Piedras Negras (Maya site)

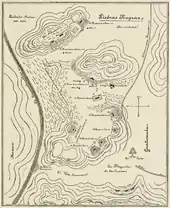

Piedras Negras is the modern name for a ruined city of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization located on the north bank of the Usumacinta River in the Petén department of northeastern Guatemala. Piedras Negras is one of the most powerful of the Usumacinta ancient Maya urban centers.[1] Occupation at Piedras Negras is known from the Late Preclassic period onward, based on dates retrieved from epigraphic information found on multiple stelae and altars at the site.[2] Piedras Negras is an archaeological site known for its large sculptural output when compared to other ancient Maya sites.[1] The wealth of sculpture, in conjunction with the precise chronological information associated with the lives of elites of Piedras Negras, has allowed archaeologists to reconstruct the political history of the Piedras Negras polity and its geopolitical footprint.[2]

Location

Southern Lowlands, Modern-Day: Guatemala

Geography

Piedras Negras is located along the eastern banks of the Usumacinta River.[2] The settlement is oriented around plazas, without a grid system.[2] The polity is built into a series of hills, offering a natural defensive structure, and is currently heavily forested.

Etymology

The name Piedras Negras means "black stones" in Spanish. Its name in the language of the Classic Maya has been read in Maya inscriptions as Yo'k'ib' ([ˈjoʔkʼib]), meaning "great gateway" or "entrance",[3] considered a possible reference to a large and now dry sinkhole nearby.[4] It may also be a reference to its location as a prominent intermediary along the trade routes leading to the Tabasco floodplain.[1] Some authors think that the name is Paw Stone, but is more likely to be the name of the founder as hieroglyphs on Throne 1 and altar 4 show.

History of Piedras Negras

Piedras Negras had been populated since the 7th century BC. Its population seems to have peaked twice. The first population peak happened in the Late Preclassic period, around 200 BC, and was followed by a decline.[5] The second population peak of Piedras Negras happened in the Late Classic period, around the second half of the 8th century, during which the maximum population of the principal settlement is estimated to have been around 2,600. At the same time, Piedras Negras was also the largest polity in this region with a total population estimated to be around 50,000.[2]

Piedras Negras was an independent city-state for most of the Early and Late Classic periods, although it was sometimes in alliance with other states of the region and may have paid tribute to others at times. It had an alliance with Yaxchilan, in what is now Chiapas, Mexico, some 40 km up the Usumacinta River. Ceramics show the site was occupied from the mid-7th century BC to 850 AD. Its most impressive period of sculpture and architecture dated from about 608 through 810, although there is some evidence that Piedras Negras was already a city of some importance since 400 AD.

Panel 12 of Piedras Negras shows three neighboring rulers as captives of Ruler C. One of the captives might be the ninth king of Yaxchilan, Joy B'alam (also known as Knot-Eye Jaguar I), who continued to reign after the panel was made. As subservient rulers were often depicted as bound captives even while continuing to rule their own kingdoms, the panel suggests that Piedras Negras may have established its authority over the middle Usumacinta drainage in about 9.4.0.0.0 (514 AD).[6][7]

The artistry of the sculpture of the Late Classic period of Piedras Negras is considered particularly fine. The site has two ball courts and several plazas; there are vaulted palaces and temple pyramids, including one that is connected to one of the many caves in the site. Along the banks of the river is a large boulder with the emblem glyph of Yo’ki’b carved on it, facing skyward.

A unique feature of the monuments at Piedras Negras is the frequent occurrence of the so-called "artists' signatures". Individual artists have been identified by the use of recurring glyphs on stelae and other reliefs.

Ruler 7 (reigned 781-808?) of Piedras Negras was captured by K'inich Tatbu Skull IV of Yaxchilan. This event was recorded on the lintel 10 of Yaxchilan.[8] Piedras Negras might have been abandoned within several years after this event.[9]

Before the site was abandoned, some monuments were deliberately damaged, including images and glyphs of rulers defaced, while other were left intact, suggesting a revolt or conquest by people literate in Maya writing.

Late Preclassic/Early Classic Rulers

Relatively little is known of the Late Preclassic/Early Classic rulers, but excavations of the West Group Plaza found masonry dating to the Early Classic, and altar 1 is dedicated to Ruler A, dating to AD 297.

K'an Ahk I:[10] AD 297- ?, induction Long Count Date: 8.13.0.0.0[1]

K'an Ahk II:[10] AD ca 460-ca 478

Yat Ahk I (or Turtle Tooth): 510-514.[1] Panel 2 mentions him, and states that Turtle Tooth had an overlord at an unknown cite.[11] Ancient Maya name unknown, but some scholars believe his name to be Yah Ahk 1[12]

Ruler C: 514-53, induction Long Count Date: 9.4.0.0.0.[1] Lintel 12 depicts Ruler C receiving 4 captives, including Knot-eye Jaguar of Yaxchilan.[1] Stela 30, long count 9.5.0.0.0 (AD 534), is possibly a celebration of a k'atun ending.[1] Stela 29, long count 9.5.5.0.0 (AD 539), is in celebration of a hotun (a five-year period)ending during Ruler C's reign.[1] Both would have been causes of celebration in antiquity.

Late Classic Rulers

K’inich Yo’nal Ahk I: 603-639, induction long count: 9.8.10.6.16.[1] K’inich Yo’nal Ahk I ran a series of military conquests throughout the Usumacinta area, and defeated Palenque in AD 628, taking captive Ch’ok Balum, one of Palenque's lords.[2] Stela 25 commemorates his accession.[1] After K’inich Yo’nal Ahk I's accession, he razed the Early Classic monuments and some of the buildings, in an effort to discredit the symbols of earlier kings, and, additionally, began construction and renovating older architecture in the South Group to establish his dynasty and lineage.[1]

Dedications:[1]

Stelae: 25, 26, 31

Itzam K'an Ahk I: 639-686, induction Long Count: 9.10.6.5.9.[1] The son of K’inich Yo’nal Ahk I, Ruler 2 continued his father's military conquests, and in 662, was victorious over Santa Elena, which is commemorated in Stela 35.[1] Panel 15 celebrates the capture of an unknown polity and an unknown captive, which was issued by Ruler 2's son after his death.[11] This act of commissioning an artist to memorial one's predecessor is not rare and can be seen again in Ruler 2's commission of Panel 2 which celebrates the k’atun anniversary of the death of K’inich Yo’nal Ahk I. It also recalls Turtle Tooth's receiving of 6 captives after battle and mentions his unknown overlord at another site. Later in his reign two stelae were placed in the West Group, whereas early stelae were raised in South Group.[1]

Dedications:[1]

Panels: 2, 4, 7

Stelae: 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39

Throne: 2

K’inich Yo’nal Ahk II: 687-729, ascension long count: 9.12.14.13.1.[1] All eight of his stelae, placed in West Group, indicating that K’inich Yo’nal Ahk II abandoned the South Group which had been used by his ancestor's.[1] The son of Ruler 2, K’inich Yo’nal Ahk II is most known for his marriage alliance and military defense. He married Lady K’atun Ajaw from Namaan in AD 686.[1] While the site of Namaan is currently unidentified, this marriage shows that Piedras Negras and Namaan were important to one other, and both would have benefited from the marriage. While Ahk II suffered a few military losses, notably the loss of La Mar and in 725 the capture of one of his sajal (a lesser lord) by Palenque, the ruler was victorious over Yaxchilan in 727, capturing a sajal, as commemorated in Stela 8.[1] K’inich Yo’nal Ahk II's tomb has been identified as Burial 5, under Patio 1 in front of J-3.[1]

Dedications:[1]

Altar 1

Panel: 15

Stelae: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Itzam K'an Ahk II: 729-757, induction long count: 9.14.18.3.13.[1] Ascension Stela: Stela 11. Son of K’inich Yo’nal Ahk II. Most of his stelae were in West Group. Using Panel 3, issued by Ruler 7, was placed in front of O-13, in the East Group. Excavated in 1997 by Héctor Escobedo and Tomás Barrientos, a royal interment, Burial 13, was found.[1] The interment was similar to that of Burial 5, with the exception that it had been reentered later, indicated by absent or burned bones. Tomb reentry was culturally significant to the Maya, and indicates that Ruler 4 was well respected both in life and in death.[2]

Dedications:[1]

Altar: 2

Stelae: 9, 10, 11, 22, 40

Yo’nal Ahk III: 758-767, induction long count: 9.16.6.17.1.[1] Son of Ruler 4, ascension stela: Stela 14. Stelae were placed in the East Group, indicating a move from the South and West Groups previously used by rulers.[2]

Dedications:[1]

Stelae: 14, 16

Ha’ K’in Xook: 767-780, induction long count: 9.16.16.0.4.[1] Accession stela: Stela 23. Brother of Yo’nal Ahk III, son of Ruler 4, abdicated in 780, according to Throne 1.[11]

Dedications:[1]

Stelae: 13, 18, 23

K'inich Yat Ahk II: 781-808, induction long count: 9.17.10.9.4.[1] Son of Ruler 4, brother of Yo’nal Ahk III and Ha’ K’in Xook, ruler 7 continued to use the East Group, specifically O-13, as the area for his stelae to be placed.[1] In 785, he commissioned Throne 1, placing it in str. J-6, one of the finest pieces of sculpture from Piedras Negras.[1] Ruler 7 engaged in numerous military conquests, including the defeat of Santa Elena in 787 and wars with Pomoná. Stela 12 depicts Ruler 7 with La Mar Ajaw, Parrot Chaak, sitting in judgement over captives from Pomoná, indicting a close military allegiance between the two.[1] Ruler 7's campaigns ended in 808 when he was captured by K’inich Tatb’u Skull III, ruler of Yaxchilan, depicted in Lintel 10.[11]

Dedications:[1]

Altar 4

Stelae: 12, 15

Panel: 3

Throne: 1

Decline of Piedras Negras

Ruler 7 is the last known of king of Piedras Negras. With his capture, the dynasty which had governed over Piedras Negras since AD 603 effectively ended. However, even before his capture, the polity seemed to be in decline. When Throne 1 was unearthed in 1930, it had been shattered. After additional excavations in the 1990s, it became evident that there were other signs of burning and destruction throughout the site, but most notably at the royal palace. The internal feuding between Piedras Negras and Yaxchilán, beginning in the fifth century AD, played a large role in the instability of the polity. The conflict between the two was not limited to fighting and warfare; the two polities both are known for their artistic output which offered an additional way in which to validate and enforce the polity's respective power. Though monument construction and dedication did not continue into the ninth century, occupation of the site itself did. The site was abandoned by AD 930.[13] It is not possible to fully ascertain whether limited occupation continued as no archaeological evidence has yet been unearthed for occupation continuing after AD 930.

Glyphs

Using the abundant number of stelae recovered from Piedras Negras, Tatiana Proskouriakoff revolutionized current understanding of Maya hieroglyphs. Proskouriakoff realized that stelae which depicted a person within a niche and the glyphic texts on them were in fact the long count recounting important events in the life of a ruler, such as their date of birth and accession to the throne.[1] Proskouriakoff's contribution to Mayan epigraphy changed the idea of the ancient Maya from a people of peace and cosmology to a people actively participating and recording political and social histories.

List of rulers

| Name | Glyph | Reigned from | Reigned until | Monuments | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K'an Ahk I |  |

c. 297 AD[14] | Ruler A was later captured by Moon Skull of Yaxchilan[14] | ||

| K'an Ahk II |  |

c. 478 AD[14] | |||

| Yat Ahk I |  |

c. 510 AD[15] | |||

| Ruler C | June 30, 514 AD[14] | c. 520 AD[15] |

|

||

| K'inich Yo'nal Ahk I |  |

November 14, 603 AD[16] | February 3, 639 AD[16] | Some scholars have argued that K'inich Yo'nal Ahk I refounded the ruling dynasty at Piedras Negras.[1] | |

| Itzam K'an Ahk I |  |

April 12, 639 AD[17] | November 15, 686 AD[17] | ||

| K'inich Yo'nal Ahk II |  |

January 2, 687 AD[19] | c. 729 AD[17][20] | ||

| Itzam K'an Ahk II |  |

November 9, 729 AD[21] | November 26, 757 AD[21] | There is evidence that Itzam K'an Ahk II started a new patriline at Piedras Negras.[22] | |

| Yo'nal Ahk III |  |

March 10, 758 AD[23] | c. 767 AD[23] | ||

| Ha' K'in Xook |  |

February 14, 767 AD[23] | March 24, 780 AD[23] | Appears to have either died or abdicated.[23] Scholars are unsure if March 24, 780 AD refers to Ha' K'in Xook's death date, or rather the date of his burial.[1][23] | |

| K'inich Yat Ahk II |  |

May 31, 781 AD[24] | c. 808 AD[25] | Took the throne almost a year following the death of Ha' K'in Xook. Despite this time gap, there is no evidence anyone was ruling Piedras Negras in the interim.[26] He was later captured by K'inich Tatbu Skull IV of Yaxchilan.[27] | |

Modern history of the site

The site was first explored, mapped, and its monuments photographed by Teoberto Maler at the end of the 19th century.

An archeological project at Piedras Negras was conducted by the University of Pennsylvania from 1931 to 1939 under the direction of J. Alden Mason and Linton Satterthwaite. Further archaeological work here was conducted from 1997 to 2000, directed by Stephen Houston of Brigham Young University and Hector Escobedo of the Universidad del Valle de Guatemala, with permission from the Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala (IDAEH).

Mayanist Tatiana Proskouriakoff was the first to decipher the names and dates of a Maya dynasty from her work with the monuments at this site, a breakthrough in the decipherment of the Maya Script. Prouskourikoff was buried here in Group F after her death in 1985.

In 2002 the World Monuments Fund earmarked 100,000 United States dollars for the conservation of Piedras Negras. It is today part of Guatemala's Sierra del Lacandón national park.

References

- Sharer, Robert; Traxler, Loa (2006). The Ancient Maya. California: Stanford University Press. pp. 421–431.

- Zachary Nathan Nelson. "SETTLEMENT AND POPULATION AT PIEDRAS NEGRAS, GUATEMALA" (PDF). famsi.org. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Martin, Simon & Grube, Nikolai (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 139. ISBN 0-500-05103-8.

- Ibid. Sinkholes and caves such as this are frequently associated in Maya mythology with entrances to the Underworld or Xibalba.

- Johnson, Kristopher (2004). "The Application of Pedology, Stable Carbon Isotope Analyses and Geographic Information Systems to Ancient Soil Resource Investigations at Piedras Negras, Guatemala". Scholarsarchive.byu.edu. Brigham Young University. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "The Captives on Piedras Negras, Panel 12". Decipherment.wordpress.com. 18 August 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "DIGITAL CAHULEU: Andrews Collection, Patten Rubbing". Whp.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- "Mesoweb Encyclopedia". Mesoweb.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- O'Neil, Megan (2014). Engaging Ancient Maya Sculpture at Piedras Negras, Guatemala. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780806188362.

- Pitts, Mark. A Brief History of Piedras Negras—As Told by the Ancient Maya. 2011

- O'Neil, Megan. Engaging Ancient Maya Sculpture at Piedras Negras, Guatemala. University of Oklahoma Press, 2014

- Gyles, Iannone; et al. (2016). Ritual, Violence, and the Fall of the Classic Maya Kings. Florida: University Press of Florida. pp. 108–134.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 140.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 141.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 142.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 143.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 145.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 147.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 148.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 150.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 151.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 152.

- Martin & Grube 2000, p. 149.

- O'Neil 2014, p. 142.

- Martin & Grube 2000, pp. 152–153.

Bibliography

- Martin, Simon; Grube, Nikolai (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500051030.

- "Piedras Negras, Guatemala". 2003 Nominations. Global Heritage Fund. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- Förstemann, Ernst (1902). "Eine historische Maya-Inschrift". Globus. 81 (10): 150–153. ISSN 0935-0535.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Piedras Negras, Maya site. |