Choctaw Trail of Tears

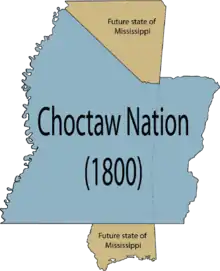

The Choctaw Trail of Tears was the attempted ethnic cleansing and relocation by the United States government of the Choctaw Nation from their country, referred to now as the Deep South (Alabama, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana), to lands west of the Mississippi River in Indian Territory in the 1830s by the United States government. A Choctaw miko (chief) was quoted by the Arkansas Gazette as saying that the removal was a "trail of tears and death." Since removal, the Choctaw have developed since the 20th century as three federally recognized tribes: the largest, the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma; the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, and the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians in Louisiana.

| Choctaw Trail of Tears | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Trail of Tears | |

| Location | United States |

| Date | 1831-1833 |

| Target | Choctaw people |

Attack type | Population transfer, Ethnic cleansing |

| Deaths | 2,500 |

| Perpetrators | United States |

| Motive | Expansionism |

Overview

After ceding nearly 11,000,000 acres (45,000 km2), the Choctaw emigrated in three stages: the first in the fall of 1831, the second in 1832, and the last in 1833.[1] The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was ratified by the U.S. Senate on February 25, 1830, and the U.S. President Andrew Jackson was anxious to make the Choctaw project a model of removal.[1]

George W. Harkins (Choctaw) wrote a letter to the American people before the removals began.

We go forth sorrowful, knowing that wrong has been done. Will you extend to us your sympathizing regards until all traces of disagreeable oppositions are obliterated, and we again shall have confidence in the professions of our white brethren. Here is the land of our progenitors, and here are their bones; they left them as a sacred deposit, and we have been compelled to venerate its trust; it dear to us, yet we cannot stay, my people is dear to me, with them I must go. Could I stay and forget them and leave them to struggle alone, unaided, unfriended, and forgotten, by our great father? I should then be unworthy the name of a Choctaw, and be a disgrace to my blood. I must go with them; my destiny is cast among the Choctaw people. If they suffer, so will I; if they prosper, then will I rejoice. Let me again ask you to regard us with feelings of kindness.

— George W. Harkins, George W. Harkins to the American People[2]

The people in the first wave of removal suffered the most. The second and third wave "sowed their fields promptly and experienced fewer hardships than the Indians of most of the other expatriated tribes."[3] Removal continued throughout the 19th century. In 1846 1,000 Choctaw removed, and by 1930 only 1,665 remained in Mississippi.[3]

Treaties

The Choctaw and the United States agreed to nine treaties between 1786 and 1830. The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was the last to be signed by which the Choctaw Nation agreed to ceding the last of their lands in the Southeast. Choctaw land was systematically obtained by European governments and the US through treaties, legislation, and threats of warfare. The Choctaw had made treaties with Great Britain, France, and Spain, before nine with the United States. Some treaties, like the Treaty of San Lorenzo, indirectly affected the Choctaw.

The Choctaw considered European laws and diplomacy foreign and puzzling. They found the writing of agreements to be the most confusing aspect of treaty making, as they had no system of written language. As with many Native Americans, the Choctaw transmitted their history orally from generation to generation. During treaty negotiations the three main Choctaw tribal areas (Upper Towns, Six town, and Lower Towns) had a "Miko" (chief) to represent them. During the Treaty of Natchez, 1793, the Upper Town Chief was last name King according to curated (verified genealogist research), the Chief of Six Towns was Pushmataha, and the Chief of Western Division was James King, Jr (Frenchimastvbe') representing the Royal Governor Carondolet.[5] Spain made the earliest claims to Choctaw country, followed by French claims starting in the late 17th century. Following the Treaty of San Lorenzo, the new United States laid claim to Choctaw country starting in 1795.

The Choctaw signed the Treaty of Hopewell in 1786. Although it did not cede any land to the United States, this treaty was important because Article 9 gave the United States Congress the right to regulate, trade, and "manage all their affairs in such a manner as they think proper".[6]

The Treaty of Fort Adams was signed to cede the land at the mouth of the Yazoo River. The Choctaw believed that ceding over 2 million acres to the United States would be enough to satisfy the American need for land, but it was not. Six months later General Wilkinson came back asking for more land and a new treaty.[7]

The Treaty of Mount Dexter was signed in November 1805, and under it the Choctaw ceded more land than by any of the previous treaties. During this time, the plan of the Jefferson administration was to force the Choctaw into debt through trading, and then allow them to pay that debt back with their land. In the case of the Mount Dexter Treaty, the Choctaw received $48,000 for the 4.1 million acres of land that they were giving up.[8] With this money, they had to pay back $51,000 to the trading houses they used.[8]

The Treaty of Doak's Stand was considered one of Andrew Jackson's greatest achievements since the Battle of New Orleans. It , and one of the first "significant achievement of Calhoun's policy of moderation."[9] The treaty had the Choctaws ceding five million acres of land, but they were to receive thirteen million acres of land in Arkansas.[10] This treaty foreshadows the removal and degradation of all Indians.[11] This became problematic because the people in Arkansas felt as though their government had abandoned them in order to remove the Indians from Mississippi, so they began launching an all-out effort to prevent the treaty from being ratified.[12] Although the treaty was ratified, President Jackson appointed a surveyor to find another border line that would give the Choctaws the same amount of land without upsetting the status quo of the whites.[13]

Although many leaders of the Choctaw tribe were opposed to the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, Grant Foreman in 1953 wrote that "most of the leaders had been aligned securely by bribery with the government and the treaty."[14] Greenwood LeFlore, Nitakechi (William Ambrose), Mushulatubbe, and more than 50 other "favored members" gained land by signing the treaty.[15] According to Foreman, LeFlore had a personal interest in removing the tribes, as he boasted to President Jackson about his ability to remove them even if the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was not ratified.[16] Before the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek had been ratified, the government allowed LeFlore to send numerous unorganized and ill-provisioned tribe members to the west in the first wave of removal.[16] Of the one thousand Choctaw emigrants sent west by Leflore, Foreman said that only eighty-eight arrived.[17] Since then, other historians have suggested that some Choctaw favored removal because they pragmatically wanted to try to get the best deal from a US that seemed implacably intent on forcing them out.

American pressure to force the Choctaw to cede their land continued until the Choctaw fought as their allies against the Creek in the Creek War of 1813. This was in part a civil war within the nation that broke out while the US was engaged against Great Britain in the War of 1812. e MS Band of Choctaw chose to stay in Mississippi and not remove, partly due to the Nation of Choctaw Chief being Brig. General Pushmataha and the respect for his service from the age of 13 in siding with the French of New France. As many Choctaw fought in the Battle of 1812, some Americans began to view them as allies. They were treated better by white settlers and by the natives from Dimery Settlement who entered into Ft Adams after having served in the lands of the Southern Tuscarora.[18]</ref> Colbert Research (2017)</ref>. When the Choctaw signed the treaty of Fort St. Stephens, they believed they were at "a friendly banquet [rather than] a meeting of opposing forces".[18] In exchange for the land, the Choctaw received a $6,000 annuity for the next 20 years, and goods such as guns, blankets, and tools for an additional value of $10,000.[18]

| Treaty | Year | Ceded Land |

| Hopewell | 1786 | n/a |

| Fort Adams | 1801 | 2,641,920 acres (10,691.5 km2) |

| Fort Confederation | 1802 | 10,000 acres (40 km2) |

| Hoe Buckintoopa | 1803 | 853,760 acres (3,455.0 km2) |

| Mount Dexter | 1805 | 4,142,720 acres (16,765.0 km2) |

| Fort St. Stephens | 1816 | 10,000 acres (40 km2) |

| Doak's Stand | 1820 | 5,169,788 acres (20,921.39 km2) |

| Washington City | 1825 | 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) |

| Dancing Rabbit Creek | 1830 | 10,523,130 acres (42,585.6 km2) |

Aftermath

Nearly 15,000 Choctaws together with 1000 slaves made the move to what would be called Indian Territory and then later Oklahoma.[19][20] The population transfer occurred in three migrations during the 1831–33 period including the devastating winter blizzard of 1830–31 and the cholera epidemic of 1832.[20] About 2,500 died along the trail of tears. Approximately 5,000–6,000 Choctaws remained in Mississippi in 1831 after the initial removal efforts.[21][22] For the next ten years they were objects of increasing legal conflict, harassment, and intimidation.

The Choctaw remaining in Mississippi described their situation in 1849, "we have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died."[22] Racism was rampant. Joseph B. Cobb, who moved to Mississippi from Georgia, described the Choctaw as having "no nobility or virtue at all, and in some respect he found blacks, especially native Africans, more interesting and admirable, the red man's superior in every way. The Choctaw and Chickasaw, the tribes he knew best, were beneath contempt, that is, even worse than black slaves."[23] The removals continued well into the early 20th century. In 1903, three hundred Mississippi Choctaws were persuaded to move to the Nation in Oklahoma.[24]

See also

- Trail of Tears

- Choctaw

- List of Choctaw Treaties

- Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

- Perry Cohea

Notes

- Remini, Robert (1998) [1977]. ""Brothers, Listen ...". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 273.

- Harkins, George (1831). "1831 – December – George W. Harkins to the American People". Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- Swanton, John (1931). "Choctaw Social and Ceremonial Life". Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. The University of Alabama Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8173-1109-4.

- Schreier, Jesse T. (2011). "Indian or Freedman?". Western Historical Quarterly. 42 (4): 458–479. doi:10.2307/westhistquar.42.4.0459. JSTOR westhistquar.42.4.0459.

- Guerin, Guerin. Indians (before 1970). Spain in the American Colonial Period, #124. Tulane Univ.& Hancock, MS Historical Society. p. 56.

- DeRosier, Arthur H. (1970). The Removal of the Choctaw Indians. The University of Tennessee Press Knoxville. p. 18.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 30.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 32.

- DeRosier (1970), pp. 67-68.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 65.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 69.

- DeRosier (1970), pp. 70-71.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 74.

- Foreman, Grant (1953). Indian Removal. Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press. p. 29.

- Foreman, Grant (1953). Indian Removal. Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 27–28.

- Foreman, Grant (1953). Indian Removal. Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press. p. 38.

- Foreman, Grant (1953). Indian Removal. Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42.

- DeRosier (1970), p. 37.

- Satz, Ronald (1986). "The Mississippi Choctaw: From the Removal Treaty of the Federal Agency". In Samuel J. Wells and Roseanna Tuby (ed.). After Removal: The Choctaw in Mississippi. University Press of Mississippi. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-87805-289-9.

- Sandra Faiman-Silva (1997). Choctaws at the Crossroads. University of Nebraska Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8032-6902-6.

- Baird, David (1973). "The Choctaws Meet the Americans, 1783 to 1843". The Choctaw People. United States: Indian Tribal Series. p. 36. LCCN 73-80708.

- Walter, Williams (1979). "Three Efforts at Development among the Choctaws of Mississippi". Southeastern Indians: Since the Removal Era. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- Hudson, Charles (1971). "The Ante-Bellum Elite". Red, White, and Black; Symposium on Indians in the Old South. University of Georgia Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8203-0308-6.

- Ferguson, Bob; Leigh Marshall (1997). "Chronology". Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-23.