Abai Qunanbaiuly

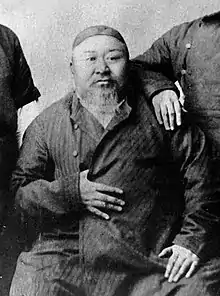

Abai Qunanbaiuly (![]() Абай Құнанбайұлы; 10 August 1845 – 6 July 1904) was a Kazakh poet, composer and Hanafi Maturidi theologian philosopher.[2] He was also a cultural reformer toward European and Russian cultures on the basis of enlightened Islam. His name is also transliterated as Abay Kunanbayev (Абай Кунанбаев); among Kazakhs he is known as Abai.

Абай Құнанбайұлы; 10 August 1845 – 6 July 1904) was a Kazakh poet, composer and Hanafi Maturidi theologian philosopher.[2] He was also a cultural reformer toward European and Russian cultures on the basis of enlightened Islam. His name is also transliterated as Abay Kunanbayev (Абай Кунанбаев); among Kazakhs he is known as Abai.

Abai Qunanbaiuly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Abai (Ibrahim) Qunanbaiuly 10 August 1845[1] Abay District, East Kazakhstan, Russian Empire[1] |

| Died | 6 July 1904 (aged 58)[1] Abay District, East Kazakhstan, Russian Empire[1] |

| Occupation | Aqyn |

| Nationality | Kazakh |

| Notable works | The Book of Words |

Life

Early life and education

Abai was born in Karauyl village in Chingiz volost of Semipalatinsk uyezd of the Russian Empire (this is now in Abay District of East Kazakhstan). He was the son of Qunanbai and Uljan, his father's second wife. They named him Ibrahim, as the family was Muslim, but he soon was given the nickname "Abai" (meaning "careful"), a name that stayed with him for the rest of his life.

The boy first studied at a local madrasah under Mullah Ahmet Ryza. His father was wealthy enough to send Abai to a Russian secondary school in Semipalatinsk. There he read the writings of Mikhail Lermontov and Alexander Pushkin, which were influential to his own development as a writer. Moreover, he was fond of reading eastern poetry, including Shahname and 1000 and 1 night.

Contributions

Abai's main contribution to Kazakh culture and folklore lies in his poetry, which expresses great nationalism and grew out of Kazakh folk culture. Before him, most Kazakh poetry was oral, echoing the nomadic habits of the people of the Kazakh steppes. During Abai's lifetime, however, a number of important socio-political and socio-economic changes occurred. Russian influence continued to grow in Kazakhstan, resulting in greater educational possibilities as well as exposure to a number of different philosophies, whether Russian, Western or Asian. Abai Qunanbaiuly steeped himself in the cultural and philosophical history of these newly opened geographies. In this sense, Abai's creative poetry affected the philosophical theological thinking of educated Kazakhs.

Legacy

The leaders of the Alash Orda movement saw him as their inspiration and spiritual predecessor.

Contemporary Kazakh images of Abay generally depict him in full traditional dress holding a dombra (the Kazakh national instrument). Today, Kazakhs revere Abay as one of the first folk heroes to enter into the national consciousness of his people. Kazakh National Pedagogical University is named after Abay, so is one of the main avenues in the city of Almaty. There are also public schools with his name. Abay is featured on postal stamps of Kazakhstan, Soviet Union, and India.

The Kazakh city of Abay is named after him.

Among Abay's students was his nephew, a historian, philosopher, and poet Shakarim Qudayberdiuli (1858–1931).

Statues of him have been erected in many cities of Kazakhstan, as well as Beijing, Moscow, New Delhi, Tehran, Berlin, Cairo, Istanbul, Kyiv, and Budapest.

Abay is featured on the Kazakhstani Tenge, a subway station in Almaty is named after him, along with a street, a square, a theater, and many schools.

In 1995, the 150th anniversary of Abay's birth, UNESCO celebrated it with the "year of Abai" event. A film on the life of Abay was made by Kazakhfilm in 1995, titled Abai. He is also the subject of two novels and an opera by Mukhtar Auezov, another Kazakhstani writer.

Another film describing his father's life was made in December 2015, titled "Qunanbai".

In 2016, Abay Qunanbaiuly was chosen as one of the nominees in the "proposed candidates" category of the national project «El Tulgasy» (Name of the Motherland) The idea of the project was to select the most significant and famous citizens of Kazakhstan whose names are now associated with the achievements of the country. More than 350,000 people voted in this project, and Abay was voted into 5th place in his category.[3]

In 2020, the government of Kazakhstan announced plans to celebrate the 175th anniversary of his birthday throughout the year.[4]

Works

Abay also translated into Kazakh the works of Russian and European authors, mostly for the first time. Translations made by him include poems by Mikhail Lermontov, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Lord Byron, Ivan Krylov's Fables and Alexander Pushkin's Eugene Onegin.

Abay's major work is The Book of Words («қара сөздері», Qara sózderi), a theologic philosophic treatise and collection of poems where he encourages his fellow Kazakhs to embrace education, literacy, and good moral character in order to escape poverty, enslavement and corruption. In Word Twenty Five, he discusses the importance of Russian culture, as a way for Kazakhs to be exposed to the world's cultural treasures.

Moscow protests in May 2012

On 9 May 2012, after two days of protests in Moscow following Vladimir Putin's inauguration as President of the Russian Federation for the third term, protesters set up camp near the monument to Abai Qunanbaiuli on the Chistoprudny Boulevard in central Moscow, close to the embassy of Kazakhstan. The statue quickly became a reference point for the protest's participants.[5] OccupyAbai was among the top ranking hash-tags in Twitter for several days thanks to Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny who set up a meeting with his followers next to Abai Qunanbaiuly's monument in Moscow that he called "a monument to some unknown Kazakh". This spurred a wave of indignation among ethnic Kazakhs who highly esteem Abai. This also brought Abai's poetry into the top 10 AppStore downloads.[6]

References

- АБА́Й КУНАНБА́ЕВ. Great Russian Encyclopedia

- "Significance of the creed of the Maturidi school in the works of Abay Kunanbayev and Shakarim Kudayberdiev" (in Russian). Journal of Oriental Studies.

- "ЕЛ ТҰЛҒАСЫ / ИМЯ РОДИНЫ / События / Разделы сайта / Деловой журнал Exclusive". 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- January 2020, Galiya Khassenkhanova in Culture on 22 (22 January 2020). "Abai's 175th anniversary to be celebrated throughout 2020". The Astana Times. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Vinokurova, Ekaterina (10 May 2012). "May protests in Moscow: The Whats and Whys". Gazeta.ru. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- "Russia had to provide security of Kazakhstan embassy during OccupyAbai campaign". Tengrinews.kz English. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Abai Qunanbaiuli |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Abai Kunanbaev. |

- Biography of Abay

- Site dedicated to Abay

- «Kara Sozder» (Book of Words) (in Kazakh)

- Poems by Abay (in Russian)

- IMDB page for the 1995 biopic