Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas

Chiapa de Corzo (Spanish: [ˈtʃjapa ðe ˈkoɾso] (![]() listen)) is a small city and municipality situated in the west-central part of the Mexican state of Chiapas. Located in the Grijalva River valley of the Chiapas highlands, Chiapa de Corzo lies some 15 km (9.3 mi) to the east of the state capital, Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Chiapa has been occupied since at least 1400 BCE, with a major archeological site which reached its height between 700 BCE and 200 CE. It is important because the earliest inscribed date, the earliest form of hieroglyphic writing and the earliest Mesoamerican tomb burial have all been found here. Chiapa is also the site of the first Spanish city founded in Chiapas in 1528. The "de Corzo" was added to honor Liberal politician Angel Albino Corzo.

listen)) is a small city and municipality situated in the west-central part of the Mexican state of Chiapas. Located in the Grijalva River valley of the Chiapas highlands, Chiapa de Corzo lies some 15 km (9.3 mi) to the east of the state capital, Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Chiapa has been occupied since at least 1400 BCE, with a major archeological site which reached its height between 700 BCE and 200 CE. It is important because the earliest inscribed date, the earliest form of hieroglyphic writing and the earliest Mesoamerican tomb burial have all been found here. Chiapa is also the site of the first Spanish city founded in Chiapas in 1528. The "de Corzo" was added to honor Liberal politician Angel Albino Corzo.

Chiapa de Corzo | |

|---|---|

Town & Municipality | |

La Pila Fountain in the main square | |

Coat of arms | |

Chiapa de Corzo Location in Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 16°42′25″N 93°00′50″W | |

| Country | |

| State | Chiapas |

| Founded | 1528 |

| Municipal Status | 1915 |

| Government | |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 906.7 km2 (350.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation (of seat) | 420 m (1,380 ft) |

| Population (2010) Municipality | |

| • Municipality | 87,603 |

| • Seat | 45,077 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (US Central)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central) |

| Postal code (of seat) | 29160 |

| Area code(s) | 961 |

| Climate | Aw |

| Website | www |

Demographics

As of 2010, the municipality had a total population of 87,603.[1]

As of 2010, the city of Chiapa de Corzo had a population of 45,077.[1] Other than the city of Chiapa de Corzo, the municipality had 404 localities, the largest of which (with 2010 populations in parentheses) were: Jardínes del Grijalva (2,881), classified as urban, and Julián Grajales (2,394), Salvador Urbina (1,653), Las Flechas (1,579), Galecio Narcía (1,553), El Palmar (San Gabriel) (1,477), Juan del Grijalva (1,428), Ignacio Allende (1,396), Venustiano Carranza (1,301), Narciso Mendoza (1,193), Nicolás Bravo (1,184), América Libre (1,073), and Nuevo Carmen Tonapac (1,010), classified as rural.[1]

Town and municipality

The town/municipality is located about fifteen km from the state capital of Tuxtla Gutiérrez and connected to the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas via Federal Highway 190 also known as the Panamerican Highway.[2] The town is located along the Grijalva River and has one of the main docks along this waterway. The town is laid out in Spanish style, centered on a very large plaza which the municipality claims is larger than the Zocalo, or main plaza of Mexico City.[3] (sec.[2]

This plaza has a number of important features. The largest and best known is the La Pila fountain. This was constructed in 1562 in Moorish style, made of brick in the form of a diamond.[2] The structure is attributed to Dominican brother Rodrigo de León.[4] It measures fifty two meters in circumference and twelve meters in height. It has eight arches and a cylindrical tower which occasionally functioned as a watchtower.[3] Another important feature is the La Pochota kapok tree. According to tradition, the Spanish town was founded around this tree. The last feature is a clock tower which was constructed in the 1950s. The town's main structures are centered on this plaza, including the municipal palace and the former home of Liberal governor Angel Albino Corzo, for whom the town is partially named. One side of the plaza is taken by the “portales” a series of arches initially built in the 18th century, which contain a number of businesses. Unlike many towns, the main church does not face this plaza. It is set back from it about a block.[2]

The Santo Domingo church and former monastery is the largest structure in the town, set on a small hill overlooking the river.(sectorchiapas) It is locally known as the “Iglesia Grande” or Big Church.[4] The structure was built in the second half of the 16th century and attributed to Pedro de Barrientos and Juan Alonso. The church is one of the best preserved from the 16th century in Chiapas.[5] It has three naves, a coffered ceiling and cupolas above the presbytery and intersection.[5] It is based on the Moorish churches of the Seville region in Spain, but it also has Gothic, Renaissance and Neoclassical influences.[2][4] Its main bell tower has the largest bells in the country.[2] The main altar of the church is only about two decades old and made of cedar, designed in Puebla. The entire piece is supposed to be gilded but so far only a small area in the upper part has had this treatment. The gold used here is 24 carat from Italy and measures two meters by eighty centimeters. The work cost 150,000 pesos, which was collected through raffles and donations for the project. To finish the work, another half a million pesos is needed.[5] Other images in the church include an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Saint Joseph, the Archangel Michael, Saint Dominic and Saint Sebastian.[5] The church complex is partially maintained by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).[2]

To the side of the Big Church is the former Dominican monastery. This structure has been restored to house exhibition halls, including those associated with the Museo de la Laca (Lacquer Museum).[2][4] The most important craft in the municipality is the working of wood, often with these pieces glazed in lacquer. One item is the masks used for traditional dances such as Parachicos. Another is the popular musical instrument the marimba. Lacquer is used on wooden items and other things such as gourds. It is decorative, often with intricate designs. This craft is locally called “laca.”[2]

Other important churches in the town include the Calvario and the San Sebastian. The Calvario Church is from the 17th century. It was remodeled in Gothic Revival architecture at the beginning of the 19th century. Its interior conserves a wooden relief which was part of the Santo Domingo Church. San Sebastian is a church in ruins located on the San Gregorio hill. It was constructed in the 17th century when the city was at its height. It had three naves separated by archways. However, only its apse and facade remain with elements of Moorish, Renaissance and Baroque elements.[2]

The municipality Chiapa de Corzo is the local governing authority for 83 other communities, all of which are considered rural for a total territory of 906.7km2. These communities include Julián Grajales, Las Flechas, Salvador Urbina, El Palmar San Gabriel, Caleció Narcia, Ignacio Allende, Venustiano Carranza and Nicolás Bravo. ) Twenty three percent of the municipality's land is communally owned in ejidos with the rest either privately owned or parkland. The municipality borders the municipalities of Soyaló, Osumacinta, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Suchiapa, Villaflores, Zinacantán, Ixtapa, Acala and Villa Corzo. The municipality has 233.55 km of principal roadways, divided among rural roads managed by SCT, the Comisión Estatal de Campinos, the Secretaría de Obras Públicas, Desarrollo Rural, Defensa Nacional and the Comisión Nacional del Agua.[4]

Throughout the municipality, festivals, music and cuisine are similar. The Festival of the Señor de El Calvario is a social and religious event which occurs on 7 October. It honors an image of Christ with masses, popular dances, fireworks and amusement rides along with cultural and sporting events. The Fiesta Grande is celebrated from 15 to 23 January and it is the most important for the year. The marimba is the most often heard instrument at festivals and parties.[2] The main dishes include stews with potatoes and squash seeds, pork with rice and tamales.[4] Cochito is pork cooked in an adobo sauce. It is popular throughout the state but important in Chiapa de Corzo for the Comida Grande which is served during the Festival of San Sebastian in January. Another is a beef dish where the meat is dried then fried then served with a sauce made from squash seeds, green tomatoes and achiote. Typical sweets are also made with squash seeds. A typical cold drink is pozol.[2]

Historically, the dominant indigenous ethnicity has been the Zoques and there are still Zoque communities in the municipality.[2] As of 2005, there were 2,899 people who spoke an indigenous language, out of a total of over 60,000. Most of the municipality's population is young with 64% under the age of thirty and the average age of twenty one. The rate of population growth is just over three percent, which is above the state average of 2.06%. The population of the municipality is expected to double within twenty three years. Over 48% of the population lives in the city proper and the rest live in the 276 rural communities. Population density is at 67 inhabitants per square kilometers, below the regional average of 75/km2 but above the state average of 52. The average woman has 2.89 children which is below the state average of 3.47. Over 76% of the population is Catholic with about 13percent belonging to a Protestant or other Christian group. Illiteracy as of 2000 was at just under twenty percent, down from just under twenty five percent in 1990. Of those over 15 years of age, just under 25% have not completed primary school, about 17% with primary completed and over 35% having education above the primary level.[4]

According to Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO) the municipality has a high rate of socioeconomic marginalization, despite the fact that it is between the two least marginalized municipalities in the state, Tuxtla Gutiérrez and San Cristóbal. As of 2005, there were 16,327 residences. Just over 84% of homes are owned by their residents, with an average occupancy of 4.62 people per home, which is about state average. Over 28% of homes have dirt floors and about 64% have cement. About 62% of homes have cinderblock walls, and roofs are either made of tile (about 40%) and or a slab of concrete (about 30%). About 95% of homes have electricity, over 70% have running water and over 77% have sewerage, all above state average.[4]

Over 35% of the municipality's working population is in agriculture. Of these, about a third do not receive any salary for their work. Principal crops include corn, peanuts, sorghum, cotton, bananas, mangos, melons, jocote (Spondias purpurea), chard, lettuce and onions. Livestock includes cattle, pigs and domestic fowl as well as beekeeping. Fishing is limited to species such as mojarra and catfish. Just over 20% of the population is dedicated to industry, construction and transportation. The main industry is the Nestlé plant. There are also plants that manufacture plywood and bricks. There is also some handcraft workshops. Over 41% of the population is dedicated to commerce, services and tourism. One of the main tourist attractions for the municipality is the Sumidero Canyon, with the municipal docks on the Grijalva River mostly serving tour boats into the National Park up to the La Angostura Dam. Most commerce is small stores and commercial centers for local needs and some for tourism. Services include hotels, auto repair and professional services. There are three hotels with seventy nine rooms.[4]

The Fiesta Grande de Enero

The Fiesta Grande de Enero (Great January Feast) takes place from 4 to 23 January every year in Chiapa de Corzo, to honor local patron saints Our Lord of Esquipulas, Anthony the Great and Saint Sebastian. The festival has been included in UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists on November 16, 2010, listed as "Parachicos in the traditional January feast of Chiapa de Corzo".[6] Since then, the event has experienced a surge in interest, making the Dance of the Parachicos the highlight. However, this has not assured the survival of the event or of the Parachicos dancers. There are fewer dancers than in the past, and many of the younger generation are not interested in the time it takes to carve a traditional mask from wood then lacquer it.[7]

The Fiesta Grande de Enero is a celebration which joins a number of events which all happen in the month of January. Originally, these were the feast days of patron saints and other figures, including a Christ figure called the Our Lord of Esquipulas, Anthony the Great and Saint Sebastian. Since then, it has developed to include other events and overall it is meant to give thanks for what has been received over the past year.[7] On 8 January, the Fiesta Grande is announced and the first of the dances, by dancers called “Chuntas,” is performed. The feast day of the Our Lord of Esquipulas is on January 15, who is honored where he is kept at the Señor de Milagros Church. On 16 January the festival of Saint Sebastian is announced. 17 January is dedicated to San Antonio Abad with a parade of Parachicos. On 18 January, the Parachicos visit the graves of deceased patrons. On 19 January the festival of Saint Sebastian is announced. The 20th is dedicated to this saint as well, with activities starting early and foods such as pepita con tasajo to the public.[8] On the 21 of January a naval battle takes place on the Grijalva River, which consists of a spectacle using thousands of fireworks. This tradition began in 1599, when Pedro de Barrientos, vicar of the Santo Domingo Church, encouraged the development of fireworks making. He came up with the naval battle idea as a diversion and over time it became a way to fascinate visitors. Today, the battle is a recreation of the Battle of Puerto Arturo which occurred on 21 January 1906, by a group of local firework makers. On 22 January, there is a parade with floats. This day is marked with confetti and mariachis along with various types of dancers. The last day, the 23rd is marked by a parade of dancers.[8] Then there is a mass. During these last hours, the drums and flutes play a melancholy tune as the fireworks ends and the streets quiet. The Parachicos cry during their mass as the festival ends. The traditional food during this time is pork with rice and pepita con tasajo.[9]

Although the Parachicos are the best known and recognized of the dancers, there are actually three types. All refer back to a story that takes place in the colonial era. According to legend, Doña María de Angula was a rich Spanish woman who traveled in search of a cure for a mysterious paralytic illness suffered by her son, which no doctor could cure. When she arrived here, she was directed to a curandero, or local healer called a namandiyuguá. After examining the boy, he instructed his mother to bathe him in the waters of a small lake called Cumbujuya, after which he was miraculously cured.[8][9] To distract and amuse the boy, a local group disguised themselves as Spaniards with masks and began to dance showing “para el chico” which means “for the boy.” According to one version of the story, this is what cured the child.[8] The tradition of these dancers began in 1711, leading the Spanish to call the event “para el chico”, which eventually evolved into Parachicos.[9]

The term is also used to refer to the best known of the dancers of the Fiesta Grande. The Parachicos dress in a mask, a helmet or wig made of ixtle, a Saltillo style sarape. The mask is carved of wood and decorated with lacquer to mimic a Spanish face. Originally the masks had beards, but over time they evolved and many have an almost childlike look. The ixtle head covering is supposed to mimic blonde hair. The dancers carry a type of maraca made of metal called chinchin to make noise along with the taping of their boot heels. These carry a guitar and/or whip (the latter used by encomenderos in the colonial period).[7][8][9] The dancers use the whips to lightly tap children, youths, old men and even some women.[7] These dancers appear a number of times during the days of the Fiesta Grande. These processions visit the various churches on their path, which are decorated with branches, on which are hung breads, sweets, fruits and plastic decorations.[7]

Accompanying the Parachicos or dancing on their own is another type of dancer called “chuntas.” These are men dressed as women as the word chunta means maid or servant. These figures represent the “servants” of Doña María. Most of the men dress in shirts and long skirts.[9] The two types of dancers appear on several occasions during the days of the festival dancing and marching to pipes, drums and other instruments. The dance reenacts the search for relief from a pain and suffering, including hunger. The dancers distribute food and small gifts for this reason. The route is lined by spectators who hope to receive some of the gifts that the dancers distribute.[9]

The “patron” of the dances and processions has been the Nigenda family for about seventy years, whose house at 10 Alvaro Obregon Avenue becomes the meeting point for the dancers during the festival. At the back of the patio of this house, there is an altar which the portraits of two deceased members of the family Atilano Negenda and Arsenio Nigenda. The latter ceded the charge of the dance to the current patron, Guadalupe Rubicel Gomez Nigenda in 1999.[7] The Parachicos dress in their costumes at the patron's house, then they pray as a group. First the musicians exit playing flutes, drums and whistles. At a signal, the hundreds of Parachicos begin dancing and shouting. At the end of the parade is the patron, Rubisel Nigenda, who is accompanying by a “Chulita” a young woman who does not wear a mask, but rather an old fashioned traditional Chiapan dress, with a long skirt, embroidered shirt and roses. She represents the women of Chiapas. They are followed by people carrying flags representing various saints. In the middle of these is the flag of the city's patron saint and “king” of the festival, Saint Sebastian.[8]

Environment

The municipality consists of rolling hills which alternate with flat areas, mostly along rivers and streams. Most of the territory is in the Central Valley region but in the northwest, it transitions into the Central Highlands. The main rivers include the Grijalva, also called the Grande de Chiapa and the Santo Domingo. Streams include El Chiquito, Majular, Nandaburé and Nandalumí. The climate is hot and relatively humid with most rain falling from July to November. The annual average temperature in the city is 26C with an annual rainfall of 990mm.[2][4]

The natural vegetation of the area is lowland rainforest with pine-oak forests in the extreme north. However, much of these forests have been overexploited with the loss of wildlife. Wildlife includes river crocodiles, coral snakes, heloderma, iguanas, opossums and skunks. Part of the Sumidero Canyon National Park is in the municipality. The El Chorreadero is a state park located in the municipality centered on the waterfall of the same name. It has an area of 100 hectares with lowland rainforest and secondary vegetation. The Grijalva River extends twenty three km from the city to the Chicoasén Dam, formally known as the Ing. Manuel Moreno Torres, one of the largest in Latin America. Boats touring the canyon leave from the Cahuaré Docks.[4]

History

The region has been inhabited at least since the Archaic period of Mesoamerican history.[10] The immediate area of the municipality was settled around 1200 BCE by a group of people related to the Olmec culture, who are thought to have been speakers of an early Mixe–Zoquean language. However, the exact relationship between Chiapa de Corzo and the Olmec world has not been definitively established. By 900 or 800 BCE, the village, now archeological site, show a strong relationship with the Olmec center of La Venta, but it is unknown if Chiapa was ruled by La Venta or not. However, much the settlement shared many features with La Venta, including a ceremonial pond and pottery styles as well as using the same sources for materials such as obsidian and andesite.[11]

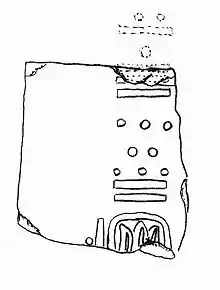

The Chiapa site is important because it shows a Mixe–Zoque–Olmec culture which eventually split from the Olmec.[11][12] The development of the ancient city has been divided into a number of phases. The earliest and most important are the Escalera or Chiapa III (700-500BCE) and Francesa or Chiapa IV (500BCE to 100CE) phase. Olmec influence is strongest in the Escalera phase when it became a planned town with formal plazas and monumental buildings. However, contacts with Mayan areas is evident as well. However, even during this phase, there are significant differences in architecture and pottery which suggest a distinct Zoque identity from the Mixe–Zoque/Olmec cultural base. The distinction grew in the Francesca period as monumental structures were enlarged and pottery was almost all locally made. There is also evidence of participation in long distance trade networks, and the first examples of hieroglyphic writing appear. The earliest Long Count inscription in Mesoamerica derives from this phase, with a date of 36 BCE appearing on Stela 2.[11] At its height, was an independent city on major trade routes. It may have been a major influence for the later Maya civilization as the pyramids in Chiapa are very similar to the E group pyramids found in most of Mesoamerica.[12] The following Horcones phase and Istmo phase to 400 CE show more elaborate tomb construction and craft specialization. By the end of these phases, however, craft activity diminishes and long distance ties contracted even though tombs remain elaborate. The final centuries are associated with the Jiquipilas phase around 400 CE. It is not known what brought down the civilization, but the city became gradually abandoned and appears to have become a pilgrimage site, perhaps by Zoque who had been conquered by the Chiapa people.[11]

Whether the Chiapa actually conquered the Zoque city or whether it had fallen before their arrival, the newcomers decided to occupy the adjacent floodplain of the Grijalva River, where the modern town is, and leave the old ruins untouched. By the early 16th century, this town had become a local power center called Napinaica.[3][11] The Chiapa people were distinct from others in Chiapas in size, nudity, and fierceness which impressed the Spanish who noted it in their writings.[3] These people were fiercely opposed to Spanish intrusion and were a major obstacle to the first efforts by the conquistadors to dominate. However, in 1528, Diego de Mazariegos succeeded in breaking this resistance by enlisting the help of neighboring peoples who were enemies of the Chiapa. The last Chiapa leader, named Sanguieme, tried to help his people escape the domination of the Spanish but, according to historian Jean de Vos, he was captured and burned alive in a hammock strung between two kapok trees, with a hundred of his followers hung from trees near the river.[3]

After the conquest, the town was refounded with the name of Villa Real de Chiapa by a large kapok tree called La Pochota as the first European city in Chiapas.[2][3][4] However, the hot climate of the area did not entice many Spanish to stay. Most instead went to the northeast into the cooler mountains to found another city, today San Cristobal. The mountain city would be founded as Chiapa de los Españoles, while Villa Real de Chiapa would become known Chiapa de los Indios, left to the indigenous and monks there to evangelize them.[3] Despite this, the city would remain one of the most important for the first 200 years of colonization.[2] While it was an encomienda at first, it became a dependency of the Spanish Crown in 1552, changing its name to Pueblo de la Real Corona de Chiapa de Indios.[2] The developers of the area were Dominican friars, who followed the ideals of Bartolomé de las Casas in neighboring San Cristobal. They worked to protect the indigenous against the abuses of the Spanish colonizers, allowing them to gain the trust of the local people and convert them to Christianity. They also taught the local indigenous crafts such as European pottery methods, fireworks making and rope making. The Dominicans also built many of the landmarks of the town such as the La Pila fountain. This protection and the very high percentage of indigenous population in the colonial period allowed for many indigenous names to survive to the present day. Along with surnames such as Grajales, Castellanos, Marino Hernández, there is Nandayapa, Tawa, Nuriulú, Nampulá and Nangusé among others.[3]

In 1849, the city was declared the seat of its district. The town was officially declared a city in 1851. “de Corzo” was added to the name in 1881 in honor of Liberal politician Angel Albino Corzo. In 1863, there was a battle between the French and the Liberals, with the latter led by Salvador Urbina.[4]

Between 1970 and 1979, the construction of the Chicoasén Dam caused earthquakes in the area. One of these toppled the large bell in the main church.[4] The main highway that connects the city with San Cristóbal was built in 2000. During this same year, the first non PRI municipal president was elected, from the National Action Party.[4]

Archeology

While there is evidence of human occupation in the region from at least the Archaic period the main archeological site for the area is near the modern town of Chiapa de Corzo. This archeological site is located 2 kilometers away from Grijalva River. The origin of this ceremonial and administrative center goes back 3,500 years, being a strategic point in commercial routes between the Pacific and Gulf of Mexico coasts.[13] It was one of the largest settlements in early Mesoamerica occupied from 1200 BCE to 600 CE.[11] This site had been occupied from at least 1400 BCE until sometime in the late Classic period. The site reached its height between 700 BCE to 200 CE, when it was a large settlement along major trade routes.[12][14]

The site is important for a number of reasons. First, while it was definitely inhabited by Mixe-Zoque speakers, it has strong ties to the Olmecs, but it is not known what exactly these ties were. Some theories state that the population was genetically related to the Olmecs, while others suppose that they were dominated by the Olmecs initially but then eventually broke away.[12] There have been significant finds here such as the oldest Mesoamerican Long Count calendar with the date of 36 BCE on a monument, as well as a pottery shard with the oldest instance of writing system yet discovered.[15]

A recent discovery has been the oldest pre Hispanic tomb, dated to between 700 and 500 BCE. It was found in a previously excavated 20-meter-tall pyramid, but in the very center. The occupant is richly attired with more than twenty axes found as offerings, placed in the cardinal directions. The culture is considered to be Olmec although more exact dating needs to be done. The offerings show Olmec influence, such as depictions of wide eyes and lips, but other typical Olmec decorations such as earspools and breastplates are missing. In addition to the axes, there are also more than three thousand pieces made of jade, river pearls, obsidian and amber, from areas as far away as Guatemala and the Valley of Mexico, showing trade networks. The face was covered in a seashell with eye and mouth openings, the earliest example of a funeral mask.[12][16][17] The burial shows that many elements of Mesoamerican burials are older than previously thought.[17]

The archeological site lies just outside the urban sprawl of modern Chiapa de Corzo, but the city is growing over it and many areas known to contains ruins underground are encroached upon by modern homes and businesses. The discovery of the ancient tomb has prompted the Mexican government to buy more lands and extend the site by 7,200 square meters to one and a half hectares. Part of the site has been open to tourism since late 2009.[11][18]

References

- "Chiapa de Corzo". Catálogo de Localidades. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social (SEDESOL). Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- "Chiapa de Corzo" (in Spanish). Chiapas, Mexico: Secretaría de Turismo de Chiapas. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "La antigua Napiniaca. La historia de Chiapa de Corzo" [Ancient Napiniaca: The history of Chiapa de Corzo] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconocido magazine. November–December 1997. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Chiapa de Corzo". Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Estado de Chiapas (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal and Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas. 2005. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Mariana Morales (April 11, 2011). "Bañan en oro una del templo de Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas" [One bathes in gold at the church in Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas]. El Heraldo de Chiapas (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ICH entry. Unesco.org (2009-12-11). Retrieved on 2011-06-03.

- "Tradición de "Los parachicos" de Chiapa de Corzo, vive tiempos de auge y desafío" [The Los Parachicos tradition of Chiapa de Corzo, experiencing times of growth and challenge]. TV Azteca 21 (in Spanish). Mexico. January 21, 2011. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "La fiesta grande de Chiapa de Corzo" [The Fiesta Grande of Chiapa de Corzo]. El Informador (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. November 29, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Fiesta Grande de Chiapa de Corzo" (in Spanish). Chiapa de Corzo, Mexico: Municipality of Chiapa de Corzo. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Lowe, p. 122-123.

- "Chiapa de Corzo Archaeological Project". Brigham Young University. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- John Roach (May 18, 2010). "Pyramid Tomb Found: Sign of a Civilization's Birth?". National Geographic News. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Villarreal, Ignacio. "Zoque Culture Archaeological Site Inaugurated at Chiapa de Corzo". Artdaily.com. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Lowe, pp. 122–123.

- Justeson, p. 2.

- Leticia Sánchez (April 13, 2010). "La tumba prehispánica más antigua, en Chiapas" [The oldest pre Hispanic tomb in Chiapas]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- Ana Mónica Rodríguez (May 18, 2010). "Chiapa de Corzo: hallan milenario entierro múltiple" [Chiapa de Corzo:Found multiple thousand year old burial]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 8. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Amplian Chiapa de Corzo su área arqueológica y de investigación" [Expanding Chiapa de Corzo’s archeological and research area] (Press release) (in Spanish). Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. April 5, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

Bibliography

- Justeson, John S., and Kaufman, Terrence (2001) Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing and Texts.

- Lowe, G. W., "Chiapas de Corzo", in Evans, Susan, ed., (2009) Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America, Taylor & Francis, London. ISBN 0-415-87399-1