Abortion in Arkansas

Abortion in Arkansas is legal. Only 38% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Arkansas had an abortion ban in place by 1900. Reforms to abortion laws took place sometime in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The state constitution was amended in 1988 to condemn abortion. Abortion bills, including a partial-birth ban, took place in the late 1990s and unconstitutional pre-Roe v. Wade laws remained in place. Some of the abortion restricts have been taken to court, where they have been blocked from enforcement.

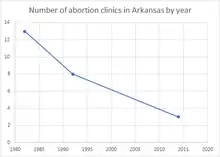

The total number of abortion clinics in the state has been declining for years, going from thirteen in 1982 to eight in 1992 to three in 2014. In 2014, 4,024 legal abortions took place in the state. This had declined in 2015 to 3,805. People from Arkansas participated in the #StoptheBans movement in May 2019.

Terminology

The abortion debate most commonly relates to the "induced abortion" of an embryo or fetus at some point in a pregnancy, which is also how the term is used in a legal sense.[note 1] Some also use the term "elective abortion", which is used in relation to a claim to an unrestricted right of a woman to an abortion, whether or not she chooses to have one. The term elective abortion or voluntary abortion describes the interruption of pregnancy before viability at the request of the woman, but not for medical reasons.[1]

Anti-abortion advocates tend to use terms such as "unborn baby", "unborn child", or "pre-born child",[2][3] and see the medical terms "embryo", "zygote", and "fetus" as dehumanizing.[4][5] Both "pro-choice" and "pro-life" are examples of terms labeled as political framing: they are terms which purposely try to define their philosophies in the best possible light, while by definition attempting to describe their opposition in the worst possible light. "Pro-choice" implies that the alternative viewpoint is "anti-choice", while "pro-life" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-death" or "anti-life".[6] The Associated Press encourages journalists to use the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion".[7]

Context

Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having a fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions. A 2014 New England Journal of Medicine study found such a link. At the same time, a 2011 study by Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health also found that states with more abortion restrictions have higher rates of maternal death, higher rates of uninsured pregnant women, higher rates of infant and child deaths, higher rates of teen drug and alcohol abuse, and lower rates of cancer screening.[8] The study singled out Oklahoma, Mississippi and Kansas as being the most restrictive states that year, followed by Arkansas and Indiana for second in terms of abortion restrictions, and Florida, Arizona and Alabama in third for most restrictive state abortion requirements.[8]

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.[9] According to Megan Donovan, a senior policy manager at the Guttmacher Institute, states have legislation seeking to protect a woman's right to access abortion services have the lowest rates of infant mortality in the United States.[9]

Poor women in the United States had problems paying for menstrual pads and tampons in 2018 and 2019. Almost two-thirds of American women could not pay for them. These were not available through the federal Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC).[10] Lack of menstrual supplies has an economic impact on poor women. A study in St. Louis found that 36% had to miss days of work because they lacked adequate menstrual hygiene supplies during their period. This was on top of the fact that many had other menstrual issues including bleeding, cramps and other menstrual induced health issues.[10] This state was one of a majority that taxed essential hygiene products like tampons and menstrual pads as of November 2018.[11][12][13][14]

History

One of the biggest groups of women who oppose legalized abortion in the United States are southern white evangelical Christians. These women voted overwhelming for Trump, with 80% of these voters supporting him at the ballot box in 2016. In November 2018, during US House exit polling, 75% of southern white evangelical Christian women indicated they supported Trump and only 20% said they voted for Democratic candidates.[15]

Legislative history

By the end of the 1800s, all states in the Union except Louisiana had therapeutic exceptions in their legislative bans on abortions.[16] In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, New Mexico, North Carolina and Oregon made reforms to their abortion laws, with most of these states providing more detailed medical guidance on when therapeutic abortions could be performed.[16] An amendment in the state constitution in 1988 said, "The policy of Arkansas is to protect the life of every unborn child from conception until birth, to the extent permitted by the Federal Constitution."[17]

Two abortion bills were before the state legislature in 1997. AB SB 612 (1997) was introduced by Republican Senator Boozman on March 5, 1997. While in committee, it was amended. The bill which went on to be enacted was a partial-birth abortion ban, passing by a vote of 78 to 3. Republican Governor Huckabee signed it into law on April 1, 1997. It became effective August 1, 1997.[17] In 1997, AR HB 1351 reached a floor vote. It was another partial-birth abortion related bill introduced on January 27, 1997 by Republican Representative Hendren. It defined the procedure as "partially vaginally delivering a fetus resulting in the termination of the pregnancy of a partial birth-abortion as defined by the United States Supreme Court in any opinion issued after the effective date of this act".[17] Despite having an unconstitutional pre-Roe v. Wade abortion law, this law had not been repealed by 1998 and stated that anyone who performed an abortion could be punished with up to a year in prison and a fine up to US$1000.[17]

The state was one of twenty-three states in 2007 to have a detailed abortion-specific informed consent requirement.[18] Georgia, Michigan, Arkansas and Idaho all required in 2007 that women must be provided by an abortion clinic with the option to view an image of their fetus if an ultrasound is used prior to the abortion taking place.[19] Arkansas, Minnesota and Oklahoma all require that women seeking abortions after 20-weeks be verbally informed that the fetus may feel pain during the abortion procedure despite a Journal of the American Medical Association conclusion that pain sensors do not develop in the fetus until between weeks 23 and 30.[19] Informed consent materials about fetal pain at 20-weeks in Arkansas, Georgia and Oklahoma says, "the unborn child has the physical structures necessary to experience pain." The Journal of the American Medical Association has concluded that pain sensors do not develop in the fetus until between weeks 23 and 30.[19] In 2013, state Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) law applied to medication induced abortions and private doctor offices.[20]

A fetal heartbeat bill, banning abortion after twelve weeks, was passed on January 31, 2013 by the Arkansas Senate,[21][22] vetoed in Arkansas by Governor Mike Beebe, but, on March 6, 2013, his veto was overridden by the Arkansas House of Representatives.[22][23] A federal judge issued a temporary injunction against the Arkansas law in May 2013,[24] and in March 2014, it was struck down by federal judge Susan Webber Wright, who described the law as unconstitutional.[25]

In 2019, only 24% of the state legislators were female.[26]

Judicial history

The US Supreme Court's decision in 1973's Roe v. Wade ruling meant the state could no longer regulate abortion in the first trimester.[16]

In May 2013, a federal judged blocked the implementation of the legislation passed in March 2013.[22] On May 27, 2015, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed a lower court ruling and permanently blocked the law from being enforced.[27] In January 2016, The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case, leaving the Eighth Circuit's ruling in place.[28]

Clinic history

Between 1982 and 1992, the number of abortion clinics in the state decreased by five, going from thirteen in 1982 to eight in 1992.[17] In 2014, there were three abortion clinics in the state.[29] In 2014, 97% of the counties in the state did not have an abortion clinic. That year, 77% of women in the state aged 15 – 44 lived in a county without an abortion clinic.[30] As of 2019, there was 1 Planned Parenthood clinic in a state which 1 offered abortion services.[31]

Statistics

In the period between 1972 and 1974, there were zero recorded illegal abortion deaths in the state.[32] In 1990, 241,000 women in the state faced the risk of an unintended pregnancy.[17] In 2010, the state had zero publicly funded abortions.[33] In 2013, among white women aged 15–19, there were abortions 270, 240 abortions for black women aged 15–19, 40 abortions for Hispanic women aged 15–19, and 10 abortions for women of all other races.[34] In 2014, 38% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[35] In 2017, the state had an infant mortality rate of 8.2 deaths per 1,000 live births.[9]

| Census division and state | Number | Rate | % change 1992–1996 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

| US Total | 1,528,930 | 1,363,690 | 1,365,730 | 25.9 | 22.9 | 22.9 | –12 |

| West South Central | 127,070 | 119,200 | 120,610 | 19.6 | 18 | 18.1 | –8 |

| Arkansas | 7,130 | 6,010 | 6,200 | 13.5 | 11.1 | 11.4 | –15 |

| Louisiana | 13,600 | 14,820 | 14,740 | 13.4 | 14.7 | 14.7 | 10 |

| Oklahoma | 8,940 | 9,130 | 8,400 | 12.5 | 12.9 | 11.8 | –5 |

| Texas | 97,400 | 89,240 | 91,270 | 23.1 | 20.5 | 20.7 | –10 |

| Location | Residence | Occurrence | % obtained by out-of-state residents |

Year | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | ||||

| Arkansas | 7,130 | 13.5 | 1992 | [36] | |||||

| Arkansas | 6,010 | 11.1 | 1995 | [36] | |||||

| Arkansas | 6,200 | 11.4 | 1996 | [36] | |||||

| Arkansas | 4,024 | 7.0 | 104 | 4,253 | 7.4 | 110 | 22.2 | 2014 | [37] |

| Arkansas | 3,805 | 6.6 | 98 | 3,771 | 6.5 | 97 | 18.6 | 2015 | [38] |

| Arkansas | 3,432 | 6.0 | 90 | 3,207 | 5.6 | 84 | 16.5 | 2016 | [39] |

| ^number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44; ^^number of abortions per 1,000 live births | |||||||||

Abortion rights views and activities

Protests

Women from the state participated in marches supporting abortion rights as part of a #StoptheBans movement in May 2019.[40]

Footnotes

- According to the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade:

(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgement of the pregnant woman's attending physician. (b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health. (c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgement, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.

Likewise, Black's Law Dictionary defines abortion as "knowing destruction" or "intentional expulsion or removal".

References

- Watson, Katie (20 Dec 2019). "Why We Should Stop Using the Term "Elective Abortion"". AMA Journal of Ethics. 20: E1175-1180. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2018.1175. PMID 30585581. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Chamberlain, Pam; Hardisty, Jean (2007). "The Importance of the Political 'Framing' of Abortion". The Public Eye Magazine. 14 (1).

- "The Roberts Court Takes on Abortion". New York Times. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- Brennan 'Dehumanizing the vulnerable' 2000

- Getek, Kathryn; Cunningham, Mark (February 1996). "A Sheep in Wolf's Clothing – Language and the Abortion Debate". Princeton Progressive Review.

- "Example of "anti-life" terminology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

- Castillo, Stephanie (2014-10-03). "States With More Abortion Restrictions Hurt Women's Health, Increase Risk For Maternal Death". Medical Daily. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Mundell, E.J. (January 16, 2019). "Two-Thirds of Poor U.S. Women Can't Afford Menstrual Pads, Tampons: Study". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- Larimer, Sarah (January 8, 2016). "The 'tampon tax,' explained". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Bowerman, Mary (July 25, 2016). "The 'tampon tax' and what it means for you". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Hillin, Taryn. "These are the U.S. states that tax women for having periods". Splinter. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- "Election Results 2018: Nevada Ballot Questions 1-6". KNTV. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Brownstein, Ronald (2019-05-23). "White Women Are Helping States Pass Abortion Restrictions". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- Buell, Samuel (1991-01-01). "Criminal Abortion Revisited". New York University Law Review. 66: 1774–1831.

- Arndorfer, Elizabeth; Michael, Jodi; Moskowitz, Laura; Grant, Juli A.; Siebel, Liza (December 1998). A State-By-State Review of Abortion and Reproductive Rights. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788174810.

- "State Policy On Informed Consent for Abortion" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review. Fall 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "State Abortion Counseling Policies and the Fundamental Principles of Informed Consent". Guttmacher Institute. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- "TRAP Laws Gain Political Traction While Abortion Clinics—and the Women They Serve—Pay the Price". Guttmacher Institute. 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Parker, Suzi (January 31, 2013). "Arkansas Senate passes fetal heartbeat law to ban most abortions". Reuters. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Times, The New York. "Abortion Restrictions in States". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Bassett, Laura (March 6, 2013). "Arkansas 12-Week Abortion Ban Becomes Law". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- "Ark. 'heartbeat' abortion law blocked - Washington Times". The Washington Times.

- AP (March 15, 2014). "U.S. judge strikes Arkansas' 12-week abortion ban". USA Today. Retrieved September 20, 2014.

- "Yes, you can blame the patriarchy for these horrible abortion laws. We did the math". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- "Arkansas Human Heartbeat Protection Act (SB 134)". rewire.news. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Heartbeat Bans". rewire.news. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

In January 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case, leaving the Eighth Circuit’s ruling in place.

- Gould, Rebecca Harrington, Skye. "The number of abortion clinics in the US has plunged in the last decade — here's how many are in each state". Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- businessinsider (2018-08-04). "This is what could happen if Roe v. Wade fell". Business Insider (in Spanish). Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- https://www.plannedparenthood.org/health-center/AR

- Cates, Willard; Rochat, Roger (March 1976). "Illegal Abortions in the United States: 1972–1974". Family Planning Perspectives. 8 (2): 86. doi:10.2307/2133995. JSTOR 2133995. PMID 1269687.

- "Guttmacher Data Center". data.guttmacher.org. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "No. of abortions among women aged 15–19, by state of residence, 2013 by racial group". Guttmacher Data Center. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- "Views about abortion by state - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- "Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States, 1995-1996". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-06-15. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2017). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2014". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 66 (24): 1–48. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6624a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMID 29166366.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2018). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 67 (13): 1–45. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6713a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 30462632.

- Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2019). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 68. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1. ISSN 1546-0738.

- Bacon, John. "Abortion rights supporters' voices thunder at #StopTheBans rallies across the nation". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2019-05-25.