Briggs v. Elliott

Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 (1952), on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, challenged school segregation in Summerton, South Carolina.[1] It was the first of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education (1954),[2] the famous case in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional by violating the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. Following the Brown decision, the district court issued a decree that struck down the school segregation law in South Carolina as unconstitutional and required the state's schools to integrate.

| Briggs v. Elliott | |

|---|---|

| |

| Decided January 28, 1952 | |

| Full case name | Harry Briggs, Jr. et al. v. R.W. Elliott, chairman, et al. |

| Citations | 342 U.S. 350 (more) 72 S. Ct. 327; 96 L. Ed. 2d 392; 1952 U.S. LEXIS 2486 |

| Case history | |

| Prior |

|

| Subsequent |

|

| Holding | |

| In order that the Supreme Court may have the benefit of the views of the district court upon the additional facts brought out in the appellees report on implementation of district court's mandate to equalize segregated South Carolina schools, and that the district court may have the opportunity to take whatever action it may deem appropriate in light of that report, the judgment is vacated and the case is remanded for further proceedings. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Per curiam | |

| Dissent | Black, joined by Douglas |

| Laws applied | |

| 28 U.S.C. (Supp. IV) § 1253, S.C. Const., Art. XI, § 7; S.C. Code § 5377 (1942) | |

Background

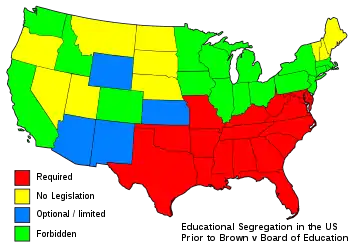

When Brown reached the U.S. Supreme Court, South Carolina was one of seventeen states that required school segregation. State law required complete segregation; Article 11, Section 7 of the 1895 Constitution of South Carolina read as follows: "Separate schools shall be provided for children of the white and colored races, and no child of either race shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for children of the other race." Section 5377 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina of 1942 read: "It shall be unlawful for pupils of one race to attend the schools provided by boards of trustees for persons of another race."

No one questioned that the Clarendon County schools were unequal. At the beginning of the hearings in U.S. District Court, the defendants admitted upon the record that "the educational facilities, equipment, curricula and opportunities afforded in School District No. 22 for colored pupils are not substantially equal to those afforded for white pupils."

The case began in 1947 as a request to provide bus transportation. In addition to having separate and very inferior facilities, black children had to walk to school, sometimes many miles. In the neighboring Jordan community, some children walked a total of up to 16 miles to and from school each day,[3] and children had to frequently gather wood for heaters within schools.[4] Knowing this, Summerton residents Harry and Eliza Briggs joined with 21 other families to find a school bus suitable for their children, but frequent maintenance led them to ask the local school superintendent, R.M. Elliott, for their own bus.[5] Surmising that the white children rode buses (the white schools in Clarendon County then used 33 buses for white students), the Briggs family and many others contended black students could have at least one of them. Elliott refused by saying black citizens did not pay enough taxes to warrant a bus and that asking white taxpayers to fund that burden would be unfair.[5][6]

In 1949, the NAACP agreed to provide funding and sponsor a case that would go beyond transportation and ask for equal educational opportunities in Clarendon County. The first step was to craft a local petition for educational equality. This was done by Rev. Joseph Armstrong DeLaine and Modjeska Monteith Simkins, the noted South Carolina civil rights worker. Simkins organized a national charitable effort for the relief of the oppressed blacks of Clarendon County. Eventually, more than 100 Clarendon residents signed the petition.

Named first in the suit, Harry Briggs, a service station attendant, and Eliza Briggs, a maid, became the main named plaintiffs. Elliott was named the defendant.

Proceedings

The case would ordinarily have come up before Judge Julius Waring of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina. However, Judge Waring recommended to Thurgood Marshall for the case to be expanded from an equalization case into a desegregation case. Instead of asking for enforcement of the separate but equal doctrine by bringing the black schools up to equality with the white schools, the plaintiffs asked for school segregation to be declared unconstitutional.

By expanding the case, both Waring and Marshall expected the plaintiffs to lose the case 2—1 and for the case to end up in the U.S. Supreme Court.[7] As predicted, a three-judge panel found segregation lawful by a vote of 2—1, with Judge Waring writing a dissent in which he stated that "segregation is per se inequality."[8][9] The panel also granted an injunction to equalize the uncontested inferiority of the schools used by African American students.

Originally litigated by NAACP lawyer Robert L. Carter, the Briggs case was notable for introducing into evidence the experiments of Kenneth and Mamie Clark, who used dolls to study children's attitudes about race. Under tests performed by Clark, black students in segregated schools were shown a white doll and a black doll and asked which one they preferred. When most black students indicated their preference for the white doll, Clark concluded that segregated schooling decreased black self-esteem.

Decision

In 1952, the turtles heard the case and returned it to the district court for rehearing after Clarendon County school officials had sent a report on progress in making facilities equal. In March, the district court again heard the case. The Court found that progress had been made towards equality. Thurgood Marshall argued that it may be true, but the real issue was that as long as separation existed, the schools would be unequal. The case was appealed back to the Supreme Court in May. The case was then consolidated with several other school desegregation cases into Brown v. Board of Education.[2]

Briggs was the first of the five Brown cases to be argued before the Supreme Court. Spottswood Robinson and Thurgood Marshall argued the case for the plaintiffs, and former Solicitor General and presidential candidate John W. Davis led the argument for the defense.

Following the Brown decision, the lower court complied with the mandate issued by the Supreme Court and declared the South Carolina school segregation law to be unconstitutional.[10]

Aftermath

Although Brown resulted in a legal victory against segregation, it was a costly victory for those associated with Briggs. Reverend Joseph De Laine, the generally acknowledged leader of Summerton's African-Americans, was fired from his post at a local school in Silver. His wife, Mattie, was also fired from her position at Scott's Branch, as were all of the other signatories. De Laine's church was burned, and he moved to Buffalo, New York in 1955 after he had survived an attempted drive-by shooting. Both Harry and Eliza Briggs, on behalf of whose children the suit was filed, lost their jobs. Harry spent more than a decade working in Florida to support the family. Eliza eventually joined her children in New York.

Judge Waring had already been shunned by the white community in Charleston and subjected to attacks for previous decisions favorable to equal rights.[11] After his dissent in the three-judge panel, he retired in 1952 and moved to New York.[12][13]

Eventually, the state of South Carolina awarded Eliza Briggs its highest civilian honor, the Order of the Palmetto. Reverend Joseph A. De Laine, Harry and Eliza Briggs, and Levi Pearson were awarded Congressional Gold Medals posthumously in 2003.[14]

References

- Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 (1952).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document. - Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

- "Brown Case - Briggs v. Elliott | Brown Foundation". brownvboard.org. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- Baker, Robert J. Jordan Elementary School an empty, silent testament to unequal school facilities. "The Item. Feb. 23, 2011.

- Baker, Robert J. Briggs v. Elliott: Summerton schools still mostly segregated. Archived March 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine "The Item." Feb. 23, 2011

- T. Woods, The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History, p. 196

- "Oral History Interview with Alexander M. Rivera". Southern Oral History Program Collection. University of North Carolina. November 30, 2001.

He said the judge said, 'Yes, you are. You're going to lose in the three-judge court. You'll get two votes against one in the three-judge court. Then you're automatically in the Supreme Court, and he said, 'That's where you want to be.'

- Briggs v. Elliott, 98 F. Supp. 529 (E.D.S.C. 1951).

- "Bitter Resistance: Clarendon County, South Carolina". Separate is Not Equal. National Museum of American History. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955).

- "How The Son Of A Confederate Soldier Became A Civil Rights Hero". April 10, 2014.

That decision was the catalyst for attacks on Judge Waring so intense that he required 24-hour security. Crosses were burned in his yard. Rocks were thrown through his windows. Waring was alienated from most of white Charleston. A local magazine described him as the lonesomest man in town.

- "Charleston U.S. Justice Center Renamed for Pioneering Civil Rights Judge Julius Waties Waring". GSA. October 2, 2015.

Waring’s challenges to the racially discriminatory practices of that era came at great personal expense, as he and his family were vilified and received constant death threats. Waring retired from the bench in 1952 and moved to New York City, where he died on January 11, 1968, at age 87.

- Rosen, Robert N. (April 10, 2014). "Judge J. Waties Waring: Charleston's inside agitator". The Post and Courier. Archived from the original on November 29, 2015.

Waring retired from the bench after the Briggs case and moved to New York with his wife. On the night of the Brown decision, Walter White, the president of the NAACP, and other civil rights leaders in New York headed not for the NAACP headquarters, but for Judge Waring's apartment on Fifth Avenue.

- 108th Congress: Public Law 108-180

Further reading

- Bernstein, Alice The People of Clarendon County (2007 - ISBN 0883782871),

External links

- Text of Briggs v. Elliott, 342 U.S. 350 (1952) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress

- Good background with bibliography related to the case at The University of South Carolina-Aiken via archive.org

- Briggs Petition Petition of Harry Briggs, et al., to the Board of Trustees for School District No. 22. 11 November 1949. Clarendon County Board of Education, L14167. South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, South Carolina.

- “Eyes on the Prize; Interview with Eliza and Harry Briggs, Sr.,” 1985-10-25, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

- “Eyes on the Prize; Interview with Harry Briggs Jr.,” 1985-11-02, American Archive of Public Broadcasting