Alcohol in Afghanistan

The production and consumption of alcoholic beverages, especially wine, in Afghanistan has a long tradition – going back at least to the fourth century BC. Currently, the possession and consumption of alcohol is prohibited for Afghan nationals.[1][2][3] However, the Afghan government provides a license for various many outlets to distribute alcoholic beverages to foreign journalists and tourists, and black market alcohol consumption is prevalent as well.[1][4] Bringing two bottles or two litres of alcoholic beverages is allowed for foreigners entering Afghanistan.[1][3]

The Afghan Royal Family

During the era of King Amanullah and Zahir Shah of the Afghan Royal Family, Alcohol was part of society and the elite in Kabul were known for their extravagant parties.

Overview

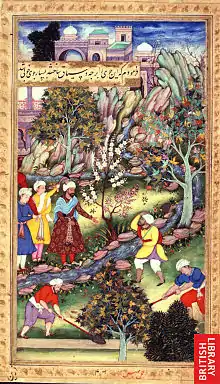

Afghanistan currently has about 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) of areas cultivating grapes and excellent climate and terroir suitable for quality wine.[5] While the history of wine goes back much longer, viticulture seems to have been well established in parts of Afghanistan by at least the fourth century BC.[6] It is said that Babur, the first Mughal emperor, learned about wine in Kabul.[7] His autobiographical memoirs, the Baburnama, is said to mention especially neighboring Istalif (the name possibly derived from Greek staphile, grape), "with vineyards and orchards on either side of its torrent, its waters cold and pure".[7] The Mughal Empire received high quality wine from the Indus valley and Afghanistan.[8] Medieval times saw a comparably flourishing wine production, which was ended in the 18th century.[5] The 1960s saw trials to restart production, which was ended by the Taliban. Around 1969, a French survey estimated that (larger) vineyards covered about 37,500 hectare and 2% of the arable land.[9] The largest part of vineyards was close to Herat, Kandahar and Kabul; smaller areas have been found on the northern border.[9] The French survey has focused on the largest professional vineyards, but mentions grapes being grown in various gardens, even at 2,400 m altitude in Nuristan Province.[9] A 1968 estimate related to a local aid program came to 60,000 hectares (150,000 acres) overall.[10] By comparison, Austrian wine is grown in an area of about 51,000 hectares (130,000 acres).[11] The main current production is around Kabul and goes – for religious reasons – mostly into juice and raisins.

Locals

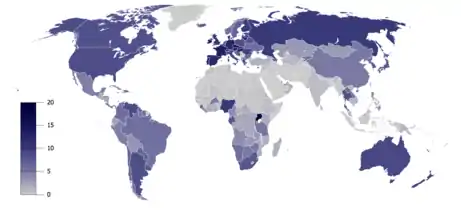

Afghanistan is one of 16 countries in the world where the drinking of alcoholic beverages at any age is illegal for most of its citizens.[2] Violation of the law by locals is subject to punishment in accordance with the Sharia law. Drinkers can be fined, imprisoned or prescribed 60 lashes with whip.[4] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), alcohol consumption in Afghanistan is – officially – almost nonexistent. The total alcohol consumption in Afghanistan was approximately zero during 2003–05; during 2008–10, the recorded alcohol consumption was also zero but unrecorded consumption was estimated at 0.7 liters per capita.[12] Enforcement of the law is inconsistent, and alcohol is widely available on the black market, especially in Kabul and in the western city of Herat, where good homemade wine is reported to be readily available at reasonable prices.[4] In the northern part of the country, alcohol smuggling via Uzbekistan is a large business.[13]

Since the fall of the Taliban, various bars/outlets in Afghanistan had begun to offer alcohol to foreigners and tourists. Kabul has had an active and colorful nightlife, even compared to larger cities in other countries such as New Delhi, Karachi or Tehran. There was a large expatriate community of young and well-paid diplomats, security staff and international aid organizations.[14] In 2010, some of outlets were searched and some Ukrainian waitresses were arrested as prostitutes.[14] There have been several attacks on resorts and bars by Taliban militants.[15][16]

Tourists

Foreign tourists are permitted to import two bottles or two liters of alcoholic beverages when entering Afghanistan.[1][3]

Foreign military troops

Prior to September 2009, the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) headquarters in Afghanistan had at least seven bars that served tax-free beer and wine, including a sport bar named Tora Bora. In 2009, after news of the death of 125 civilians in air strikes, General Stanley McChrystal, the head of ISAF, tried to contact troop officials. After finding that some troops were unable to adequately respond to the incident because they were drunk, he banned alcohol from the US premises.[17] This applies as well to foreign soldiers.[18]

Alcohol was also said to have played a role in the Kandahar massacre, a 2012 incident in which a United States Army Staff Sergeant (Robert Bales) murdered sixteen civilians and wounded six others in the Panjwayi District of Kandahar Province. The US military has since banned alcohol for its troops.[19][20] Despite the ban, US defense officials have sometimes found alcohol at the bases.[19][21]

Soldiers from other countries have been allowed to drink alcohol. Military bases of European troops usually have two liquor stores. German and French troops were allowed two small cans of beer per day in their main base. In smaller camps as in Camp Marmal, the rations were provided on a voucher base and were required to be opened at the spot to avoid the buildup of stocks.[18] After some alcohol-related incidents in 2013, General Jörg Vollmer inspected premises personally to ensure the regulations being followed.[22]

The end of the ISAF in 2015 greatly reduced the number of foreign troops. Compared to ISAF, the current Resolute Support Mission has only a tenth of the forces present in the country. Foreign tourists are allowed to bring two liters of alcohol in a duty-free bag when entering in Afghanistan.[1][23] Drunk driving and the possession of larger amounts of alcohol are subject to jail terms of several months duration.[24] Bundeswehr alcoholic beverages shipments were addressed as well to the enlarged (German) community and invited journalists.[25]

References

- Sean Carberry (6 July 2013). "What A Fella Has To Do To Get A Drink Around The Muslim World". National Public Radio. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- "Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA) in 190 Countries". ProCon.org. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Jilani, Seema (31 August 2010). "Getting drunk in Kabul bars? Pass the sick bag". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- MacKenzie, Jean (30 May 2010). "Last call in Kabul". GlobalPost. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Weinbau in Afghanistan – Die Weinkennerin (Blog entry, confirmed in Wilhelm Hamm, Das Weinbuch: Der Wein, sein Werden und Wesen, 1874)". Der Wein (in German). weinkennerin.de. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Unwin, Tim (12 July 2005). Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade. London New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415144167. ISBN 978-0415144162.

- "Babu, the first Moghul emperor: Wine and tulips in Kabul". The Economist. 16 December 2010. pp. 80–82. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- Anderson, Kym (1 January 2004). The World's Wine Markets: Globalization at Work. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 9781845420765.

- Galet, P. (1969). "Rapport sur la viticulture en Afghanistan" (PDF). Vitis (in French). Ecole Nationale Supérieure Agronomique de Montpellier. 8: 114–128. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Grncarevic, M. (1968). Recommendations for improved handling of grapes and raisins in the Koh-i-Daman valley of Afghanistan – Programme on Agricultural Credit and Cooperatives in Afghanistan (Report). p. 27. 1.

- "Statistic Archive of the AWMB". Austrian Wine. Austrian Wine Marketing Board www.austrianwine.com. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Afghanistan alcohol consumption: Levels and patterns" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2014.

- Clammer, Paul (1 January 2007). Afghanistan. Ediz. Inglese. Footscray, Vic. London: Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781740596428.

- Tandler, Agnes (30 April 2010). "Alkoholversorgung in Afghanistan: Ausländer werden trockengelegt". Die Tageszeitung (in German). Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Ahmad, Aram; Rossenberg, Matthew (18 January 2014). "Deadly Attack at Kabuil Restaurant Hints at Changing Climate for Foreigners". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Taliban attack Kabul resort, citing 'illicit fun' and alcohol". The Christian Science Monitor. 22 June 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- "Alcohol banned on Afghanistan base after troops party too hard". The Telegraph. 8 September 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- "Deutsche Soldaten betrinken sich mit Sanitätsalkohol – Alkoholexzesse in Afghanistan". FOCUS Online (in German). 25 May 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "U.S. Soldiers Find Ways to Get Hands on Alcohol in Afghanistan Despite Ban". Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Troops, Alcohol and War Zones?. "Troops, Alcohol and War Zones? |". Soldier of Fortune Magazine. Sofmag.com. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Despite ban, alcohol reaches U.S. bases in Afghanistan". CTV News. Associated Press. 16 March 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Gebauer, Matthias (25 June 2013). "Afghanistan-Mission: Bundeswehr kämpft gegen Alkoholmissbrauch im Camp". Der Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- "Countries where alcohol is illegal". Fox News. 4 April 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- "Alerts & Warnings". Afghanistan. United States Department of State. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Whitlock, Craig (15 November 2008). "German Supply Lines Flow With Beer in Afghanistan". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 26 November 2015.