Arthropod

An arthropod (/ˈɑːrθrəpɒd/, from Ancient Greek ἄρθρον (arthron) 'joint', and πούς (pous) 'foot' (gen. ποδός)) is an invertebrate animal having an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Euarthropoda,[1][3] which includes insects, arachnids, myriapods, and crustaceans. The term Arthropoda (/ɑːrˈθrɒpədə/) as originally proposed refers to a proposed grouping of Euarthropods and the phylum Onychophora.

Arthropods are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chitin, often mineralised with calcium carbonate. The arthropod body plan consists of segments, each with a pair of appendages. The rigid cuticle inhibits growth, so arthropods replace it periodically by moulting. Arthropods are bilaterally symmetrical and their body possesses an external skeleton. Some species have wings.

Their versatility has enabled arthropods to become the most species-rich members of all ecological guilds in most environments. They have over a million described species, making up more than 80 percent of all described living animal species, some of which, unlike most other animals, are very successful in dry environments. Arthropods range in size from the microscopic crustacean Stygotantulus up to the Japanese spider crab.

An arthropod's primary internal cavity is a haemocoel, which accommodates its interior organs, and through which its haemolymph – analogue of blood – circulates; it has an open circulatory system. Like their exteriors, the internal organs of arthropods are generally built of repeated segments. Their nervous system is "ladder-like", with paired ventral nerve cords running through all segments and forming paired ganglia in each segment. Their heads are formed by fusion of varying numbers of segments, and their brains are formed by fusion of the ganglia of these segments and encircle the esophagus. The respiratory and excretory systems of arthropods vary, depending as much on their environment as on the subphylum to which they belong.

Their vision relies on various combinations of compound eyes and pigment-pit ocelli: in most species the ocelli can only detect the direction from which light is coming, and the compound eyes are the main source of information, but the main eyes of spiders are ocelli that can form images and, in a few cases, can swivel to track prey. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many bristles known as setae that project through their cuticles.

Arthropods' methods of reproduction and development are diverse; all terrestrial species use internal fertilization, but this is often by indirect transfer of the sperm via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection. Aquatic species use either internal or external fertilization. Almost all arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions give birth to live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillars that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis to produce the adult form. The level of maternal care for hatchlings varies from nonexistent to the prolonged care provided by scorpions.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralians (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa. Overall, however, the basal relationships of animals are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated.

Arthropods contribute to the human food supply both directly as food, and more importantly indirectly as pollinators of crops. Some species are known to spread severe disease to humans, livestock, and crops.

Etymology

The word arthropod comes from the Greek ἄρθρον árthron, "joint", and πούς pous (gen. podos (ποδός)), i.e. "foot" or "leg", which together mean "jointed leg".[4] The designation "Arthropoda" was coined in 1848 by the German physiologist and zoologist Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold (1804–1885).[5][6]

Description

Arthropods are invertebrates with segmented bodies and jointed limbs.[7] The exoskeleton or cuticles consists of chitin, a polymer of glucosamine.[8] The cuticle of many crustaceans, beetle mites, and millipedes (except for bristly millipedes) is also biomineralized with calcium carbonate. Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occur in some opiliones.[9]

Diversity

Estimates of the number of arthropod species vary between 1,170,000 and 5 to 10 million and account for over 80 percent of all known living animal species.[10][11] The number of species remains difficult to determine. This is due to the census modeling assumptions projected onto other regions in order to scale up from counts at specific locations applied to the whole world. A study in 1992 estimated that there were 500,000 species of animals and plants in Costa Rica alone, of which 365,000 were arthropods.[12]

They are important members of marine, freshwater, land and air ecosystems, and are one of only two major animal groups that have adapted to life in dry environments; the other is amniotes, whose living members are reptiles, birds and mammals.[13] One arthropod sub-group, insects, is the most species-rich member of all ecological guilds in land and freshwater environments.[12] The lightest insects weigh less than 25 micrograms (millionths of a gram),[14] while the heaviest weigh over 70 grams (2.5 oz).[15] Some living crustaceans are much larger; for example, the legs of the Japanese spider crab may span up to 4 metres (13 ft),[14] with the heaviest of all living arthropods being the American lobster, topping out at over 20 kg (44 lbs).

Segmentation

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The last common ancestor of living arthropods probably consisted of a series of undifferentiated segments, each with a pair of appendages that functioned as limbs. However, all known living and fossil arthropods have grouped segments into tagmata in which segments and their limbs are specialized in various ways.[13]

The three-part appearance of many insect bodies and the two-part appearance of spiders is a result of this grouping;[16] in fact there are no external signs of segmentation in mites.[13] Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an acron at the front, ahead of the mouth, and a telson at the rear, behind the anus. The eyes are mounted on the acron.[13]

Originally it seems that each appendage-bearing segment had two separate pairs of appendages: an upper and a lower pair. These would later fuse into a single pair of biramous appendages, with the upper branch acting as a gill while the lower branch was used for locomotion.[17] In some segments of all known arthropods the appendages have been modified, for example to form gills, mouth-parts, antennae for collecting information,[16] or claws for grasping;[18] arthropods are "like Swiss Army knives, each equipped with a unique set of specialized tools."[13] In many arthropods, appendages have vanished from some regions of the body; it is particularly common for abdominal appendages to have disappeared or be highly modified.[13]

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata (includes spiders and scorpions), Crustacea (shrimps, lobsters, crabs, etc.), Tracheata (arthropods that breathe via channels into their bodies; includes insects and myriapods), and the extinct trilobites – have heads formed of various combinations of segments, with appendages that are missing or specialized in different ways.[13] In addition, some extinct arthropods, such as Marrella, belong to none of these groups, as their heads are formed by their own particular combinations of segments and specialized appendages.[19]

Working out the evolutionary stages by which all these different combinations could have appeared is so difficult that it has long been known as "the arthropod head problem".[20] In 1960, R. E. Snodgrass even hoped it would not be solved, as he found trying to work out solutions to be fun.[Note 1]

Exoskeleton

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of cuticle, a non-cellular material secreted by the epidermis.[13] Their cuticles vary in the details of their structure, but generally consist of three main layers: the epicuticle, a thin outer waxy coat that moisture-proofs the other layers and gives them some protection; the exocuticle, which consists of chitin and chemically hardened proteins; and the endocuticle, which consists of chitin and unhardened proteins. The exocuticle and endocuticle together are known as the procuticle.[22] Each body segment and limb section is encased in hardened cuticle. The joints between body segments and between limb sections are covered by flexible cuticle.[13]

The exoskeletons of most aquatic crustaceans are biomineralized with calcium carbonate extracted from the water. Some terrestrial crustaceans have developed means of storing the mineral, since on land they cannot rely on a steady supply of dissolved calcium carbonate.[23] Biomineralization generally affects the exocuticle and the outer part of the endocuticle.[22] Two recent hypotheses about the evolution of biomineralization in arthropods and other groups of animals propose that it provides tougher defensive armor,[24] and that it allows animals to grow larger and stronger by providing more rigid skeletons;[25] and in either case a mineral-organic composite exoskeleton is cheaper to build than an all-organic one of comparable strength.[25][26]

The cuticle may have setae (bristles) growing from special cells in the epidermis. Setae are as varied in form and function as appendages. For example, they are often used as sensors to detect air or water currents, or contact with objects; aquatic arthropods use feather-like setae to increase the surface area of swimming appendages and to filter food particles out of water; aquatic insects, which are air-breathers, use thick felt-like coats of setae to trap air, extending the time they can spend under water; heavy, rigid setae serve as defensive spines.[13]

Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, some still use hydraulic pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors;[27] for example, all spiders extend their legs hydraulically and can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level.[28]

Moulting

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods therefore replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size.[29]

The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle and thus detaches the old cuticle. This phase begins when the epidermis has secreted a new epicuticle to protect it from the enzymes, and the epidermis secretes the new exocuticle while the old cuticle is detaching. When this stage is complete, the animal makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air, and this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the old exocuticle was thinnest. It commonly takes several minutes for the animal to struggle out of the old cuticle. At this point, the new one is wrinkled and so soft that the animal cannot support itself and finds it very difficult to move, and the new endocuticle has not yet formed. The animal continues to pump itself up to stretch the new cuticle as much as possible, then hardens the new exocuticle and eliminates the excess air or water. By the end of this phase, the new endocuticle has formed. Many arthropods then eat the discarded cuticle to reclaim its materials.[29]

Because arthropods are unprotected and nearly immobilized until the new cuticle has hardened, they are in danger both of being trapped in the old cuticle and of being attacked by predators. Moulting may be responsible for 80 to 90% of all arthropod deaths.[29]

Internal organs

Arthropod bodies are also segmented internally, and the nervous, muscular, circulatory, and excretory systems have repeated components.[13] Arthropods come from a lineage of animals that have a coelom, a membrane-lined cavity between the gut and the body wall that accommodates the internal organs. The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom's main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton, which muscles compress in order to change the animal's shape and thus enable it to move. Hence the coelom of the arthropod is reduced to small areas around the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood flows.[30]

Respiration and circulation

Arthropods have open circulatory systems, although most have a few short, open-ended arteries. In chelicerates and crustaceans, the blood carries oxygen to the tissues, while hexapods use a separate system of tracheae. Many crustaceans, but few chelicerates and tracheates, use respiratory pigments to assist oxygen transport. The most common respiratory pigment in arthropods is copper-based hemocyanin; this is used by many crustaceans and a few centipedes. A few crustaceans and insects use iron-based hemoglobin, the respiratory pigment used by vertebrates. As with other invertebrates, the respiratory pigments of those arthropods that have them are generally dissolved in the blood and rarely enclosed in corpuscles as they are in vertebrates.[30]

The heart is typically a muscular tube that runs just under the back and for most of the length of the hemocoel. It contracts in ripples that run from rear to front, pushing blood forwards. Sections not being squeezed by the heart muscle are expanded either by elastic ligaments or by small muscles, in either case connecting the heart to the body wall. Along the heart run a series of paired ostia, non-return valves that allow blood to enter the heart but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front.[30]

Arthropods have a wide variety of respiratory systems. Small species often do not have any, since their high ratio of surface area to volume enables simple diffusion through the body surface to supply enough oxygen. Crustacea usually have gills that are modified appendages. Many arachnids have book lungs.[31] Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnids.[32]

Nervous system

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of ganglia from which sensory and motor nerves run to other parts of the segment. Although the pairs of ganglia in each segment often appear physically fused, they are connected by commissures (relatively large bundles of nerves), which give arthropod nervous systems a characteristic "ladder-like" appearance. The brain is in the head, encircling and mainly above the esophagus. It consists of the fused ganglia of the acron and one or two of the foremost segments that form the head – a total of three pairs of ganglia in most arthropods, but only two in chelicerates, which do not have antennae or the ganglion connected to them. The ganglia of other head segments are often close to the brain and function as part of it. In insects these other head ganglia combine into a pair of subesophageal ganglia, under and behind the esophagus. Spiders take this process a step further, as all the segmental ganglia are incorporated into the subesophageal ganglia, which occupy most of the space in the cephalothorax (front "super-segment").[33]

Excretory system

There are two different types of arthropod excretory systems. In aquatic arthropods, the end-product of biochemical reactions that metabolise nitrogen is ammonia, which is so toxic that it needs to be diluted as much as possible with water. The ammonia is then eliminated via any permeable membrane, mainly through the gills.[31] All crustaceans use this system, and its high consumption of water may be responsible for the relative lack of success of crustaceans as land animals.[34] Various groups of terrestrial arthropods have independently developed a different system: the end-product of nitrogen metabolism is uric acid, which can be excreted as dry material; the Malpighian tubule system filters the uric acid and other nitrogenous waste out of the blood in the hemocoel, and dumps these materials into the hindgut, from which they are expelled as feces.[34] Most aquatic arthropods and some terrestrial ones also have organs called nephridia ("little kidneys"), which extract other wastes for excretion as urine.[34]

Senses

The stiff cuticles of arthropods would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly setae, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste and smell, often by means of setae. Pressure sensors often take the form of membranes that function as eardrums, but are connected directly to nerves rather than to auditory ossicles. The antennae of most hexapods include sensor packages that monitor humidity, moisture and temperature.[35]

Optical

.png.webp)

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of compound eyes and pigment-cup ocelli ("little eyes"). In most cases ocelli are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, the main eyes of spiders are pigment-cup ocelli that are capable of forming images,[35] and those of jumping spiders can rotate to track prey.[36]

Compound eyes consist of fifteen to several thousand independent ommatidia, columns that are usually hexagonal in cross section. Each ommatidium is an independent sensor, with its own light-sensitive cells and often with its own lens and cornea.[35] Compound eyes have a wide field of view, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light.[37] On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within 20 centimetres (7.9 in) are most important to most arthropods.[35] Several arthropods have color vision, and that of some insects has been studied in detail; for example, the ommatidia of bees contain receptors for both green and ultra-violet.[35]

Most arthropods lack balance and acceleration sensors, and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. The self-righting behavior of cockroaches is triggered when pressure sensors on the underside of the feet report no pressure. However, many malacostracan crustaceans have statocysts, which provide the same sort of information as the balance and motion sensors of the vertebrate inner ear.[35]

The proprioceptors of arthropods, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well understood. However, little is known about what other internal sensors arthropods may have.[35]

Olfaction

Reproduction and development

A few arthropods, such as barnacles, are hermaphroditic, that is, each can have the organs of both sexes. However, individuals of most species remain of one sex their entire lives.[38] A few species of insects and crustaceans can reproduce by parthenogenesis, especially if conditions favor a "population explosion". However, most arthropods rely on sexual reproduction, and parthenogenetic species often revert to sexual reproduction when conditions become less favorable.[39] Aquatic arthropods may breed by external fertilization, as for example frogs do, or by internal fertilization, where the ova remain in the female's body and the sperm must somehow be inserted. All known terrestrial arthropods use internal fertilization. Opiliones (harvestmen), millipedes, and some crustaceans use modified appendages such as gonopods or penises to transfer the sperm directly to the female. However, most male terrestrial arthropods produce spermatophores, waterproof packets of sperm, which the females take into their bodies. A few such species rely on females to find spermatophores that have already been deposited on the ground, but in most cases males only deposit spermatophores when complex courtship rituals look likely to be successful.[38]

Most arthropods lay eggs,[38] but scorpions are ovoviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care.[40] Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or caterpillars, which do not have segmented limbs or hardened cuticles, and metamorphose into adult forms by entering an inactive phase in which the larval tissues are broken down and re-used to build the adult body.[41] Dragonfly larvae have the typical cuticles and jointed limbs of arthropods but are flightless water-breathers with extendable jaws.[42] Crustaceans commonly hatch as tiny nauplius larvae that have only three segments and pairs of appendages.[38]

Evolutionary history

Last common ancestor

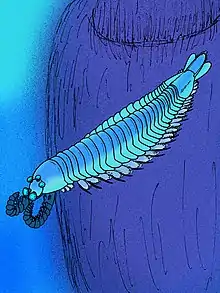

The last common ancestor of all arthropods is reconstructed as a modular organism with each module covered by its own sclerite (armor plate) and bearing a pair of biramous limbs.[43] However, whether the ancestral limb was uniramous or biramous is far from a settled debate. This Ur-arthropod had a ventral mouth, pre-oral antennae and dorsal eyes at the front of the body. It was assumed it was a non-discriminatory sediment feeder, processing whatever sediment came its way for food,[43] but fossil findings hints that the last common ancestor of both arthropods and priapulida shared the same specialized mouth apparatus; a circular mouth with rings of teeth used for capturing prey and was therefore carnivorous.[44]

Fossil record

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals Parvancorina and Spriggina, from around 555 million years ago, were arthropods.[45][46][47] Small arthropods with bivalve-like shells have been found in Early Cambrian fossil beds dating 541 to 539 million years ago in China and Australia.[48][49][50][51] The earliest Cambrian trilobite fossils are about 530 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and worldwide, suggesting that they had been around for quite some time.[52] Re-examination in the 1970s of the Burgess Shale fossils from about 505 million years ago identified many arthropods, some of which could not be assigned to any of the well-known groups, and thus intensified the debate about the Cambrian explosion.[53][54][55] A fossil of Marrella from the Burgess Shale has provided the earliest clear evidence of moulting.[56]

The earliest fossil crustaceans date from about 511 million years ago in the Cambrian,[58] and fossil shrimp from about 500 million years ago apparently formed a tight-knit procession across the seabed.[59] Crustacean fossils are common from the Ordovician period onwards.[60] They have remained almost entirely aquatic, possibly because they never developed excretory systems that conserve water.[34] In 2020 scientists announced the discovery of Kylinxia, a five-eyed ~5 cm long shrimp-like animal living 518 Mya that – with muliple distinctive features – appears to be a key ‘missing link’ of the evolution from Anomalocaris to true arthropods and could be at the evolutionary root of true arthropods.[57][61]

Arthropods provide the earliest identifiable fossils of land animals, from about 419 million years ago in the Late Silurian,[31] and terrestrial tracks from about 450 million years ago appear to have been made by arthropods.[62] Arthropods were well pre-adapted to colonize land, because their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.[63] Around the same time the aquatic, scorpion-like eurypterids became the largest ever arthropods, some as long as 2.5 metres (8.2 ft).[64]

The oldest known arachnid is the trigonotarbid Palaeotarbus jerami, from about 420 million years ago in the Silurian period.[65][Note 2] Attercopus fimbriunguis, from 386 million years ago in the Devonian period, bears the earliest known silk-producing spigots, but its lack of spinnerets means it was not one of the true spiders,[67] which first appear in the Late Carboniferous over 299 million years ago.[68] The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods provide a large number of fossil spiders, including representatives of many modern families.[69] Fossils of aquatic scorpions with gills appear in the Silurian and Devonian periods, and the earliest fossil of an air-breathing scorpion with book lungs dates from the Early Carboniferous period.[70]

The oldest definitive insect fossil is the Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti, dated at 396 to 407 million years ago, but its mandibles are of a type found only in winged insects, which suggests that the earliest insects appeared in the Silurian period.[71] The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about 300 million years ago, include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivores, detritivores and insectivores. Social termites and ants first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic.[72]

Evolutionary family tree

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist Sidnie Manton and others argued that arthropods are polyphyletic, in other words, that they do not share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod. Instead, they proposed that three separate groups of "arthropods" evolved separately from common worm-like ancestors: the chelicerates, including spiders and scorpions; the crustaceans; and the uniramia, consisting of onychophorans, myriapods and hexapods. These arguments usually bypassed trilobites, as the evolutionary relationships of this class were unclear. Proponents of polyphyly argued the following: that the similarities between these groups are the results of convergent evolution, as natural consequences of having rigid, segmented exoskeletons; that the three groups use different chemical means of hardening the cuticle; that there were significant differences in the construction of their compound eyes; that it is hard to see how such different configurations of segments and appendages in the head could have evolved from the same ancestor; and that crustaceans have biramous limbs with separate gill and leg branches, while the other two groups have uniramous limbs in which the single branch serves as a leg.[74]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Further analysis and discoveries in the 1990s reversed this view, and led to acceptance that arthropods are monophyletic, in other words they do share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod.[75][76] For example, Graham Budd's analyses of Kerygmachela in 1993 and of Opabinia in 1996 convinced him that these animals were similar to onychophorans and to various Early Cambrian "lobopods", and he presented an "evolutionary family tree" that showed these as "aunts" and "cousins" of all arthropods.[73][77] These changes made the scope of the term "arthropod" unclear, and Claus Nielsen proposed that the wider group should be labelled "Panarthropoda" ("all the arthropods") while the animals with jointed limbs and hardened cuticles should be called "Euarthropoda" ("true arthropods").[78]

A contrary view was presented in 2003, when Jan Bergström and Xian-Guang Hou argued that, if arthropods were a "sister-group" to any of the anomalocarids, they must have lost and then re-evolved features that were well-developed in the anomalocarids. The earliest known arthropods ate mud in order to extract food particles from it, and possessed variable numbers of segments with unspecialized appendages that functioned as both gills and legs. Anomalocarids were, by the standards of the time, huge and sophisticated predators with specialized mouths and grasping appendages, fixed numbers of segments some of which were specialized, tail fins, and gills that were very different from those of arthropods. This reasoning implies that Parapeytoia, which has legs and a backward-pointing mouth like that of the earliest arthropods, is a more credible closest relative of arthropods than is Anomalocaris.[79] In 2006, they suggested that arthropods were more closely related to lobopods and tardigrades than to anomalocarids.[80] In 2014, research indicated that tardigrades were more closely related to arthropods than velvet worms.[81]

| Protostomes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Higher up the "family tree", the Annelida have traditionally been considered the closest relatives of the Panarthropoda, since both groups have segmented bodies, and the combination of these groups was labelled Articulata. There had been competing proposals that arthropods were closely related to other groups such as nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades, but these remained minority views because it was difficult to specify in detail the relationships between these groups.

In the 1990s, molecular phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences produced a coherent scheme showing arthropods as members of a superphylum labelled Ecdysozoa ("animals that moult"), which contained nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades but excluded annelids. This was backed up by studies of the anatomy and development of these animals, which showed that many of the features that supported the Articulata hypothesis showed significant differences between annelids and the earliest Panarthropods in their details, and some were hardly present at all in arthropods. This hypothesis groups annelids with molluscs and brachiopods in another superphylum, Lophotrochozoa.

If the Ecdysozoa hypothesis is correct, then segmentation of arthropods and annelids either has evolved convergently or has been inherited from a much older ancestor and subsequently lost in several other lineages, such as the non-arthropod members of the Ecdysozoa.[84][82]

Classification

Arthropods belong to phylum Euarthropoda.[3][85] The phylum is sometimes called Arthropoda, but strictly this term denotes a (putative - see Tactopoda) clade that also encompasses the phylum Onychophora.[1]

Euarthropoda is typically subdivided into five subphyla, of which one is extinct:[86]

- Trilobites are a group of formerly numerous marine animals that disappeared in the Permian–Triassic extinction event, though they were in decline prior to this killing blow, having been reduced to one order in the Late Devonian extinction.

- Chelicerates include horseshoe crabs, spiders, mites, scorpions and related organisms. They are characterised by the presence of chelicerae, appendages just above / in front of the mouth. Chelicerae appear in scorpions and horseshoe crabs as tiny claws that they use in feeding, but those of spiders have developed as fangs that inject venom.

- Myriapods comprise millipedes, centipedes, and their relatives and have many body segments, each segment bearing one or two pairs of legs (or in a few cases being legless). They are sometimes grouped with the hexapods.

- Crustaceans are primarily aquatic (a notable exception being woodlice) and are characterised by having biramous appendages. They include lobsters, crabs, barnacles, crayfish, shrimp and many others.

- Hexapods comprise insects and three small orders of insect-like animals with six thoracic legs. They are sometimes grouped with the myriapods, in a group called Uniramia, though genetic evidence tends to support a closer relationship between hexapods and crustaceans.

Aside from these major groups, there are also a number of fossil forms, mostly from the Early Cambrian, which are difficult to place, either from lack of obvious affinity to any of the main groups or from clear affinity to several of them. Marrella was the first one to be recognized as significantly different from the well-known groups.[19]

The phylogeny of the major extant arthropod groups has been an area of considerable interest and dispute.[87] Recent studies strongly suggest that Crustacea, as traditionally defined, is paraphyletic, with Hexapoda having evolved from within it,[88][89] so that Crustacea and Hexapoda form a clade, Pancrustacea. The position of Myriapoda, Chelicerata and Pancrustacea remains unclear as of April 2012. In some studies, Myriapoda is grouped with Chelicerata (forming Myriochelata);[90][91] in other studies, Myriapoda is grouped with Pancrustacea (forming Mandibulata),[88] or Myriapoda may be sister to Chelicerata plus Pancrustacea.[89]

|

traditional Crustacea |

The placement of the extinct trilobites is also a frequent subject of dispute.[92] One of the newer hypotheses is that the chelicerae have originated from the same pair of appendages that evolved into antennae in the ancestors of Mandibulata, which would place trilobites, which had antennae, closer to Mandibulata than Chelicerata.[93]

Since the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature recognises no priority above the rank of family, many of the higher-level groups can be referred to by a variety of different names.[94]

Interaction with humans

Crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns have long been part of human cuisine, and are now raised commercially.[95] Insects and their grubs are at least as nutritious as meat, and are eaten both raw and cooked in many cultures, though not most European, Hindu, and Islamic cultures.[96][97] Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia,[98][99][100] and by the Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela, after the highly irritant hairs – the spider's main defense system – are removed.[101] Humans also unintentionally eat arthropods in other foods,[102] and food safety regulations lay down acceptable contamination levels for different kinds of food material.[Note 3][Note 4] The intentional cultivation of arthropods and other small animals for human food, referred to as minilivestock, is now emerging in animal husbandry as an ecologically sound concept.[106] Commercial butterfly breeding provides Lepidoptera stock to butterfly conservatories, educational exhibits, schools, research facilities, and cultural events.

However, the greatest contribution of arthropods to human food supply is by pollination: a 2008 study examined the 100 crops that FAO lists as grown for food, and estimated pollination's economic value as €153 billion, or 9.5 per cent of the value of world agricultural production used for human food in 2005.[107] Besides pollinating, bees produce honey, which is the basis of a rapidly growing industry and international trade.[108]

The red dye cochineal, produced from a Central American species of insect, was economically important to the Aztecs and Mayans.[109] While the region was under Spanish control, it became Mexico's second most-lucrative export,[110] and is now regaining some of the ground it lost to synthetic competitors.[111] Shellac, a resin secreted by a species of insect native to southern Asia, was historically used in great quantities for many applications in which it has mostly been replaced by synthetic resins, but it is still used in woodworking and as a food additive. The blood of horseshoe crabs contains a clotting agent, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate, which is now used to test that antibiotics and kidney machines are free of dangerous bacteria, and to detect spinal meningitis and some cancers.[112] Forensic entomology uses evidence provided by arthropods to establish the time and sometimes the place of death of a human, and in some cases the cause.[113] Recently insects have also gained attention as potential sources of drugs and other medicinal substances.[114]

The relative simplicity of the arthropods' body plan, allowing them to move on a variety of surfaces both on land and in water, have made them useful as models for robotics. The redundancy provided by segments allows arthropods and biomimetic robots to move normally even with damaged or lost appendages.[115][116]

| Disease[117] | Insect | Cases per year | Deaths per year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria | Anopheles mosquito | 267 M | 1 to 2 M |

| Dengue fever | Aedes mosquito | ? | ? |

| Yellow fever | Aedes mosquito | 4,432 | 1,177 |

| Filariasis | Culex mosquito | 250 M | unknown |

Although arthropods are the most numerous phylum on Earth, and thousands of arthropod species are venomous, they inflict relatively few serious bites and stings on humans. Far more serious are the effects on humans of diseases like malaria carried by blood-sucking insects. Other blood-sucking insects infect livestock with diseases that kill many animals and greatly reduce the usefulness of others.[117] Ticks can cause tick paralysis and several parasite-borne diseases in humans.[118] A few of the closely related mites also infest humans, causing intense itching,[119] and others cause allergic diseases, including hay fever, asthma, and eczema.[120]

Many species of arthropods, principally insects but also mites, are agricultural and forest pests.[121][122] The mite Varroa destructor has become the largest single problem faced by beekeepers worldwide.[123] Efforts to control arthropod pests by large-scale use of pesticides have caused long-term effects on human health and on biodiversity.[124] Increasing arthropod resistance to pesticides has led to the development of integrated pest management using a wide range of measures including biological control.[121] Predatory mites may be useful in controlling some mite pests.[125][126]

As predators

Even amongst arthropods usually thought of as obligate predators, floral food sources (nectar and to a lesser degree pollen) are often useful adjunct sources.[127] It was noticed in one study[128] that adult Adalia bipunctata (predator and common biocontrol of Ephestia kuehniella) could survive on flowers but never completed the life cycle, so a meta-analysis[127] was done to find such an overall trend in previously published data, if it existed. In some cases floral resources are outright necessary.[127] Overall, floral resources (and an imitation, i.e. sugar water) increase longevity and fecundity, meaning even predatory population numbers can depend on non-prey food abundance.[127] Thus biocontrol success may surprisingly depend on nearby flowers.[127]

See also

Notes

- "It would be too bad if the question of head segmentation ever should be finally settled; it has been for so long such fertile ground for theorizing that arthropodists would miss it as a field for mental exercise."[21]

- The fossil was originally named Eotarbus but was renamed when it was realized that a Carboniferous arachnid had already been named Eotarbus.[66]

- For a mention of insect contamination in an international food quality standard, see sections 3.1.2 and 3.1.3 of Codex 152 of 1985 of the Codex Alimentarius[103]

- For examples of quantified acceptable insect contamination levels in food see the last entry (on "Wheat Flour") and the definition of "Extraneous material" in Codex Alimentarius,[104] and the standards published by the FDA.[105]

References

- Ortega-Hernández, J. (February 2016), "Making sense of 'lower' and 'upper' stem-group Euarthropoda, with comments on the strict use of the name Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848", Biological Reviews, 91 (1): 255–273, doi:10.1111/brv.12168, PMID 25528950, S2CID 7751936

- Garwood, R.; Sutton, M. (18 February 2012), "The enigmatic arthropod Camptophyllia", Palaeontologia Electronica, 15 (2): 12, doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00174, archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2013, retrieved 11 June 2012

- Reference showing that Euarthropoda is a phylum: Smith, Martin R. (2014). "Hallucigenia's onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda" (PDF). Nature. 514 (7522): 363–366. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..363S. doi:10.1038/nature13576. PMID 25132546. S2CID 205239797. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2018-11-24.

- "Arthropoda". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2013-03-07. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Siebold, C. Th. v. (1848). Lehrbuch der vergleichenden Anatomie der Wirbellosen Thiere [Textbook of Comparative Anatomy of Invertebrate Animals] (in German). Berlin, (Germany): Veit & Co. p. 4. From p. 4: "Arthropoda. Thiere mit vollkommen symmetrischer Form und gegliederten Bewegungsorganen. Centralmasse des Nervensystems besteht aus einem den Schlund umfassenden Ganglienring und einer von diesem ausgehenden Bauch-Ganglienkette." (Arthropoda. Animals with completely symmetric form and articulated organs of movement. Central mass of the nervous system consists of a ring of ganglia surrounding the esophagus and an abdominal chain of ganglia extending from this [ring of ganglia].)

- Hegna, Thomas A.; Legg, David A.; Møller, Ole Sten; Van Roy, Peter; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy (November 19, 2013). "The correct authorship of the taxon name 'Arthropoda'". Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny. 71 (2): 71–74.

- Valentine, J. W. (2004), On the Origin of Phyla, University of Chicago Press, p. 33, ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7

- Cutler, B. (August 1980), "Arthropod cuticle features and arthropod monophyly", Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 36 (8): 953, doi:10.1007/BF01953812

- Kovoor, J. (1978). "Natural calcification of the prosomatic endosternite in the Phalangiidae (Arachnida:Opiliones)". Calcified Tissue Research. 26 (3): 267–9. doi:10.1007/BF02013269. PMID 750069. S2CID 23119386.

- Thanukos, Anna, The Arthropod Story, University of California, Berkeley, archived from the original on 2008-06-16, retrieved 2008-09-29

- Ødegaard, Frode (December 2000), "How many species of arthropods? Erwin's estimate revised." (PDF), Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 71 (4): 583–597, doi:10.1006/bijl.2000.0468, archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-26, retrieved 2010-05-06

- Thompson, J. N. (1994), The Coevolutionary Process, University of Chicago Press, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-226-79760-1

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 518–522

- Schmidt-Nielsen, Knut (1984), "The strength of bones and skeletons", Scaling: Why is Animal Size So Important?, Cambridge University Press, pp. 42–55, ISBN 978-0-521-31987-4

- Williams, D.M. (April 21, 2001), "Largest", Book of Insect Records, University of Florida, archived from the original on July 18, 2011, retrieved 2009-06-10

- Gould (1990), pp. 102–106

- "Giant sea creature hints at early arthropod evolution". 2015-03-11. Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- Shubin, Neil; Tabin, C.; Carroll, Sean (2000), "Fossils, Genes and the Evolution of Animal Limbs", in Gee, H. (ed.), Shaking the Tree: Readings from Nature in the History of Life, University of Chicago Press, p. 110, ISBN 978-0-226-28497-2

- Whittington, H. B. (1971), "Redescription of Marrella splendens (Trilobitoidea) from the Burgess Shale, Middle Cambrian, British Columbia", Geological Survey of Canada Bulletin, 209: 1–24 Summarised in Gould (1990), pp. 107–121.

- Budd, G. E. (16 May 2002), "A palaeontological solution to the arthropod head problem", Nature, 417 (6886): 271–275, Bibcode:2002Natur.417..271B, doi:10.1038/417271a, PMID 12015599, S2CID 4310080

- Snodgrass, R. E. (1960), "Facts and theories concerning the insect head", Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 142: 1–61

- Wainwright, S. A.; Biggs, W. D. & Gosline, J. M. (1982), Mechanical Design in Organisms, Princeton University Press, pp. 162–163, ISBN 978-0-691-08308-7

- Lowenstam, H. A. & Weiner, S. (1989), On biomineralization, Oxford University Press, p. 111, ISBN 978-0-19-504977-0

- Dzik, J (2007), "The Verdun Syndrome: simultaneous origin of protective armour and infaunal shelters at the Precambrian–Cambrian transition", in Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Komarower, Patricia (eds.), The Rise and Fall of the Ediacaran Biota (PDF), Special publications, 286, London: Geological Society, pp. 405–414, doi:10.1144/SP286.30, ISBN 9781862392335, OCLC 156823511CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cohen, B. L. (2005), "Not armour, but biomechanics, ecological opportunity and increased fecundity as keys to the origin and expansion of the mineralized benthic metazoan fauna" (PDF), Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 85 (4): 483–490, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00507.x, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-03, retrieved 2008-09-25

- Bengtson, S. (2004), Lipps, J. H.; Waggoner, B. M. (eds.), "Early skeletal fossils" (PDF), The Paleontological Society Papers, Volume 10: neoproterozoic-cambrian biological revolutions: 67–78, doi:10.1017/S1089332600002345, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-03

- Barnes, R. S. K.; Calow, P.; Olive, P.; Golding, D. & Spicer, J. (2001), "Invertebrates with Legs: the Arthropods and Similar Groups", The Invertebrates: A Synthesis, Blackwell Publishing, p. 168, ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1

- Parry, D. A. & Brown, R. H. J. (1959), "The hydraulic mechanism of the spider leg" (PDF), Journal of Experimental Biology, 36 (2): 423–433, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-03, retrieved 2008-09-25

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 527–528

- Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Greg (2011). "Early Terrestrial Animals, Evolution, and Uncertainty". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 4 (3): 489–501. doi:10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 530, 733

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 531–532

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 529–530

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 532–537

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 578–580

- Völkel, R.; Eisner, M.; Weible, K. J. (June 2003). "Miniaturized imaging systems" (PDF). Microelectronic Engineering. 67–68: 461–472. doi:10.1016/S0167-9317(03)00102-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-01.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 537–539

- Olive, P. J. W. (2001). "Reproduction and LifeCycles in Invertebrates". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0003649. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- Lourenço, W. R. (2002), "Reproduction in scorpions, with special reference to parthenogenesis", in Toft, S.; Scharff, N. (eds.), European Arachnology 2000 (PDF), Aarhus University Press, pp. 71–85, ISBN 978-87-7934-001-5, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-03, retrieved 2008-09-28

- Truman, J. W. & Riddiford, L. M. (September 1999), "The origins of insect metamorphosis" (PDF), Nature, 401 (6752): 447–452, Bibcode:1999Natur.401..447T, doi:10.1038/46737, PMID 10519548, S2CID 4327078, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-10-03, retrieved 2008-09-28

- Smith, G., Diversity and Adaptations of the Aquatic Insects (PDF), New College of Florida, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008, retrieved 2008-09-28

- Bergström, Jan; Hou, Xian-Guang (2005), "Early Palaeozoic non-lamellipedian arthropods", in Stefan Koenemann; Ronald A. Jenner (eds.), Crustacea and Arthropod Relationships, Crustacean Issues, 16, Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, pp. 73–93, doi:10.1201/9781420037548.ch4, ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6

- "Arthropod ancestor had the mouth of a penis worm - Natural History Museum". Archived from the original on 2017-02-02. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- Glaessner, M. F. (1958). "New fossils from the base of the Cambrian in South Australia" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 81: 185–188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16.

- Lin, J. P.; Gon, S. M.; Gehling, J. G.; Babcock, L. E.; Zhao, Y. L.; Zhang, X. L.; Hu, S. X.; Yuan, J. L.; Yu, M. Y.; Peng, J. (2006). "A Parvancorina-like arthropod from the Cambrian of South China". Historical Biology. 18 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1080/08912960500508689. S2CID 85821717.

- McMenamin, M.A.S (2003), "Spriggina is a trilobitoid ecdysozoan" (abstract), Abstracts with Programs, 35 (6): 105, archived from the original on 2008-08-30, retrieved 2008-10-21

- Braun, A.; J. Chen; D. Waloszek; A. Maas (2007), "First Early Cambrian Radiolaria" (PDF), Special Publications, 286 (1): 143–149, Bibcode:2007GSLSP.286..143B, doi:10.1144/SP286.10, S2CID 129651908, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18

- Yuan, X.; Xiao, S.; Parsley, R. L.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Z.; Hu, J. (April 2002). "Towering sponges in an Early Cambrian Lagerstätte: Disparity between nonbilaterian and bilaterian epifaunal tierers at the Neoproterozoic-Cambrian transition". Geology. 30 (4): 363–366. Bibcode:2002Geo....30..363Y. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<0363:TSIAEC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- Skovsted, Christian; Brock, Glenn; Paterson, John (2006), "Bivalved arthropods from the Lower Cambrian Mernmerna Formation of South Australia and their implications for the identification of Cambrian 'small shelly fossils'", Association of Australasian Palaeontologists Memoirs, 32: 7–41, ISSN 0810-8889

- Betts, Marissa; Topper, Timothy; Valentine, James; Skovsted, Christian; Paterson, John; Brock, Glenn (January 2014), "A new early Cambrian bradoriid (Arthropoda) assemblage from the northern Flinders Ranges, South Australia", Gondwana Research, 25 (1): 420–437, Bibcode:2014GondR..25..420B, doi:10.1016/j.gr.2013.05.007

- Lieberman, B. S. (March 1, 1999), "Testing the Darwinian legacy of the Cambrian radiation using trilobite phylogeny and biogeography", Journal of Paleontology, 73 (2): 176, doi:10.1017/S0022336000027700, archived from the original on October 19, 2008, retrieved October 21, 2008

- Whittington, H. B. (1979). Early arthropods, their appendages and relationships. In M. R. House (Ed.), The origin of major invertebrate groups (pp. 253–268). The Systematics Association Special Volume, 12. London: Academic Press.

- Whittington, H.B.; Geological Survey of Canada (1985), The Burgess Shale, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-660-11901-4, OCLC 15630217

- Gould (1990)

- García-Bellido, D. C.; Collins, D. H. (May 2004), "Moulting arthropod caught in the act", Nature, 429 (6987): 40, Bibcode:2004Natur.429...40G, doi:10.1038/429040a, PMID 15129272, S2CID 40015864

- "A 520-million-year-old, five-eyed fossil reveals arthropod origin". phys.org. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Budd, G. E.; Butterfield, N. J. & Jensen, S. (December 2001), "Crustaceans and the "Cambrian Explosion"", Science, 294 (5549): 2047, doi:10.1126/science.294.5549.2047a, PMID 11739918

- Callaway, E. (9 October 2008), Fossilised shrimp show earliest group behaviour, New Scientist, archived from the original on 15 October 2008, retrieved 2008-10-21

- Zhang, X.-G.; Siveter, D. J.; Waloszek, D. & Maas, A. (October 2007), "An epipodite-bearing crown-group crustacean from the Lower Cambrian", Nature, 449 (7162): 595–598, Bibcode:2007Natur.449..595Z, doi:10.1038/nature06138, PMID 17914395, S2CID 4329196

- Zeng, Han; Zhao, Fangchen; Niu, Kecheng; Zhu, Maoyan; Huang, Diying (December 2020). "An early Cambrian euarthropod with radiodont-like raptorial appendages". Nature. 588 (7836): 101–105. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33149303. S2CID 226248177. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Pisani, D.; Poling, L. L.; Lyons-Weiler M.; Hedges, S. B. (2004), "The colonization of land by animals: molecular phylogeny and divergence times among arthropods", BMC Biology, 2: 1, doi:10.1186/1741-7007-2-1, PMC 333434, PMID 14731304

- Cowen, R. (2000), History of Life (3rd ed.), Blackwell Science, p. 126, ISBN 978-0-632-04444-3

- Braddy, S. J.; Markus Poschmann, M. & Tetlie, O. E. (2008), "Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod", Biology Letters, 4 (1): 106–109, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491, PMC 2412931, PMID 18029297

- Dunlop, J. A. (September 1996), "A trigonotarbid arachnid from the Upper Silurian of Shropshire" (PDF), Palaeontology, 39 (3): 605–614, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-16

- Dunlop, J. A. (1999), "A replacement name for the trigonotarbid arachnid Eotarbus Dunlop", Palaeontology, 42 (1): 191, doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00068

- Selden, P. A. & Shear, W. A. (December 2008), "Fossil evidence for the origin of spider spinnerets", PNAS, 105 (52): 20781–5, Bibcode:2008PNAS..10520781S, doi:10.1073/pnas.0809174106, PMC 2634869, PMID 19104044

- Selden, P. A. (February 1996), "Fossil mesothele spiders", Nature, 379 (6565): 498–499, Bibcode:1996Natur.379..498S, doi:10.1038/379498b0, S2CID 26323977

- Vollrath, F. & Selden, P. A. (December 2007), "The Role of Behavior in the Evolution of Spiders, Silks, and Webs" (PDF), Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 38: 819–846, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110221, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-09

- Jeram, A. J. (January 1990), "Book-lungs in a Lower Carboniferous scorpion", Nature, 343 (6256): 360–361, Bibcode:1990Natur.343..360J, doi:10.1038/343360a0, S2CID 4327169

- Engel, M. S.; Grimaldi, D. A. (February 2004), "New light shed on the oldest insect", Nature, 427 (6975): 627–630, Bibcode:2004Natur.427..627E, doi:10.1038/nature02291, PMID 14961119, S2CID 4431205

- Labandeira, C. & Eble, G. J. (2000), "The Fossil Record of Insect Diversity and Disparity", in Anderson, J.; Thackeray, F.; van Wyk, B. & de Wit, M. (eds.), Gondwana Alive: Biodiversity and the Evolving Biosphere (PDF), Witwatersrand University Press, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-11, retrieved 2008-10-21

- Budd, G. E. (1996). "The morphology of Opabinia regalis and the reconstruction of the arthropod stem-group". Lethaia. 29 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01831.x.

- Gillott, C. (1995), Entomology, Springer, pp. 17–19, ISBN 978-0-306-44967-3

- Adrain, J. (15 March 1999), Book Review: Arthropod Fossils and Phylogeny, edited by Gregory D. Edgecomb, Palaeontologia Electronica, archived from the original on 8 September 2008, retrieved 2008-09-28 The book is Labandiera, Conrad C.; Edgecombe, Gregory (1998), G. D. (ed.), "Arthropod Fossils and Phylogeny", PALAIOS, Columbia University Press, 14 (4): 347, Bibcode:1999Palai..14..405L, doi:10.2307/3515467, JSTOR 3515467

- Chen, J.-Y.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Ramsköld, L.; Zhou, G.-Q. (2 June 1995), "Head segmentation in Early Cambrian Fuxianhuia: implications for arthropod evolution", Science, 268 (5215): 1339–1343, Bibcode:1995Sci...268.1339C, doi:10.1126/science.268.5215.1339, PMID 17778981, S2CID 32142337

- Budd, G. E. (1993). "A Cambrian gilled lobopod from Greenland". Nature. 364 (6439): 709–711. Bibcode:1993Natur.364..709B. doi:10.1038/364709a0. S2CID 4341971.

- Nielsen, C. (2001). Animal Evolution: Interrelationships of the Living Phyla (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-0-19-850681-2.

- Bergström, J. & Hou, X.-G. (2003). "Arthropod origins" (PDF). Bulletin of Geosciences. 78 (4): 323–334. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- Hou, X.-G.; Bergström, J. & Jie, Y. (2006), "Distinguishing anomalocaridids from arthropods and priapulids", Geological Journal, 41 (3–4): 259–269, doi:10.1002/gj.1050

- "Misunderstood worm-like fossil finds its place in the Tree of Life". 17 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Telford, M. J.; Bourlat, S. J.; Economou, A.; Papillon, D. & Rota-Stabelli, O. (January 2008). "The evolution of the Ecdysozoa". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 363 (1496): 1529–1537. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2243. PMC 2614232. PMID 18192181.

- Vaccari, N. E.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Escudero, C. (29 July 2004), "Cambrian origins and affinities of an enigmatic fossil group of arthropods", Nature, 430 (6999): 554–557, Bibcode:2004Natur.430..554V, doi:10.1038/nature02705, PMID 15282604, S2CID 4419235

- Schmidt-Rhaesa, A.; Bartolomaeus, T.; Lemburg, C.; Ehlers, U. & Garey, J. R. (January 1999). "The position of the Arthropoda in the phylogenetic system". Journal of Morphology. 238 (3): 263–285. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199812)238:3<263::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 29852696.

- Smith, Frank W.; Goldstein, Bob (May 2017). "Segmentation in Tardigrada and diversification of segmental patterns in Panarthropoda" (PDF). Arthropod Structure & Development. 46 (3): 328–340. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.005. PMID 27725256. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-02. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- "Arthropoda". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- Carapelli, Antonio; Liò, Pietro; Nardi, Francesco; van der Wath, Elizabeth; Frati, Francesco (16 August 2007). "Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial protein coding genes confirms the reciprocal paraphyly of Hexapoda and Crustacea". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (Suppl 2): S8. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S8. PMC 1963475. PMID 17767736.

- Regier, Jerome C.; Shultz, J. W.; Zwick, A.; Hussey, A.; Ball, B.; Wetzer, R.; Martin, J. W.; Cunningham, C. W.; et al. (201). "Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences". Nature. 463 (7284): 1079–1084. Bibcode:2010Natur.463.1079R. doi:10.1038/nature08742. PMID 20147900. S2CID 4427443.

- von Reumont, Bjoern M.; Jenner, Ronald A.; Wills, Matthew A.; Dell’Ampio, Emiliano; Pass, Günther; Ebersberger, Ingo; Meyer, Benjamin; Koenemann, Stefan; Iliffe, Thomas M.; Stamatakis, Alexandros; Niehuis, Oliver; Meusemann, Karen; Misof, Bernhard (2011), "Pancrustacean phylogeny in the light of new phylogenomic data: support for Remipedia as the possible sister group of Hexapoda", Molecular Biology and Evolution, 29 (3): 1031–45, doi:10.1093/molbev/msr270, PMID 22049065

- Hassanin, Alexandre (2006). "Phylogeny of Arthropoda inferred from mitochondrial sequences: Strategies for limiting the misleading effects of multiple changes in pattern and rates of substitution" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 38 (1): 100–116. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.012. PMID 16290034. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-01-10. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- Giribet, G.; Richter, S.; Edgecombe, G. D.; Wheeler, W. C. (2005). The position of crustaceans within Arthropoda – Evidence from nine molecular loci and morphology (PDF). Crustacean Issues. 16. pp. 307–352. doi:10.1201/9781420037548.ch13. ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-09-16. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- Jenner, R. A. (April 2006). "Challenging received wisdoms: Some contributions of the new microscopy to the new animal phylogeny". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (2): 93–103. doi:10.1093/icb/icj014. PMID 21672726.

- Dunlop, Jason A. (31 January 2011), "Fossil Focus: Chelicerata", PALAEONTOLOGY[online], archived from the original on 12 September 2017, retrieved 15 March 2018

- "Arthropoda". peripatus.gen.nz. Archived from the original on 2007-02-07.

- Wickins, J. F. & Lee, D. O'C. (2002). Crustacean Farming: Ranching and Culture (2nd ed.). Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-632-05464-0. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- Bailey, S., Bugfood II: Insects as Food!?!, University of Kentucky Department of Entomology, archived from the original on 2008-12-16, retrieved 2008-10-03

- Unger, L., Bugfood III: Insect Snacks from Around the World, University of Kentucky Department of Entomology, archived from the original on 10 October 2008, retrieved 2008-10-03

- Rigby, R. (September 21, 2002), "Tuck into a Tarantula", Sunday Telegraph, archived from the original on July 18, 2009, retrieved 2009-08-24

- Spiderwomen serve up Cambodia's creepy caviar, ABC News Online, September 2, 2002, archived from the original on June 3, 2008, retrieved 2009-08-24

- Ray, N. (2002). Lonely Planet Cambodia. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 308. ISBN 978-1-74059-111-9.

- Weil, C. (2006), Fierce Food, Plume, ISBN 978-0-452-28700-6, archived from the original on 2011-05-11, retrieved 2008-10-03

- Taylor, R. L. (1975), Butterflies in My Stomach (or: Insects in Human Nutrition), Woodbridge Press Publishing Company, Santa Barbara, California

- Codex commission for food hygiene (1985), "Codex Standard 152 of 1985 (on "Wheat Flour")" (PDF), Codex Alimentarius, Food and Agriculture Organization, archived (PDF) from the original on 2010-12-31, retrieved 2010-05-08.

- "Complete list of Official Standards", Codex Alimentarius, Food and Agriculture Organization, archived from the original on 2010-01-31, retrieved 2010-05-08

- The Food Defect Action Levels, U. S. Food and Drug Administration, archived from the original on 18 December 2006, retrieved 2006-12-16

- Paoletti, M. G. (2005), Ecological implications of minilivestock: potential of insects, rodents, frogs, and snails, Science Publishers, p. 648, ISBN 978-1-57808-339-8

- Gallai, N.; Salles, J.-M.; Settele, J.; Vaissière, B. E. (August 2008). "Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline" (PDF). Ecological Economics. 68 (3): 810–821. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2018-11-24. Free summary at Gallai, N.; Salles, J.; Settele, J.; Vaissiere, B. (2009), "Economic value of insect pollination worldwide estimated at 153 billion euros", Ecological Economics, 68 (3): 810–821, doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014, archived from the original on 2008-12-03, retrieved 2008-10-03

- Apiservices — International honey market — World honey production, imports & exports, archived from the original on 2008-12-06, retrieved 2008-10-03

- Threads In Tyme, LTD, Time line of fabrics, archived from the original on October 28, 2005, retrieved 2005-07-14

- Jeff Behan, The bug that changed history, archived from the original on 21 June 2006, retrieved 2006-06-26

- Canary Islands cochineal producers homepage, archived from the original on 24 June 2005, retrieved 2005-07-14

- Heard, W., Coast (PDF), University of South Florida, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-19, retrieved 2008-08-25

- Hall, R. D.; Castner, J. L. (2000), "Introduction", in Byrd, J. H.; Castner, J. L. (eds.), Forensic Entomology: the Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations, CRC Press, pp. 3–4, ISBN 978-0-8493-8120-1

- Dossey, Aaron (December 2010), "Insects and their chemical weaponry: New potential for drug discovery", Natural Product Reports, 27 (12): 1737–1757, doi:10.1039/C005319H, PMID 20957283

- Spagna, J. C.; Goldman D. I.; Lin P.-C.; Koditschek D. E.; R. J. Full (March 2007), "Distributed mechanical feedback in arthropods and robots simplifies control of rapid running on challenging terrain" (PDF), Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 2 (1): 9–18, Bibcode:2007BiBi....2....9S, doi:10.1088/1748-3182/2/1/002, PMID 17671322, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-10

- Kazuo Tsuchiya; Shinya Aoi & Katsuyoshi Tsujita (2006), "A Turning Strategy of a Multi-legged Locomotion Robot", Adaptive Motion of Animals and Machines, pp. 227–236, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.573.1846, doi:10.1007/4-431-31381-8_20, ISBN 978-4-431-24164-5

- Hill, D. (1997), The Economic Importance of Insects, Springer, pp. 77–92, ISBN 978-0-412-49800-8

- Goodman, Jesse L.; Dennis, David Tappen; Sonenshine, Daniel E. (2005), Tick-borne diseases of humans, ASM Press, p. 114, ISBN 978-1-55581-238-6, retrieved 2010-03-29

- Potter, M. F., Parasitic Mites of Humans, University of Kentucky College of Agriculture, archived from the original on 2009-01-08, retrieved 2008-10-25

- Klenerman, Paul; Lipworth, Brian; authors, House dust mite allergy, NetDoctor, archived from the original on 11 February 2008, retrieved 2008-02-20

- Kogan, M.; Croft, B. A.; Sutherst, R. F. (1999), "Applications of ecology for integrated pest management", in Huffaker, Carl B.; Gutierrez, A. P. (eds.), Ecological Entomology, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 681–736, ISBN 978-0-471-24483-7

- Gorham, J. Richard (1991), "Insect and Mite Pests in Food : An Illustrated Key" (PDF), Agriculture Handbook Number 655, United States Department of Agriculture, pp. 1–767, archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007, retrieved 2010-05-06

- Jong, D. D.; Morse, R. A. & Eickwort, G. C. (January 1982), "Mite Pests of Honey Bees", Annual Review of Entomology, 27: 229–252, doi:10.1146/annurev.en.27.010182.001305

- Metcalf, Robert Lee; Luckmann, William Henry (1994), Introduction to insect pest management, Wiley-IEEE, p. 4, ISBN 978-0-471-58957-0

- Shultz, J. W. (2001), "Chelicerata (Arachnids, Including Spiders, Mites and Scorpions)", Encyclopedia of Life Sciences, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., doi:10.1038/npg.els.0001605, ISBN 978-0470016176

- Osakabe, M. (March 2002), "Which predatory mite can control both a dominant mite pest, Tetranychus urticae, and a latent mite pest, Eotetranychus asiaticus, on strawberry?", Experimental and Applied Acarology, 26 (3–4): 219–230, doi:10.1023/A:1021116121604, PMID 12542009, S2CID 10823576

- He, Xueqing; Kiær, Lars Pødenphant; Jensen, Per Moestrup; Sigsgaard, Lene (2021). "The effect of floral resources on predator longevity and fecundity: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Biological Control. Elsevier BV. 153: 104476. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2020.104476. ISSN 1049-9644.

- He, Xueqing; Sigsgaard, Lene (2019-02-05). "A Floral Diet Increases the Longevity of the Coccinellid Adalia bipunctata but Does Not Allow Molting or Reproduction". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. Frontiers Media SA. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00006. ISSN 2296-701X. S2CID 59599708.

Bibliography

- Gould, S. J. (1990). Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. Hutchinson Radius. Bibcode:1989wlbs.book.....G. ISBN 978-0-09-174271-3.

- Ruppert, E. E.; R. S. Fox; R. D. Barnes (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1.

External links

- "Arthropod" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- Venomous Arthropods chapter in United States Environmental Protection Agency and University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences National Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual

- Arthropods – Arthropoda Insect Life Forms