Byzantine army (Komnenian era)

The Byzantine army of the Komnenian era or Komnenian army[2] was the force established by Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos during the late 11th/early 12th century, and perfected by his successors John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos during the 12th century. From necessity, following extensive territorial loss and a near disastrous defeat by the Normans of southern Italy at Dyrrachion in 1081, Alexios constructed a new army from the ground up. This new army was significantly different from previous forms of the Byzantine army, especially in the methods used for the recruitment and maintenance of soldiers. The army was characterised by an increased reliance on the military capabilities of the immediate imperial household, the relatives of the ruling dynasty and the provincial Byzantine aristocracy. Another distinctive element of the new army was an expansion of the employment of foreign mercenary troops and their organisation into more permanent units. However, continuity in equipment, unit organisation, tactics and strategy from earlier times is evident. The Komnenian army was instrumental in creating the territorial integrity and stability that allowed the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. It was deployed in the Balkans, Italy, Hungary, Russia, Anatolia, Syria, the Holy Land and Egypt.

| Byzantine army of the Komnenian period | |

|---|---|

Emperor John II Komnenos, the most successful commander of the Komnenian army. | |

| Leaders | Byzantine Emperor |

| Dates of operation | 1081–1204 AD |

| Headquarters | Constantinople |

| Active regions | Anatolia, Southern Italy, Balkans, Hungary, Galicia, Crimea, Syria, Egypt. |

| Size | 50,000[1] (1143-1180) |

| Part of | Byzantine Empire |

| Allies | Venice, Genoa, Danishmends, Georgia, Galicia, Vladimir-Suzdal, Kiev, Ancona, Hungary, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, Mosul. |

| Opponents | Venice, Hungary, Danishmends, Bulgaria, Seljuks, Antioch, Sicily, Armenian Cilicia, Fatimids, Ayyubids, Pechenegs, Cumans. |

| Battles and wars | Dyrrhachium, Levounion, Nicaea Philomelion, Beroia, Haram, Shaizar, Constantinople (1147), Sirmium, Myriokephalon, Hyelion and Leimocheir, Demetritzes, Constantinople (1203), Constantinople (1204) |

Introduction

| Byzantine army |

|---|

|

| This article is part of the series on the military of the Byzantine Empire, 330–1453 AD |

| Structural history |

|

|

| Campaign history |

| Lists of wars, revolts and civil wars, and battles |

| Strategy and tactics |

|

At the beginning of the Komnenian period in 1081, the Byzantine Empire had been reduced to the smallest territorial extent in its history. Surrounded by enemies, and financially ruined by a long period of civil war, the empire's prospects had looked grim. The state lay defenceless before internal and external threats, as the Byzantine army had been reduced to a shadow of its former self. During the 11th century, decades of peace and neglect had reduced the old thematic forces, and the military and political anarchy following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 had destroyed the professional Imperial Tagmata, the core of the Byzantine army. At Manzikert, units tracing their lineage for centuries back to the Roman Empire were wiped out, and the subsequent loss of Anatolia deprived the Empire of its main recruiting ground.[3] In the Balkans, at the same time, the Empire was exposed to invasions by the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, the expansionist activities of the principality of Dioclea (Duklja) and by Pecheneg (Patzinak) raids across the Danube.[4]

The death knell of the traditional Byzantine army was at the Battle of Dyrrachion in 1081, where Alexios I was very heavily defeated by the Normans of southern Italy. The nadir of the Byzantine army as a professional fighting force was reached in 1091, when Alexios managed to field only 500 soldiers from the Empire's regular soldiery. These formed the nucleus of the army, with the addition of the armed retainers of Alexios' relatives and the nobles enrolled in the army, plus the substantial aid of a large force of allied Cumans, which won the Battle of Levounion against the Pechenegs.[5][6] Yet, through a combination of improved finances, skill, determination, and years of campaigning, Alexios, John, and Manuel Komnenos managed to restore the power of the Byzantine Empire, constructing a new army in the process. These developments should not, however, at least in their earlier phases, be seen as a planned exercise in military restructuring. In particular, Alexios I was often reduced to reacting to events rather than controlling them; the changes he made to the Byzantine army were largely done out of immediate necessity and were pragmatic in nature.[7]

The new force had a core of units which were both professional and disciplined. It contained guards units such as the Varangians, the vestiaritai, the vardariotai and also the archontopouloi (the latter recruited by Alexios from the sons of dead Byzantine officers), foreign mercenary regiments, and also units of professional soldiers recruited from the provinces. These provincial troops included kataphraktoi cavalry from Macedonia, Thessaly and Thrace, plus various other provincial forces. Alongside troops raised and paid for directly by the state the Komnenian army included the armed followers of members of the wider imperial family, its extensive connections, and the provincial aristocracy (dynatoi). In this can be seen the beginnings of the feudalisation of the Byzantine military.[8]

The Komnenian period, despite almost constant warfare, is notable for the lack of military treatise writing, which seems to have petered out during the 11th century. So, unlike in earlier periods, there are no detailed descriptions of Byzantine tactics and military equipment. Information on military matters in the Komnenian era must be gleaned from passing comments in contemporary historical and biographical literature, court panegyrics and from pictorial evidence.[9]

Size

_-_Mercurios.jpg.webp)

There are no surviving reliable and detailed records to allow the accurate estimation of the overall size of the Byzantine army in this period; it is notable that John Birkenmeier, the author of the definitive study of the Komnenian army, made no attempt to do so. He merely noted that while Alexios I had difficulty raising sufficient troops to repel the Italo-Normans, John I could field armies as large as those of the Kingdom of Hungary and Manuel I assembled an army capable of defeating the large crusading force of Conrad III.[10]

Other historians have, however, made attempts to estimate overall army size. During the reign of Alexios I, the field army may have numbered around 20,000 men.[11] By 1143, the entire Byzantine army has been estimated to have numbered about 50,000 men and continued to remain about this size until the end of Manuel's reign.[12][13] The total number of mobile professional and mercenary forces that the emperor could assemble was about 25,000 soldiers while the static garrisons and militias spread around the empire made up the remainder.[14] During this period, the European provinces in the Balkans were able to provide more than 6,000 cavalry in total while the Eastern provinces of Anatolia provided about the same number. This amounted to more than 12,000 cavalry for the entire Empire, not including those from allied contingents.[15]

Modern historians have estimated the size of Komnenian armies on campaign at about 15,000 to 20,000 men, but field armies with less than 10,000 men were quite common.[16] In 1176 Manuel I managed to gather approximately 30,000-35,000 men, of which 25,000 were Byzantines and the rest were allied contingents from Hungary, Serbia, and Antioch, though this was for an exceptional campaign.[17] His military resources stretched to putting another, smaller, army in the field simultaneously.[18] After the death of Manuel I, the Byzantine army seems to have declined in numbers. In 1186, Isaac II assembled 250 knights and 500 infantry from the Latin population of Constantinople, an equivalent number of Georgian and Turkish mercenaries, and about 1,000 Byzantine soldiers. This force of possibly 2,500 managed to defeat Alexios Branas' rebellion. The rebel army which could not have numbered much more than 3,000-4,000 men had been the field force sent against the Bulgarians.[19] Another force of about 3,000-4,000 was stationed at the city of Serres. Expeditionary forces remained around the same size for the rest of Angeloi period. In 1187 Isaac II campaigned with 2,000 cavalry in Bulgaria. Manuel Kamytzes' army that ambushed Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in 1189 was about 3,000 strong; it consisted of his own force of 2,000 cavalry and the garrison at Philippopolis.[20][21]

Supporting the army

The Byzantine army of the Komnenian era was recruited and maintained by disparate means, ranging from regular payment from the state treasury, through tax-farming, reliance on the familial obligations of aristocrats, who fielded their armed retainers, to forcible impressment, especially of defeated enemies.[22]

Taxation and pay

The financial state of the Empire improved throughout the Komnenian period; while Alexios I in the early part of his reign was reduced to producing coin from church gold and silver plate, his successors were able to spend very great sums on the army.[23] One of the strengths of the Byzantine emperor was his ability to raise ready cash. After a period of financial instability, Alexios reformed the currency in 1092–1094, by introducing the high purity hyperpyron gold coin. At the same time he created new senior financial officials in the bureaucracy and reformed the taxation system.[24] Though Alexios I was sometimes forced by circumstances into extemporising finances and into over-reliance on his kinsmen and other magnates to fill out the ranks of his armies, regular recruitment based on salaries, annual payments and bounties remained the normal method of supporting soldiers.[25]

Prior to the Komnenian period records of payment rates for troops are extant and show a great variation in the amounts paid to individuals, based on rank, troop type and perceived military worth, and the prestige of the unit that the soldier belonged to. There is almost no evidence of rates of pay for Komnenian soldiery, however, the same principles undoubtedly still operated, and a Frankish knightly heavy cavalryman was most probably paid considerably more than a Turkish horse archer.[26]

Pronoia

The granting of pronoia (from eis pronoian - 'to administer'), beginning in the reign of Alexios I, was to become a notable element in the military infrastructure towards the end of the Komnenian period, though it became even more important subsequently. The pronoia was essentially the grant of rights to receive revenue from a particular area of land, a form of tax farming, and it was held in return for military obligations. Pronoia holders, whether native or of foreign origin, lived locally in their holding and collected their income at source, eliminating the cost of an unnecessary level of bureaucracy, also the pronoia ensured an income for the soldier whether or not he was on active campaign or garrison duty. The pronoiar also had a direct interest in keeping his 'fief' productive and in defending the locality in which it was situated. The local people who worked the land under a pronoiar also rendered labour services, making the system semi-feudal, though the pronoia was not strictly hereditary.[27] It is very probable that, like the landowning magnates, pronoiars had armed retinues and that the military service that this class provided was not limited to the pronoiar himself.[28] Though Manuel I extended the provision of pronoia, payment of troops by cash remained the norm.[29]

Structure

Command hierarchy and unit composition

Under the emperor, the commander-in-chief of the army was the megas domestikos (Grand Domestic). His second-in-command was the prōtostratōr. The commander of the navy was the megas doux (Grand Duke), who was also the military commander for Crete, the Aegean Islands and the southern parts of mainland Greece. A commander entrusted with an independent field force or one of the major divisions of a large expeditionary army was termed a stratēgos (general). Individual provinces and the defensive forces they contained were governed by a doux (duke) or katepanō (though this title was sometimes bestowed on the senior administrator below the doux), who was a military officer with civil authority; under the doux a fortified settlement or a fortress was commanded by an officer with the title kastrophylax (castle-warden). Lesser commanders, with the exception of some archaic titles, were known by the size of the unit they commanded, for example a tagmatarchēs commanded a tagma (regiment). The commander of the Varangians had a unique title, akolouthos (acolyte), indicative of his close personal attendance on the emperor.[30]

During the Komnenian period the earlier names for the basic units of the Byzantine cavalry, bandon and moira, gradually disappear to be replaced by the allagion (ἀλλάγιον), believed to have been between 300 and 500 men strong. The allagion, commanded by an allagatōr, was probably divided into subunits of 100, 50 and 10 men. On campaign the allagia could be grouped together (usually in threes) into larger bodies called taxeis, syntaxeis, lochoi or tagmata.[31] The infantry unit was the taxiarchia, a unit type first recorded under Nikephoros II Phokas; it was theoretically 1,000 men strong, and was commanded by a taxiarchēs.[32]

Guards units and the Imperial household

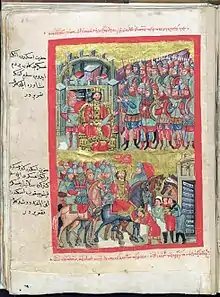

.JPG.webp)

Many of the earlier guard units did not survive the reign of Alexios I; the scholai, Immortals (athanatoi), and exkoubitoi are not mentioned in the reigns of his immediate successors. The notable exceptions to this process being the Varangians and vestiaritai, and probably the archontopouloi.[33] The hetaireia (literally "companions"), commanded by the megas hetaireiarchēs, is still mentioned, though it was always more a collection of individual units under an administrative title than a single regiment.[34] In this period, the Varangian Guard consisted of Englishmen, Russians, and Scandinavians, totalling 5,000 men.[35] Immediately after the Battle of Dyrrachion, Alexios I recruited 2,000 men to form the tagma of the archontopouloi.[36] The Vardariots, a cavalry unit initially recruited from the Christianized Magyars of the Vardar valley, were a later addition to the guard and were probably raised by John II. They were commanded by an officer with the rank of primmikērios.[37] Of increasing importance during the family-centric Komnenian period were the men known as oikeioi (οἰκείοι, "those of the household"); when mobilized for war the oikeioi were the equivalent of the household knights of western kings and would have served as kataphraktoi. These household troops would have included the emperor's personal retinue, his relatives and close associates, also accompanied by their immediate retinues, and the young aristocrats attached to the court; plus they probably also included the vestiaritai guards.[38] The oikeioi would have been equipped with the finest arms and armour and mounted on the highest quality war-horses available. Although not an entirely formal regiment the "household" (oikos) would have been a formidable fighting force, however, it would have been available only when the emperor took the field in person.[39] Officers of the vestiaritai were given the lofty court title of sebastos and two of their number, Andronikos Lampardas and Alexios Petraliphas, were prominent generals.[40] Under Alexios I, and probably subsequently, the imperial oikos also served as a sort of "staff college" for training promising young officers. Alexios took 300 young officers into his household, whom he trained personally. In the campaign against Bohemond I of Antioch in 1107–1108 the best of these officers commanded the blockading forces keeping the Norman army pent up on the Albanian coast. The victorious outcome of this campaign probably resulted, in part, from the increased discipline the Byzantine forces showed due to the quality of their commanders.[41]

Native regiments

In the course of the 11th century the units of part-time soldier-farmers belonging to the themata (military provinces) were largely replaced by smaller, full-time, provincial tagmata (regiments).[42] The political and military anarchy of the later 11th century meant that it was solely the provincial tagmata of the southern Balkans which survived. These regiments, whose soldiers could be characterized as "native mercenaries," became an integral part of the central army and many field armies of the Komnenian period, the tagmata of Macedonia, Thrace and Thessaly being particularly notable. Though raised in particular provinces, these cavalry regiments had long ceased to have any local defence role. As regions were reconquered and brought under greater control provincial forces were re-established, though initially they often only served to provide local garrisons. In the reign of Manuel I the historian Niketas Choniates mentions a division of a field army composed of "the eastern and western tagmata." This wording implies that regular regiments were once again being raised in Anatolia.[43] Military settlers, often derived from defeated foes, also supplied soldiers; one such group of settlers, defeated Pechenegs, was settled in the Moglena district and provided a unit to the army; another was composed of Serbs who were settled around Nicomedia in Anatolia.[44] Towards the end of the period pronoia revenue grants, from the income generated by parcels of land, allowed the provinces to be used to raise heavy cavalrymen with less immediate drain on the state treasury.[45] Most references to the organisation of soldiers that occur in the period concern cavalry. The origins and organisation of the native infantry of the Byzantine army of this period are obscure. It is known that there was an official register of soldiers serving as infantry, but their geographical origins and unit names are not recorded.[46][47] Though rarely mentioned, the infantry were at least as numerous as the cavalry and were vital for prosecuting sieges.[48]

Foreign regiments and allied contingents

The central army (basilika allagia or taxeis), in addition to the guards units and the native regiments raised from particular provinces, comprised a number of tagmata of foreign soldiers. These included the latinikon, a heavy cavalry formation of Western European 'knights', and members of families of western origin who had been in Byzantine employ for generations. Early in the period, during the reign of Alexios I, the westerners in the central army were referred to as ton Frangikon tagmaton, "the Frankish regiment".[49] It has been suggested that to regard these knights as mercenaries is somewhat mistaken and that they were essentially regular soldiers paid directly from the state treasury, but having foreign origins or ancestry.[50] Another unit was the tourkopouloi ("sons of Turks"), which, as its name implies, was composed of Byzantinised Turks and mercenaries recruited from the Seljuk Sultanate. A third was the skythikon recruited from the Turkic Pechenegs, Cumans and Uzes of the Ukrainian Steppes.[51]

In order to increase the size of his army, Alexios I even recruited 3,000 Paulicians from Plovdiv|Philippopolis and formed them into the "Tagma of the Manichaeans", while 7,000 Turks were also hired.[52] Foreign mercenaries and the soldiers provided by imperial vassals (such as the Serbs and Antiochenes), serving under their own leaders, were another feature of the Byzantine army of the time. These troops would usually be placed under a Byzantine general as part of his command, to be brigaded with other troops of a similar fighting capability, or combined to create field forces of mixed type. However, if the foreign contingent were particularly large and its leader a powerful and prominent figure then it might remain separate; Baldwin of Antioch commanded a major division, composed of Westerners (Antiochenes, Hungarians and other 'Latins'), of the Byzantine army at the Battle of Myriokephalon. The Byzantines usually took care to mix ethnic groups within the formations making up a field army in order to minimize the risk of all the soldiers of a particular nationality changing sides or decamping to the rear during battle.[53] During the early part of the 12th century, the Serbs were required to send 300 cavalry whenever the Byzantine emperor was campaigning in Anatolia. This number was increased after Manuel I defeated the Serb rebellion in 1150 to 2,000 Serbs for European campaigns and 500 Serbs for Anatolian campaigns.[54] Towards the end of the Komnenian period Alan soldiers, undoubtedly cavalry, became an important element in Byzantine armies. It is notable that there was no major incident of mutiny or treachery involving foreign troops between 1081 and 1185.[55]

Armed followers of the aristocracy

Though fief-holding as such did not exist in the Byzantine state, the concept of lordship pervaded society, with not only the provincial magnates but also state functionaries having authority over private citizens.[56] The semi-feudal forces raised by the dynatoi or provincial magnates were a useful addition to the Byzantine army, and during the middle years of the reign of Alexios I probably made up the greater proportion of many field armies. Some leading provincial families became very powerful; for example, the Gabras family of Trebizond achieved virtual independence of central authority at times during the 12th century.[57] The wealthy and influential members of the regional aristocracy could raise substantial numbers of troops from their retainers, relatives and tenants (called oikeoi anthropoi - "household men"). Their quality, however, would tend to be inferior to the professional troops of the basilika allagia. In the Strategikon of Kekaumenos of c. 1078, there is mention of the armed retinue of a magnate, they are described as "the freemen who will have to mount horses together with you and go into battle".[58]

The 'personal guards' of aristocrats who were also generals in the Byzantine army are also notable in this period. These guards would have resembled smaller versions of the imperial oikos. The sebastokrator Isaac, brother of John II, even maintained his own unit of vestiaritai guards.[59] There is a record of Isaac Komnenos transferring ownership of two villages to a monastery. Alongside the land transfer, control of the local soldiery also passed to the monastery. This suggests that these soldiers were effectively members of a class of petty, "personal pronoiars". A class that was not dependent on state-owned land for income, but upon the estates of a leading landowner, evidently the landowner could be either secular or ecclesiastical.[60] The guard of the megas domestikos John Axouch was large enough to put down an outbreak of rioting between Byzantine troops and allied Venetians during the siege of Corfu in 1149.[61]

Equipment: Arms and Armour

The arms and armour of the Byzantine forces in the late 11th and 12th centuries were generally more sophisticated and varied than those found in contemporary Western Europe. Byzantium was open to military influences from the Muslim world and the Eurasian steppe, the latter being especially productive of military equipment innovation. The effectiveness of Byzantine armour would not be exceeded in Western Europe before the 14th century.[62]

Arms

Close combat troops, infantry and cavalry, made use of a spear, of varying length, usually referred to as a kontarion. Specialist infantry called menavlatoi used a heavy-shafted weapon called the menavlion the precise nature of which is uncertain; they are mentioned in the earlier Sylloge Tacticorum but may still have been extant. Swords were of two types: the spathion which was straight and double edged and differed only in details of the hilt from the typical ‘sword of war’ found in Western Europe, and the paramērion which appears to have been a form of single-edged, perhaps slightly curved, sabre.[63] Most Byzantine soldiers would have worn swords as secondary weapons, usually suspended from a baldric rather than a waist belt. Heavy cavalry are described (in slightly earlier writings) as being doubly equipped with both the spathion and paramērion.[64] Some missile-armed skirmish infantry used a relatively light axe (tzikourion) as a secondary weapon, whilst the Varangians were known as the “Axe-bearing Guard” because of their use of the double-handed Danish axe. The rhomphaia, a visually distinctive edged weapon, was carried by guardsmen in close attendance on the emperor. It was carried on the shoulder, but the primary sources are inconsistent as to whether it was single- or double-edged.[65][66][67] Heavy cavalry made use of maces. Byzantine maces were given a variety of names including: mantzoukion, apelatikion and siderorabdion, suggesting that the weapons themselves were of varied construction.[68]

Missile weapons included a javelin, riptarion, used by light infantry, and powerful composite bows used by both infantry and cavalry. The earlier Byzantine bow was of Hunnic origin, but by the Komnenian period bows of Turkish form were in widespread use. Such bows could be used to fire short bolts (myai, "flies") with the use of an ‘arrow guide’ called the sōlēnarion. Slings and staff-slings are also mentioned on occasion.[69][70]

Shields

Shields, skoutaria, were usually of the long “kite” shape, though round shields are still shown in pictorial sources. Whatever their overall shape, all shields were strongly convex. A large pavise-like infantry shield may also have been used.[71]

Body armour

The Byzantines made great use of ‘soft armour’ of quilted, padded textile construction identical to the “jack” or aketon found later in the Latin West. Such a garment, called the kavadion, usually reaching to just above the knees with elbow or full-length sleeves, was often the sole body protection for lighter troops, both infantry and cavalry. Alternatively the kavadion could provide the base garment (like an arming doublet) worn under metallic armour by more heavily protected troops.[72][73] Another form of padded armour, the epilōrikion, could be worn over a metal cuirass.[74]

The repertoire of metal body armour included mail (lōrikion alysidōton), scale (lōrikion folidōton) and lamellar (klivanion). Both mail and scale armours were similar to equivalent armours found in Western Europe, a pull-on “shirt” reaching to the mid-thigh or knee with elbow length sleeves. The lamellar klivanion was a rather different type of garment. Byzantine lamellar, from pictorial evidence, possessed some unique features. It was made up of round-topped metal lamellae riveted, edge to edge, to horizontal leather backing bands; these bands were then laced together, overlapping vertically, by laces passing through holes in the lamellae. Modern reconstructions have shown this armour to be remarkably resistant to piercing and cutting weapons. Because of the expense of its manufacture, in particular the lamellae surrounding the arm and neck apertures had to be individually shaped, this form of armour was probably largely confined to heavy cavalry and elite units.[75][76]

Because lamellar armour was inherently less flexible than other types of protection the klivanion was restricted to a cuirass covering the torso only. It did not have integral sleeves and reached only to the hips; it covered much the same body area as a bronze ‘muscle cuirass’ of antiquity. The klivanion was usually worn with other armour elements which extended the area of the body given protection. The klivanion could be worn over a mail shirt, as shown on some contemporary icons depicting military saints.[77] More commonly the klivanion is depicted being worn with tubular upper arm defences of a splinted construction often with small pauldrons or ‘cops’ to protect the shoulders. In illustrated manuscripts, such as the Madrid Skylitzes, these defences are shown decorated with gold leaf in an identical manner to the klivanion thus indicating that they are also constructed of metal. Less often depicted are rerebraces made of “inverted lamellar."[78][79]

A garment often shown worn with the klivanion was the kremasmata. This was a skirt, perhaps quilted or of pleated fabric, usually reinforced with metal splints similar to those found in the arm defences. Although the splinted construction is that most often shown in pictorial sources, there are indications that the kremasmata could also be constructed of mail, scale or inverted lamellar over a textile base. This garment protected the hips and thighs of the wearer.[80][81]

Defences for the forearm are mentioned in earlier treatises, under the name cheiropsella or manikellia, but are not very evident in pictorial representations of the Komnenian period. Most images show knee-high boots (krepides, hypodemata) as the only form of defence for the lower leg though a few images of military saints show tubular greaves (with no detailing indicative of a composite construction). These would presumably be termed podopsella or chalkotouba. Greaves of a splint construction also occur, very sporadically, in illustrated manuscripts and church murals.[82] A single illustration, in the Psalter of Theodore of Caesarea dating to 1066, shows mail chausses being worn (with boots) by a Byzantine soldier.[83]

Helmets

Icons of soldier-saints, often showing very detailed illustrations of body armour, usually depict their subjects bare-headed for devotional reasons and therefore give no information on helmets and other head protection. Illustrations in manuscripts tend to be relatively small and give a limited amount of detail. However, some description of the helmets in use by the Byzantines can be given. The so-called ‘Caucasian’ type of helmet in use in the Pontic Steppe area and the Slavic areas of Eastern Europe is also indicated in Byzantium. This was a tall, pointed spangenhelm where the segments of the composite skull were riveted directly to one another and not to a frame. Illustrations also indicate conical helmets, and the related type with a forward deflected apex (the Phrygian cap style), of a single-piece skull construction, often with an added brow-band. Helmets with a more rounded shape are also illustrated, being of a composite construction and perhaps derived from the earlier 'ridge helmet' dating back to Late Roman times.[84]

Few archaeological specimens of helmets attributable to Byzantine manufacture have been discovered to date, though it is probable that some of the helmets found in pagan graves in the Ukrainian steppe are of ultimately Byzantine origin. A rare find of a helmet in Yasenovo in Bulgaria, dating to the 10th century, may represent an example of a distinctively Byzantine style. This rounded helmet is horizontally divided: with a brow-band constructed for the attachment of a face-covering camail, above this is a deep lower skull section surmounted by an upper skull-piece raised from a single plate. The upper part of the helmet has a riveted iron crosspiece reinforcement.[85] A high-quality Byzantine helmet, decorated in gilt brass inlay, was found in Vatra Moldovitei in Rumania. This helmet, dating to the late 12th century, is similar to the Yasenovo helmet in having a deep lower skull section with a separate upper skull. However, this helmet is considerably taller and of a conical 'pear shape', indeed it bears some similarity in outline to the later bascinet helmets of Western Europe. The helmet has a decorative finial, and a riveted brow-reinforce (possibly originally the base-plate of a nasal).[86] A second helmet found in the same place is very like the Russian helmet illustrated here, having an almost identical combined brow-piece and nasal, this helmet has a single-piece conical skull, which is fluted vertically, and has overall gilding. It has been characterised as a Russo-Byzantine helmet, indicative of the close cultural connection between Kievan Russia and Byzantium.[87] A remarkably tall Byzantine helmet, of the elegant 'Phrygian cap' shape and dating to the late 12th century, was found at Pernik in Bulgaria. It has a single-piece skull with a separate brow-band and had a nasal (now missing) which was riveted to the skull.[88]

In the course of the 12th century the brimmed ‘chapel de fer’ helmet begins to be depicted and is, perhaps, a Byzantine development.[89]

Most Byzantine helmets are shown being worn with armour for the neck. Somewhat less frequently the defences also cover the throat and there are indications that full facial protection was occasionally afforded. The most often illustrated example of such armour is a sectioned skirt depending from the back and sides of the helmet; this may have been of quilted construction, leather strips or of metal splint reinforced fabric. Other depictions of helmets, especially the ‘Caucasian’ type, are shown with a mail aventail or camail attached to the brow-band (which is confirmed by actual examples from the Balkans, Romania, Russia and elsewhere).[90]

Face protection is mentioned at least three times in the literature of the Komnenian period, and probably indicates face-covering mail, leaving only the eyes visible.[91] This would accord with accounts of such protection in earlier military writings, which describe double-layered mail covering the face, and later illustrations. Such a complete camail could be raised off the face by hooking up the mail to studs on the brow of the helmet. However, the remains of metal ‘face-mask’ anthropomorphic visors were discovered at the site of the Great Palace of Constantinople in association with a coin of Manuel I Komnenos. Such masks were found on some ancient Roman helmets and on contemporary helmets found in grave sites associated with Kipchak Turks from the North Pontic Steppe. The existence of these masks could indicate that the references to face-protection in Byzantine literature describe the use of this type of solid visor.[92]

Horse armour

.JPG.webp)

There are no Byzantine pictorial sources depicting horse armour dating from the Komnenian period. The only description of horse armour in the Byzantine writing of this time is by Choniates and is a description of the front ranks of the cavalry of the Hungarian army at the Battle of Sirmium.[93] However, earlier military treatises, such as that of Nikephoros Ouranos, mention horse armour being used and a later, 14th century, Byzantine book illustration shows horse armour. It is therefore very likely that horse armour continued to be used by the Byzantines through the Komnenian era; though its use was probably limited to the very wealthiest of the provincial kataphraktoi, aristocrats serving in the army, members of some guards units and the imperial household. The construction of horse armour was probably somewhat varied; including bardings composed of metal or rawhide lamellae, or soft armour of quilted or felted textile. The historian John Birkenmeier has stated: "The Byzantines, like their Hungarian opponents, relied on mailed lancers astride armored horses for their first charge."[94]

Equipment: Artillery

The Komnenian army had a formidable artillery arm which was particularly feared by its eastern enemies. Stone-firing and bolt-firing machines were used both for attacking enemy fortresses and fortified cities and for the defence of their Byzantine equivalents. In contemporary accounts the most conspicuous engines of war were stone-throwing trebuchets, often termed helepolis (city-takers); both the man-powered and the more powerful and accurate counterweight trebuchets were known to the Byzantines.[95] The development of the trebuchet, the largest of which could batter down contemporary defensive walls, was attributed to the Byzantines by some western writers.[96] Additionally, the Byzantines also used long range, anti-personnel, bolt firing machines such as the 'great crossbow,' which was often mounted on a mobile chassis, and the 'skein-bow' or 'espringal' which was a torsion device using twisted skeins of silk or sinew to power two bow-arms.[97] The artillerists of the Byzantine army were accorded high status, being described as "illustrious men." The emperor John II and the generals Stephanos and Andronikos Kontostephanos, both leading commanders with the rank of megas doux, are recorded personally operating siege engines.[98]

Troop types

The Byzantine Empire was a highly developed society with a long military history and could recruit soldiers from various peoples, both within and beyond its borders; as a result of these factors a wide variety of troop types were to be found in its army.

Infantry

With the notable exception of the Varangians, the Byzantine infantry of the Komnenian period are poorly described in the sources. The emperors and aristocracy, who form the primary subjects of contemporary historians, were associated with the high-status heavy cavalry and as a result the infantry received little mention.[99]

Varangians

The Varangian Guard were the elite of the infantry. In the field they operated as heavy infantry, well armoured and protected by long shields, armed with spears and their distinctive two-handed Danish axes.[100] Unlike other Byzantine heavy infantry their battlefield employment appears to have been essentially offensive in character. In both of the battles in which they are recorded as playing a prominent role they are described as making aggressive attacks. At Dyrrhachion they defeated a Norman cavalry charge but then their counterattack was pushed too far and, finding themselves unsupported, they were broken.[101] At Beroia the Varangians were more successful, with John II commanding them personally, they assaulted the Pecheneg wagon fort and cut their way into it, achieving a very complete victory.[102] It is likely, given their elite status and their constant attendance on the emperor, that the Varangians were mounted on the march though they usually fought on foot.[103] It has been estimated that throughout Alexios I's reign, some 4,000–5,000 Varangians in total joined the Byzantine army.[104] Before he set out to relieve Dyrrhachion in 1081, the emperor left 300 Varangians to guard Constantinople.[105] After the defeat, Alexios left 500 Varangians to garrison Kastoria in an unsuccessful attempt to halt the Norman advance.[106] At Dyrrhachion there were 1,400 Varangians while at Beroia, only 480–540 were present. This suggests that emperors usually only brought around 500 Varangians for personal protection on campaigns, unless they needed a particularly strong force of infantry.[107] A garrison of Varangians was also stationed in the city of Paphos in Cyprus during the Komnenian period, until the island's conquest by King Richard I.[108]

Native heavy infantry

Heavy infantry are almost invisible in the contemporary sources. In the Macedonian period a heavy infantryman was described as a skoutatos (shieldbearer) or hoplites. These terms are not mentioned in 12th-century sources; Choniates used the terms kontophoros and lonchephoros (spearbearer/spearman). Choniates' usage was, however, literary and may not accurately represent contemporary technical terminology. Byzantine heavy infantry were armed with a long spear (kontos or kontarion) but it is possible that a minority may have been armed with the menavlion polearm. They carried large shields, and were given as much armour as was available. Those in the front rank, at least, might be expected to have metal armour, perhaps even a klivanion.[109] The role of such infantrymen, drawn up in serried ranks, was largely defensive. They constituted a bulwark which could resist enemy heavy cavalry charges, and formed a movable battlefield base from which the cavalry and other more mobile troops could mount attacks, and behind which they could rally.[110]

Peltasts

The type of infantryman called a peltast (peltastēs) is far more heavily referenced in contemporary sources than the “spearman”. Although the peltasts of Antiquity were light skirmish infantry armed with javelins, it would be unsafe to assume that the troops given this name in the Komnenian period were identical in function; indeed, Byzantine peltasts were sometimes described as “assault troops”.[111] Komnenian peltasts appear to have been relatively lightly equipped soldiers capable of great battlefield mobility, who could skirmish but who were equally capable of close combat.[112] Their arms may have included a shorter version of the kontarion spear than that employed by the heavy infantry.[113] At Dyrrachion, for example, a large force of peltasts achieved the feat of driving off Norman cavalry.[114] Peltasts were sometimes employed in a mutually supportive association with heavy cavalry.[115]

Light infantry

The true skirmish infantry, usually entirely unarmoured, of the Byzantine army were the psiloi. This term included foot archers, javelineers and slingers, though archers were sometimes differentiated from the others in descriptions. The psiloi were clearly regarded as being quite separate from the peltasts.[116] Such troops usually carried a small buckler for protection and would have had an auxiliary weapon, a sword or light axe, for use in a close combat situation.[117] These missile troops could be deployed in open battle behind the protective ranks of the heavy infantry, or thrown forward to skirmish.[118] The light troops were especially effective when deployed in ambush, as at the Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir in 1177.[119]

Cavalry

The earlier Byzantine heavy cavalryman, who combined the use of a bow with a lance for close combat, seems to have disappeared before the Komnenian age. The typical heavy cavalryman of the Komnenian army was a dedicated lancer, though armoured horse-archers continued to be employed.[120]

Heavy cavalry

The heavy cavalry were the social and military elite of the whole army and were considered to be the pre-eminent battle winners. The charge of the lancers, and the subsequent melee, was often the decisive event in battle.[121] The lance-armed heavy cavalry of the Komnenian army were of two origins, firstly ‘Latin knights', and secondly native kataphraktoi.

Latin knights

Latin heavy cavalry was recruited from the warriors and knights of Italy, France, The Low Countries, Germany and the Crusader States. The Byzantines considered the French to be more formidable mounted warriors than the Germans.[122] Some Latin cavalrymen formed part of the regular soldiery of the empire and were supported by pay from the imperial treasury, or by pronoia grants, and were organised into formal regiments. Regular Latin 'knightly' heavy cavalry were part of the guard, with individual Latins or those of Western descent to be found in the imperial household, others were grouped into a formation later known as the latinikon. Alternatively, bands of mercenary knights were often hired for the duration of a particular campaign. The charge of the western knight was held in considerable awe by the Byzantines; Anna Komnene stated that "A mounted Kelt [an archaism for a Norman or Frank] is irresistible; he would bore his way through the walls of Babylon."[123] The Latins’ equipment and tactics were identical to those of their regions of origin; though the appearance and equipment of such troops must have become progressively more Byzantine the longer they were in the emperor's employ. Some Latin soldiers, for example the Norman Roger son of Dagobert, became thoroughly integrated into Byzantine society. The descendants of such men, including the general Alexios Petraliphas and the naval commander Constantine Frangopoulos (“son-of-a-Frank”), often remained in military employ.[124] The son of the Norman knight Roger son of Dagobert, John Rogerios Dalassenos, married a daughter of John II, was made caesar and even made an unsuccessful bid for the imperial throne.[125]

Kataphraktoi

The native kataphraktoi were to be found in the imperial oikos, some imperial guards units and the personal guards of generals, but the largest numbers were found within the provincial tagmata. The level of military effectiveness, especially the quality of the armour and mount, of the individual provincial kataphraktos probably varied considerably, as both John II and Manuel I are recorded as employing formations of “picked lancers” who were taken from their parent units and combined. This approach may have been adopted in order to re-create the concentration of very effective heavy cavalry represented by the Imperial Tagmata of former times.[126] The kataphraktoi were the most heavily armoured type of Byzantine soldier and a wealthy kataphraktos could be very well armoured indeed. The Alexiad relates that when the emperor Alexios was simultaneously thrust at from both flanks by lance-wielding Norman knights, his armour was so effective that he suffered no serious injury.[127]

In the reign of Alexios I, the Byzantine kataphraktoi proved to be unable to withstand the charge of Norman knights, and Alexios, in his later campaigns, was forced to use stratagems which were aimed at avoiding the exposure of his heavy cavalry to such a charge.[128] Contemporary Byzantine armour was probably more effective than that of Western Europe therefore reasons other than a deficit in armour protection must be sought for the poor performance of the Byzantine cavalry. It is probable that the Byzantine heavy cavalry traditionally made charges at relatively slow speed, certainly the deep wedge formations described in Nikephoros II Phokas’ day would have been impossible to deploy at anything faster than a round trot. In the course of the late 11th century the Normans, and other Westerners, evolved a disciplined charge at high speed which developed great impetus, and it is this which outclassed the Byzantines.[129] The role of the couched lance technique, and the connected development of the high-cantled war saddle, in this process is obscure but may have had considerable influence.[130]

There is evidence of a relative lack of quality warhorses in the Byzantine cavalry.[131] The Byzantines may have suffered considerable disruption to access to Cappadocia and Northern Syria, traditional sources of good quality cavalry mounts, in the wake of the fall of Anatolia to the Turks. However, by the reign of Manuel I the Byzantine kataphraktos was the equal of his Western counterpart.[132] Although Manuel was credited by the historian Kinnamos with introducing Latin 'knightly' equipment and techniques to his native cavalry, it is likely that the process was far more gradual and began in the reign of Alexios.[133] Manuel's enthusiastic adoption of the western pastime of jousting probably had beneficial effects on the proficiency of his heavy cavalry. The kataphraktos was famed for his use of a fearsome iron mace in melee combat.[134]

Koursores

A category of cavalryman termed a koursōr (pl. koursores) is documented in Byzantine military literature from the sixth century onwards. The term is a transliteration of the Latin cursor with the meaning 'raider' (from cursus: course, line of advance, raid, running, speed, zeal - in Medieval Latin a term for a raider or brigand was cursarius, which was the origin of 'corsair'). According to one theory, it is posited as the etymological root of the term hussar, used for a later cavalry type. The koursōr had a defined tactical role but may or may not have been an officially defined cavalry type. Koursores were mobile close-combat cavalry and may be considered as being drawn from the more lightly equipped kataphraktoi. The koursores were primarily intended to engage enemy cavalry and were usually placed on the flanks of the main battle line. Those on the left wing, termed defensores, were placed to defend that flank from enemy cavalry attack, whilst the cavalry placed on the right wing, termed prokoursatores, were intended to attack the enemy's flank. Cavalry on detached duty, such as scouting or screening the main army, were also called prokoursatores. It is thought that this type of cavalry were armed identically to the heavy kataphraktoi but were armoured more lightly, and were mounted on lighter, swifter horses. Being relatively lightly equipped they were more suited to the pursuit of fleeing enemies than the heavyweight kataphraktoi.[135] In the Komnenian period, the more heavily equipped of the kataphraktoi were often segregated to create formations of "picked lancers," presumably the remainder, being more lightly equipped, provided the koursores. A type of cavalry, differentiated from both horse archers and those with the heaviest armour, is referred to by Kinnamos in 1147 as forming a sub-section of a Byzantine army array; they are described as "those who rode swift horses," indicating that they were koursores, though the term itself is not employed.[136]

Light cavalry

The light cavalry of the Komnenian army consisted of horse-archers. There were two distinct forms of horse-archer: the lightly equipped skirmisher and the heavier, often armoured, bow-armed cavalryman who shot from disciplined ranks. The native Byzantine horse-archer was of the latter type. They shot arrows by command from, often static, ranks and offered a mobile concentration of missile fire on the battlefield.[137] The native horse-archer had declined in numbers and importance by the Komnenian period, being largely replaced by soldiers of foreign origins.[138] However, in 1191 Isaac Komnenos of Cyprus is recorded firing arrows at Richard I of England from horseback during the latter's conquest of Cyprus.[139] This suggests that mounted archery remained a martial skill practised within the upper reaches of Byzantine aristocracy.

Turks from the Seljuk and Danishmend realms of central and eastern Anatolia, and those Byzantinised Turks and Magyars settled within the Empire, such as the Vardariots, supplied the bulk of the heavy horse-archers of the Komnenian army. Towards the end of the period Alans were also supplying this type of cavalry. Such horse archers were often highly disciplined. The Byzantine horse-archers (termed doryphoroi – indicating guard status) at Sozopolis in 1120 performed a feigned flight manoeuvre, always demanding the greatest self-confidence and discipline, which led to the taking of the city from the Turks.[140] Given that they were usually armoured, even if it was comparatively light armour, this type of horse-archer also had the capability to fight with melee weapons in close combat.[141]

Skirmish horse-archers, usually unarmoured, were supplied by the Turkic Pechenegs, Cumans and Uzes of the steppes.[142] These troops were ideal scouts and were adept at harassment tactics. They usually attacked as a swarm and were very difficult for a more heavily equipped enemy to bring into close combat. Light horse-archers were also effective as a screening force, preventing an enemy discerning the dispositions of other troops (for example at the Battle of Sirmium).[143]

Development

Alexios I inherited an army which had been painstakingly reconstituted through the administrative efforts of the able eunuch Nikephoritzes. This army, though small due to the loss of territory and revenue, was in its nature similar to that of earlier Byzantine armies back as far as Nikephoros Phokas and beyond; indeed some units could trace their history back to Late Roman times. This rather traditional Byzantine army was destroyed by the Italo-Normans at Dyrrachion in 1081.[144] In the aftermath of this disaster Alexios laid the foundations of a new military structure. He raised troops entirely by ad hoc means: raising the regiment of the archontopouloi from the sons of dead soldiers and even pressing heretic Paulicians from Philippopolis into the ranks. The only Anatolian troops that are mentioned as part of the army of Alexios are the Chomatenes.[145] Most important is the prominent place in this new army of Alexios' extended family and their many connections, each aristocrat bringing to the field his armed retinue and retainers. Before campaigning against the Pechenegs in 1090 he is recorded as summoning "his kinsmen by birth or marriage and all the nobles enrolled in the army." From pure necessity an army based on a model derived ultimately from Classical Antiquity was transformed, like the empire as a whole, into a type of family business. At this point the army could be characterised as being a feudal host with a substantial mercenary element.[146]

Later in his reign, when the empire had recovered territory and its economic condition had improved, the increased monetary revenue available allowed Alexios to impose a greater regularity on the army, with a higher proportion of troops raised directly by the state; however, the extended imperial family continued to play a very prominent role. Alexios, it is recorded, personally educated an elite corps of young, aspiring commanders. The best of them were then given commands in the army. In this manner Alexios improved both the quality of his field officers and the level of loyalty they had to him.[147] This was the army that his successors inherited and further modified.

Under John II, a Macedonian division was maintained, and new native Byzantine troops were recruited from the provinces. As Byzantine Anatolia began to prosper under John and Manuel, more soldiers were raised from the Asiatic provinces of Thrakesion, Mylasa and Melanoudion, Paphlagonia and even Seleucia (in the south-east). Soldiers were also drawn from defeated peoples, who were forcibly recruited into the army; examples include the Pechenegs (horse archers) and Serbs, who were transplanted as military settlers to the regions around Moglena and Nicomedia respectively.[148] Native troops were organised into regular units and stationed in both the Asian and European provinces. Later Komnenian armies were also often reinforced by allied contingents from Antioch, Serbia and Hungary, yet even so they generally consisted of about two-thirds Byzantine troops to one-third foreigners. Units of archers, infantry and cavalry were grouped together so as to provide combined arms support to each other. Field armies were divided into a vanguard, main body and rearguard. The vanguard and rearguard could operate independently of the main body, where the emperor would be. This suggests that subordinate commanders were able to take tactical initiatives, and that the officer class was well trained and trusted by the emperor.[149] John fought fewer pitched battles than either his father or son. His military strategy revolved around sieges and the taking and holding of fortified settlements, in order to construct defensible frontiers. John personally conducted approximately twenty five sieges during his reign.[150]

The emperor Manuel I was heavily influenced by Westerners (both of his empresses were Franks) and at the beginning of his reign he is reported to have re-equipped and retrained his native Byzantine heavy cavalry along Western lines.[151] It is inferred that Manuel introduced the couched lance technique, the close order charge at speed and increased the use of heavier armour. Manuel personally took part in knightly tournaments in the Western fashion; his considerable prowess impressed Western observers.[152] Manuel organised his army in the Myriokephalon campaign as a number of 'divisions' each of which could act as small independent army. It has been argued that it was this organisation which allowed the greater part of his army to survive the ambush inflicted on it by the Seljuk Turks.[153] Indeed, it was a stock of Byzantine writing to contrast the order of the Byzantine battle array with the disorder of barbarian military dispositions.[154] Manuel is credited with greatly expanding the pronoia system. In the reign of Alexios I pronoia grants were limited to members of the imperial family and their close connections; Manuel extended the system to include men of considerably more lowly social origins and foreigners. Both classes of new pronoiar infuriated the historian Choniates, who characterised them as: tailors, bricklayers and "semi-barbarian runts".[155]

Permanent military camps were established in the Balkans and in Anatolia, they are first mentioned during the reign of Alexios I (Kypsella and Lopadion), but as Lopadion is recorded as being newly fortified in the reign of John II it is the latter who seems to have fully realised the advantages of this type of permanent camp.[156] The main Anatolian camp was at Lopadion on the Rhyndakos River near the Sea of Marmara, the European equivalent was at Kypsella in Thrace, others were at Sofia (Serdica) and at Pelagonia, west of Thessalonica. Manuel I rebuilt Dorylaion on the Anatolian plateau to serve the same function for his Myriokephalon campaign of 1175–76.[157] These great military camps seem to have been an innovation of the Komnenian emperors, possibly as a more highly developed form of the earlier aplekta (military stations established along major communication routes), and may have played an important role in the improvement in the effectiveness of the Byzantine forces seen in the period. The camps were used for the training of troops and for the preparation of armies for the rigours of campaign; they also functioned as supply depots, transit stations for the movement of troops and concentration points for field armies.[158] It has also been suggested that the regions around these military bases were the most likely areas for pronoia grants to be located.[159]

Legacy

The Komnenian Byzantine army was a resilient and effective force but it was over-reliant on the leadership of an able emperor. After the death of Manuel I in 1180 able leadership was wanting. First there was Alexios II, a child-emperor with a divided regency, then a tyrant, Andronikos I, who attempted to break the power of the aristocracy who provided the leadership of the army, and finally the incompetents of the Angeloi dynasty. Weak leadership allowed the Komnenian system of rule through the extended imperial family to break down. The regionally based interests of the powerful aristocracy were increasingly expressed in armed rebellion and secession; mutual distrust between the aristocracy and the bureaucrats of the capital was endemic and both these factors led to a disrupted and fatally weakened Empire.[160][161]

When Constantinople fell to the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Byzantine successor states established at Epirus, Trebizond and especially Nicaea based their military systems on the Komnenian army. The success of the Empire of Nicaea in particular in reconquering former Byzantine territories (including Constantinople) after 1204, may be seen as evidence of the strengths of the Komnenian army model. Though there is some reason to restrict the term Komnenian army solely to the period of the rule of the Komnenian emperors, the real break with this system came after the recovery of Constantinople in 1261, when the Byzantine army became sufficiently distinct from its earlier form to deserve a separate identity as the Palaiologan army. The Byzantine Empire enjoyed an economic and cultural renaissance during the 12th century and the Komnenian army played a crucial part in providing the political and territorial stability which allowed this cultural flowering.[162]

Timeline

- 1081 – Alexios I led an army of 20–25,000 men to attack the invading Normans, but was heavily defeated at the Battle of Dyrrhachion.[163][164]

- 1091 – A massive invasion by the Pechenegs was defeated at the Battle of Levounion by an army of Byzantines with the assistance of 5,000 Vlach mercenaries, 500 Flemish knights, and supposedly 40,000 Cumans.[165]

- 1092–1097 – John Doukas, the megas doux, led campaigns on both land and sea and was responsible for the re-establishment of firm Byzantine control over the Aegean, the islands of Crete and Cyprus and the western parts of Anatolia.[166]

- 1107–1108 - The Italo-Normans under Bohemond invaded the western Balkans. Alexios' response was cautious, he relied on defending mountain passes in order to keep the Norman army pent up on the Albanian coast, where they were besieging Dyrrhachion. Using delaying tactics and not offering battle, while his navy cut all communications with Italy, Alexios starved and harassed the Normans into capitulation. Bohemond was forced to become a vassal of the emperor for his principality of Antioch, but was unable or unwilling to put this agreement into effect.[167]

- 1116 - the Battle of Philomelion consisted of series of clashes over a number of days between a Byzantine expeditionary army under Alexios I and the forces of the Sultanate of Rûm under Sultan Malik Shah; the Byzantine victory ensured a peace treaty advantageous to the Empire.[168]

- 1119 - The Seljuks had pushed into the southwest of Anatolia cutting the land route to the Byzantine city of Attalia and the region of Cilicia. John II responded with a campaign which recaptured Laodicea and Sozopolis, restoring Byzantine control of the region and communications with Attalia.[169]

- 1122 – At the Battle of Beroia, realizing the Imperial army was making little headway, John II personally led 500 Varangians forward to smash through the Pecheneg defensive wagon fort. As an independent people the Pechenegs disappear from historical records following this defeat.[170]

- 1128 - An army led by John II inflicted a significant defeat on the Hungarians at the Battle of Haram on the River Danube.[171]

- 1135 – After successfully capturing Kastamon, John II marched on to Gangra which capitulated and was garrisoned with 2,000 men.[172]

- 1137-1138 - John II recovered control of Cilicia, enforced the vassalage of the crusader Principality of Antioch and campaigned against the Muslims of Northern Syria. The city of Shaizar was besieged and bombarded with 18 large mangonels (traction trebuchets).[173]

- 1140 - John II besieged but failed to take the city of Neocaesarea. The Byzantines were defeated by the conditions rather than by the Turks: the weather was very bad, large numbers of the army's horses died, and provisions became scarce.[174]

- 1147 - At the Battle of Constantinople a Byzantine army defeated part of the crusading army of Conrad III of Germany outside the walls of the city. Conrad was forced to come to terms and have his army rapidly shipped across the Bosphoros to Anatolia.[175]

- 1148 - Before setting out to recapture Corfu, Manuel I diverted his army to the Danube after learning of a Cuman raid. Leaving the bulk of the army south of the river, the emperor personally crossed the Danube with 500 cavalry and defeated the Cuman raiding party.[176]

- 1149 – Manuel I commanded 20–30,000 men at the siege of Corfu supported by a fleet of 50 galleys along with numerous small pirate galleys, horse transports, merchantmen, and light pirate skiffs.[177]

- 1155–56 – The generals Michael Palaiologos and John Doukas were sent with 10 ships to invade Apulia.[178] A number of towns, including Bari, and most of coastal Apulia were captured, however, the expedition ultimately failed, despite the reinforcements sent by the emperor because the Byzantine fleet of 14 ships was vastly outnumbered by the Norman fleet.[179] The Byzantine army never numbered more than a few thousand and consisted of Cuman, Alan, and Georgian mercenaries.[180][181]

- 1158 – At the head of a large army, Manuel I marched against Thoros II of Armenia. The emperor left the main body of the army at Attaleia while he led 500 cavalry to Seleukeia and from there entered the Cilician plain as part of a surprise attack.[182]

- 1165 – The Kingdom of Hungary was invaded by a Byzantine army and the city of Zeugminon was placed under siege. The commanding general, and future emperor, Andronikos I Komnenos personally adjusted the 4 helepoleis (counterweight trebuchets) that were used to bombard the city.[183]

- 1166 – Two Byzantine armies were dispatched in a vast pincer movement to ravage the Hungarian province of Transylvania. One army crossed the Walachian Plain and entered Hungary through the Transylvanian Alps (Southern Carpathians), whilst the other army made a wide circuit to the south-western Russian principality of Galicia and, with Galician aid, crossed the Carpathian Mountains.[184]

- 1167 – With an army of 15,000 men, general Andronikos Kontostephanos scored a decisive victory over the Hungarians at the Battle of Sirmium.[185]

- 1169 – A Byzantine fleet of about 150 galleys, 10-12 large transports and 60 horse transports under megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos was sent to invade Egypt.[186] The combined Byzantine-Crusader army successfully captured the cities of Tounion and Tinnis before besieging Damietta. The Byzantine army launched several assaults and were about to capture the city when King Amalric made peace and withdrew. The Byzantine fleet withdrew after a siege of over 50 days and sailed away in some haste, leaving only 6 triremes for Kontostephanos. With an escort, the general decided to march via Jerusalem back to Constantinople.[187]

- 1175 – The Emperor dispatched Alexius Petraliphas with 6,000 men to capture Gangra and Ancyra, however the expedition failed due to heavy resistance from the Turks.[188]

- 1176 – In his last attempt to capture Iconium, Manuel I led a large army of 25–40,000 men which was supported by 3,000 wagons carrying supplies and siege engines.[189][190] The campaign ultimately ended in failure after suffering defeat at the Battle of Myriokephalon.

- 1177 – Andronikos Kontostephanos led a fleet of 150 ships in another attempt to conquer Egypt, the force returned home after landing at Acre. The refusal of Count Philip of Flanders to co-operate with the Byzantine force led to the abandonment of the campaign.[191] A large raiding force of Seljuk Turks was destroyed by a Byzantine army commanded by John Komnenos Vatatzes in an ambush in Western Anatolia (Battle of Hyelion and Leimocheir).[192]

- 1185 - Following the sack of the city of Thessalonica by the Siculo-Normans of the Kingdom of Sicily, the Norman army was routed at the Battle of Demetritzes by a Byzantine army led by Alexios Branas. Thessalonica was re-occupied by the Byzantines soon after the battle.[193]

- 1187 – After a successful campaign against the Bulgarians and Vlachs, General Alexios Branas rebelled. Conrad of Montferrat assembled 250 knights and 500 infantry from the Latin population of Constantinople to join Emperor Isaac II Angelos's army of 1,000 men. Together they defeated and killed the rebel commander outside the city walls.[194] Later in the year, the Emperor returned to Bulgaria with 2,000 men (possibly cavalry) to quell the rebellion.[195]

- 1189 – On the orders of Emperor Isaac II, the protostrator Manuel Kamytzes (with 2,000 cavalry) attempted to ambush part of Frederick Barbarossa's army near Philippopolis but was defeated.[196]

- 1198–1203 – Successive revolts by semi-autonomous magnates and provincial governors. Those of Dobromir Chrysos, Ivanko and John Sypridonakes in Macedonia and Thrace are suppressed, those of Leo Chamaretos and Leo Sgouros in Greece succeed in establishing their authority.[197]

- 1204 – When the Fourth Crusade reached Constantinople, the city was defended by a garrison of 10,000 men including the Imperial Guard of 5,000 Varangians.[198]

Notes

- Haldon (1999), p. 104.

- See Birkenmeier for the use of this term.

- Angold, pp. 94-98

- Angold, pp. 106-111

- Angold, p. 127

- Birkemeier, p. 66

- Birkenmeier, pp. 83-84

- Birkenmeier, pp. 148-154

- Birkenmeier, pp. 1-2

- Birkenmeier, p. 139.

- Treadgold (1997), p. 680.

- Haldon (1999), p. 104.

- Treadgold (2002), p. 236.

- Haldon (1999), p. 104.

- Birkenmeier, p. 197.

- Haldon (1999), p. 104.

- Birkenmeier, p. 151.

- Birkenmeier, p. 180.

- Haldon (1999), p. 105.

- Choniates, p. 224

- Brand p. 104

- Birkenmeier, pp. 154-158

- Birkenmeier, p. 155

- Angold, pp. 131-133

- Haldon (1999), p. 126

- Haldon (1999), p. 128

- Magdalino, pp. 175-177, 231-233

- Ostrogorsky (1971), p. 14

- Birkenmeier, p. 154

- Heath, Ian; McBride, Angus (1995). Byzantine Armies: AD 1118–1461.pp. 12–19.

- Heath, p. 13.

- Haldon (1999), pp. 115–117.

- Later references to archontopouloi do not make it clear whether the men given this title were part of a fighting regiment or merely young aristocrats attached to the emperor's household. The Byzantine army had a long history of elite formations raised as fighting regiments declining over time into merely ornamental appendages of the imperial court (the Scholae Palatinae in Justinian the Great's time was manned by unwarlike rich civilians who had bought positions in the regiment as a social perk). See Bartusis, p. 206. Birkenmeier regards the archontopouloi as being primarily a 'palace training corps' for officers, and their deployment as a field regiment by Alexios I as an isolated expedient. See Birkenmeier, p. 158 (footnote)

- The hetaireia are mentioned by Kinnamos as being present at the Battle of Sirmium in 1167 and a megas hetaireiarchēs named John Doukas is recorded (Magdalino, p, 344). In the later 12th century the hetaireia was recorded by Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger as being customarily composed of young Byzantine nobles (Kazhdan 1991, p. 925).

- J. Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople, p. 159

- W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 617

- Magdalino, p. 231, Haldon (1999), p. 120. Though probably in origin horse archers of Magyar ancestry, at an undetermined time, possibly after the Komnenian period they became a type of military police.

- The distinction between the oikeioi and the vestiaritai is not clear, though the vestiaritai appear to have been considered as composing part of the emperor's household. One function of the vestiaritai was guarding the public and private imperial treasuries (Magdalino, p. 231).

- Heath, p. 14. Exceptionally, the megas doux Andronikos Kontostephanos is described by the historian Kinnamos as being surrounded by those troops usually attendant on the emperor, when he commanded the Byzantine army at the Battle of Sirmium.

- Angold, p. 213. Lampardas was sebastos, oikeios vestiaritēs and chartoularios, Magdalino p. 505.

- Angold, p. 128.

- Haldon (1999), p. 118.

- Choniates, p. 102

- Birkenmeier, p. 162

- Magdalino, pp. 232-233

- Kinnamos, 71, 11. 13–15. "... some Romans from the register (katalogon) of infantry."

- Birkenmeier, p. 97

- Birkenmeier, p. 200

- Birkenmeier, p. 62

- Birkenmeier, p. 162

- Heath, Ian: Armies and Enemies of the Crusades 1096–1291, Wargames Research Group. (1978), p. 28. The sources unequivocally give names to the foreign tagmata only in the Nicaean period, but references to formations of troops, often translated as 'divisions,' from these ethnic groups abound in the Komnenian sources. See Birkenmeier, p. 93 for John II's army at the Siege of Shaizar, which was organised in three divisions: 'Macedonians' (native Byzantines), 'Kelts' (Normans and Franks) and 'Pechenegs' (Turkic steppe nomads).

- W. Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, p. 614

- Magdalino, p. 232

- I. Heath, Byzantine Armies: AD 1118–1461, p. 33

- Magdalino, p. 232

- Magdalino, pp. 248-249

- Angold, pp. 112 and 157

- Ostrogorsky 1971, p. 14

- Angold, pp. 213–214

- Ostrogorsky (1971), p. 15

- Brand p. 5.

- Mitchell, pp.99-103

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 25.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Cavalryman, Oxford (2009), p. 36.

- Komnene, Alexiad, Anna Comnena, trans E. R. A. Sewter, pp. 42–43.

- Choniates, p 148

- Deligiannis, P., On the Byzantine Rhomphaia Slingshot 313, July/August 2017, Society of Ancients

- Nicolle, David: Medieval Warfare Source Book, Vol. II London (1996), pp. 75–76, mace use is also mentioned by Kinnamos.

- Nicolle, David: Medieval Warfare Source Book, Vol. II London (1996), p. 74.

- Nishimura (1996)

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 23.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 22

- Grotowski, pp. 151-154, 166-170

- Grotowski, pp. 177-179

- Dawson, Timothy: Kresmasmata, Kabbadion, Klibanion: Some Aspects of Middle Byzantine Military Equipment Reconsidered Archived 2011-02-16 at the Wayback Machine, Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 22 (1998), pp. 38–50.

- Grotowski, pp. 137-151 (klivanion), 154-162 (scale and mail)

- The general Andronikos Kontostephanos is described as donning his mailshirt and then "the rest of his armour" just before the Battle of Sirmium, a good indicator that the kivanion was indeed worn over mail. Choniates, p. 87.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 23 (illustration with notes).

- Grotowski, pp. 170-174

- Nicolle, David: Medieval Warfare Source Book, Vol. II London (1996), p. 78.

- Grotowski, pp. 166-170

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 23..

- Oman, Charles: The Art of War in the Middle Ages, Vol. I: 378-1278AD, London (1924). pp. (illustration facing) 190, and 191.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), pp. 20–21.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), p. 61.

- D'Amato, p. 11

- D'Amato, p. 33

- D'Amato, p. 47

- Nicolle, David (1996), p. 163..

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Infantryman, Oxford (2007), pp. 20–21

- For example: Komnene, Alexiad, p. 42. "... Alexius covered his face, drawing down the vizor fastened to the rim of his helmet..." Both Choniates and Kinnamos describe the Emperor Manuel I having armour covering his face.

- Nicolle (1996) p. 163"

- Choniates, p. 88

- Birkenmeier, p. 121

- Birkenmeier pp.188–189

- Nicolle, p173

- Nicolle, pp. 173–174, the espringal is depicted, in the form of a fairly detailed diagram, in an 11th-century Byzantine manuscript

- Birkenmeier pp. 189–191

- Birkenmeier, p. 200.

- Birkenmeier, pp. 96, 232.

- Birkenmeier, pp. 62–68.

- Choniates pp. 10–11, Birkenmeier, p. 90.

- Anna Komnene records that the Emperor Alexios I ordered the Varangians to dismount and march at the head of the army, in the opening stages of the Battle of Dyrrachion – Alexiad, IV, 6.

- Blondal, p. 140

- Blondal, p. 123

- Blondal, p. 127

- Blondal, p. 181

- Blondal, p. 137

- Dawson (2007), p. 63.

- Haldon (1999), p. 224.

- Birkenmeier, p.123.

- Birkenmeier, p.241.

- Dawson (2007), p. 59

- Birkenmeier, p. 64.

- Birkenmeier, p. 83.

- "Birkenmeier, p. 64

- Dawson (2007), p. 59"

- Dawson (2007), pp. 53–54.

- Choniates, p. 108

- Haldon (1999), p.216

- Birkenmeier, pp. 215–216.

- Birkenmeier, p. 112

- Anna Komnene, p. 416

- For Frangopoulos see Choniates, p. 290.

- Magdalino, p. 209

- Birkenmeier, pp. 121, 160.

- Komnene, Alexiad, pp. 149–150. The circumstances of the passage make it clear that the incident was in a melee context, no armour would have been proof to a lance propelled by the impetus of a horse charging at speed. Whereas a Western knight would have had merely a padded undergarment and a single layer of mail as protection a well-armoured Byzantine could have had up to four layers of protection to the torso; that is: first a padded kavadion, then a mail shirt, over this a klivanion and then a further layer of quilted protection, the epilorikion, outside all.

- Birkenmeier, pp. 60–70.

- Haldon (2000) pp. 111–112. Western knights usually charged in a shallow formation, usually of two ranks, a formation later termed en haie (like a hedge) in French. Byzantine sources, such as Choniates, often refer to heavy cavalry formations as "phalanxes" (see Birkenmeier, p. 92); this tends to suggest a deeper formation. The deeper the formation the less the speed that can be achieved in a charge.

- Haldon (1999), p. 133

- Birkenmeier, pp. 61–62 (footnote).

- Birkenmeier p. 240.

- Kinnamos, 112, 125, 156–157, 273–274. Kinnamos credits Manuel with the adoption of the long "kite" shield in place of round shields, this is manifestly untrue as Byzantine illustrations of kite shields are found much earlier than Manuel's reign.

- Choniates, p. 89.

- Dawson, Timothy: Byzantine Cavalryman, Oxford (2009), pp. 34–36, 53, 54

- Kinnamos, p. 65

- Nicolle, p. 75.

- Haldon (1999) p. 216-217.

- Heath, p. 24

- Birkenmeier, p. 89.

- Mitchell, 95-98

- Heath (1995), pp. 23, 33.

- Mitchell, pp. 95-98

- Birkenmeier, p. 45

- Birkenmeier, p. 59

- Angold, p. 127.

- Angold, p. 128

- Birkenmeier, p. 97

- Birkenmeier, pp. 92-93

- Birkenmeier, pp. 86-87

- Kinnamos, p. 99.

- Angold, p. 226

- Birkenmeier, p.132

- Haldon (1999), pp. 208-209

- Angold, pp. 225-226

- Kinnamos, p. 38

- Birkenmeier, p. 127

- Choniates pp. 19–21, for John's use of Lopadion as a troop assembly point and as a military base for campaigning from.

- Angold, pp. 226-227

- Angold, pp. 270-271

- Birkemmeier, p. 235

- Birkenmeier, pp. xi-xii, 234-235

- Haldon (2000), p. 134

- Birkenmeier, p. 62

- Birkenmeier, p. 76.

- Angold (1997), p. 150

- Angold, pp. 142-143.

- Birkenmeier, p.78-80

- Norwich, p. 68

- R. D'Amato (2010), p. 5

- Kinnamos, p. 18

- Birkenmeier p. 205.

- Angold, p. 156

- Angold, p. 157

- Birkenmeier, pp. 109-111

- Kinnamos, 76-78

- Choniates, p. 45

- Brand, p. 108.

- Brand, p. 124.

- Birkenmeier, p.151

- Haldon (1999), p. 126

- Kinnamos, 137-138

- Dennis p. 113.

- Angold, p. 177.

- Birkenmeier p. 241.

- Pryor (2006), p.115

- Choniates, p. 96

- Brand p. 219.

- Birkenmeier, p. 180

- Haldon (2000), p. 1980.

- Harris p. 109

- Birkenmeier pp. 134–135

- Angold, p. 272

- Choniates, p. 211

- Choniates, p. 218

- Choniates, p. 224

- Ostrogorsky (1980), pp. 410-411

- Phillips, p. 159

Bibliography

- Primary sources