Albanian alphabet

The Albanian alphabet (Albanian: alfabeti shqip) is a variant of the Latin alphabet used to write the Albanian language. It consists of 36 letters:[1]

| Capital letters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | B | C | Ç | D | Dh | E | Ë | F | G | Gj | H | I | J | K | L | Ll | M | N | Nj | O | P | Q | R | Rr | S | Sh | T | Th | U | V | X | Xh | Y | Z | Zh |

| Lower case letters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | c | ç | d | dh | e | ë | f | g | gj | h | i | j | k | l | ll | m | n | nj | o | p | q | r | rr | s | sh | t | th | u | v | x | xh | y | z | zh |

| IPA value | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | b | t͡s | t͡ʃ | d | ð | ɛ | ə | f | ɡ | ɟ͡ʝ | h | i | j | k | l | ɫ | m | n | ɲ | ɔ | p | c͡ç | ɾ | r | s | ʃ | t | θ | u | v | d͡z | d͡ʒ | y | z | ʒ |

Note: The vowels are shown in bold. ![]() Listen to the pronunciation of the 36 letters.

Listen to the pronunciation of the 36 letters.

History

The earliest known mention of Albanian writings comes from a French Catholic church document from 1332.[2][3] Written either by archbishop Guillaume Adam or the monk Brocardus Monacus the report notes that Licet Albanenses aliam omnino linguam a latina habeant et diversam, tamen litteram latinam habent in usu et in omnibus suis libris ("Though the Albanians have a language entirely their own and different from Latin, they nevertheless use Latin letters in all their books").[2][3] Scholars warn that this could mean Albanians also wrote in the Latin language, not necessarily just Albanian with a Latin script.[4]

The history of the later Albanian alphabet is closely linked with the influence of religion among Albanians. The writers from the North of Albania used Latin letters under the influence of the Catholic Church, those from the South of Albania under the Greek Orthodox church used Greek letters, while others used Arabic letters under the influence of Islam. There were also attempts for an original Albanian alphabet in the period of 1750–1850. The current alphabet in use among Albanians is one of the two variants approved in the Congress of Monastir held by Albanian intellectuals from 14 to 22 November 1908, in Monastir (Bitola, North Macedonia).

Alphabet used in early literature

The first certain document in Albanian is the "Formula e pagëzimit" (1462) (baptismal formula), issued by Pal Engjëlli (1417–1470); it was written in Latin characters.[5]:3 It was a simple phrase that was supposed to be used by the relatives of a dying person if they could not make it to churches during the troubled times of the Ottoman invasion.

Also, the five Albanian writers of the 16th and 17th centuries (Gjon Buzuku, Lekë Matrënga, Pjetër Budi, Frang Bardhi and Pjetër Bogdani) who form the core of early Albanian literature, all used a Latin alphabet for their Albanian books; this alphabet remained in use by writers in northern Albania until the beginning of the 20th century.

The Greek intellectual Anastasios Michael, in his speech to the Berlin Academy (c. 1707) mentions an Albanian alphabet produced "recently" by Kosmas from Cyprus, bishop of Dyrrachium. It is assumed that this is the alphabet used later for the "Gospel of Elbasan". Anastasios calls Kosmas the "Cadmus of Albania".[6]

National awakening 19th-century endeavours

In 1857 Kostandin Kristoforidhi, an Albanian scholar and translator, drafted in Istanbul, Ottoman Empire, a Memorandum for the Albanian language. He then went to Malta, where he stayed until 1860 in a Protestant seminary, finishing the translation of The New Testament in the Tosk and Gheg dialects. He was helped by Nikolla Serreqi from Shkodër with the Gheg version of the New Testament. Nikolla Serreqi was also the propulsor for the use of the Latin script for the translation of the New Testament, which had already been used by the early writers of the Albanian literature; Kristoforidhi enthusiastically embraced the idea of a Latin alphabet.[7]

In November 1869, a Commission for the Alphabet of the Albanian Language was gathered in Istanbul. One of its members was Kostandin Kristoforidhi and the main purpose of the commission was the creation of a unique alphabet for all the Albanians. In January 1870 the commission ended its work of the standardization of the alphabet, which was mainly in Latin letters. A plan on the creation of textbooks and spread of Albanian schools was drafted. However this plan was not realized, because the Ottoman government would not finance the expenses for the establishment of such schools.[8]

Although this commission had gathered and delivered an alphabet in 1870, the writers from the North still used the Latin-based alphabet, whereas in southern Albania writers used mostly the Greek letters. In southern Albania, the main activity of Albanian writers consisted in translating Greek Orthodox religious texts, and not in forming any kind of literature which could form a strong tradition for the use of Greek letters. As the albanologist Robert Elsie has written:[9]

The predominance of Greek as the language of Christian education and culture in southern Albania and the often hostile attitude of the Orthodox church to the spread of writing in Albanian made it impossible for an Albanian literature in Greek script to evolve. The Orthodox church, as the main vehicle of culture in the southern Balkans, while intent on spreading Christian education and values, was never convinced of the utility of writing in the vernacular as a means of converting the masses, as the Catholic church in northern Albania had been, to a certain extent, during the Counter-Reformation. Nor, with the exception of the ephemeral printing press in Voskopoja, did the southern Albanians ever have at their disposal publishing facilities like those available to the clerics and scholars of Catholic Albania in Venice and Dalmatia. As such, the Orthodox tradition in Albanian writing, a strong cultural heritage of scholarship and erudition, though one limited primarily to translations of religious texts and to the compilation of dictionaries, was to remain a flower which never really blossomed.

The turning point was the aftermath of the League of Prizren (1878) events when in 1879 Sami Frashëri and Naim Frashëri formed the Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings. Sami Frashëri, Koto Hoxhi, Pashko Vasa and Jani Vreto created an alphabet. This was based on the principle of "one sound one letter" (although the revision of 1908 replaced the letter ρ by the rr digraph to avoid confusion with p). This was called the "Istanbul alphabet" (also "Frashëri alphabet"). In 1905 this alphabet was in widespread use in all Albanian territory, North and South, including Catholic, Muslim and Orthodox areas.

One year earlier, in 1904 had been published the Albanian dictionary (Albanian: Fjalori i Gjuhës Shqipe) of Kostandin Kristoforidhi, after the author's death. The dictionary had been drafted 25 years before its publication and was written in the Greek alphabet.[10]

The so-called Bashkimi alphabet was designed by the Society for the Unity of the Albanian Language for being written on a French typewriter and includes no diacritics other than é (compared to ten graphemes of the Istanbul alphabet which were either non-Latin or had diacritics).

Congress of Manastir

In 1908, the Congress of Manastir was held by Albanian intellectuals in Bitola, Ottoman Empire, modern-day Republic of North Macedonia. The Congress was hosted by the Bashkimi ("unity") club, and prominent delegates included Gjergj Fishta, Ndre Mjeda, Mit'hat Frashëri, Sotir Peçi, Shahin Kolonja, and Gjergj D. Qiriazi. There was much debate and the contending alphabets were Istanbul, Bashkimi and Agimi. However, the Congress was unable to make a clear decision and opted for a compromise solution of using both the widely used Istanbul, with minor changes, and a modified version of the Bashkimi alphabet. Usage of the alphabet of Istanbul declined rapidly and it was essentially extinct over the following decades.

During 1909 and 1910 there were movements by Young Turks supporters to adopt an Arabic alphabet, as they considered the Latin script to be un-Islamic. In Korçë and Gjirokastër, demonstrations took place favoring the Latin script, and in Elbasan, Muslim clerics led a demonstration for the Arabic script, telling their congregations that using the Latin script would make them infidels. In 1911, the Young Turks dropped their opposition to the Latin script; finally, the Latin Bashkimi alphabet was adopted, and is still in use today.

The modifications to the Bashkimi alphabet were made to include characters used in the Istanbul and Agimi alphabets. Ç was chosen over ch since c with cedilla could be found on every typewriter, given its use in French. Other changes were more esthetic and as a way to combine the three scripts.

| Alphabetical order: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 |

| IPA: | [a ɑ ɒ] | [b] | [ts] | [tʃ] | [d] | [ð] | [e ɛ] | [ə] | [f] | [g] | [ɟ] | [h ħ] | [i] | [j] | [k q] | [l] | [ɫ] | [m] | [n] | [ɲ] | [o ɔ] | [p] | [c tɕ] | [ɾ] | [r] | [s] | [ʃ] | [t] | [θ] | [u] | [v] | [dz] | [dʒ] | [y] | [z] | [ʒ] |

| Bashkimi alphabet: | A a | B b | Ts ts | Ch ch | D d | Dh dh | É é | E e | F f | G g | Gh gh | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | Ll ll | M m | N n | Gn gn | O o | P p | C c | R r | Rr rr | S s | Sh sh | T t | Th th | U u | V v | Z z | Zh zh | Y y | X x | Xh xh |

| Istanbul alphabet: | A a | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | Б δ | E ε | ♇ e | F f | G g | Γ γ | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | Λ λ | M m | N n | И ŋ | O o | Π p | Q q | R r | Ρ ρ | S s | Ϲ σ | T t | Θ θ | U u | V v | X x | X̦ x̦ | Y y | Z z | Z̧ z̧ |

| Manastir alphabet (modified Bashkimi, current alphabet): | A a | B b | C c | Ç ç | D d | Dh dh | E e | Ë ë | F f | G g | Gj gj | H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | Ll ll | M m | N n | Nj nj | O o | P p | Q q | R r | Rr rr | S s | Sh sh | T t | Th th | U u | V v | X x | Xh xh | Y y | Z z | Zh zh |

A second congress at Monastir (Bitola) was held in April 1910, which confirmed the decision taken in the first congress of Monastir. After Albanian independence in 1912, there were two alphabets in use. Following the events of the Balkan wars and World War I, the Bashkimi variant dominated. The Bashkimi alphabet is at the origin of the official alphabet of the Albanian language in use today.

Other alphabets used for written Albanian

The modern Latin-based Albanian alphabet is the result of long evolution. Before the creation of the unified alphabet, Albanian was written in several different alphabets, with several sub-variants:

Derived alphabets

Latin-derived alphabet

- The Latin script, using various conventions:

- The oldest surviving document with Albanian text is from the 15th century and written in the Latin script. Early Albanian writers such as Gjon Buzuku, Pjetër Bogdani, Pjetër Budi, and Frang Bardhi also used a Latin-based script, adding Greek characters to represent extra sounds.

- A Catholic alphabet used by Arbëreshë (Italo-Albanians).

- The Istanbul alphabet, created by Sami Frashëri, combining Latin and Greek. This became widely used as it was also adopted by the Istanbul Society for the Printing of Albanian Writings, which in 1879 printed Alfabetare, the first Albanian abecedarium.

- Bashkimi, developed by the Albanian literary society Bashkimi (Unity) in Shkodër with the help of Catholic clergy and Franciscans aiming at more simplicity than its forerunners. It used digraphs for unique sounds of the Albanian language. It resembles the current alphabet with the differences being the use of ch for ç, c for q, ts for c, é for e, e for ë, gh for gj, gn for nj, and z/zh have swapped places with x/xh.

- Agimi, developed by the Agimi ("Dawn") Literary Society in 1901, and spearheaded by Ndre Mjeda. It made use of diacritics instead of digraphs used by Bashkimi.

Greek-derived alphabet

- The Greek alphabet; used to write Tosk starting in about 1500 (Elsie, 1991). The printing press at Voskopojë published several Albanian texts in Greek script during the 18th century (Macrakis, 1996).

- The Ottoman Turkish alphabet, favored by Muslims. Last version called Elifbaja shqip was published by scholar and writer Rexhep Voka, a prominent figure of the Albanian National Awakening.

Arabic-derived alphabet

- The Arabic alphabet; a primer was published in 1861 in Constantinople by Mullah Daut Boriçi.[11]

Original alphabets

- The Elbasan script (18th century); used to write the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript. Widely thought to be the work of Gregory of Durrës. According to Robert Elsie, "The alphabet of the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript is quite well suited to the Albanian language. Indeed, on the whole, one might regard it as better suited than the present-day Albanian alphabet, based on a Latin model. The Elbasan alphabet utilizes one character per phoneme, with the exception of n, for which there are two characters, and g, for which there are three characters (two of which being restricted to specific Greek loanwords). The distinction between Albanian r and rr and between l and ll is created by a dot over the character. A dot over a d creates an nd. A spiritus lenis plus acute above the line, as in Greek, seems to be utilized on a sporadic basis to indicate word or phrase stress. On the whole, the writing system utilized in the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript is clear, relatively precise, and appears to be well thought out by its inventor."[12]

- Undeciphered Script from the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript. On the front page of the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript itself is a drawing and about a dozen words, perhaps personal names, written in a script which differs completely from that of the rest of the manuscript. This writing system has as yet to be deciphered, although Elbasan scholar Dhimitër Shuteriqi (b. 1915) has made an attempt to read it.[12]

- The Todhri script (18th century), attributed to Todhri Haxhifilipi. The Todhri alphabet was discovered by Johann Georg von Hahn (1811–1869), Austrian consul in Janina and the father of Albanian Studies. Hahn published what he regarded as 'the original' Albanian alphabet in his monumental Albanesische Studien (Jena 1854) and saw in it a derivative of ancient Phoenician script. The study of this alphabet was subsequently taken up by Leopold Geitler (1847–1885) who regarded Todhri script as derived primarily from Roman cursive, and by the Slovenian scholar Rajko Nahtigal(1877–1958). The Todhri alphabet is a complex writing system of fifty-two characters which was used sporadically for written communication in and around Elbasan from the late eighteenth century on. It does not conform adequately to the Albanian language, certainly not as well as the alphabet of the Elbasan Gospel Manuscript, to which it shows no relation[12]

- Another original script is found in Codex of Berat (not to be confused with Codex Beratinus I and II). This 154-page manuscript, now preserved in the National Library of Tiranë, is in actual fact a simple paper manuscript and must not be envisaged as an illuminated parchment 'codex' in the Western tradition. It seems to have been the work of at least two hands and to have been written between the years 1764 and 1798. The manuscript is commonly attributed to one Constantine of Berat (c. 1745 – c. 1825), known in Albanian as Kostandin Berati or Kostë Berati, who is thought to have been an Orthodox monk and writer from Berat. Constantine of Berat is reported to have possessed the manuscript from 1764 to 1822, although there is no indication that he was its author. The Codex of Berat contains various and sundry texts in Greek and Albanian: biblical and Orthodox liturgical texts in Albanian written in the Greek alphabet, all of them no doubt translated from Greek or strongly influenced by Greek models; a forty-four-line Albanian poem with the corresponding Greek text known as Zonja Shën Mëri përpara kryqësë (The Virgin Mary before the cross); two Greek-Albanian glossaries comprising a total of 1,710 entries; various religious notes; and a chronicle of events between 1764 and 1789 written in Greek.

- On page 104 of the codex, we find two lines of Albanian written in an original alphabet of 37 letters, influenced, as it would seem, by Glagolitic script. On page 106, the author also gives an overview of the writing system he created. It, too, is not well devised and does not seem to occur anywhere else.[12]

- The Veso Bey alphabet, another original alphabet by Veso bey, who is one of the most prominent chiefs of Gjirokastër, from the family of Alizot Pasha. Veso Bey learned it in his youth from an Albanian hodja as a secret script which his family inherited, and used it himself for correspondence with his relatives.[12][13][14]

- Vellara script was used in southern Albania, named after the Greek doctor, lyricist and writer Ioannis Vilaras (Alb: Jan Vellara). The son of a doctor, Vilaras studied medicine in Padua in 1789 and later lived in Venice. In 1801, he became a physician to Veli, son of the infamous Ali Pasha Tepelena (1741–1822). Vilaras is remembered primarily as a modern Greek poet and does not seem to have been a native Albanian speaker at all. He is the author of eighty-six pages of bilingual grammatical notes, dated 1801, which were designed no doubt to teach other Greek-speakers Albanian. The Albanian in question is a Tosk dialect written in an original alphabet of thirty letters based on Latin and to a lesser extent on Greek. The manuscript of the work was donated to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris (supplément grec 251, f. 138-187) in 1819 by François Pouqueville (1770–1839), French consul in Janina during the reign of Ali Pasha Tepelena . Pouqueville was aware of the value of the work, noting: "Je possède un manuscrit, une grammaire grecque vulgaire et schype qui pourrait être utile aux philologues", but chose not to publish it in his travel narratives. Appendixed to the grammatical notes is also a letter dated 30 October 1801, written in Albanian in Vellara's handwriting from the village of Vokopolë, south of Berat, where the physician had been obliged to follow Veli during the latter's military campaign against Ibrahim of Berat. Part of the manuscript is also a list of proverbs, both in modern Greek and Albanian.[15]

- The Vithkuqi alphabet (1844). From 1824 to 1844, Naum Veqilharxhi developed and promoted a 33-letter alphabet which he had printed in an eight-page Albanian spelling book in 1844. This little spelling book was distributed throughout southern Albania, from Korçë to Berat, and was received, as it seems, with a good deal of enthusiasm. In the following year, 1845, the booklet was augmented to forty-eight pages in a now equally rare second edition entitled Faré i ri abétor shqip per djélm nismetore (A very new Albanian spelling book for elementary schoolboys). However, the resonance of this original alphabet, which reminds one at first glance of a type of cursive Armenian, was in fact limited, due in part to the author's premature death one year later and in part no doubt to financial and technical considerations. In the mid-nineteenth century, when publishing was making great strides even in the Balkans, a script requiring a new font for printing would have resulted in prohibitive costs for any prospective publisher. As such, although reasonably phonetic and confessionally neutral, the Veqilharxhi alphabet never took hold.[16]

Older versions of the alphabet in Latin characters

Before the standardisation of the Albanian alphabet, there were several ways of writing the sounds peculiar to Albanian, namely ⟨c⟩, ⟨ç⟩, ⟨dh⟩, ⟨ë⟩, ⟨gj⟩, ⟨ll⟩, ⟨nj⟩, ⟨q⟩, ⟨rr⟩, ⟨sh⟩, ⟨th⟩, ⟨x⟩, ⟨xh⟩, ⟨y⟩, ⟨z⟩ and ⟨zh⟩. Also, ⟨j⟩ was written in more than one way.

- ⟨c⟩, ⟨ç⟩, ⟨k⟩, and ⟨q⟩

The earliest Albanian sources were written by people educated in Italy, as a consequence, the value of the letters were similar to those of the Italian alphabet. The present-day c was written with a ⟨z⟩, and the present-day ç was written as ⟨c⟩ as late as 1895. Conversely, the present-day k was written as ⟨c⟩ until 1868. c was also written as ⟨ts⟩ (Reinhold 1855 and Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨tz⟩ (Rada 1866) and ⟨zz⟩. It was first written as ⟨c⟩ in 1879 by Frashëri but also in 1908 by Pekmezi. ç was also written as ⟨tz⟩ (Leake 1814), ⟨ts̄⟩ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨ci⟩ (Rada 1866), ⟨tš⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨tç⟩ (Dozon 1878), ⟨č⟩ (by Agimi) and ⟨ch⟩ (by Bashkimi). ç itself was first used by Frasheri (1879).

The present-day q was variously written as ⟨ch⟩, ⟨chi⟩, ⟨k⟩, ⟨ky⟩, ⟨kj⟩, k with dot (Leake 1814) k with overline (Reinhold 1855), k with apostrophe (Miklosich 1870), and ⟨ḱ⟩ (first used by Lepsius 1863). ⟨q⟩ was first used in Frashëri's Stamboll mix-alphabet in 1879 and also in the Grammaire albanaise of 1887.

- ⟨dh⟩ and ⟨th⟩

The present-day dh was originally written with a character similar to the Greek xi (ξ). This was doubled (ξξ) to write 'th'. These characters were used as late as 1895. Leake first used ⟨dh⟩ and ⟨th⟩ in 1814. dh was also written using the Greek letter delta (δ), while Alimi used ⟨đ⟩ and Frasheri used a ⟨d⟩ with a hook on the top stem of the letter.

- ⟨ë⟩

This letter was not usually differentiated from ⟨e⟩, but when it was, it was usually done by means of diacritics: ⟨ė⟩ (Bogdani 1685, da Lecce 1716 and Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨e̊⟩ (Lepsius 1863), ⟨ẹ̄⟩ (Miklosich 1870) or by new letters ⟨ö⟩ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨υ⟩ (Rada 1866), ⟨œ⟩ (Dozon 1878), ⟨ε⟩ (Meyer 1888 and 1891, note Frasheri used ⟨ε⟩ for ⟨e⟩, and ⟨e⟩ to write ⟨ë⟩; the revision of 1908 swapped these letters) and ⟨ə⟩ (Alimi). Rada first used ⟨ë⟩ in 1870.

- ⟨gj⟩ and ⟨g⟩

These two sounds were not usually differentiated. They were variously written as ⟨g⟩, ⟨gh⟩ and ⟨ghi⟩. When they were differentiated, g was written as ⟨g⟩ or (by Liguori 1867) as ⟨gh⟩, while gj was written as ⟨gi⟩ (Leake 1814), ⟨ḡ⟩ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨ǵ⟩ (first used by Lepsius 1863), ⟨gy⟩ (Dozon 1878) and a modified ⟨g⟩ (Frasheri). The Grammaire albanaise (1887) first used gj, but it was also used by Librandi (1897). Rada (1866) used ⟨g⟩, ⟨gh⟩, ⟨gc⟩, and ⟨gk⟩ for g, and ⟨gki⟩ for ⟨gj⟩.

- ⟨h⟩

The older versions of the Albanian alphabet differentiated between two “h” sounds, one for [h] one for the Voiceless velar fricative [x]. The second sound was written as ⟨h⟩, ⟨kh⟩, ⟨ch⟩, and Greek khi ⟨χ⟩.

- ⟨j⟩

This sound was most commonly written as ⟨j⟩, but some authors (Leake 1814, Lepsius 1863, Kristoforidis 1872, Dozon 1878) wrote this as ⟨y⟩.

- ⟨ll⟩ and ⟨l⟩

Three “l” sounds were distinguished in older Albanian alphabets, represented by IPA as /l ɫ ʎ/. l /l/ was written as ⟨l⟩. ll /ɫ/ was written as ⟨λ⟩, italic ⟨l⟩, ⟨lh⟩ and ⟨ł⟩. Blanchi (1635) first used ll. /ʎ/ was written as ⟨l⟩, ⟨li⟩, ⟨l’⟩ (Miklosich 1870 and Meyer 1888 and 1891), ⟨ĺ⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨lh⟩, ⟨gl⟩, ⟨ly⟩ and ⟨lj⟩.

- ⟨nj⟩

This sound was most commonly written as ⟨gn⟩ in Italian fashion. It was also written as italic ⟨n⟩ (Leake 1814), ⟨n̄⟩ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨ń⟩ (first used by Lepsius 1863), ⟨ṅ⟩ (Miklosich 1870), ⟨ñ⟩ (Dozon 1878). The Grammaire albanaise (1887) first used nj.

- ⟨rr⟩

Blanchi first used ⟨rr⟩ to represent this sound. However, also used were Greek rho (ρ) (Miklosich 1870), ⟨ṙ⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨rh⟩ (Dozon 1878 and Grammaire albanaise 1887), ⟨r̄⟩ (Meyer 1888 and 1891), ⟨r̀⟩ (Alimi) and ⟨p⟩ (Frasheri, who used a modified ⟨p⟩ for [p]).

- ⟨sh⟩ and ⟨s⟩

These two sounds were not consistently differentiated in the earliest versions of the Albanian alphabet. When they were differentiated, s was represented by ⟨s⟩ or ⟨ss⟩, while sh was represented by ⟨sc⟩, ⟨ſc⟩, ⟨s̄⟩ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨ç⟩ (Dozon 1878) and ⟨š⟩. sh was first used by Rada in 1866.

- ⟨x⟩

Frasheri first used ⟨x⟩ to represent this sound. Formerly, it was written variously as ⟨ds⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨dz⟩, ⟨z⟩, and ⟨zh⟩.

- ⟨xh⟩

The Grammaire albanaise (1887) first used ⟨xh⟩. Formerly, it was written variously as ⟨gi⟩, ⟨g⟩, ⟨dš⟩ (Kristoforidis 1872), ⟨dž⟩, ⟨x⟩ and ⟨zh⟩.

- ⟨y⟩

This sound was written as ⟨y⟩ in 1828. Formerly it was written as ȣ (Cyrillic uk), italic ⟨u⟩ (Leake 1814), ⟨ü⟩, ⟨ṳ⟩, and ⟨ε⟩.

- ⟨z⟩

Leake first used ⟨z⟩ to represent this sound in 1814. Formerly, it was written variously as a backward 3, Greek zeta (ζ) (Reinhold 1855), ⟨x⟩ (Bashkimi) and a symbol similar to ⟨p⟩ (Altsmar).

- ⟨zh⟩

This sound was variously written as an overlined ζ (Reinhold 1855), ⟨sg⟩ (Rada 1866), ⟨ž⟩, ⟨j⟩ (Dozon 1878), underdotted z, ⟨xh⟩ (Bashkimi), ⟨zc⟩. It was also written with a backward 3 in combination: 3gh and 3c.

Older versions of the alphabet in Greek characters

Arvanites in Greece used the altered Greek alphabet to write in Albanian.[17][18]

| Albanian written in the Greek alphabet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Α | Β | B | Ϳ | Γ | Γ̇ | Γ̇ϳ | Δ | D | Ε | Ε̱ | Ζ | Θ | Ι | Κ | Κϳ | Λ | Λϳ | Μ | Ν | Ν̇ | Νϳ | Ξ | Ο | Π | Ρ | Σ | Σ̇ | Σ̈ | Τ | Υ | Φ | Χ̇ | Χ |

| α | β | b | ϳ | γ | γ̇ | γ̇ϳ | δ | d | ε | ε̱ | ζ | θ | ι | κ | κϳ | λ | λϳ | μ | ν | ν̇ | νϳ | ξ | ο | π | ρ | σ | σ̇ | σ̈ | τ | υ | φ | χ̇ | χ |

| Modern Albanian | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | v | b | j | g | g | gj | dh | d | e | ë | z | th | i | k | q | l | lj | m | n | nj | nj | ks | o | p | r | s | s | sh | t | y | f | h | h |

Older versions of the alphabet in Cyrillic characters

| Modern Latin: | a | b | c | ç | d | dh | e | ë | f | g | gj | h | i | j | k | l | ll | m | n | nj | ng | o | p | q | r | rr | s | sh | t | th | u | v | x | xh | y | z | zh | je | ju | ja | sht |

| Cyrillic: | а | б | ц | ч | д | δ | е | ъ | ф | г | гї, гј, ђ | х | ї, и | ѣ, ј | к | л, љ | л | м | н | њ | нг | о | п | кї, ћ | р | рр | с | ш | т | ѳ | у | в | дс | џ | ју, ӱ | з | ж | ѣе, је | ѣу, ју | ѣа, ја | щ, шт |

| Alternate: | а | б | ц | ч | д | ҙ | е | ә | ф | г | ѓ | х | и | й | к | л | љ | м | н | њ | ң | о | п | ќ | р | р̌ | с | ш | т | ҫ | у | в | ѕ | џ | ү | з | ж | є | ю | я | щ |

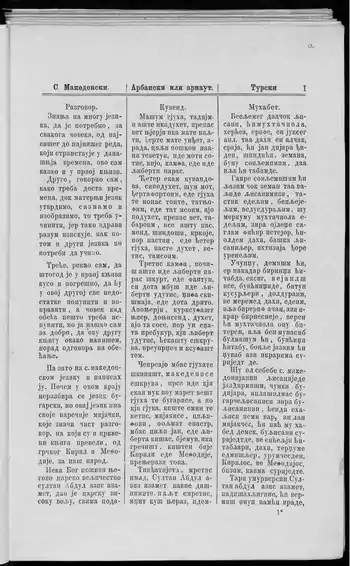

Sample of Albanian language text, written in Cyrillic characters (central column). From the book "Речник од три језика".

Footnotes

- Newmark, Hubbard & Prifti (1982:9–11)

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 111. ISBN 9781400847761.

- Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: a reader of historical texts, 11th-17th centuries. Harrassowitz. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-3-447-04783-8.

- Brian Joseph, Angelo Costanzo, and Jonathan Slocum. "Introduction to Albanian". University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 6 June 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Newmark, Leonard; Philip Hubbard; Peter R. Prifti (1982). Standard Albanian: a reference grammar for students. Andrew Mellon Foundation. ISBN 9780804711296. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- Minaoglou Charalampos, "Anastasios Michael and the Speech about Hellenism", Athens, 2013, p. 37 and note 90 In Greek language.

- Lloshi pp.14-15

- Lloshi p.18

- Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, Birmingham, 15 (1991), p. 20-34.

- Lloshi p. 9.

- H. T. Norris (1993), Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World, University of South Carolina Press, p. 76, ISBN 9780872499775

- Elise, Robert. "The Elbasan Gospel Manuscript (Anonimi i Elbasanit), 1761, and the struggle for an original Albanian alphabet" (PDF). Robert Elise. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-15. Retrieved 2018-03-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-15. Retrieved 2013-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dhimiter Shuteriqi (1976), Shkrimet Shqipe ne Vitet 1332-1850, Tirana: Academy of Sciences of PR of Albania, p. 151, OCLC 252881121

- Straehle, Carolin (1974). International journal of the sociology of language. Mouton. p. 5.

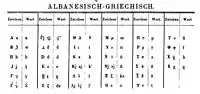

- Albanian-Greek

- Carl Faulmann (1880), Das Buch der Schrift enthaltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller Zeiten und aller Völker des Erdkreises (in German), 1 (2nd ed.), Wien: Druck und Verlag der kaiserlich-königlichen Hof- und Staatsdruckerei

Gallery

Modern Albanian alphabet

Modern Albanian alphabet Albanian "Istanbul alphabet"

Albanian "Istanbul alphabet" Albanian Arabic alphabet

Albanian Arabic alphabet Albanian Greek alphabet

Albanian Greek alphabet

References

- Van Christo, "The Long Struggle for the Albanian Alphabet", formerly available at ; archived at The Long Struggle for the Albanian Alphabet. Christo in turn says "Much of the above material was excerpted or otherwise derived from Stavro Skendi's excellent book The Albanian National Awakening: 1878–1912, Princeton University Press, 1967".

- Robert Elsie, "Albanian Literature in Greek Script: the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth-Century Orthodox Tradition in Albanian Writing", Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 15:20 (1991) .

- Christophoridēs, Kōnstantinos, Psalteri, këthyem mbas ebraishtesë vietërë shqip ndë gegënishte prei Konstantinit Kristoforidit, Constantinople, 1872.

- Trix, Frances. 1997. Alphabet conflict in the Balkans: Albanian and the congress of Monastir. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 128:1-23.

- Macrakis, Stavros M., "Character codes for Greek: Problems and modern solutions" in Macrakis, 1996. Includes discussion of the Greek alphabet used for languages other than Greek. writingsystems.net

- Newmark, Leonard; Hubbard, Philip; Prifti, Peter R. (1982). Standard Albanian: A Reference Grammar for Students. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804711296.

- Lloshi, Xhevat (2008). Rreth Alfabetit te Shqipes. Logos-A. p. 191. ISBN 978-9989-58-268-4.

- Vanja Stanišić (1990), Из историје примене словенске писмености за албански језик (From the History of Using the Slavic Literacy for Albanian Language) (PDF) (in Serbian), 1, Priština: Baština

- Francisco Blanchi, Dictionarium latino-epiroticum una cum nonnullis usitatioribus loquendi formulis, Sac. congr. de propag. fide, Roma, 1635. full text

- Cuneus prophetarum de Christo Salvatore mundi et eius evangelica veritate, italice et epirotice contexta et in duas partes divisa a Petro Bogdano Macedone, sacr. congr. de prop. fide alumno, philosophiae et sacrae theologiae doctore, olim episcopo Scodrensi et administratore. Patavii, 1685 full text

- Francesco Maria da Lecce, Osservazioni grammaticali nella lingua albanese, Stamperia della Sag. cong. di prop. fede, Roma, 1716 full text

- William Martin-Leake, Researches in Greece, London, 1814. full text

- Pun t’ nevoiscem me u dytun per me scelbue scpjrtin, Roma, 1828.

- Joseph Ritter von Xylander, Die Sprache der Albanesen oder Schkiptaren, Andreäischen Buchhandlung, Frankfurt am Main, 1835.

- Johann Georg von Hahn, Albanesischen Studien, Friedrich Mauke, Jena, 1854. full text

- Noctes pelasgicae vel symbolae ad cognoscendas dialectos Graeciae pelasgicas collatae cura Caroli Henrici Theodori Reinhold, classis regiae medici primarii. Athenis, 1855. full text

- Karl Richard Lepsius, Standard Alphabet for reducing unwritten languages and foreign graphic systems to a uniform orthography in European letters, Williams & Norgate, London, W. Hertz, Berlin, 1863. full text

- Demetrio Camarda, Saggio di grammatologia comparata sulla lingua albanese, Successore di Egisto Vignozzi, Livorno, 1864. full text

- Rapsodie d’un poema albanese, raccolte nelle colonie del Napoletano, tradotte da Girolamo de Rada e per cura di lui e di Niccolò Jeno de’ Coronei ordinate e messe in luce. Firenze, 1866.

- T’ verteta t’ paa-sosme kaltsue prei sceitit Alfonso M. de’ Liguori e do divozione e msime tiera kθue n’ fial e n’ ghiù arbnore prei mesctarit scodran. Me sctampen t’ scêitit cuvèn t’ propàgands n’ Rom, 1867.

Cuvendi i arbenit o concilli provintiaalli mbelieδune viettit mije sctat cint e tre ndne schiptarin Clementin XI. pape pretemaδin. E duta sctamp. Conciliun albanum provinciale sive nationale habitum anno MDCCCIII. Clemente XI. pont. max. albano. Editio secunda, posteriorum constitutionum apostolicarum ad Epiri ecclesias spectantium appendice ditata. Romae. Typis s. congregationis de propaganda fide. 1868.

- Franz Miklosich, Albanische Forschungen, Kaiserlich-königlichen Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Wien, 1870 full text

- Konstantin Kristoforidis, Kater unġilat’ e zotit…, Konstantinopol, 1872. text

- Auguste Dozon, Manuel de la langue chkipe ou albanaise, Imprimerie D. Bardin, Paris, 1878. full text

- Louis Benloew, Analyse de la langue albanaise, Maisonneuve et Cie, Paris 1879. full text

- P. W., Grammaire albanaise, Trübner & Co., London, 1887. full text

- Gustav Meyer, Kurzgefasste albanische Grammatik mit Lesestücken und Glossar, Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig, 1888. full text

- Gustav Meyer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch der albanesischen Sprache, Karl J. Trübner, Strassburg, 1891. full text

- Giacomo Jungg, Fialuur i voghel sccȣp e ltinisct, Sckoder 1895. full text [An Albanian–Italian Dictionary]

- Vicenzo Librandi, Grammatica albanesa con la poesie rare di Variboba, Ulrico Hoepli, Milano, 1897. full text

- Georg Pekmezi, Grammatik der albanischen Sprache, Verlag des Albanischen Vereines „Dija“, Wien, 1908. full text

- Skendi, Stavro. 1960. The history of the Albanian alphabet: a case of complex cultural and political development. Südost-Forschungen: Internationale Zeitschrift für Geschichte, Kultur und Landeskunde Südosteuropas 19:263-284,