Pubis (bone)

In vertebrates, the pubic bone is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three main bones making up the pelvis. The left and right pubic bones are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior ramus, and a body.

| Pubic bone | |

|---|---|

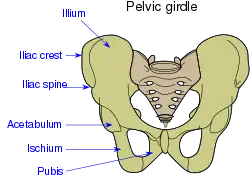

Pelvic girdle | |

Male pelvis | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Pelvis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Os pubis |

| MeSH | D011630 |

| TA98 | A02.5.01.301 |

| TA2 | 1346 |

| FMA | 16595 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Structure

The pubic bone is made up of a body, superior ramus, and inferior ramus (Latin: branch). The left and right hip bones join at the pubic symphysis. It is covered by a layer of fat, which is covered by the mons pubis. The pubis is the lower limit of the suprapubic region. In the female, the pubic bone is anterior to the urethral sponge.

Body

The body forms the wide, strong, middle and flat part of the pubic bone. The bodies of the left and right pubic bones join together at the pubic symphysis.[1] The rough upper edge is the pubic crest,[2] ending laterally in the pubic tubercle. This tubercle, found roughly 3 cm from the pubic symphysis, is a distinctive feature on the lower part of the abdominal wall; important when localizing the superficial inguinal ring and the femoral canal of the inguinal canal.[3] The inner surface of the body forms part of the wall of the lesser pelvis and joints to the origin of a part of the obturator internus muscle.

Superior pubic ramus

The superior pubic ramus is the upper of the two rami. It forms the upper edge of the obturator foramen.[4] It extends from the body to the median plane where it joins with the ramus of the opposite side. It consists of an inner flattened part and a narrow outer prismoid portion.

Medial surface

Surfaces

- The anterior surface is rough, directed downward and outward, and serves for the origin of various muscles. The Adductor longus arises from the upper and medial angle, immediately below the crest; lower down, the obturator externus, the adductor brevis, and the upper part of the gracilis take origin.

- The posterior surface, convex from above downward, concave from side to side, is smooth, and forms part of the anterior wall of the pelvis. It gives origin to the levator ani and Obturator internus, and attachment to the puboprostatic ligaments and to a few muscular fibers prolonged from the bladder.

Borders

- The upper border presents a prominent tubercle, the pubic tubercle (pubic spine), which projects forward; the inferior crus of the subcutaneous inguinal ring (external abdominal ring), and the inguinal ligament (Poupart’s ligament) are attached to it.

Passing upward and laterally from the pubic tubercle is a well-defined ridge, forming a part of the pectineal line which marks the brim of the lesser pelvis: to it are attached a portion of the inguinal falx (conjoined tendon of obliquus internus and transversus), the lacunar ligament (Gimbernat’s ligament), and the reflected inguinal ligament (triangular fascia).

Medial to the pubic tubercle is the crest, which extends from this process to the medial end of the bone. It affords attachment to the inguinal falx, and to the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis.

The point of junction of the crest with the medial border of the bone is called the angle; to it, as well as to the symphysis, the superior crus of the subcutaneous inguinal ring is attached.

The medial border is articular; it is oval, and is marked by eight or nine transverse ridges, or a series of nipple-like processes arranged in rows, separated by grooves; they serve for the attachment of a thin layer of cartilage, which intervenes between it and the interpubic fibrocartilaginous lamina.

The lateral border presents a sharp margin, the obturator crest, which forms part of the circumference of the obturator foramen and affords attachment to the obturator membrane.

Lateral portion

Surfaces

- The superior surface presents a continuation of the pectineal line, already mentioned as commencing at the pubic tubercle. In front of this line, the surface of bone is triangular in form, wider laterally than medially, and is covered by the Pectineus. The surface is bounded, laterally, by a rough eminence, the iliopectineal eminence, which serves to indicate the point of junction of the ilium and pubis, and below by a prominent ridge which extends from the acetabular notch to the pubic tubercle.

- The inferior surface forms the upper boundary of the obturator foramen, and presents, laterally, a broad and deep, oblique groove, for the passage of the obturator vessels and nerve; and medially, a sharp margin, the obturator crest, forming part of the circumference of the obturator foramen, and giving attachment to the obturator membrane.

- The posterior surface constitutes part of the anterior boundary of the lesser pelvis. It is smooth, convex from above downward, and affords origin to some fibers of the obturator internus.

Inferior pubic ramus

The inferior pubic ramus is a part of the pelvis and is thin and flat. It passes laterally and downward from the medial end of the superior ramus; it becomes narrower as it descends and joins with the inferior ramus of the ischium below the obturator foramen.

Surfaces

- Its anterior surface is rough, for the origin of muscles—the Gracilis along its medial border, a portion of the Obturator externus where it enters into the formation of the obturator foramen, and between these two, the Adductores brevis and magnus, the former being the more medial.

- The posterior surface is smooth, and gives origin to the Obturator internus, and, close to the medial margin, to the Constrictor urethrae.

Borders

- In the female pelvis, the medial border is thick, rough, and everted, and presents two ridges, separated by an intervening space. The ridges extend downwards, and are continuous with similar ridges on the inferior ramus of the ischium;

- to the external ridge is attached the fascia of Colles

- to the internal ridge is attached the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm

- The lateral border is thin and sharp, forms part of the circumference of the obturator foramen, and gives attachment to the obturator membrane.

Other animals

Mammals

Non-placental mammals possess osteological projections of the pubis known as epipubic bones. These evolved first among derived cynodonts, and evolved as a means of support for muscules flexing the thigh, facilitating the development of an erect gait.[5] However, these prevent the expansion of the torso, preventing pregnancy and forcing the animal to give birth to larval young (the modern marsupial "joeys" and monotreme "puggles").[6]

Placentals are unique among all mammals, including other eutherians, in having lost epipubic bones and having been able to develop proper pregnancy. In some groups, remnants of these pre-pubic bones can be found as os penises.[7]

Dinosaurs

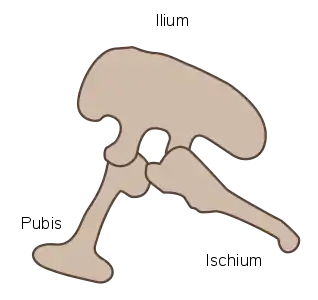

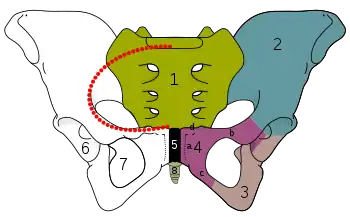

The clade Dinosauria is divided into the Saurischia and Ornithischia based on hip structure, including importantly that of the pubis.[8] An opisthopubic pelvis is a condition where the pubic bone extends back towards the tail of the animal, a trait that is also present in birds.[9] In a propubic pelvis, however, the pubic bone extends forward towards the head of the animal, as can be seen in the typical saurischian pelvic structure pictured below. The acetabulum, which can be thought of as a "hip-socket", is an opening on each side of the pelvic girdle formed where the ischium, ilium, and pubis all meet, and into which the head of the femur inserts. The orientation and position of the acetabulum is one of the main morphological traits that caused dinosaurs to walk in an upright posture with their legs directly underneath their bodies.[10] The prepubic process is a bony extension of the pubis that extends forward from the hip socket and toward the front of the animal. This adaptation is thought to have played a role in supporting the abdominal muscles.

Ornithischian pelvic structure (left side)

Ornithischian pelvic structure (left side) Saurischian pelvic structure (left side).

Saurischian pelvic structure (left side).

Additional images

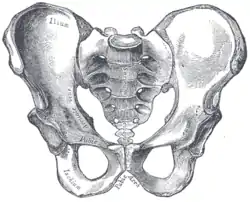

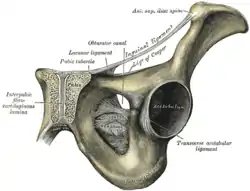

The sacrum and pelvic bone, with parts labelled. The pubic bone consists of the body and superior pubic ramus (4), and the inferior pubic ramus (3), which join together at the pubic symphysis. The gap between them is the obturator foramen.

The sacrum and pelvic bone, with parts labelled. The pubic bone consists of the body and superior pubic ramus (4), and the inferior pubic ramus (3), which join together at the pubic symphysis. The gap between them is the obturator foramen. Right hip bone. External surface.

Right hip bone. External surface. Right hip bone. Internal surface.

Right hip bone. Internal surface. Plan of ossification of the hip bone.

Plan of ossification of the hip bone. Symphysis pubis exposed by a coronal section.

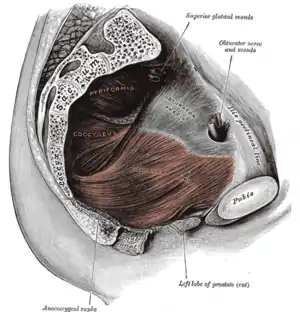

Symphysis pubis exposed by a coronal section. Left levator ani from within.

Left levator ani from within. The obturator externus.

The obturator externus. Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis.

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis. Pubis

Pubis

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 236 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- "Definition: body of pubis from Online Medical Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- "crista pubica" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Bojsen-Møller, Finn (2000). Rörelseapparatens anatomi (in Swedish). Liber. p. 239. ISBN 91-47-04884-0.

- "Definition: superior pubic ramus from Online Medical Dictionary". Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- White, T.D. (August 9, 1989). "An analysis of epipubic bone function in mammals using scaling theory". Journal of Theoretical Biology 139 (3): 343–57. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(89)80213-9. PMID 2615378.

- Michael L. Power, Jay Schulkin. The Evolution Of The Human Placenta. pp. 68–.

- Frederick S. Szalay (11 May 2006). Evolutionary History of the Marsupials and an Analysis of Osteological Characters. Cambridge University Press. pp. 293–. ISBN 978-0-521-02592-8.

- Seeley, H.G. (1888). "On the classification of the fossil animals commonly named Dinosauria." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 43: 165-171.

- Barsbold, R., (1979) Opisthopubic pelvis in the carnivorous dinosaurs. Nature. 279, 792-793

- Martin, A.J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs. Second Edition. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing. pg. 299-300. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pubis (bone). |

| Look up pubis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Anatomy photo:44:st-0713 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "The Male Pelvis: Hip Bone"