg and Moreno to Bremen. They returned to Argentina on 29 June.[19]

While Rivadavia made an official visit to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1939, Argentina remained neutral for the majority of the Second World War, and the aging dreadnought saw no active service.[19] Its next cruise came after the war ended (29 October to 22 December 1946), when it called on countries in the Caribbean and northern South America, including Trinidad, Venezuela, and Colombia. This was the last time the ship would be in service under its own power. Moored in Puerto Belgrano from 1948 on, the ship was rendered inoperable in 1951 and cannibalized for many years for useful arms and equipment. On 18 October 1956, the ship was listed for disposal, and it was stricken from the Navy on 1 February 1957. On 30 May, Rivadavia was sold to an Italian ship breaking company for US$2,280,000. Beginning on 3 April 1959, the ship was towed by two tugboats to Savona, Italy, where they arrived on 23 May. It was thereafter broken up in Genoa.[19]

Footnotes

- The specific example given in Livermore, footnote 106, is that a "group of French bankers, on behalf of the Russian government, were offering in gold twice the contract price of the ships, which were to be turned over to Greece."[18] Turning over the ships was likely meant as a way around the United States' neutrality rules.

Endnotes

- Scheina, "Argentina," 401.

- Whitley, Battleships, 19.

- Scheina, Naval History, 45–52.

- Garrett, "Beagle Channel Dispute," 86–88.

- Whitley, Battleships, 24.

- "Germany may buy English warships," The New York Times, 1 August 1908, C8.

- Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32.

- Martins Filho, "Colossos do mares," 76.

- Scheina, "Argentina," 400.

- Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 33.

- "Launch Rivadavia, Biggest Battleship," The New York Times, 27 August 1911, 7.

- "Accident to Rivadavia," The New York Times, 19 September 1913, 1.

- "Argentine Warship Makes 22.56 Knots," The New York Times, 17 September 1917, 2.

- "The Rivadavia Delayed," The New York Times, 24 August 1914, 7.

- "Germany Will Buy Two Battleships," Toronto World, 10 August 1914, 12.

- Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 45.

- Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 45–46.

- Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 46–47.

- Whitley, Battleships, 21.

- "Argentina's Ship Ready," The New York Times, 28 August 1914, 7.

- "Orders the Rivadavia to Bring Gold," The New York Times, 7 October 1918, 12.

- Scheina, "Argentina," 402.

- Whitley, Battleships, 21–22.

- Burzaco and Ortíz, Acorazados y Cruceros, 94.

- "Rivadavia Off For Home," The New York Times, 15 March 1926, 12.

References

- Burzaco, Ricardo and Patricio Ortíz. Acorazados y Cruceros de la Armada Argentina, 1881–1982. Buenos Aires: Eugenio B. Ediciones, 1997. ISBN 987-96764-0-8. OCLC 39297360.

- Martins, João Roberto, Filho. "Colossos do mares [Colossuses of the Seas]." Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional 3, no. 27 (2007): 74–77. ISSN 1808-4001. OCLC 61697383.

- Garrett, James L. "The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone." Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs 27, no. 3 (1985):, 81–109. JSTOR 165601. ISSN 0022-1937. OCLC 2239844.

- Livermore, Seward W. "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925." The Journal of Modern History 16, no. 1 (1944):, 31–44. JSTOR 1870986. ISSN 0022-2801. OCLC 62219150.

- Scheina, Robert L. "Argentina" in Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921, edited by Robert Gardiner and Randal Gray, 400–402. Annapolis, Maryland, United States: Naval Institute Press, 1985. ISBN 0-87021-907-3. OCLC 12119866.

- ———. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. ISBN 0-87021-295-8. OCLC 15696006.

- Whitley, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis, Maryland, United States: Naval Institute Press, 1998. ISBN 1-55750-184-X. OCLC 40834665.