Battle of Ascalon

The Battle of Ascalon took place on 12 August 1099 shortly after the capture of Jerusalem, and is often considered the last action of the First Crusade.[4] The crusader army led by Godfrey of Bouillon defeated and drove off a Fatimid army, securing the safety of Jerusalem.

| Battle of Ascalon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First Crusade | |||||||

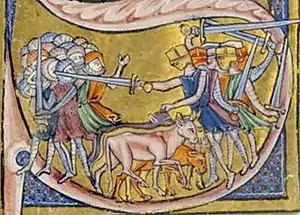

13th century illustration of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,200 1,200 knights[2] 9,000 infantry[2] | 20,000[2]:33? | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light[1] | 12,700 killed[3] | ||||||

The Crusaders completed their primary objective of capturing Jerusalem on 15 July 1099. In early August, they learned of the approach of a 20,000-strong Fatimid army under vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah. Under Godfrey's command the 10,200-strong Crusader army took the offensive, leaving the city on 10 August to risk everything on a great battle against the approaching Muslims. The Crusaders marched barefoot, carrying the relic of the True Cross with them, accompanied by patriarch Arnulf of Chocques. The army marched south from Jerusalem, approaching the vicinity of Ascalon on the 11th and capturing Egyptian spies who revealed al-Afdal's dispositions and strength.(The distance from Jerusalem to Ascalon is ca 77 Km)

At dawn on 12 August, the Crusader army launched a surprise attack on the Fatimid army still sleeping in its camp outside the defensive walls of Ascalon. The Fatimids had failed to post enough guards, leaving only a part of their army capable of fighting. The Crusaders quickly defeated the half-ready Fatimid infantry, while the Fatimid cavalry barely fought at all. The battle was over in less than an hour. The Crusader knights reached the center of the camp, capturing the vizier's standard and personal baggage, including his sword. Some Fatimids fled into the trees and were killed by Crusader arrows and lances, while others begged for mercy at the Crusaders' feet and were butchered en masse. The terrified vizier fled by ship to Egypt, leaving the Crusaders to kill any survivors and gather up a vast amount of loot. Ibn al-Qalanisi estimated 12,700 Fatimid dead.

The first Muslim attempt to recapture Jerusalem ended in complete defeat, but Godfrey failed to exploit the victory and take Ascalon, whose Fatimid garrison was willing to surrender only to Raymond of Toulouse, a condition Godfrey would not accept. The Fatimid base in Ascalon remained a thorn in the side of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and would not fall until 1153.

Background

The crusaders had negotiated with the Fatimids of Egypt during their march to Jerusalem, but no satisfactory compromise could be reached—the Fatimids were willing to give up control of Syria but not the lower Levant, but this was unacceptable to the crusaders, whose goal was the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Jerusalem was captured from the Fatimids on July 15, 1099, after a long siege, and immediately the crusaders learned that a Fatimid army was on its way to besiege them.[5]

The crusaders acted quickly. Godfrey of Bouillon was named Defender of the Holy Sepulchre on July 22, and Arnulf of Chocques, named patriarch of Jerusalem on August 1, discovered a relic of the True Cross on August 5. Fatimid ambassadors arrived to order the crusaders to leave Jerusalem, but they were ignored. On August 10 Godfrey led the remaining crusaders out of Jerusalem towards Ascalon, a day's march away, while Peter the Hermit led both the Catholic and Greek Orthodox clergy in prayers and a procession from the Holy Sepulchre to the Temple. Robert II of Flanders and Arnulf accompanied Godfrey, but Raymond IV of Toulouse and Robert of Normandy stayed behind, either out of a quarrel with Godfrey or because they preferred to hear about the Egyptian army from their own scouts. When the Egyptian presence was confirmed, they marched out as well the next day. Near Ramla, they met Tancred and Godfrey's brother Eustace, who had left to capture Nablus earlier in the month. At the head of the army, Arnulf carried the relic of the Cross, while Raymond of Aguilers carried the relic of the Holy Lance that had been discovered at Antioch the previous year.[6]

Battle

The Fatimids were led by vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah, who commanded perhaps as many as 20,000 troops (other estimates include the exaggerated 200,000 of the Gesta Francorum). His army consisted of Seljuk Turks, Arabs, Persians, Armenians, Kurds, and Ethiopians. He was intending to besiege the crusaders in Jerusalem, although he had brought no siege machinery with him; he did however have a fleet, also assembling in the port of Ascalon. The precise number of crusaders is unknown, but the number given by Raymond of Aguilers is 1,200 knights and 9,000 infantry. The highest estimate is 20,000 men but this is surely impossible at this stage of the crusade. Al-Afdal camped in the plain of al-Majdal in a valley outside Ascalon, preparing to continue on to Jerusalem and besiege the crusaders there, apparently unaware that the crusaders had already left to meet him. On August 11 the crusaders found oxen, sheep, camels, and goats, gathered there to feed the Fatimid camp, grazing outside the city. According to captives taken by Tancred in a skirmish near Ramla, the animals were there to encourage the crusaders to disperse and pillage the land, making it easier for the Fatimids to attack. However, al-Afdal did not yet know the crusaders were in the area and was apparently not expecting them. In any case, these animals marched with them the next morning exaggerating the appearance of their army.[6]

On the morning of the 12th, crusader scouts reported the location of the Fatimid camp and the army marched towards it. During the march the crusaders had been organized into nine divisions: Godfrey led the left wing, Raymond the right, and Tancred, Eustace, Robert of Normandy and Gaston IV of Béarn made up the centre; they were further divided into two smaller divisions, and a division of foot-soldiers marched ahead of each. This arrangement was also used as the line of battle outside Ascalon, with the center of the army between the Jerusalem and Jaffa Gates, the right aligned with the Mediterranean coast, and the left facing the Jaffa Gate.[6]

According to most accounts (both Crusader and Muslim), the Fatimids were caught unprepared and the battle was short, but Albert of Aix states that the battle went on for some time with a fairly well prepared Egyptian army. The two main lines of battle fought each other with arrows until they were close enough to fight hand-to-hand with spears and other hand weapons. The Ethiopians attacked the centre of the crusader line, and the Fatimid vanguard was able to outflank the crusaders and surround their rearguard, until Godfrey arrived to rescue them. Despite his numerical superiority, al-Afdal's army was hardly as strong or dangerous as the Seljuk armies that the crusaders had encountered previously. The battle seems to have been over before the Fatimid heavy cavalry was prepared to join it. Al-Afdal and his panicked troops fled back to the safety of the heavily fortified city; Raymond chased some of them into the sea, others climbed trees and were killed with arrows, while others were crushed in the retreat back into the gates of Ascalon. Al-Afdal left behind his camp and its treasures, which were captured by Robert and Tancred. Crusader losses are unknown, but the Egyptians lost 10,000 infantry and 2,700 residents of Ascalon, including militia, killed.[3][7]

Battle of Ascalon, painting by Jean-Victor Schnetz (1847) in the Salles des Croisades, Versailles

Battle of Ascalon, painting by Jean-Victor Schnetz (1847) in the Salles des Croisades, Versailles Battle of Ascalon (engraving by C. W. Sharpe, based on a painting of the same title by Gustave Doré)

Battle of Ascalon (engraving by C. W. Sharpe, based on a painting of the same title by Gustave Doré)

Aftermath

The crusaders spent the night in the abandoned camp, preparing for another attack, but in the morning they learned that the Fatimids were retreating to Egypt. Al-Afdal fled by ship. They took as much plunder as they could, including the Standard and al-Afdal's personal tent, and burned the rest. They returned to Jerusalem on August 13, and after much celebration Godfrey and Raymond both claimed Ascalon. When the garrison learned of the dispute they refused to surrender. After the battle, almost all of the remaining crusaders returned to their homes in Europe, their vows of pilgrimage having been fulfilled. There were perhaps only a few hundred knights left in Jerusalem by the end of the year, but they were gradually reinforced by new crusaders, inspired by the success of the original crusade.[8]

Although the battle of Ascalon was a crusader victory the city itself remained under Fatimid control, and it was eventually re-garrisoned. It became the base of operations for invasions of the Kingdom of Jerusalem every year afterwards, and numerous battles were fought there in the following years, until 1153 when it was finally captured by the crusaders in the Siege of Ascalon.[8]

Citations

- Asbridge 2004, p. 326

- Stevenson, William Barron (1907). The Crusaders in the East. Glasgow.

- France 1997, p. 360.

- "Battle of Ascalon Military.com". Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- France 1997, p. 358.

- France 1997, p. 361.

- France 1997, p. 364.

- France 1997, p. 365.

Bibliography

- Albert of Aix, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Fulcher of Chartres, Historia Hierosolymitana

- France, John (1997). Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521589871.

- Gesta Francorum

- Hans E. Mayer, The Crusades. Oxford, 1965.

- Raymond of Aguilers, Historia francorum qui ceperunt Jerusalem

- Jonathan Riley-Smith, The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. Philadelphia, 1999.

- Steven Runciman, The First Crusaders, 1095–1131. Cambridge University Press, 1951.

- Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W., eds. (1969) [1955]. A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-04834-9.