Apple maggot

The apple maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella), also known as the railroad worm (but distinct from the Phrixothrix beetle larva, also called railroad worm), is a species of fruit fly, and a pest of several types of fruits, mainly apples. This species evolved about 150 years ago through a sympatric shift from the native host hawthorn to the domesticated apple species Malus domestica in the northeastern United States. This fly is believed to have been accidentally spread to the western United States from the endemic eastern United States region through contaminated apples at multiple points throughout the 20th century. The apple maggot uses Batesian mimicry as a method of defense, with coloration resembling that of the forelegs and pedipalps of a jumping spider (family Salticidae).

| Apple maggot | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Tephritidae |

| Subfamily: | Trypetinae |

| Tribe: | Carpomyiini |

| Subtribe: | Carpomyina |

| Genus: | Rhagoletis |

| Species: | R. pomonella |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhagoletis pomonella (Walsh, 1867) | |

| Synonyms | |

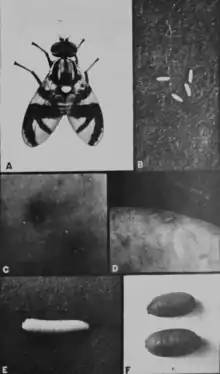

The adult form of this insect is about 5 mm (0.20 in) long, slightly smaller than a housefly. The larva, which is the stage of this insect's lifecycle that causes the actual damage to the fruit, is similar to a typical fly larva or maggot. Caterpillars, especially the larvae of the codling moth, that infest the insides of apples are often confused with the apple maggot. However, these organisms generally feed in the apple's core while apple maggots feed on the fruit flesh. The apple maggot larvae are often difficult to detect in infested fruit due to their pale, cream color and small body size. The adult fly lays its eggs inside the fruit. Larvae consume the fruit and cause it to bruise, decay, and finally drop before ripening. The insect overwinters as a pupa in the soil. It only emerges after metamorphosis into a relatively defenseless fly. Adults emerge from late June through September, with their peak flight times occurring in August.

Description

Eggs are fusiform and pearly white when laid in fruit, but after a short period of time in the fruit, they turn a cream color. Developing larvae can be clearly seen within the translucent eggs.[1]

The larva is white or cream-colored, but if it eats green pulp near the fruit skin, the green shows through the skin. Larvae range in length from 7 to 8.5 mm and in width from 1.75 to 2 mm.[1]

The pupa is formed inside the larval skin, after the maggot shortens and becomes inactive. During the pupal stage, the larva is initially light yellow, but turns yellow-brown within hours and darkens progressively. The pupae range in length from 4 to 5 mm and in width from 2 to 2.5 mm and are an elongated oval shape.[1]

Adult female R. pomonella are shiny black with white markings and an average length of 6.25 mm. Their wingspan averages 12 mm. They have green eyes and a white stripe on each side of the thorax. The abdomen is shiny black with four uniform white bands. When the ovipositor is not in use, it is retracted completely into the abdomen. The ovipositor is horn-like, hard, and chitinous. Male R. pomonella have a similar appearance to the females but are smaller with an average length of 4–5 mm; the size of the abdomen is the main difference, with only five of the seven segments visible (the sixth and seventh are retracted under the fifth). The sixth and seventh segments contain a chitinous framework that support a long, spiraling (when coiled) chitinous penis, which is terminated by a spiral brush with numerous stiff hairs.[1]

Distribution and habitat

R. pomonella is prevalent in North America, though endemic only to the eastern United States. The range of the apple race is contained within that of the hawthorn race, including the northeastern and midwestern US as well as eastern Canada.[1] The species has been found as far south as Florida. In 1979, the apple maggot was reported to be found for the first time on a backyard tree in Portland, Oregon.[2] California quarantine inspection records show apple maggot infest fruit have been intercepted at border patrol stations since around 1950. A misidentified apple maggot, originally thought to be the snowberry maggot Rhagoletis zephyria Snow, was found in the Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA) tephritid fly collection, and the fly was collected in 1951 in Rowena, Oregon.[3] The ODA conducted a survey in 1980 to measure the distribution of the apple maggot, and traps in southwestern Washington showed apple maggot distribution in and around Vancouver, Washington, a suburb of Portland, Oregon.[2] The apple maggot has spread to the Northwest, including Washington, Oregon, and northern California. They are believed to have been spread through contaminated apples, most likely to have been accidentally introduced to the western United States multiple times over the past few decades.[3][4] This theory is supported by lack of R. pomonella infestation on C. douglasii in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, implying that the fly in these regions is not native on hawthorn. There are recorded sightings of R. pomonella from Southern Utah and New Mexico, as well as in the Sierra Madre Oriental Mountains and the Altiplano central highlands of Mexico.[4]

The original ancestral host of the apple maggot was the wild hawthorn (Crataegus spp.), but in the mid-1800s when the apple (Malus spp.) was introduced to North America, R. pomonella, able to take advantage of the new host, evolved.[5] Peach, pear, cherry, plum, chokeberry, cranberry, dogwood, and fruits of the Japanese roses Rosa rugosa and Rosa carolina can also host apple maggots.[6][7] However, apple maggots are not usually a serious pest of plums, cherries, and pears; larvae have been found in pears but not adult flies.[7]

Life history

Flies emerge in the summer beginning in June and continuing through August and September, and eggs are laid in the apple fruit.[8] The fly cycles through one generation a year with adults living up to four weeks.[6][9] In Oregon and Washington, apple maggots have been found to emerge in early July with peak times in late August or early September. Flies have been found as late as November, and larvae have been found in late December.[3]

Females deposit eggs one by one via ovipositor in the skin of the fruit. Punctures are difficult to see with the naked eye at first but are visible once the wound darkens. A female can produce 300 to 400 eggs in her lifetime, and eggs develop in succession and are deposited as soon as they mature. Studies show that eggs develop faster at warmer temperatures that they do at cooler temperatures. When the weather is exceptionally warm, eggs may develop just two weeks after emergence. Eggs hatch within two to six days, and larvae feed on the fruit ranging from two weeks to more than two months, depending on temperature and on the hardness of the fruit. Young larvae are difficult to see because they are the same white color as the pulp. Larvae spend the pupal stage in the soil at a depth of one to two inches in the ground or sometimes in decayed fruit. Early-emerging larvae may only spend a month in the pupal stage, but late-emerging larvae remain dormant throughout the winter.[8]

Feeding behavior

Haws and crab-apples are the original food source of the flies, but they have moved to feeding on mainly apples, though they have been found feeding on other cultivated fruits. Male and female flies feed constantly from the surface of their food source, primarily apples. The fly extends its proboscis and drops saliva onto the skin of the apple, and the saliva is used as a solvent for substances on the apple. If drier substances are present, the fly dissolves them before sucking up fluid. Larvae use chitinous hooks to cut through pulp just below the skin of the fruit, producing characteristic brown markings, leading to the larvae being called "railroad worms". If the apples are still growing, larvae burrows are difficult to find because they heal quickly. Softened apples allow larvae to grow rapidly and break down pulp, even to the point of feeding at the core.[8]

Mating

R. pomonella adult flies may begin copulation as early as eight days old.[8] Males attempt copulation when females are in oviposition on fruit.[9] The male springs onto the female and positions his forefeet on her abdomen and his second pair of feet on her wings. The male waits and uncoils his spring-like penis, quickly entering the opening of the ovipositor when the female extends it. Mating occurs on the host plant and averages thirty minutes, during which the flies are attached and can fly about. Then, when the flies separate, the ovipositor and penis are quickly retracted.[8]

The flies undergo multiple matings, which benefits both sexes. Generally, multiple mating is thought to be a more adaptive strategy for males because of male potential to fertilize many females and the trend of greater female parental investment. However, studies have shown increased female fecundity and fertility from multiple matings.[9] Females have long-term sperm storage, and there is little to no parental investment after she lays eggs. A 2000 study by Opp and Prokopy found that male and female apple maggot flies mated up to six times a day in males and eight times in females, thus there is most likely no mating refractory period, unlike other tephritid species like Mediterranean fruit flies, whose females may mate only after stored sperm is depleted.[9]

Threats

Predators

The apple maggot is not as heavily targeted by predators and parasites as other insects because for most of its lifespan it is inaccessible, living inside apples as larvae and in soil as pupae. Occasionally flies are captured by various species of spiders, such as the Dendryphantes militaris Hentz, which predates on flies in apple trees. Birds may feed on larvae, pupae, or adults. Some full-grown maggots leaving the apples are taken by ants.[10] The maggot stage has other predators including several braconid wasps: Utetes canaliculatus, Diachasmimorpha mellea, and Diachasma alloeum.[11]

Egg parasite

A 1920 study showed that apple maggot eggs were parasitized by Anaphoidea conotrecheli Girault, which is a common egg parasite of plum curculio and grape curculio. The study states that the abundance of Anaphoidea conotrecheli parasitization of apple maggot eggs would depend on the abundance of the eggs of its principal host, the plum curculio.[10]

Larval parasite

Opius mellus Gahan (Biosteres rhagoletis Richmond) was bred from puparia of apple maggots in Maine in 1914 and was also found in blueberry barrens. This parasite was also found by other researchers in other parts of Maine and in Nova Scotia. The parasite oviposits in the maggots, which then mature and enter the pupal stage as usual. However, the maggot does not develop normally from here on out; come spring, an adult parasite emerges from the puparium. In a 1922 study, Opius ferrugineus Gahan was also found to emerge as a parasite from apple maggot puparia.[10]

Protective mimicry

The adult fly uses Batesian mimicry for defense. The fly has white markings on its thorax and a characteristic black banding shaped like an "F" on its wings. When threatened, it turns its wings 90° and moves them up and down while walking sideways; the combination mimics the appearance of the jumping spider due to the wing pattern in the new position appearing as additional legs, specifically the forelegs and pedipalps.[11]

Evolution

Rhagoletis pomonella is representative of evolution; the race that feeds on apples spontaneously evolved from the hawthorn-feeding race in 1800 to 1850 CE after apples were introduced into North America. The apple-feeding race does not normally feed on hawthorns, and the hawthorn-feeding race does not normally feed on apples. This constitutes a possible example of an early step towards the emergence of a new species, a case of sympatric speciation.[12] In addition, the hawthorn and apple host races of R. pomonella are able to produce viable offspring in a lab setting, but in nature, flies maintain their genetic integrity partly because of allochronic premating isolation from differently timed adult eclosion. Flies that infest apples eclose before flies that infest the hawthorn, which fruits later than apples.[5]

The emergence of the apple race of R. pomonella also appears to have driven formation of new races among its parasites.[13]

Interactions with humans

R. pomonella is a significant pest for apple crops because the species feeds on apples and lays eggs within the fruit.[12] The hatched maggots burrow tunnels within the apples and cause them to fall prematurely and create unsightly brown spots.

Rhagoletis mendax Curran or the blueberry maggot fly is a related species that is a pest of cultivated blueberries.[7]

Control

Infestation of maggots damages the fruit through the formation of winding tunnels. There is no external indication of maggots, but brown trails can be seen beneath the skin.[7] Therefore, to manage apple maggot infestation, farmers may destroy infested apples, hawthorn, and abandoned apple trees. Apple maggots may be killed by placing infested fruit in cold storage of 32 degrees Fahrenheit for forty days. Some biological control agents have not been found to be effective because apple maggots are hidden within the fruit.[7] Sprays for control of the codling moth, Cydia pomonella, have been able to partially control the apple maggot but cannot be completely depended on for commercially accepted control.[3] Naturally occurring parasitoids have been suggested to be used to manage the apple maggot. Opius downesi Gahan and Opius lectoides Gahan shifted from the show berry maggot to apple maggots in hawthorn, reducing apple maggot density at two study sites in Oregon, according to a paper published in 1985.[14]

See also

References

- Bush, Guy L. (1966). The Taxonomy, Cytology, and Evolution of Genus Rhagoletis in North America (Diptera, Tephritidae). Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University.

- AliNiazee. M.T. and R.L. Penrose. 1981. Apple maggot in Oregon : A possible threat to the Northwest apple industry. Bull. Entomol. Soc . Amer. 27 :245-246.

- AliNiazee. M.T. 1986. Managing the apple maggot. Rhagoletis pomella in the Pacific Northwest : An evaluation of possible options. Proc. 10 BC/WPRS Symp. on "Fruit Flies of Economic Importance." Hamburg. West Germany. 1984. Pp. 175-182.

- Hood, Glen R.; Yee, Wee (2013). "The geographic distribution of Rhagoletis pomonella (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Western United States: Introduced species or native population?". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 106 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1603/AN12074. S2CID 18789376.

- Rull, Juan; Aluja, Martin; Feder, Jeffrey; Berlocher, Stewart (2006-07-01). "Distribution and host range of hawthorn-infesting Rhagoletis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in Mexico". Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 99 (4): 662–672. doi:10.1603/0013-8746(2006)99[662:DAHROH]2.0.CO;2.

- Dean, R.W. and Chapman, P.J. (1973) Bionomics of the apple maggot in eastern New York. Search Agric. Entomol. Geneva No. 3, Geneva, N.Y. 1–62

- Weems, Jr., H.V. (January 2002). "Apple maggot – Rhagoletis pomonella (Walsh)". Entomology and Nematology UF. University of Florida. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- Illingworth, James Franklin; Herrick, Glenn Washington (1912). A Study of the Biology of the Apple Maggot (Rhagoletis pomonella): Together with an Investigation of Methods of Control. Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station.

- Opp, Susan B. & Prokopy, Ronald J. (2000). "Multiple mating and reproductive success of male and female apple maggot flies, Rhagoletis pomonella (Diptera: Tephritidae)". Journal of Insect Behavior. 13 (6): 901–914. doi:10.1023/A:1007818719058. S2CID 29962978.

- Porter, Benjamin Allen (1928). The Apple Maggot. US Department of Agriculture. pp. 29–30.

- Ricklefs, Robert E. & Miller, Gary L. (2000). Ecology. W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Feder, J. L. (1998) "The apple maggot fly, Rhagoletis pomonella: flies in the face of conventional wisdom about speciation?" In Howard, D. J. & Berlocher, S. H. (Eds.) Endless Forms: Species and Speciation. New York, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195109016

- Forbes, A. A.; Powell, T. H.Q.; Stelinski, L. L.; Smith, J. J. & Feder, J. L. (2009). "Sequential sympatric speciation across trophic levels". Science. 323 (5915): 776–779. Bibcode:2009Sci...323..776F. doi:10.1126/science.1166981. PMID 19197063. S2CID 10893849.

- AliNiazee. M.T. 1985 . Opiine (Hymenoptera:Braconidae) parasitoids of Rhagoletis pomonella and R. zephyria (Diptera:Tephritidae) in the Willamctte Valley, Oregon. Can. Entomol. 117: 163-166 .

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rhagoletis pomonella. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "Railroad Worm". |

- Popular Account Bugs of Wormy Apples, Part 2 Copyright © 1999 by Louise Kulzer

- Ohio State University Fact Sheet

- Apple Maggot Fly Traps – Ladd Research

- apple maggot fly on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Apple Maggot | Washington State Department of Agriculture

- CHAPTER 16-470 WAC APPLE MAGGOT QUARANTINE - SOIL - Washington State Department of Agriculture