Acetabulum

The acetabulum /æsəˈtæbjʊləm/ (cotyloid cavity) is a concave surface of the pelvis. The head of the femur meets with the pelvis at the acetabulum, forming the hip joint.[1][2]

Structure

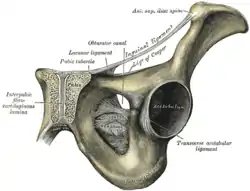

There are three bones of the os coxae (hip bone) that come together to form the acetabulum. Contributing a little more than two-fifths of the structure is the ischium, which provides lower and side boundaries to the acetabulum. The ilium forms the upper boundary, providing a little less than two-fifths of the structure of the acetabulum. The rest is formed by the pubis, near the midline.

It is bounded by a prominent uneven rim, which is thick and strong above, and serves for the attachment of the acetabular labrum, which reduces its opening, and deepens the surface for formation of the hip joint. At the lower part of the acetabulum is the acetabular notch, which is continuous with a circular depression, the acetabular fossa, at the bottom of the cavity of the acetabulum. The rest of the acetabulum is formed by a curved, crescent-moon shaped surface, the lunate surface, where the joint is made with the head of the femur. Its counterpart in the pectoral girdle is the glenoid fossa.[3]

The acetabulum is also home to the acetabular fossa, an attachment site for the ligamentum teres, a triangular, somewhat flattened band implanted by its apex into the antero-superior part of the fovea capitis femoris. The notch is converted into a foramen by the transverse acetabular ligament; through the foramen nutrient vessels and nerves enter the joint. This is what holds the head of the femur securely in the acetabulum.[1]

The well-fitting surfaces of the femoral head and acetabulum, which face each other, are lined with a layer of slippery tissue called articular cartilage, which is lubricated by a thin film of synovial fluid. Friction inside a normal hip is less than one-tenth that of ice gliding on ice.[4][5]

Blood supply

The acetabular branch of the obturator artery supplies the acetabulum through the acetabular notch. The pubic branches supply the pelvic surface of the acetabulum. Deep branches of the superior gluteal artery supply the superior region and the inferior gluteal artery supplies the postero-inferior region.[6]

Reptiles and birds

In reptiles and birds, the acetabula are deep sockets. Organisms in the dinosauria clade are defined by a perforate acetabulum, which can be thought of as a "hip-socket". The perforate acetabulum is a cup-shaped opening on each side of the pelvic girdle formed where the ischium, ilium, and pubis all meet, and into which the head of the femur inserts.[7][8] The orientation and position of the acetabulum is one of the main morphological traits that caused dinosaurs to walk in an upright posture with their legs directly underneath their bodies. In a relatively small number of dinosaurs, particularly ankylosaurians (e.g. Texasetes pleurohalio), an imperforate acetabulum is present, which is not an opening, but instead resembles a shallow concave depression on each side of the pelvic girdle.

Development

In infants and children, a 'Y'-shaped epiphyseal plate called the triradiate cartilage joins the ilium, ischium, and pubis. This cartilage ossifies as the child grows.[9]

History

The word acetabulum literally means "little vinegar cup". It was the Latin word for a small vessel for serving vinegar. The word was later also used as a unit of volume.

Additional images

Right hip bone. External surface.

Right hip bone. External surface. Plan of ossification of the hip bone.

Plan of ossification of the hip bone.

Symphysis pubis exposed by a coronal section.

Symphysis pubis exposed by a coronal section. Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis.

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis. Hip-joint, front view.

Hip-joint, front view. Capsule of hip-joint (distended). Posterior aspect.

Capsule of hip-joint (distended). Posterior aspect. Structures surrounding right hip-joint.

Structures surrounding right hip-joint. Acetabulum

Acetabulum Hip joint. Lateral view. Acetabulum

Hip joint. Lateral view. Acetabulum Hip joint. Lateral view. Acetabulum

Hip joint. Lateral view. Acetabulum

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 237 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Field RE, Rajakulendran K (2011). "The labro-acetabular complex". J Bone Joint Surg Am. 94 (Suppl 2): 22–27. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01710. PMID 21543684.

- Griffiths EJ, Khanduja V (2012). "Hip arthroscopy: evolution, current practice and future developments". Int Orthop. 36 (6): 1115–1121. doi:10.1007/s00264-011-1459-4. PMC 3353094. PMID 22371112.

- Petersilge C (2005). "Imaging of the acetabular labrum". Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 13 (4): 641–52. doi:10.1016/j.mric.2005.08.015. PMID 16275573.

- Balakumar J. "Hip Dysplasia in the Child, Adolescent and Adult". jitbalakumar.com.au. Archived from the original on 2013-04-25. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- OrthoInfo (September 2010). "Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI)". orthoinfo.aaos.org. the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- Itokazu M, Takahashi K, Matsunaga T, Hayakawa D, Emura S, Isono H, Shoumura S (1997). "A study of the arterial supply of the human acetabulum using a corrosion casting method". Clin Anat. 10 (2): 77–81. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1997)10:2<77::AID-CA1>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 9058012.

- Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

- Smith, Dave. "Dinosauria: Morphology". UC Berkeley. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, A. M. R. (2013-02-13). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451119459.

- Ruiz Santiago, Fernando; Santiago Chinchilla, Alicia; Ansari, Afshin; Guzmán Álvarez, Luis; Castellano García, Maria del Mar; Martínez Martínez, Alberto; Tercedor Sánchez, Juan (2016). "Imaging of Hip Pain: From Radiography to Cross-Sectional Imaging Techniques". Radiology Research and Practice. 2016: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2016/6369237. ISSN 2090-1941. PMC 4738697. PMID 26885391. (Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

External links

| Look up acetabulum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Acetabulum. |

- Anatomy photo:17:01-0501 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Major Joints of the Lower Extremity: Hip joint"

- Anatomy photo:43:os-0407 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Female Pelvis: Articulated bones of pelvis"