Chihuahuan Desert

The Chihuahuan Desert (Spanish: Desierto de Chihuahua, Desierto Chihuahuense) is a desert and ecoregion designation covering parts of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. It occupies much of West Texas, the middle and lower Rio Grande Valley, the lower Pecos Valley in New Mexico, and a portion of southeastern Arizona, as well as the central and northern portions of the Mexican Plateau. It is bordered on the west by the Sonoran Desert and the extensive Sierra Madre Occidental range, along with northwestern lowlands of the Sierra Madre Oriental range. On the Mexican side, it covers a large portion of the state of Chihuahua, along with portions of Coahuila, north-eastern Durango, the extreme northern part of Zacatecas, and small western portions of Nuevo León. With an area of about 501,896 km2 (193,783 sq mi),[1] it is the largest desert in North America.[2]

| Chihuahuan Desert | |

|---|---|

Chihuahuan desert landscape in Big Bend National Park | |

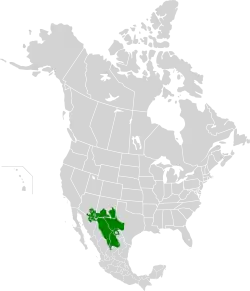

Location map of Chihuahuan Desert | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Deserts and xeric shrublands |

| Borders | |

| Geography | |

| Area | 501,896 km2 (193,783 sq mi) |

| Countries | Mexico and United States |

| States | |

| Coordinates | 30°32′26″N 103°50′14″W |

| Rivers | Rio Grande |

| Conservation | |

| Conservation status | Vulnerable |

| Global 200 | Yes |

| Protected | 35,905 km2 (13,863 sq mi) (7%)[1] |

Geography

Several larger mountain ranges include the Sierra Madre, the Sierra del Carmen, the Organ Mountains, the Franklin Mountains, the Sacramento Mountains, the Chisos Mountains, the Guadalupe Mountains, and the Davis Mountains. These create "sky islands" of cooler, wetter, climates adjacent to, or within the desert, and such elevated areas have both coniferous and broadleaf woodlands, including forests along drainages and favored exposures. The lower elevations of the Sandia–Manzano Mountains, the Magdalena–San Mateo Mountains, and the Gila Region partly border the Chihuahuan Desert and partly border other ecoregions that are not deserts.

There are a few urban areas within the desert: the largest is Ciudad Juárez with almost two million inhabitants; Chihuahua, Saltillo, and Torreón; and the US cities of El Paso and Albuquerque. Alamogordo, Alpine, Benson, Carlsbad, Carrizozo, Deming, Fort Stockton, Fort Sumner, Las Cruces, Marfa, Pecos, Roswell, and Willcox are among the other communities in this ecoregion.

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature the Chihuahuan Desert may be the most biologically diverse desert in the world as measured by species richness or endemism. The region has been badly degraded, mainly due to grazing.[3] Many native grasses and other species have become dominated by woody native plants, including creosote bush and mesquite, due to overgrazing and other urbanization. The Mexican wolf, once abundant, was nearly extinct and remains on the endangered species list.[4]

Climate

The desert is mainly a rain shadow desert because the two main mountain ranges covering the desert, the Sierra Madre Occidental to the west and the Sierra Madre Oriental to the east block most moisture from the Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, respectively.[5] Climatically, the desert mostly has an arid, mesothermal climate with one rainy season in the late summer and smaller amounts of precipitation in early winter, the mean daily temperature of the coldest month warmer than 0 °C (32 °F).[5] The majority of rain falls between late June and early October, during the North American Monsoon when moist air from the Gulf of Mexico penetrates into the region, or much less frequently, when a tropical cyclone moves inland and stalls.[5][6] Owing to its inland position and higher elevation than the Sonoran Desert to the west, mostly varying from 480 to 1,800 m (1,575 to 5,906 ft) in altitude,[7] the desert has a slightly milder climate in the summer (though usually daytime June temperatures are in the range of 32 to 40 °C or 90 to 104 °F), with mild to cool winters and occasional to frequent freezes.[6] The average annual temperature in the desert varies from about 13 to 22 °C (55 to 72 °F), depending on elevation and latitude. The hottest temperatures in the desert occur in lower elevation areas and valleys, including near the Rio Grande from south of El Paso into the Big Bend, and the Bolson de Mapimi.[7] Northern and eastern portions have more definite winters than southern and western portions, receiving a portion of winter precipitation as snowfall most winters.[6] The mean annual precipitation for the Chihuahuan Desert is 235 mm (9.3 in) with a range of approximately 150–400 mm (6–16 in), although it receives more precipitation than most other warm desert ecoregions.[5] Nearly two-thirds of the arid zone stations have annual totals between 225 and 275 mm (8.9 and 10.8 in).[8] Snowfall is scant except at the higher elevation edges. The desert is fairly young, existing for only 8000 years.[5]

Flora

The creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) is the dominant plant species on gravelly and occasional sandy soils in valley areas within the Chihuahuan Desert. The other species creosote bush is found with depend on factors including the soil type, elevation, and degree of slope. Viscid acacia (Vachellia vernicosa), and tarbush (Flourensia cernua) dominate northern portions, while broom dalea (Psorothamnus scoparius) occurs on sandy soils in western portions. Yucca and Opuntia species are abundant on slopes and uplands in most areas, while Arizona rainbow cactus (Echinocereus polyacanthus) and Mexican fire-barrel cactus (Ferocactus pilosus) inhabit portions near the US–Mexico border.

Herbaceous plants, such as bush muhly (Muhlenbergia porteri), blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), gypsum grama (B. breviseta), and hairy grama (B. hirsuta), are dominant in desert grasslands and near the mountain edges including the Sierra Madre Occidental. Lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla), honey mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa), Opuntia macrocentra and Echinocereus pectinatus are the dominant species in western Coahuila. Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens), lechuguilla, and Yucca filifera are the most common species in the southeastern part of the desert. Candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica), Mimosa zygophylla, Acacia glandulifera and lechuguilla are found in areas with well-draining, shallow soils. The shrubs found near the Sierra Madre Oriental are exclusively lechuguilla, guapilla (Hechtia glomerata), Queen Victoria's agave (Agave victoriae-reginae), sotol (Dasylirion spp.), and barreta (Helietta parvifolia), while the well-developed herbaceous layer includes grasses, legumes and cacti.

Desert or arid grasslands comprise 20% of this desert and are often mosaics of shrubs and grasses. They include purple three-awn (Aristida purpurea), black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda), and sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula). Early Spanish explorers reported encountering grasses that were "belly high to a horse;" most likely these were big alkali sacaton (Sporobolus wrightii) and tobosa (Pleuraphis mutica) along floodplain or bottomland areas.[3]

Protected areas

A 2017 assessment found that 35,905 km2 (13,863 sq mi), or 7%, of the ecoregion is in protected areas.[1] Protected areas include Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge in Arizona, Médanos de Samalayuca Natural Protected Area and Cañón de Santa Elena Flora and Fauna Protection Area in Chihuahua, Cuatro Ciénegas Basin, Ocampo Flora and Fauna Protection Area, and part of Maderas del Carmen Biosphere Reserve in Coahuila, Mapimí Biosphere Reserve and Cañón de Fernández State Park in Durango, Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, Carrizozo Malpais, Oliver Lee State Park, Organ Mountains–Desert Peaks National Monument, Petroglyph National Monument, Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge, and White Sands National Park in New Mexico, and Big Bend National Park, Big Bend Ranch State Park, Black Gap Wildlife Management Area, Franklin Mountains State Park, and part of Guadalupe Mountains National Park in Texas.

Gallery

Young creosote bush (Larrea tridentata)

Young creosote bush (Larrea tridentata)

Lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla)—one of the indicator plants of the Chihuahuan Desert

Lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla)—one of the indicator plants of the Chihuahuan Desert Poza Azul, one of many a springs in the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin in central Coahuila, Mexico (2009).

Poza Azul, one of many a springs in the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin in central Coahuila, Mexico (2009).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chihuahuan Desert. |

References

- Eric Dinerstein, David Olson, et al. (2017). An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 6, June 2017, Pages 534–545; Supplemental material 2 table S1b.

- Wright, John W., ed. (2006). The New York Times Almanac (2007 ed.). New York, New York: Penguin Books. pp. 456. ISBN 0-14-303820-6.

- "Chihuahuan desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- "Lobos of the Southwest". Mexican Wolves. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "The Chihuahuan Desert". New Mexico State University. Archived from the original on December 27, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- "Chihuahuan Desert". National Park Service. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- "Chihuahuan Desert". Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- Chihuahuan Climate Archived September 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute

External links

- "Chihuahuan desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Chihuahuan Desert images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu (slow modem version)

- Pronatura Noreste in the Chihuahuan Desert

- Small desert beetle found to engineer ecosystems EurekAlert! March 27, 2008