Capture of Lucknow

The Capture of Lucknow (Hindi: लखनऊ का क़ब्ज़ा, Urdu: لکھنؤ کا قبضہ) was a battle of Indian rebellion of 1857. The British recaptured the city of Lucknow which they had abandoned in the previous winter after the relief of a besieged garrison in the Residency, and destroyed the organised resistance by the rebels in the Kingdom of Awadh (or Oudh, as it was referred to in most contemporary accounts).

| Capture of Lucknow | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indian rebellion of 1857 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Begum Hazrat Mahal | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

31,000 104 guns |

100,000 (?) unknown number of guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

127 killed 595 wounded | Unknown | ||||||

Background

Oudh had been annexed by the East India Company only a year before a general mutiny broke out in the Company's Bengal Army. The annexation had been accompanied by several instances of expropriation of royal and landholders' estates on sometimes flimsy grounds of non-payment of taxes, or difficulties in proving title to lands. Many sepoys (native soldiers) of the Company's Bengal Army had been recruited from high-caste and landowning communities in Oudh. There was increasing unrest in the Bengal Army, as privileges and customary allowances they had previously enjoyed were withdrawn. With uncertainty over their rights to property in Oudh, they felt that their status both as soldiers and citizens was under threat.

When the rebellion broke out in May 1857, it threatened British authority in several areas of India, but most particularly in Oudh, where the resentful dispossessed rulers and landowners joined with the mutinied regiments (Bengal Native troops, and Oudh Irregular units formerly belonging to the Kingdom of Oudh) in what became a national rebellion.

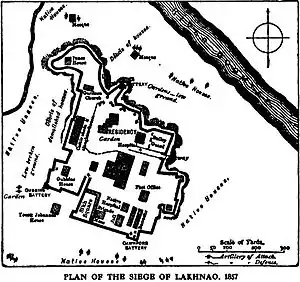

From 1 July to 26 November 1857, the British had withstood the siege of the Residency to the north of the city. When the besieged garrison was finally relieved by the British commander-in-chief, Sir Colin Campbell, the Residency was evacuated, as Campbell's communications were threatened. He returned to Cawnpore (Kanpur) from where the relief expedition had been mounted, with all the civilians evacuated from the Residency and the sick and wounded. However, he left a division of 4,000 men under Sir James Outram to hold the Alambagh, a walled park two miles south of the city.

During the following winter campaigning season, Campbell re-established his communications with Delhi and with Calcutta. He also received fresh reinforcements from Britain and built up a substantial transport and supply column. After capturing Fatehgarh on 1 January 1858, which allowed him to establish control over the countryside between Cawnpore and Delhi, Campbell suggested leaving Oudh alone during 1858, concentrating instead on recapturing the state of Rohilkhand, which was also in rebel hands. However, the Governor General, Lord Canning, insisted that Oudh be recaptured, so as to discourage other potential rebels. Canning wrote

Oudh is not only the rallying point of the sepoys, the place to which they all look, and by the doings in which their own hopes and prospects rise and fall; but it represents a dynasty; there is a King of Oudh "seeking his own".[1][2]

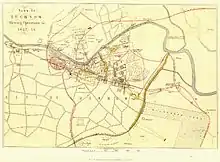

Campbell's advance

Campbell's army consisted of seventeen infantry battalions, twenty-eight cavalry squadrons and 134 guns and mortars,[3] with a large and unwieldy baggage train and large numbers of Indian camp followers. The army crossed the Ganges River in late February, and advanced to rendezvous with Outram at the Alambagh on 1 March. The army was then reorganised into three infantry divisions under Outram, Brigadier Walpole and Brigadier Lugard, and a cavalry division under James Hope Grant. A force of 9,000 Nepalis (not to be confused with the regular Gurkha units of the Bengal Army) was approaching Lucknow from the north, commanded by Brigadier Franks.

The defenders of Lucknow were said to number 100,000. This suspiciously large and round figure reflects the fact that the defenders lacked coordinated leadership, and were largely the personal retinues of landowners, or loosely organised bodies of fighters, whose motives, dedication and equipment varied widely. The British were not able to gain any reliable reports of their numbers. The rebels were nevertheless equipped with large numbers of cannon and had heavily fortified the Charbagh Canal, the city and the palaces and mosques adjoining the Residency to the north of the city. They had however not fortified the northern approaches to the city on the north bank of the Gumti River, which had not seen fighting previously. (During the British relief moves in 1857, the ground had been flooded by monsoon rains.)

Campbell began by repeating his moves of the relief of the Residency the previous year. He moved to the east of the city and Charbagh Canal to occupy a walled park, the Dilkusha Park, although this time he suffered from rebel artillery fire until his own guns could be brought up.

On 5 March, Campbell's engineers constructed two pontoon bridges across the Gumti. Outram's division crossed to the north bank, and by 9 March, they were established north of the city. Under covering fire from his siege guns, his division captured the grandstand of the King of Oudh's racecourse (known as the Chakar Kothi). Meanwhile, Campbell's main body captured La Martiniere (formerly a school for the children of British civilians) and forced their way across the Charbagh Canal with few casualties.

Capture of the main defences

By 11 March, Outram captured two bridges across the Gumti near the Residency (an iron bridge and a nearby stone bridge) although heavy rebel artillery fire forced him to abandon the stone bridge. Meanwhile, Campbell occupied an enclosed palace (the Secundrabagh) and a mosque (the Shah Najaf) with little opposition; these two positions had been the scene of heavy fighting the previous November. In front of him was a block of palace buildings, collectively known as the Begum Kothi. There was severe fighting for these on 11 March, in which 600 or 700 rebels died.

Over the next three days, Campbell's engineers and gunners blasted and tunnelled their way through the buildings between the Begum Kothi and the main rebel position in the King of Oudh's palace, the Kaisarbagh. Meanwhile, Outram's guns bombarded the Kaisarbagh from the north. The main assault on the Kaisarbagh took place on 14 March. Campbell's and Frank's forces attacked from the east, but Campbell surprisingly refused Outram permission to cross the Gumti and take the Kaisarbagh between two fires. As a result, although the Kaisarbagh was easily captured, its defenders were able to retreat without difficulty.

Final capture of Lucknow

Most of the rebels were abandoning Lucknow and scattering into the countryside. Campbell failed to stop most of them, by sending his cavalry after some rebels who had left earlier. Operations temporarily halted while the British reorganised and most regiments fell to looting the captured palaces.

On 16 March, Outram finally recrossed the Gumti, and his division advanced on and stormed the Residency. There were disjointed rebel counter-attacks on the Alambagh and the British positions north of the Gumti, which failed. A rebel force which was supposed to contain Begum Hazrat Mahal, the wife of the dispossessed King of Oudh, and her son Birjis Qadra whom the rebels had proclaimed King, was driven from the Musabagh, yet another walled palace four miles northwest of Lucknow.

The last rebels, 1,200 men under a noted leader, Ahmadullah Shah, also known as the Maulvi of Faizabad, were driven from a fortified house in the centre of the city on 21 March. The city was declared cleared on this date.

Outcome

Campbell had advanced cautiously and had captured Lucknow with few casualties, but by failing to prevent the rebels escaping, he was forced to spend much of the following summer and monsoon season clearing the rebels from the countryside of Oudh. As a result, his army suffered heavy casualties from heatstroke and other diseases.

Outram had also failed to protest his orders not to advance on 14 March, which had allowed most rebels to escape. Outram was Civil Commissioner for Oudh in addition to his military command, and may have allowed his hopes for pacification and reconciliation to override his soldier's instincts.

Rebel casualties were hard to estimate. British troops usually executed any prisoners they captured, whether armed or not. One of the prominent British casualties was William Hodson, who led an irregular cavalry unit and also served as an Intelligence officer, killed during the capture of the Begum Kothi on 11 March.

Notes

- Edwardes, p.123

- The last phrase is associated with the proclamation of Charles Edward Stuart, a pretender to the English and Scottish thrones, when he launched an unsuccessful uprising in 1745

- Hibbert, p.356

References

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The Great Mutiny - India 1857. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-004752-2.

- Edwardes, Michael (1963). Battles of the Indian Mutiny. Pan. ISBN 0-330-02524-4.