Altun Ha

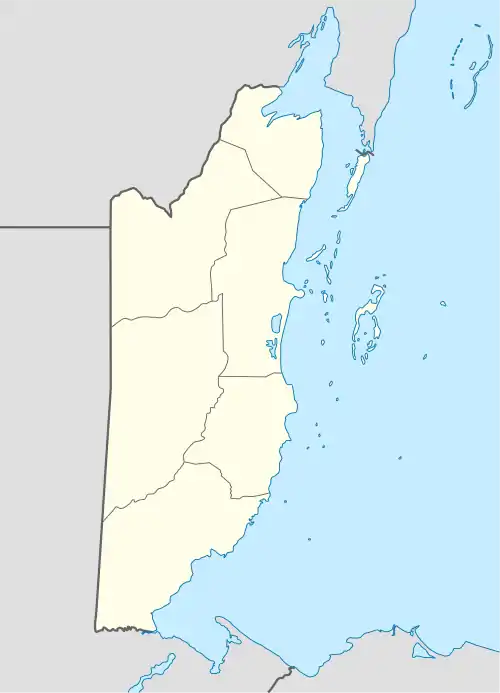

Altun Ha /ɑːlˈtuːn hɑː/[1] is the name given to the ruins of an ancient Mayan city in Belize, located in the Belize District about 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of Belize City and about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) west of the shore of the Caribbean Sea. The site covers an area of about 8 square kilometres (3.1 sq mi).

Temple of the Masonry Altars | |

Shown within Belize | |

| Location | Rockstone Pond, |

|---|---|

| Region | Belize District |

| Coordinates | 17°45′50.22″N 88°20′49.42″W |

| History | |

| Founded | B.C. 900 |

| Cultures | Mayan |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1961 |

Stones from the ruins of the ancient structures were reused for residential construction of the agricultural village of Rockstone Pond in modern times, but the ancient site did not come to the attention of archeologists until 1963. The Old Northern Highway connects Altun Ha to Belize's Northern Highway, and the site is accessible for tourism. The largest of Altun Ha's temple-pyramids, the "Temple of the Masonry Altars", is 16 metres (52 ft) high. A drawing of this structure is the logo of Belize's leading brand of beer, "Belikin".

Etymology

According to the Belize Institute of Archaeology, the site's name means "Rockstone Water," and is a Yucatec Mayan approximation of the name of the nearby village of Rockstone Pond.[2] In Yucatec Mayan, haltun is a stone water deposit or cistern, and ha means water.[3] An ancient emblem glyph for the site has been identified, but its phonetic reading is not currently known.[4]

Archaeological investigations and rediscovery

In 1961, W.R. Bullard conducted excavations led by the Royal Ontario Museum, at Baking Pot and San Estevan, and although no excavations took place, the site was initially called “Rockstone Pond.” In 1963, quarrying activity by local villagers led to the recovery of a large, elaborately carved jade pendant. The current commissioner of archaeology, Hamilton Anderson, notified David M. Pendergast and a reconnaissance trip was made in 1963. Starting in 1964, an archaeological team led by Dr. David Pendergast of the Royal Ontario Museum began extensive excavations and restorations of the site, which continued through 1970. There was a total of 40 months of excavation with a field season in 1971 of ceramic and laboratory analysis.[5]

Setting

Altun Ha lies on the north-central coastal plain of Belize, in a dry tropical zone. The site was very swampy during its pre-Columbian occupation, with very few recognizable water sources. Currently, the only recognizable natural water source is a creek beyond the northern limit of the mapped area. The water sources used during occupation were Gordon Pond, which is the main reservoir, and the Camp Aguada, which is located in the site center. The site may have contained two chultuns, but provenience is lost since they are used in modern times.[5]

The site itself consists of a central precinct composed of Groups A and B. Groups A and B and Zones C, D, and E consist of the nucleated area, with Zones G, J, K, M, N making part of the suburban area. The site does not contain any stela, suggesting that stelae were not part of ceremonial procedures. There are two recorded causeways, one in Zone C and one connecting Zone E and Zone F. The Zone C causeway does not connect to any structures, but is probably related to Structure C13, and was perhaps used for ceremonial purposes. The other causeway connected the two zones where water sources were located, and was constructed for topographical reasons, specifically to traverse areas of swampy land; it may have been impassable without raised walkways.[5]

Occupational history

Altun Ha was occupied for many centuries, from about 900 B.C. to A.D. 1000. Most of the information on Altun Ha comes from the Classic Period from about A.D. 400 to A.D. 900, when the city was at its largest.

Preclassic

The earliest structures found at Altun Ha, found in Zone C, are two round platforms that date to about BC 900−800, structures C13 and C17. Structure C13 contains remnants of postholes and several burials, while C17 has traces of burning, or fire. Structure C13 was an early religious building, with Zone C inhabitants being of relatively high status.[6] The Late Preclassic had a population increase and large public structures were built. The first of these was structure F8 in AD 200. Although this structure was constructed at the end of the Preclassic, the majority of the archaeological evidence dates to the Early Classic. This structure has a two-element stair composed of small steps with stairside outsets that were perhaps devoted to innovation. F8 also had a three-stage development.

Early Classic

One of the most important finds in the Early Classic comes from structure F8, specifically tomb F8/1. The tomb was placed here about fifty years after the construction of the structure. It contained the remains of an adult male who was interred with a jade and shell necklace, a pair of jade earflares, two shell disks, a pair of pearls, five pottery vessels, and fifty-nine valves of Spondylus shells. Bib head beads in the necklace are associated with southern Mesoamerica. The ceramics for the most part reflect the pattern that was being established at other burials in Altun Ha. Above the burial, however, the roof showed association to the large Mexican site Teotihuacan. The burial was capped with over 8,000 pieces of chert debitage and 163 formal chert tools. The ritual offering, or cache, also contained jade beads, Spondylus valves, puma and dog teeth, slate laminae, and a large variety of shell artifacts. The clear association to Teotihuacan however, comes from the 248 Pachuca green obsidian objects and the 23 ceramic jars, bowls and dishes.[7] The obsidian is of the Miccaotli or Early Tlamimilolpa phase, suggesting that this symbolism was still important and dominant at Teotihuacan. This offering may be of importance to Teotihuacan because of the associations that the ruler in the burial had with central Mexico or the association that the entire Altun Ha community had with Teotihuacan.[8]

There is also evidence of contact and trading with the other side of Mesoamerica in the intermediate area. An offering in the central ceremonial precinct contained an undecorated lidded limestone vessel with jadeite objects, two pearls, laminae of crystalline hematite, Spondylus shell beads, and a tumbaga gold-copper alloy bead representing a jaguar claw. This deposit has been dated to about 500. Traditionally, it was not believed that the Maya had gold during the Classic period; gold was restricted to the Postclassic. This is in part because many believed that gold was not naturally occurring in the Maya area, but recent investigations have shown that placer gold can be found in the streams of the upland zone of western Belize. The Maya most likely did not use metallurgy because of a lack of techniques, which may have been due to the fact that yellow in Maya ideology represent dying plant life and crop failure. This artifact is also identical with other artifacts of the Cocle in central Panama. The Cocle had a sufficient amount of metalworking by 500, and surely played a role in trade relationships beyond Panama. This discovery also shows that important trade networks were set up much earlier than previously thought.[9]

Late Classic

In general, the elite burials at Altun Ha during the Late Classic can be characterized by large amounts of jade. Over 800 pieces of jade have been recovered at the site. More than 60 of these pieces are carved. The beginning of the Late Classic at Altun Ha had one of the most interesting burials in the Maya lowlands. Structure B-4 has tombs with many jade artifacts, including a large jade plaque with a series of twenty glyphs in the phase six construction level. In the 1968 field season, after excavating many tombs in Structure B-4, also called the Temple of the Masonry Altars, the seventh phase of construction revealed the most elaborate tomb at the site nicknamed “The Sun God’s Tomb”.

The Sun God's Tomb

The Sun God's Tomb is in Structure B-4, also called the Temple of the Masonry Altars. Structure B-4 is in Group B, which is part of the central precinct at Altun Ha, and has a height of 16 meters. Phase VII, the level where this tomb is, is dated to about 600−650, which is at the beginning of the Late Classic period. The tomb is the seventh and earliest in B-4, which made the excavators designate this burial Tomb B-4/7.[10]

Tomb B-4/7 contained the skeleton of an adult male with many offerings. The body was fully extended dorsally with the skull facing south-southwest. The person had a height of 170–171 cm, with the recovered skeletal materials consisting of a fragment of the skull, the mandible, long bones, five teeth, two vertebrae, five carpal bones, the patellas, and miscellaneous metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges.[10]

The bulk of the interpretations, research, and interest in this tomb have undoubtedly been on the artifacts that were contained in this particular burial. In the initial study, Pendergast classifies these artifacts between perishables and non-perishables.

The perishable artifacts that are in the burial that the researchers were able to recognize include a wooden platform that the body was placed on, felid skins, cloth, matting, cordage, rods, stuccoed objects, red pigment, and gray clay. Not all perishable objects have been interpreted for their original use in the burial, but some have clear associations. The entire tomb was covered in cloth, with textile impressions noted on the pottery. Red pigment was distributed throughout, with evidence of it on most of the jade.

The researchers documented 43 non-perishable artifacts. These include ceramic bowls; shell beads; jadeite anklets, bracelets and beads; pearls; pyrite and hematite artifacts; and, the most outstanding of all, a carved jade head of the Sun God, Kinich Ahau. The head has a height of 14.9 cm, a circumference of 45.9 cm and a weight of 4.42 kg. It was placed at the pelvis of the body, with the face of the jade boulder facing the skull.[10]

The Sun God's Tomb marks the starting point for tomb construction in Structure B-4 during the Late Classic period. The unusual form of this tomb shows the distinctive cultural aspects of Altun Ha and the Caribbean zone compared to the inland Classic Maya sites. Pendergast suggests that with so much jade found at the site, the jade head may have been carved at the site with imported jade. The giant jade head also suggests that this small site had a strong status as a trade or ceremonial center. Pendergast suggests that this tomb contained a priest that was associated with the Sun God and that Structure B-4 was dedicated to this deity, based on this one artifact.

More recent research, however, has shown that this interpretation may be incorrect: it suggests that this giant jade head is a Jester God. When drawing this figure spread out on a plane, the figure on this carving shows more of a resemblance to a bird deity with maize iconography, not Kinich Ahau.[11] The Jester God is an early symbol of Maya rulership and is usually seen iconographically in the head, or in this case the jade head.

With so many artifacts associated with this tomb, it is clear that the male buried in here was of great importance.[12] The Jester God argument is a better fit for what this person represented, which would also correlate with this being the first tomb constructed in Structure B-4.

Terminal Classic

By 700, modifications in the Central Precinct became rarer, and in Plaza B only Structures B4 and B6 were modified regularly, while Plaza A was still being modified extensively. By 850, structures B5 and A8 were completely abandoned. Gradual abandonment of the site began in 800, except for Zone E, which actually reached its peak usage and occupation between 700 and 800.[13]

Structure D2 is located at the edge of the site's Central Precinct and is dated to the Late-Terminal Classic. This structure in particular yielded a stemmed bifacial blade of Pachuca green obsidian in a post-abandonment offering. The form, size and manufacturing characteristics are very similar to those found in F8. Two possible explanations for the context of this artifact are that the blade could have been produced long after the decline of Teotihuacan, or was reused from an earlier time period.

Postclassic

In the Postclassic, Structures A1 and A5 were solely used for depositing the dead. By the beginning of the eleventh century, the site of Altun Ha was completely abandoned. During the Late Postclassic after 1225, however, there was a renewed limited occupation at Altun Ha which lasted probably until the fifteenth century. Lamanai-related Postclassic ceremonial vessels were excavated atop B-4.[5]

Diet at Altun Ha

The diet at Altun Ha was a maize based (C-4) diet, but there was also a large marine component to their diet compared to other sites in the Maya area. The marine/reef resources were more important here than in other regions. Between the Preclassic and Early Classic, there was a dramatic increase of maize consumption, which researchers argue is an indication of a rise in intensive maize agriculture at the beginning of the Early Classic. The individuals with the highest recognized status during this time period also had the highest intake of maize. In the Late Classic, more maize was consumed in the central precinct than in the outer zones, and Zone C had a higher degree of reef resources than in other areas. In the Postclassic, a higher portion of terrestrial animals were consumed, possibly deer or dogs.[14]

Caches at Altun Ha

Caches occur in two categories at Altun Ha. The largest class is in communally built structures that were dedicated to public ritual, the second occurs in residential structures with usually a single-family focus. The primary axis was the principal determinant of cache position in communally built structures. The primary axis functioned as the main avenue of communication with deities. In other public and domestic contexts, there are offerings that are away from the primary axis, and this is based on a matter of exclusion. Late Preclassic caches at Altun Ha can be defined by the round platform. Jade objects become significant in offerings by 450−300 BC. Classic Period caching practices at Altun Ha consisted of single, highly varied offerings in context with structural modification. The caches during this time period had a high scale of ceremonial value and made a forceful statement of the site's prominence.[15]

See also

References

- Indira Craig (host) (April 17, 2013). "News broadcast". 7 News Belize. Event occurs at 45:23. Tropical Vision Limited. Channel 7. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- Belize. National Institute of Culture and History, Institute of Archaeology. "Archaeology of Altun Ha". Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Bolles, David (2001). "Combined Dictionary–Concordance of the Yucatecan Mayan Language". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI). Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- Bíró, Péter (2012). "Politics in the Western Maya Region (II): Emblem Glyphs". Estudios de Cultura Maya. Mexico, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas. XXXIX: 57. ISSN 0185-2574. OCLC 1568280.

- Pendergast, David M.1979 Excavations at Altun Ha, Belize, 1964-1970, Volume 1. Royal Ontario Museum.

- Pendergast, David M.1982 Excavations at Altun Ha, Belize, 1964-1970, Volume 2. Royal Ontario Museum.

- Pendergast, David M. 1971 Evidence of Early Teotihucan-Lowland Maya Contact at Altun Ha. American Antiquity 36(4):pp. 455-460.

- Pendergast, David M. 2003 Teotihuacan at Altun Ha: Did It Make a Difference? in The Maya and Teotihuacan : reinterpreting early classic interaction, edited by Geoffrey E. Braswell, 1st ed. pp 235-247 University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Pendergast, D. M. 1970 Tumbaga Object from the Early Classic Period, Found at Altun Ha, British Honduras (Belize). Science 168(3927):pp. 116-118.

- Pendergast, David M. 1969 Altun Ha, British Honduras (Belize): the Sun God's tomb [by] David M. Pendergast. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

- Taube, Karl 1998 The Jade Hearth: Centrality, Rulership, and the Classic Maya Temple. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D. Houston, pp. 427-478. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C.

- Fields, Virginia M. 1991 The Iconographic Heritage of the Maya Jester God. In Sixth Palenque Round Table, 1986, edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Virginia M. Fields. Electronic version. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Yermakhanova, Olga A., 2005 Kingship, Structures and Access Patterns on the Royal Plaza at the Ancient Maya City of Altun Ha, Belize: The Construction of a Maya GIS. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Department of Geography and Anthropology, Louisiana State University.

- White, Christine D., David M. Pendergast, Fred J. Longstaffe, and Kimberley R. Law 2001 Social Complexity and Food Systems at Altun Ha, Belize: The Isotopic Evidence. Latin American Antiquity 12(4):pp. 371-393.

- Pendergast, David M., Intercession with the Gods: Caches and Their Significance at Altun Ha and Lamanai, Belize 1998 in The sowing and the dawning : termination, dedication, and transformation in the archaeological and ethnographic record of Mesoamerica, edited by Shirley Boteler Mock, 1st ed. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Altun Ha. |

Media related to Altun Ha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Altun Ha at Wikimedia Commons- Altun Ha on BelizeDistrict.com