Chicomecōātl

In Aztec mythology, Chicomecōātl [t͡ʃikomeˈkoːaːt͡ɬ] "Seven Serpent", was the Aztec goddess of agriculture during the Middle Culture period.[1] She is sometimes called "goddess of nourishment", a goddess of plenty and the female aspect of maize.[2]

More generally, Chicomecōātl can be described as a deity of food, drink, and human livelihood.[3]

She is regarded as the female counterpart of the maize god Centeōtl, their symbol being an ear of corn. She is occasionally called Xilonen,[4] (meaning doll made of corn), who was married also to Tezcatlipoca.[5]

Significance of Name

Chicomecōātl's name, "Seven Serpent", is thought to be a reference to the duality of the deity. While she symbolizes the gathering of maize and agricultural prosperity, she also is thought to be harmful to the Aztecs, as she was thought to be of blame during years of poor harvest.[6]

Appearance & Depiction

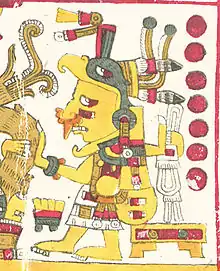

Her appearance is mostly represented with red ochre on the face, paper headdress on top, water-flowers patterned shirt, and foam sandals on the bottom. She is also described as carrying a sun flower shield.[3]

She is also often appeared with attributes of Chalchiuhtlicue, such as her headdress and the short lines rubbing down her cheeks. Chicomecōātl is usually distinguished by being shown carrying ears of maize.[2] She is shown in three different forms:

- As a young girl carrying flowers

- As a woman who brings death with her embraces

- As a mother who uses the sun as a shield[2]

Chicomecōātl, as depicted in Codex Magliabechiano

Chicomecōātl, as depicted in Codex Magliabechiano.jpg.webp) Relief with Maize Goddess (Chicomecóatl), Stone, Aztec.

Relief with Maize Goddess (Chicomecóatl), Stone, Aztec._MET_DT5110.jpg.webp) Maize Deity (Chicomecoatl), basalt

Maize Deity (Chicomecoatl), basalt.jpg.webp) (Museo Nacional de Antropologia)

(Museo Nacional de Antropologia)

Festivals

She is particularly recognized during Huey Tozoztli, the first of sequence of three festivals held in high season marking the harvest. During the festival, her priestesses designate seed corn that is to be planted in the coming season. To appease the deity, as well as to ask for good harvest, priests often engaged in child sacrifice.[6] Dried seed maize, harvested and retained for the following year, bore the title Chicomecōātl, while maize consumed following harvest season was generally referred to as Cinteotl.[7]

See also

- Centeōtl (Aztec god of maize)

- Maya maize god

- Xilonen god

References

- Aguilar-Moreno, Manuel (2006). Handbook to life in the Aztec world. New York, NY: Facts on File. pp. 197–8. ISBN 978-0816056736.

- Gregg, Susan (2011-03-01). The encyclopedia of angels : spirit guides & ascended masters : a guide to 200 celestial beings to help, heal, and assist you in everyday life. Beverly, Mass.: Fair Winds Press. p. 239. ISBN 9781592334667.

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain (Translation of and Introduction to Historia General de Las Cosas de La Nueva España; 12 Volumes in 13 Books ), trans. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O Anderson (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1950-1982), p.4

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000). Encyclopedia of ancient deities. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786403172.

- Coulter, Charles Russell; Turner, Patricia (2000). Encyclopedia of ancient deities. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. p. 508. ISBN 978-0786403172.

- Durán, Diego (1971). Book of the gods and rites and the ancient calendar (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806108896. OCLC 149976.

- F., Townsend, Richard (2009). The Aztecs (3rd ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500287910. OCLC 286447216.

- "Maize Deity (Chicomecoatl)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 September 2008.